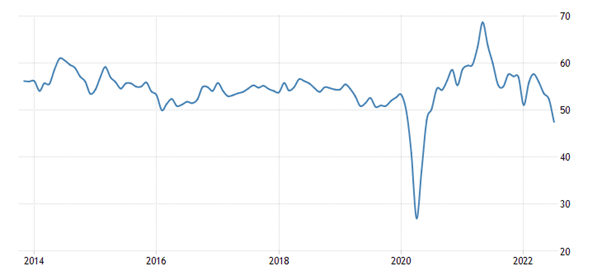

The major economies are moving closer to recession, if they are not already there; and yet inflation rates continue to rise (for now). The latest surveys of business activity, called Purchasing Managers Indexes (PMIs), show that both the Euro area and the US are now in contraction territory (i.e. any level below 50). The composite PMIs (which put together both manufacturing and services) for the major economies in July show:

US 47.5 (contraction)

Eurozone 49.4 (contraction)

Japan 50.6 (slowing expansion)

Germany 48.0 (contraction)

UK 52.8 (slowing expansion)

Nobody should be surprised by the Eurozone score, given the impact of sanctions on Russian energy imports, which is severely weakening industrial production in the core of Europe (see below). Germany’s industrial production has been contracting for over three months.

The big shock was in the US. The US composite PMI also fell into contraction territory at 47.5 in July, down sharply from 52.3 in June to signal a solid fall in private sector output. The rate of decline was the sharpest since the initial stages of the pandemic in May 2020, as both manufacturers and service providers reported subdued demand conditions. So just as we enter the second half of 2022, US business activity is diving.

And according to the latest estimate of real GDP growth by the Atlanta Federal Reserve Bank GDP NOW model, in the three months to June, the US economy contracted at a -1.6% annualized rate, matching a similar fall of -1.6% in the first quarter. If this estimate is confirmed next week, it would mean that the US was technically in recession.

The current response to this claim is: how can the US economy be in recession or close to it, when the unemployment rate is near all-time lows and payrolls keep on rising? But this response is dubious to say the least. First, there are two measures of employment for the US: the payroll figures and the household survey (a survey of households with jobs). The latter is currently showing the opposite of the former, namely a fall in the number of Americans at work. On this household measure, the labor force shrank, declining from 164.376 million to 164.023 million, and the participation rate (those in work compared to the total working age population) dropped more than expected to 62.2% – graph below.

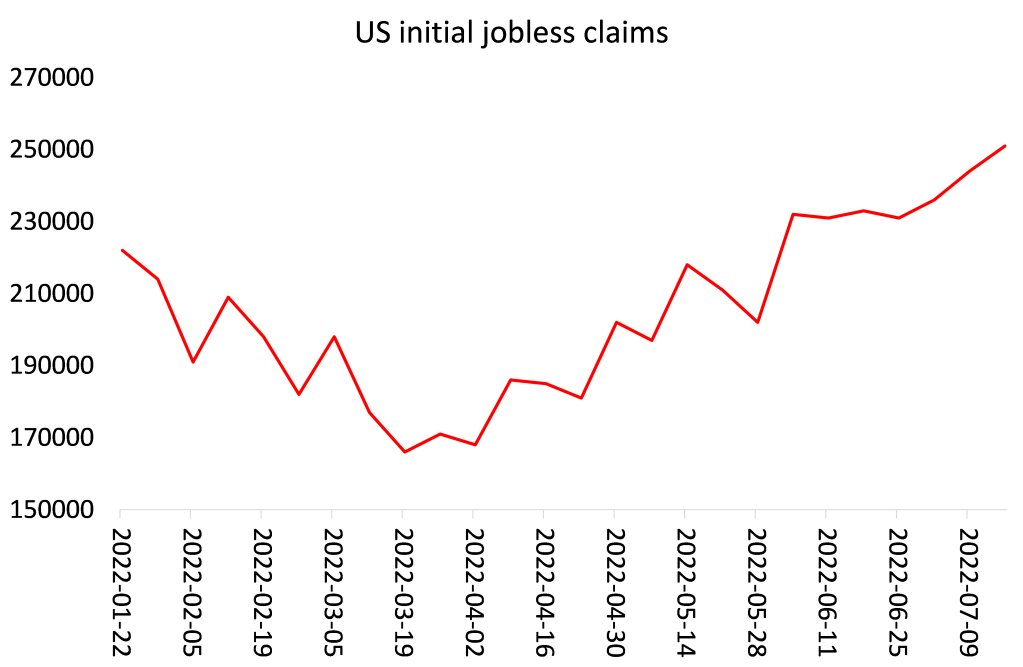

Also, the initial jobless claims (the number of people claiming benefits because they are out of work) are now on a steady rise.

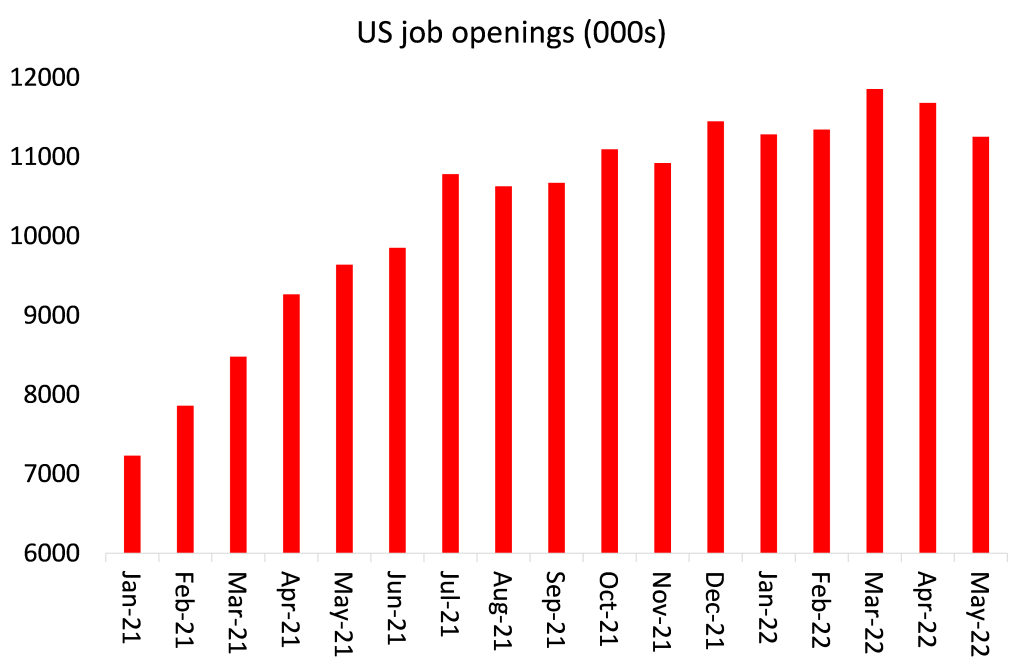

And the number of new jobs available (called JOLTS) have peaked.

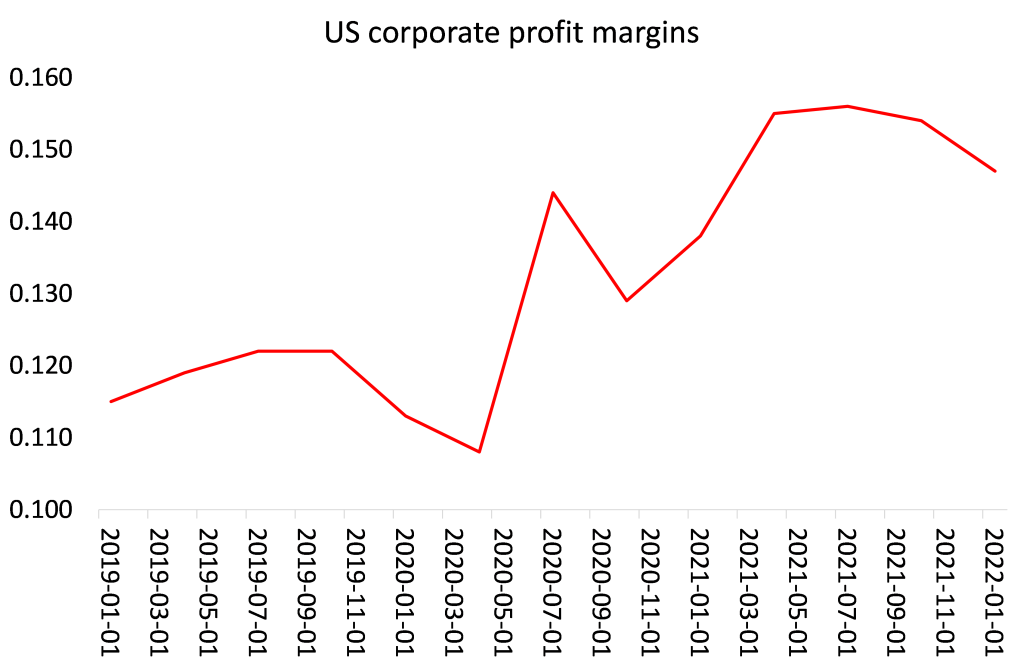

Second, and most important, unemployment is a lagging indicator in a recession. The leading indicator is the movement in corporate profits and business investment, followed by production and then unemployment. Employment comes last because it rises only when corporations stop taking on more labour and begin to reduce their workforce. And they only do this when profitability and production start to fall away. And, after reaching all-time highs, profit margins have begun to fall.

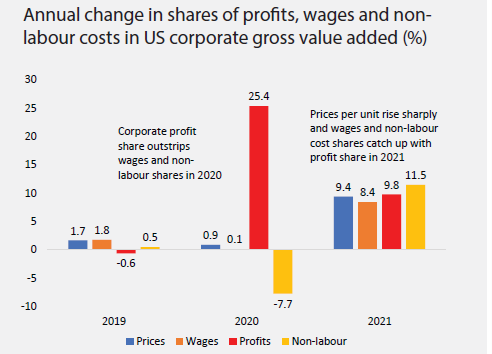

During the COVID slump, profits rose sharply compared to wages and acted as the driver and gainer in rising inflation. Now that is beginning to change as profits are squeezed by rising components costs and weakening demand.

But it is in Europe that the evidence for an outright slump is most convincing. And it’s not just the data on economic growth that support that. In addition, Europe faces a huge squeeze on energy production and imports as the sanctions being applied on Russian gas and oil imports will not be sufficiently compensated for by imports from elsewhere.

Many German manufacturers are warning that they will have to close down production completely if energy inputs dry up. Petr Cingr, the chief executive of Germany’s largest ammonia producing company, and a key supplier of fertilisers and exhaust fluids for diesel engines, warned of the devastating consequences of the ending of Russian gas supplies. “We have to stop [production] immediately,” he said, “from 100 to zero.” According to UBS analysts, no gas for the winter will result in a “deep recession” with GDP contracting 6 percent by the end of next year. Germany’s Bundesbank has warned that the effects on global supply chains of any Russian cut-off would increase the original shock effect by two and a half times. ThyssenKrupp, Germany’s largest steelmaker, has said that without natural gas to run its furnaces “shutdowns and technical damage to our facilities cannot be ruled out.”

And it’s worse. Inflation is still rising in most European economies. So the European Central Bank (ECB) has decided that it must act to raise interest rates sharply. It pushed up its policy rate by 50bp last week, more than expected, taking the rate into positive territory for the first time in a decade. The days of ‘quantitative easing’ have been replaced by ‘quantitative tightening’.

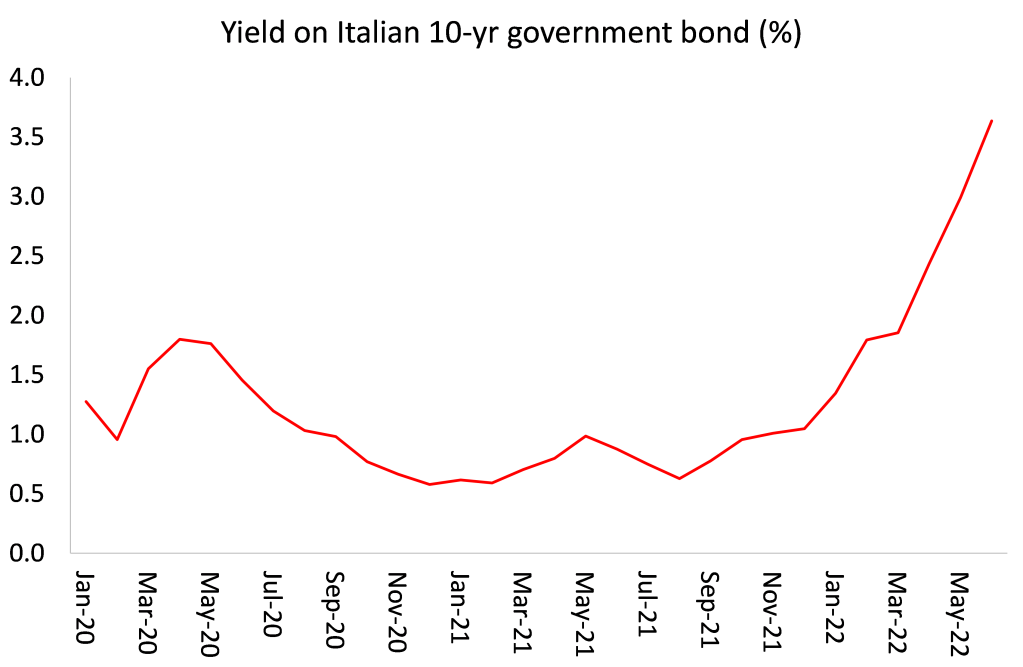

But this move comes at the worst time for countries like Italy, highly dependent on Russian energy. Last week, the technocrat former ECB chair, Italian prime minister Mario Draghi was forced to resign when several parties in his coalition government withdrew their support; some because they opposed his support for military aid to Ukraine; and some because they saw their chance to win an election. Italy has a very large public debt ratio to its GDP.

Up to now, the interest costs of servicing that debt have been low because interest rates have been kept low by the ECB, which has also provided billions of credit to Eurozone governments. But now interest rates are on the rise and investors in Italian government bonds have become worried that Italy (especially one without a viable government) may find it difficult to service these debts. So the yield on the Italian 10-year bonds surged to above 3.5%. The fall of the Italian government also threatens the distribution of billions of euros from EU Covid recovery funds, supposedly going to Italy next year to boost its economic growth.

So Europe’s economy is going down just as the ECB hikes rates to control inflation. As I have explained in previous posts, raising interest rates to control rising inflation caused by weak supply and productivity and the Ukraine war will not work, except to provoke a slump.

The ECB has now resorted to a desperate measure in introducing a transmission protection instrument (TPI), a new form of credit that will be doled out to governments like Italy if their bond prices collapse. However, this may never be used because it would mean the ECB would be providing open-ended financing of Italy’s fiscal spending, something likely to be against all the ‘Maastricht’ rules for the Eurozone.

The ECB is caught in what one analyst called a “nightmare scenario”. The deputy head of the Brussels-based Bruegel economic think tank, Maria Demertzis said, “The risk ahead of us is that because of the energy crisis, the euro area could end up in recession, while at the same time the ECB will have to keep raising rates if inflation does not come down.” Krishna Guha, head of policy and central bank strategy at US investment bank Evercore, said: “The combination of a brewing giant stagflationary shock from weaponised Russian natural gas and a political crisis in Italy is about as close to a perfect storm as can be imagined for the ECB.”

Looking across the pond at the USA.

As far as reporting, this will be one the year’s decisive weeks. One third of S&P 500 corporations report including big hitters like Apple, the FED sits or shits itself, and GDP results come out. We will have a much clearer picture by the end of the week and noteworthy will be the outlooks for future earnings by these corporations. Will Powell still be sprouting his nonsense about a strengthening economy, doubt it.

Michael is right to say that the Commerce Department may not rule the economy to be in recession due to the employment figures despite two consecutive quarterly falls in GDP which incidentally are mid-range for the average post-war recession. There is another way of looking at employment data which investors like Buffet find more revealing and that is to examine what is happening to “withheld taxes”. These are the taxes paid by companies on behalf of their employees each month to the Internal Revenue Service. All things being equal these taxes will grow as employment and wages rise, and conversely they will fall if employment fall.

The US fiscal year begins in October each year and ends in September. So let us look at the data from March which Michael correctly pointed out was the beginning of the softening of the data as recorded by the Household data. So using the data found in the links following, the monthly running total in March (month 6) was $273 billion and by June that had fallen to $262 billion (month 9) a fall of 4%. In addition the figure for June itself was $254 billion. Add in the 5.2% annual rise in wages and the adjusted total fall is between 5 and 6% in withheld taxes. This suggests a significant fall in employment beyond that expressed by the Household data. https://www.cbo.gov/system/files?file=2022-07/58219-MBR.pdf and https://www.cbo.gov/system/files?file=2022-04/57909-MBR.pdf

Those who are familiar with my posts will know that I am very disappointed with the quality of the reports coming out on retail sales, personal consumption expenditures and employment data.

One jaw of the trap is recession and the other is inflation, right?

I tend to think of the spirit of the EU as Maastricht, not Schengen. The teeth of the inflation jaw cut creditors. Before Keynes, it was agreed that it was essential to abide by the gold standard because, real money. We may use credit/fiat currency now but inflation makes that not real money and hurts creditors. So far as I can see this jaw is a terrifying menace.

The other jaw is recession. Despite the recent increase in efforts to portray inflation as the greatest scourge of the working class, the greatest theft of the wealth of nations since going off the gold standard and, not least, the solvent of civilization in general, the hardest hit victims of recession are workers. So far as I can see this jaw is not so terrifying, maybe even a painful discipline for the unruly masses.

I’m not seeing that the masters of the EU really feel badly gored by the horns of the dilemma, to switch metaphors. They seem to be pretty sure they can survive the little dull horn, so long as they dodge the huge, sharp, lethal horn.

Unless they fear the breakup of the EU?

Many people here in Europe (more as time passes since the initial Orwellian hysteria about Ukraine, which apparently justified shooting ourselves in the knee over and over in neo-Christian self-martyrological fervor) understand that we’re being driven to the slaughterhouse, to become docile US colony that can only purchase what is sanctioned by the Pentagon (nobody seems to think the White House has much control anymore). However I’d say this has been going from before and underlines how subordinated European capital is relative to US one: it happened with Trump abusing NATO’s hierarchy to make Europe pay for military bases that were built decades ago and massively increase military spending (which mostly caters to US corporations), it happened even more dramatically when the US sub-prime crisis was redirected against Europe, it happened even before when Germany’s booming trade with Iran was “cancelled” by US sanctions, etc.

Europe is however about the only colony the USA still has. It also has Japan, Australia and such but these can’t be exploited as they are true frontline colonies against China (Russia is not the primary enemy at all, it could even become a US ally in the event of a sovereign Europe, which won’t happen but is a risk they do consider). This means that the weight of US imperial/metropolitan needs on this subcontinent is set to become very quickly a massive burden, as the US Empire can’t suckle from any other place or almost so (the Global South is not anymore mesmerized by Uncle Sam’s stare, nor scared either it seems). The pressure seems it will turn into stronger fascism, more authoritarianism and from a growingly far right position (a true Mussolinian is about to become Italian PM this fall), sadly I don’t see near any socialist uprising (except maybe in France, but it will surely be contained by force plus propaganda). We’ll see what happens but I’m rather scared by these developments, it now seems nothing will go even slightly better in maybe a decade.

Estimado Michael Roberts, todas las semanas leo con avidez sus trabajos y le agradezco el hacerlos llegar.Una pregunta y perdone la impertinencia de distraer su atención. La baja de la tasa de ganancia causa serios problemas en los países desarrollados, en Argentina se da una situación paradójica, empresas del rubro alimentación obtuvieron en los dos últimos años ganancias superiores al 400%, en la metalurgia lograron algo más del 200%. ¿ A qué se deben esos montos ? ¿ A la posición oligopólica ? ¿ A los bajos salarios ? ¿ El capital fijo no ha desplazado lo suficiente al capital variable ? Perdone la molestia y nuevamente gracias por sus trabajos .

I think you should try to question in english, because this is an english site. Surely you get more answers in that way. Btw, where you get this profits data? 400%, 200%… you mean profits before tax over fixed capital? Really? Be careful with the data that certain left-wing leaders shout in the media in Argentina. Usually, the same people that exclaim that capitalism is on permanent crisis, they tend to report extraordinary monopoly profits of that kind.

Yes, this is monopoly rent. It doesn’t mean the general (social) rate of profit is rising (on the contrary, it usually is a symptom of its fall).

In Europe’s case, for example, energy companies are registering legendary profits. That’s a result of the absolute scarcity of energy plus their monopoly or oligopoly position on the commodity.