The Governor of the Bank of England, Andrew Bailey set the attitude of the mainstream view on the impact of inflation in February, when he said that “I’m not saying nobody gets a pay rise, don’t get me wrong. But what I am saying is, we do need to see restraint in pay bargaining, otherwise it will get out of control”.

Bailey followed the Keynesian explanation of rising inflation as being the result of a tight (‘full employment’) labour market allowing workers to push for higher wages and thus forcing employers to hike prices to sustain profits. This ‘wage-push’ theory of inflation has been refuted both theoretically and empirically, as I have shown in several previous posts.

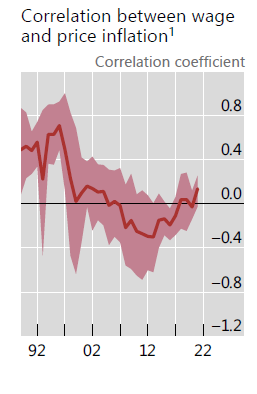

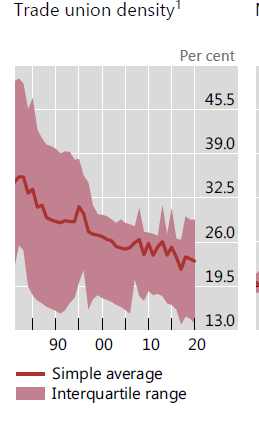

And more recently the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) study confirms that “by some measures, the current environment does not look conducive to such a spiral. After all, the correlation between wage growth and inflation has declined over recent decades and is currently near historical lows.”

But this wage push theory persists among orthodox Keynesians because they think full employment breeds inflation; and it is supported by the authorities because it ignores any impact on prices by businesses attempting to boost profit. Bailey did not talk about ‘restraint’ in market pricing or profits.

The wage-push theory existed before Keynes. As far back as in the mid-19th century, the neo-Ricardian trade unionist Thomas Weston argued in the circles of the International Working Man’s Association that workers could not push for wages that were higher than the cost of subsistence because it would only lead to employers hiking prices and was therefore self-defeating. For Weston, there was an ‘iron law’ of real wages tied to the labour time required for subsistence which could not be broken.

Marx rebutted Weston’s views both theoretically and empirically in a series of speeches published in the pamphlet, Value Price and Profit. Marx argued that the value (price) of commodity ultimately depended on the average labour time taken to produce it. But that meant the shares of that labour time between the workers who created the commodity and the capitalist who owned it was not fixed but depended on the class struggle between employers and employed. As he said, “capitalists cannot raise or lower wages merely at their whim, nor can they raise prices at will in order to make up for lost profits resulting from an increase in wages.” If wages are ‘restrained’ that may not lower prices but instead simply increase profits.

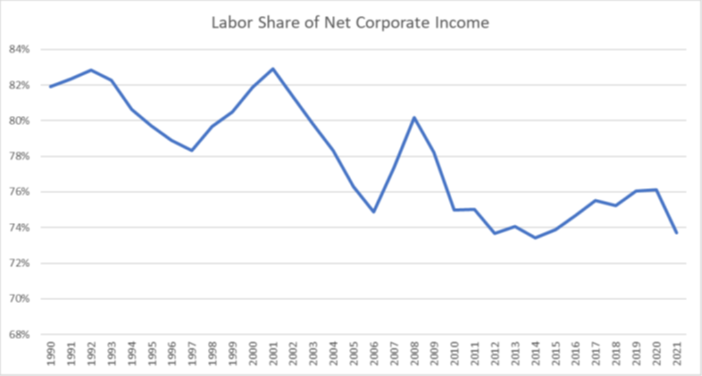

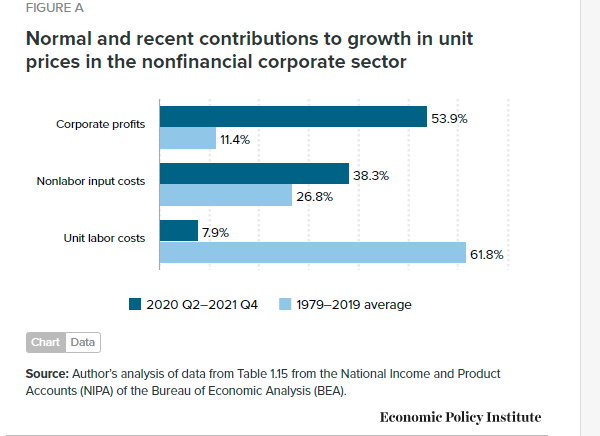

Indeed, that is what is happening now in the current bout of inflation. In the Great Recession recovery, price growth was actually quite subdued over the first few years of that recovery. Corporations instead applied extreme wage suppression (aided by high and persistent levels of unemployment). Unit labour costs (ie the cost of labour per unit of production) fell over a three-year stretch from the recession’s trough in the second quarter of 2009 to the middle of 2012.

There has been a general pattern of the labour share of income falling during the early phase of recoveries characterized most of the post–World War II recoveries, though it has become more extreme in recent business cycles. By 2019, labour’s share was at all-time low. The decade of the 2010s saw basically a stagnation of average real wages in most major economies.

In a recent report, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) makes the point that “in recent decades, workers’ collective bargaining power has declined alongside falling trade union membership. Relatedly, the indexation and COLA clauses that fuelled past wage-price spirals are less prevalent. In the euro area, the share of private sector employees whose contracts involve a formal role for inflation in wage-setting fell from 24% in 2008 to 16% in 2021. COLA coverage in the United States hovered around 25% in the 1960s and rose to about 60% during the inflationary episode of the late 1970s and early 1980s, but rapidly declined to 20% by the mid-1990s “

Since the COVID slump, labour’s share of income and real wages have been falling sharply even as unemployment falls. This is the complete opposite of the Keynesian inflation theory and the so-called ‘iron law of wages’ proposed by Weston against Marx. The rise in inflation has not been driven by anything that looks like an overheating labour market—instead it has been driven by higher corporate profit margins and supply-chain bottlenecks. That means that central banks hiking interest rates to ‘cool down’ labour markets and reduce wage rises will have little effect on inflation and are more likely to cause stagnation in investment and consumption, thus provoking a slump.

Prices of commodities can be broken down into the three main components: labour costs (v= the value of labour power in Marxist terminology), non-labour inputs (c =the constant capital consumed), and the “mark-up” of profits over the first two components (s = surplus value appropriated by the capitalist owners). P = v + c + s.

The Economic Policy Institute reckons that, since the trough of the COVID-19 recession in the second quarter of 2020, overall prices in the producing sector of the US economy have risen at an annualised rate of 6.1%—a pronounced acceleration over the 1.8% price growth that characterized the pre-pandemic business cycle of 2007–2019. Over half of this increase (53.9%) can be attributed to fatter profit margins, with labour costs contributing less than 8% of this increase. This is not normal. From 1979 to 2019, profits only contributed about 11% to price growth and labour costs over 60%. Non labour inputs (raw materials and components) are also driving up prices more than usual in the current economic recovery.

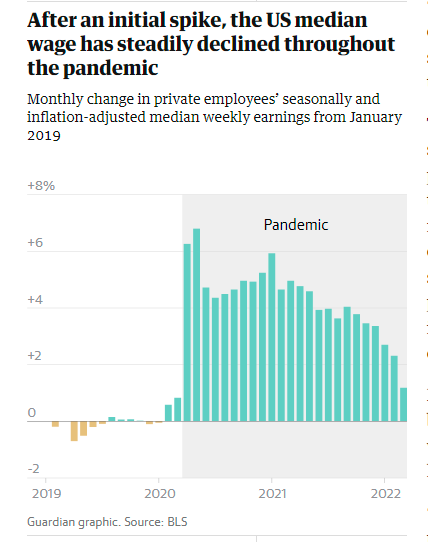

Current inflation is concentrated in the goods sector (particularly durable goods), driven by a collapse of supply chains in durable goods (with rolling port shutdowns around the world). The bottleneck is not labour asking for higher wages, it is the lack of shipping capacity and other non-labour shortages. Indeed, in the current inflation spike, US weekly earnings growth has been slowing month by month.

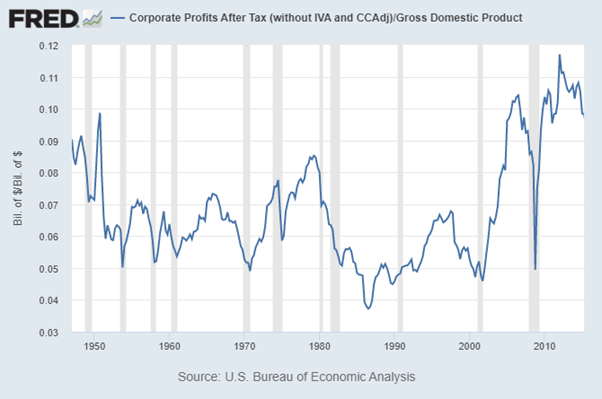

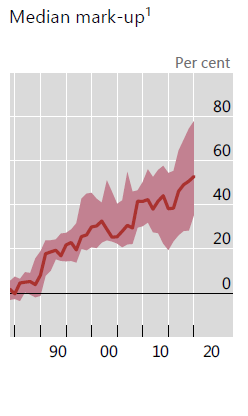

It’s profits that have been spiralling upwards. Firms that did happen to have supply on hand as the pandemic-driven demand surge hit have had enormous pricing power vis-à-vis their customers. Corporate profit margins (the share going to profits per unit of production) are at their highest since 1950.

The BIS study finds similarly: “Firms’ pricing power, as measured by the markup of prices over costs, has increased to historical highs. In the low and stable inflation environment of the pre-pandemic era, higher markups lowered wage-price pass-through. But in a high inflation environment, higher markups could fuel inflation as businesses pay more attention to aggregate price growth and incorporate it into their pricing decisions. Indeed, this could be one reason why inflationary pressures have broadened recently in sectors that were not directly hit by bottlenecks.”

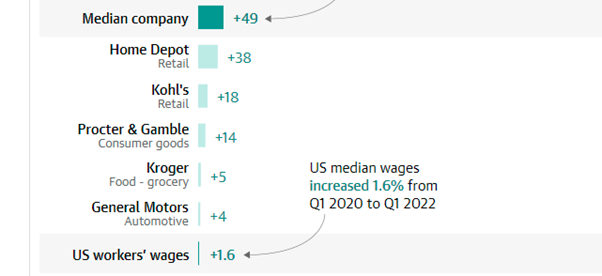

An analysis of the Securities and Exchange Commission filings for 100 US corporations found net profits up by a median of 49% in the last two years and in one case by as much as 111,000%!

Chief executives are acutely aware of the ability to hike prices in this inflationary spiral. Hershey bar CEO Michel Buck told shareholders: “Pricing will be an important lever for us this year and is expected to drive most of our growth.” Similarly, a Kroger executive told investors “a little bit of inflation is always good for our business”, while Hostess’s CEO in March said rising prices across the economy “helps” profits.

Does this mean that companies can raise prices at will and are engaged in what is called ‘price-gouging’? Marx, arguing with Weston in 1865, did not think that was the case in general. The power of competition still ruled. George Pearkes, an analyst at Bespoke Investment, pointed to Caterpillar, which recorded a 958% profit increase driven by volume growth and price realization between 2019 and 2021’s fourth quarters. Eliminating price increases may have dropped the company’s 2021 quarter four operating profits slightly below the $1.3bn it made in 2020. “This isn’t price gouging … and it shows pretty concretely that there’s a lot of nuance here,” Pearkes said, adding profiteering is “not the primary driver of inflation, nor the primary driver of corporate profits”. Indeed, companies that push prices as hard as the current environment allows to maximise profits in the short run may find themselves paying a price in market share down the road as others get into the game. It is clear, however, that the concentration of capital is any sector, the greater ability to hike prices. “When you go from 15 to 10 companies, not much changes,” one analyst argued. “When you go from 10 to six, a lot changes. But when you go from six to four – it’s a fix.”

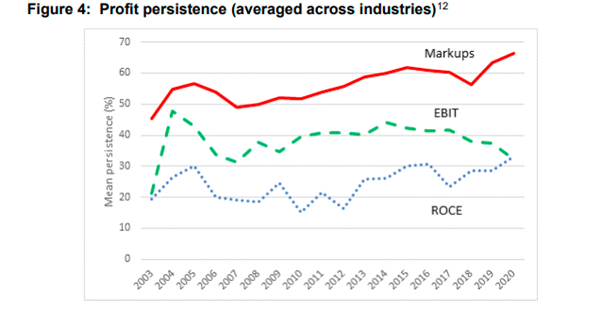

Recently, the UK’s Competitions and Market Authority (CMA) published an important report. The CMA found a mixed picture.Profit persistence has increased as measured by markups over marginal costs and the return on capital but not when measured by profits before tax.

And the CMA also found that the more international competition there was, the less ability for firms to increase prices and mark-ups. “This highlights the important role that international trade plays in contributing to keeping UK markets competitive.” The BIS summed up this debate: “In product markets, the degree of competition comes into play. Firms with higher markups – an indication of greater market power – could raise prices when wages increase, while those without such pricing power may hesitate to do so. Strategic considerations in price-setting are also relevant. Firms may feel more comfortable raising prices if they believe their competitors will also do so. Price increases are more likely when demand is strong. With less concern about losing sales and less room to adjust profit margins, even firms with less pricing power could pass higher costs through to customers.”

As a partner in the Bain consultancy, an adviser to many corporations, argued, “when times are tough, screw your customers while the screwing is good!”. The consultant went on: “I don’t think this is actually nefarious at all. Companies should charge what they can. Profit is the point of the whole exercise.”

Thanks for this interesting and comprehensive post. Three points/questions:

(1) If demand is strong and this makes it easier for firms to raise prices, this demand-pull element of inflation can presumably be reduced through tighter monetary and/or fiscal policy.

(2) If firms do take advantage of current conditions to raise prices faster and increase profits, will these profits be reinvested productively and raise output and productivity in the future?

(3) Higher inflation can lead to more rapid changes in the distribution of income between economic sectors, but I suppose it is an open question whether or not such changes ultimately benefit the economy as a whole or merely create price distortions which dampen productive activity.

Bravo, excellent article with incontrovertible conclusions.

Looking into the future and watching Bloomberg, the crashing stock market is being caused by profit margins compressing (falling). The markets are re-evaluating profit margins and are terrified by what they are seeing. The large corporations in bleeding their customers white will pay a hefty oops I mean a lower price in the immediate future. Its much as I said would happen as demand falls inventory builds and supply chain price rises persist, and all this against a background of tighter liquidity. A perfect storm.

On the issue of elevated margins since 2000 and William Jeffries take on profitability. How does your view of the great depression square with these elevated profit margins prior to 2020. (Your FRED graph) Surely those profit margins are more in accord with Marx’s views on the phase of prosperity. I hope you answer this question because soon we will be in agreement because that is exactly where the world economy is now heading.

“The Guardian’s data, he added, objectively shows a massive “transfer of wealth” from consumers, who pay higher prices, to shareholders and investment firms that reap the benefits.” — from the Guardian article, liked below “100 US corporations found net profits up by a median of 49% in the last two years” – good to at last read a complete article about inflation’s causes.

The corporate profits chart contains a measurement error (selected quotes).

[quote]

This latter chart, CPATAX/GDP, and that of its twin brother, CPATAX/GNP, is an illusory result of flawed macroeconomic accounting. In the paragraphs that follow, I’m going to try to clearly and intuitively explain why. Hopefully, the chart will disappear once and for all.

CPATAX/GDP: Identifying the Mistake

The expression CPATAX/GDP contains an obvious distortion. CPATAX is a “national” term–it refers to the after-tax profit of all U.S. resident corporations, whether that profit is earned domestically, or from operations in a foreign country. GDP, in contrast, is a “domestic” term–it refers to the total gross output (and therefore the total gross income) produced (and earned) inside the United States, whether that income is earned by U.S. residents or by foreign entities.

Notice that if a U.S. corporation earns a profit from affiliate operations abroad, the profit will be added to the numerator of CPATAX/GDP, but the costs will not be added to the denominator, as they should be in a “profit margin” analysis. Those costs, the compensation that the U.S. corporation pays to the entire foreign value-added chain–the workers, supervisors, suppliers, contractors, advertisers, and so on–are not part of U.S. GDP. They are a part of the GDP of other countries. Additionally, the profit that accrues to the U.S. corporation will not be added to the denominator, as it should be–again, it was not earned from operations inside the United States. In effect, nothing will be added to the denominator, even though profit was added to the numerator.

General Motors (GM) operates numerous plants in China. Suppose that one of these plants produces and sells one extra car. The profit will be added to CPATAX–a U.S. resident corporation, through its foreign affiliate, has earned money. But the wages and salaries paid to the workers and supervisors at the plant, and the compensation paid to the domestic suppliers, advertisers, contractors, and so on, will not be added to GDP, because the activities did not take place inside the United States. They took place in China, and therefore they belong to Chinese GDP. So, in effect, CPATAX/GDP will increase as if the sale entailed a 100% profit margin–actually, an infinite profit margin. Positive profit on a revenue of zero. —Profit Margins: The Death of a Chart

[end quote]

—Profit Margins: The Death of a Chart

source: https://www.philosophicaleconomics.com/2014/03/foreignpm/

Correct. That is why I derive profit margins only using NIPA Table 1.14 which is domestically produced profits. Though to be fair the transfer of value resulting in the underpricing of inputs (imports) versus fully priced outputs which forms GVA exceeds the mass of net foreign profits. Still what is useful about Michael’s FRED graph is it shows how much the US benefited from globalisation.

“It shows how much the US benefited by globalization.”

Right. But Ahmed shows the futility of using capitalism’s data in dealing with US corporate profitability.

The domestic economy of the United States’s is military keynesian, and has been increasingly from WW2 to the present. In today’s irrationally refined, neoliberal incarnation, the US’s main product is war and the threat of war. If you add up the costs of US of arms production+ maintaining and deployment of publicly acknowledged government armies, navies, air forces as well as private mercenary forces+maintaining 800+ foreign bases+18 known intelligence agencies+secret US biological and chemical warfare sites+permanently deployed jihadist and fascist mercenary forces (open and subliminal world wide)+ the surveilance state’s massive domestic and global operations, you will come up with a a figure that dwarfs the gross domestic value of all US producers of non-destrucive goods and services.

The economy of the US and, maybe democratic Englandand the fascist democracy,Israel, are unique: their “democracies”, or, rather, their embedded transnational corporations don’t compete with other countries or businesses for profit. They extort the world’s surplus by massively destructive regime change, or through their already established comprador extorters. The “democratization” of Ukraine is a good example of the process.

Having pointed out the obvious, I must agree with your assessment of this post: excellent with incontrovertible conclusions. I think Ahmed Fares would agree. Roberts shows the weakness at the heart of imperialism, by taking the capitalists view of their system’s workings at face value, and then going on to show that, even so, the system’s unsustainable….analogous to the analytical approach of Marx in Capital…. It’s uncanny how many Western marxists miss the point of Capital as a “critique” of political economy, and end up worshipping capitalism as social imperialists. Not all the anti-imperialists are in the Global South. How do we come together?

I see Bank of America, having aggregated corporate statements and outlooks finds that the highest number since the beginning of the pandemic, have pointed to weakening demand. Wonder how long before wall street changes its tune about strong demand. Even the perennially optimistic ISM has focused on the collapse of new orders

Saw this…”Capitalism’s history shows aftermath booms like the more common cyclical booms, end only when the economy runs up against a growing money shortage and credit dries up. The underlying reason is the quantity of non-money commodities — measured in terms of the money commodity’s use value or in terms of labor values — expands at faster rates than the money commodity’s quantity — also measured in terms of the money commodity’s use value or labor value.”

It seems to me that credit doesn’t dry up because money (gold) runs out but because profits dry up. They aren’t sufficient to repay old loans, entice lenders to make new loans, provide enough of a lure for capitalists to make new investments, etc. The second sentence has an aside about the use value of the money commodity (again, gold) without explaining what the use value of “the” money commodity is. And the very last phrase, “the money commodity’s use value or labor value” implies they are equivalent. Wasn’t Marx’s whole point of the commodity analysis opening Capital that use value and labor value are not the same? That’s why the economic harmony is a fluke, not a necessity?

This all seems more mercantilist than Adam Smith, who sometimes seems to have lived in vain. The true wealth of nations is found, in Smith’s vision, in the division of labor, not commodities, even money commodity (gold wasn’t even the only money commodity in his time.) In this century, the wealthier the nation, the more credit created by this social development of the division of labor, serves as a medium of economic life. Internationally, the credit is inextricably tied to national power. The dollar is founded on blood, not gold, in that sense.

The secular decline in profit rates for the world capitalist system makes new investment less promising, hence the resort to fictitious capital, right? But the lack of investment means the relative decline in output, aggravated because the population is not declining.* Could there be increasing tendencies for shortages of goods caused by the decay of capitalism, that they are not just accidents of nature? Competition between capitalists in a declining system would possibly take the form of deliberately restricting production. Rather than investing in new capital to seize market share, marginal product lines and marginal markets are simply dropped. Rather than lowering prices to make money on lower production, price rises are the main mode of profit realization. And so on and so forth.

*The bourgeoisie is flirting with the idea there are just too many people. Hence, their increasing attraction to fascism. Others may think the bourgeoisie is innately bourgeois democratic but I think capitalism started with the expropriation of Church lands. And bourgeois democracy was created by the masses by class struggle. The bourgeois social formation is not just a business plan. Freedom as people usually mean it was born in the great revolutions.

“And the very last phrase, “the money commodity’s use value or labor value” implies they are equivalent. Wasn’t Marx’s whole point of the commodity analysis opening Capital that use value and labor value are not the same? That’s why the economic harmony is a fluke, not a necessity?”

Value is the mere quantification and symbolization of use value.

Money is the universal commodity: the commodity which can be exchanged for every other commodity.

Labor is the objectification of the human being (the human being as a thing). As a thing, human existence can be expressed materially, therefore also quantitatively, in the capitalist system, as use value and value.

The loss of use value implies in the destruction of value.

I though value was the socially necessary abstract labor power expended. Apparently I don’t understand Marxism at all. I suppose I should take the lesson of Henry Rech’s negative example.

“I though value was the socially necessary abstract labor power expended.”

Yes, but use value is the Träger des Tauschwerts, literally the support of the exchange value.

Deep down, human beings are just things (i.e. natural beings, stuff from nature). That’s why humans cannot create value in abstract, in the kingdom of pure mathematics. This also means humans cannot have a soul in the Christian/Jewish/Islamic or any other similar religious sense of the word, and why the Spirit (in the philosophical sense) cannot possibly exist. Marx proved, scientifically, that humans for certain do not have a soul, and, therefore, that there’s no spiritual world beyond our world (i.e. no Heaven and no Hell). There’s absolutely no spiritual aspect of the human being; even madness and delirium have their firm, objective material base.

Michael, do you think current lockdown measures in Shanghai contribute to inflation? And if so, what are the potential hazards for China and the US from this?

The lockdowns are clearly having an effect n Chinese production but I think this is temporary and will not be decisive in the global trade and inflation.

https://markets.jpmorgan.com/research/email/-o2tb3r8/35g6hToq84X5xKOHZXLUmQ/GPS-4093089-0

Michael, the rolling port shutdowns being the drive of supply chain disruptions drives me crazy!! Especially in the port of LA, labor is more than willing to work those jobs – take a look at how one becomes a longshoresman in the US, you are only allowed to work “casually” (i.e. well under part-time hours) for a certain number of years before being allowed to apply for a position by lottery. Even in these conditions! And I’m almost certain it’s because the longeshoresmen’s union is strong and militant, they’d rather risk the legitimacy of the system rot due to inflation, or even more grotesquely with the baby formula shortage, than allow more workers into a union shop.

There are plenty of experienced workers in the reserve army who could take up positions in the Port of LA and Longbeach, many have held casual positions for years, all they have to do is hire them!

Not sure how similar this story is around the world but I wouldn’t be surprised.

“The bottleneck is not labour asking for higher wages, shipping capacity and other non-labour shortages.”

Is there meant to be a “it is” between “higher wages,” and “shipping” here?

good spot! will fix