Global economic growth is slowing. There is a global manufacturing recession already in place: the latest surveys of economic activity in the major economies show that there is an outright contraction in manufacturing in all the major economies – and it is getting worse.

US ISM manufacturing index (score below 50 means contraction)

But inflation of prices outside of food and energy, the so-called core inflation rate, is not falling in the major economies.

Central bank chiefs continue to shout the mantra that interest rates must rise to reduce ‘excessive demand’ in order to get demand back in line with supply and so reduce inflation. But the risk is that ‘excessive’ interest rate hikes will accelerate economies into a slump before that happens and also engender a banking and financial crisis as indebted companies go bust and weak banks suffer runs on their deposits.

The stock markets of the world remain sanguine and head up to highs based on the view of investors that a ‘soft landing’ will be achieved ie a decline in inflation to the central bank targets without a substantial contraction in investment, output and employment.

Yet all the portents remain that the major economies face a new slump ahead. First, inflation remains ‘sticky’ not because wage rises (or spending) from labour have been ‘excessive’, contrary to view of central bankers and mainstream economic pundits. As I and others have argued before, it is the poor recovery in output and productivity coupled with a very slow return to international transport of raw materials and components that kicked off the inflationary spiral – not workers demanding higher wages.

If anything, it is ‘excessive profits’ that have driven up prices. Taking advantage of supply chain blockages after the COVID pandemic and shortages of key materials, multi-national companies in energy, food and communications raised prices to reap higher profits. The case for ‘sellers inflation’ was kicked off by analyses by Isabelle Weber and others that forced even the official monetary authorities to admit that it was capital and profits that gained while labour and nominal wages took the brunt of the cost of living rises.

The ECB and the IMF have since published reports admitting the role of profits in inflation. The IMF joined the growing chorus that inflation was really driven by rising raw material import prices and then by rising corporate profits, not wages.

“Rising corporate profits account for almost half the increase in Europe’s inflation over the past two years as companies increased prices by more than spiking costs of imported energy.” This contradicted the claims of the heads of the US Federal Reserve and the Bank of England that a ‘hot labour market’ and wages were the drivers of a wage-price spiral.

The trendy phrase in vogue is ‘greedflation’, implying that companies had greedily hiked the margin between costs and prices to boost profits. But the evidence for increased profit margins is dubious. Profit margins are high in the US, but after peaking at the end of 2022, they have been falling back since.

In a new study for France, Axelle Arquié & MalteThie found that price rises were greater where firms had ‘market power’ and this explained ‘sellers inflation’: “in sectors with higher markups, prices increase relatively more: in the least competitive sector, firms pass through up to 110% of the energy shock, implying an excess pass-through of 10 percentage points. In addition, we find that the association between markup and pass-through is even higher when markup dispersion is low, consistent with the argument that firms engage in price hikes when they expect their competitors to do the same.”

On the other hand, in the UK there appears to have been no increase in the profit share of corporate output value.

The Bank of England economist Jonathan Haskell also argued that there is little evidence that rising profit margins are the main cause of accelerating inflation. In the three years since 2019, average prices for consumption goods have increased 16.8% in the UK, 13% in the US and 14.7% in the Euro area. Of that increase, labour costs contributed about half the rise in the UK, 60% in the US and 40% in the Eurozone. The rise in profits contributed only around 30% in each area. What was interesting is that when productivity growth (TFP) fell (as in the UK) that raised prices much more.

So is it a profits-price spiral or a wage-price spiral? This question has led to an intense debate between mainstream economists and more heterodox ones, although the ideological division has been blurred with some on both sides of debate: is inflation a ‘sellers inflation’ or ‘greedflation’ from the corporations; or is it the result of ‘tight’ labour markets allowing workers to hike wages and force companies to raise prices; or is it, as the monetarists argue, just too much money supply chasing too few goods?

Whatever the case, the IMF is worried that as workers try for higher wages to compensate for rising prices, “companies may have to accept a smaller profit share if inflation is to remain on track .” Similarly, the Bank for International Settlements talks about this in its new Annual Economic Report. “The surprising inflation surge has substantially eroded the purchasing power of wages. It would be unreasonable to expect that wage earners would not try to catch up, not least since labor markets remain very tight. In a number of countries, wage demands have been rising, indexation clauses have been gaining ground and signs of more forceful bargaining, including strikes, have emerged. If wages do catch up, the key question will be whether firms absorb the higher costs or pass them on.”

Here the arch-monetarist BIS hints at the need for companies to “absorb higher costs” by accepting “lower profit margins.” But as it points out “Should wages increase more significantly—by, say, the 5.5 percent rate needed to guide real wages back to their pre-pandemic level by end-2024—the profit share would have to drop to the lowest level since the mid-1990s (barring any unexpected increase in productivity) for inflation to return to target.”

Either way, the debate has switched to whether the central banks should continue to increase interest rates to try and get inflation down to the arbitrary target of 2% or instead let inflation stay higher and for longer rather than provoke a slump.

Arch Keynesian, Martin Wolf in the Financial Times made it clear where he stood. As a true Keynesian, he wanted ‘demand’ driven down at all costs. “We are seeing a price-price and wage-price spiral radiating throughout the economy. The only way to halt this is to remove the accommodating demand. In other words, the question is not whether there will be a recession; it is rather whether there needs to be one, if the spiral is to be halted. The plausible view is that the answer to the latter part of this question is “yes”. Like it or not (I certainly do not), the economy will not get back to 2 percent inflation without a sharp slowdown and higher unemployment.”

Wolf concluded that “In sum, rates may have to rise again.” Should governments help households with the rising cost of borrowing and servicing debt? “The answer is: absolutely not. that this would defeat the object of the exercise, which is to tighten demand. If fiscal policy were to offset this, monetary policy would have to be still tighter than otherwise. If the desire is to moderate the monetary squeeze, fiscal policy should be tightened, not loosened.” So Wolf advocates both fiscal and monetary austerity.

You see, he said, we cannot accept a relaxation of the target for inflation because if “a country abandons its solemn promise to stabilise the value of the currency as soon as it becomes hard to deliver, other commitments must also be devalued.” Here Wolf repeats the view of Keynes himself on inflation: wrote (pdf): “Lenin was certainly right. There is no subtler, no surer means of overturning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency.” This expresses the fear of economies with weaker currencies compared to the dollar – not just the UK, but particularly all the ‘emerging’ economies currently deep in debt distress. Whichever is tougher on austerity can avoid a weak currency and inflation but instead get a deep slump. It’s trade-off for many countries.

The austerity option upset the maverick former Bank of England chief economist, Andy Haldane who wrote: “the textbook role of monetary policy is to tolerate, not offset, these temporary inflation misses provided inflation expectations remain anchored. Not to do so inflicts unnecessary further damage on growth”, he claimed in opposition to the central bank chiefs and Wolf. So what if there is higher inflation: “at 3-4 per cent, inflation no longer enters the public consciousness. there is essentially no evidence it would impose costs that are any greater than at 2per cent. But the costs of lowering inflation those extra few percentage points, measured in lost incomes and jobs, are larger at these levels of inflation. Squeezing the last drops, at speed, would mean sacrificing many thousands of jobs for negligible benefit.” So let’s tolerate higher inflation.

As he put it: “Imagine a doctor, uncertain about the nature and severity of a disease, who has administered a large medicinal dose which has yet to take effect. Prudence would cause them to pause to see how the patient responded before doubling the dosage. That principle is one central banks should heed now to avoid overdosing the economy.” So let’s wait and see and let inflation take its course, he argues. But that means a longer and higher cut into living standards for workers as inflation stays higher and longer.

Star liberal leftist economic historian, Adam Tooze was equally affronted by Wolf’s orthodox position. “The angst now is about inflation persistence. Getting it back down to 2 per cent is the battle-cry. As it was half a century ago, this is a profoundly conservative political argument dressed in the garb of economic necessity. So this is where we have arrived in 2023: to bring inflation back to 2 per cent while preserving the banks, common sense insists that we need higher interest rates for longer, plus austerity. And, at this point, you have to ask whether western elites have learnt anything from the last decade and a half.” The call for austerity was “the old neoliberal logic of “there is no alternative”. Tooze argued that “in pursuit of lower inflation, monetary austerity risks the same fate. It is time to steer the stampeding herd away from the cliff edge, for the sake of the financial security of millions of people and the credibility of our policy institutions.”

So argument goes on among central bankers and economists. But what is missing from all this is what caused inflation to rise in the first place and why it stays ’sticky’. The recovery in output globally has been weak since the end of the pandemic. Growth in the productivity of labour (output per worker) has been low. Indeed in value terms (ie hours of work) supply has been flat or falling.

As a result any increase in spending or credit has ended up adding to price inflation. But nobody mentions that it is the failure of capitalist accumulation to boost the productivity of labour (and value creation); instead the argument is about whether labour or capital should take the hit; or whether inflation should be allowed to stay high or be driven down despite the risk of slump.

The BoE data above reveal that the lower is productivity growth, the higher is the sticky’ core inflation rate. And as the BIS also said above, inflation won’t come down without a slump unless productivity growth rises sharply.

Let me remind readers of the state of US labour productivity – and remember the US is the best performing major capitalist economy.

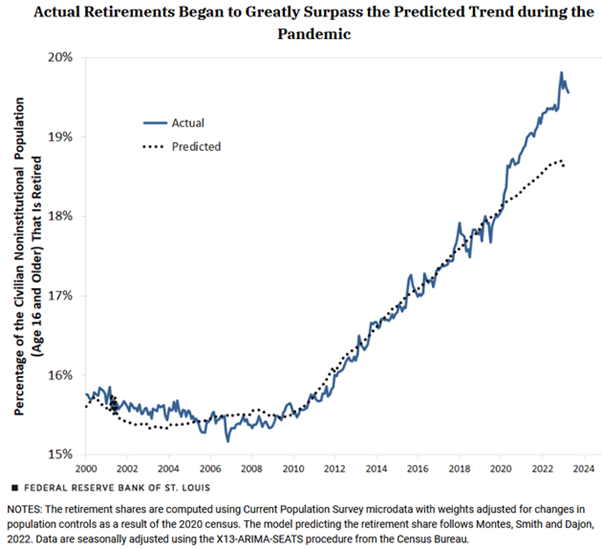

The reason the US labour market is ‘tight’ is not because the economy is expanding at a fast rate and delivering well-paid jobs for all. It is because so many skilled people of working age have left the labour market since the pandemic. Researchers at the St. Louis Fed estimate that the US has about 2.4 million “excess” retirees above the previously normal pace. If correct, that’s almost enough to explain the drop in participation rates.

Also immigration, a key driver of labour supply has diminished as many countries apply yet more restrictions. And so far, AI technology is not delivering faster productivity growth from the existing workforce.

Why is productivity growth not appearing? It’s because investment in technology is not picking up; instead companies prefer to find cheap labour even from a ‘tight’ labour market. Why is investment not picking up? It ‘s because the profitability of capital is still low and has not seen any significant shift up – outside of the small group of mega companies in energy, food and tech.

And while US real GDP has risen, that is not reflected in domestic income growth. There is a significant divergence between the gross domestic product (GDP) and gross domestic income (GDI). That divergence is due to both wages and profits (after inflation) falling. So, on a GDI basis, the US economy is already in recession.

Way back, I reckoned that the next recession would not be triggered by a housing bust or a stock market bust, or even a financial crash, but by increasing corporate debt costs, driving sections of the corporate sector into bankruptcy – namely ‘fallen angels’ and ‘zombie companies’. Corporate debt is still at record highs and whereas the cost of servicing that debt was comfortable for most due to low interest rates, that Is no longer the case.

The squeeze between falling profits and rising interest rates is tightening. We have already seen the impact of rising interest rates on the weaker sections of the banking system in the US and Europe. A record amount of commercial mortgages expire in 2023 and are set to test the financial health of small and regional banks already under pressure following the recent failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank. This year will be critical because about $270 billion in commercial mortgages held by banks are set to expire, according to Trepp—the highest figure on record. Most of these loans are held by banks with less than $250 billion in assets. In a recent paper, a group of economists estimated that the value of loans and securities held by banks is around $2.2 trillion lower than the book value on their balance sheets. That drop in value puts 186 banks at risk of failure if half their uninsured depositors decide to pull their money.

US Treasury Secretary Yellen is not worried, as she says the recent Federal Reserve ‘stress tests’ on banks showed that all could take any hit to capital from rising rates. But the tests also showed that the three banks that went under last March would have passed those tests! Chicago Fed President Austan Goolsbee compared the potential coming impact of the Fed’s 5 percentage points in rate increases to the unseen hazards faced by Wile E. Coyote, the unlucky cartoon character. “If you raise 500 basis points in one year, is there a huge rock that’s just floating overhead…that’s going to drop on us.”

And the pundits remain worried. Their estimate of a probability of a recession in the next 12 months is at 61%, historically high outside actual recessions.

Whatever the cause of rising inflation and whatever the argument over whether to keep to inflation targets, the major economies continue to slide towards a slump; the Eurozone is already there; and the US is going there whatever the stock market thinks and whatever the authorities claim. Far from a soft landing, it will be from stagflation to slumpflation.

Thanks for the round up. With so many conflicting forces in play, a c. 3% inflation target and slow retraction of money supply makes sense imho. Q: does 3% inflation (v. 2%) provide an increased incentive to put idle money at risk? At what point (4% eg) does higher inflation corrode the willingness to invest more than it incentivizes it?

questions:

a) “What was interesting is that when productivity growth (TFP) fell (as in the UK) that raised prices much more.”

But TableC shows higher inflation when TFP is positive (in the UK!!) and lower when TFP is negative! Did you get that wrong?

b) Regardless, isn’t labor productivity the value sold (realised) divided by the hours worked?

So if l. productivity is low or negative WHILE prices are up, this would mean that either hours worked too high (probably not true) or that the capitalists have trouble selling their products anyway, they sell less, so even with higher prices they get less value sold , so lower apparent productivity. (I say apparent, because this “productivity” is not the actual product per hour, but the GDP, the value it is sold at hour. That’s why i do not regard this reported “productivity” as a good crisis forecaster, as its decrease could as well be a byproduct of a crisis, lower sales and lower profits)

Now this TFP is not “labour productivity”, but “output” divided by (wages+capital). Is output the value sold or is it the actual products? I think the second here.

If TFP is low or negative WHILE prices are up, this would mean that either (wages+capital) are high OR less output is being produced. Why would the output fall? Because the markets have shrinked and maybe because investment in stable capital has been stalled, because of lower wages and international competition and trade wars?

c) The fact that the lower the TFP, the lower the inflation (US 13% inflation, while negative TFP) as Table C shows, could be coincidental as there are other factors playing into output production except for prices and capital invested (such as international markets and trade, meaning output to be exported therefore not influenced or influencing domestic consumer inflation?).

What do I get wrong??

Hi Vasilis Yes it is a bit confusing. But the table constructs factor contributions to inflation. So TFP adds to inflation if it is positive. That means total factor productivity was falling and so added to inflation in the UK while TFP deducted only a little from inflation (ie TFP growth was small), while TFP in the US was better and so deducted from inflation. If you add up the pluses and minuses you get the total figure. TFP is total factor productivity, the neoclassical aggregate production function residual after capital and labour inputs to total productivity. it is supposed to represent ‘innovation’. Again the story here is that the UK’s TFP made inflation higher and in the EZ slightly lower and in the US lower still.

According to Marx, there’s no such a thing as too high profits, excessive profits or super profits: there is only exploitation rates.

What one can say is that a rate of exploitation is high to the point the worker is receiving below his or her subsistence level, after which the very material base over which capitalism stands starts to degrade.

So, how do we use Marx’s theory in this case? I think Roberts et Carchedi’s Marxist theory of inflation is correct: labor productivity being constant or falling, the only way the capitalist class has to keep its profit rate from declining is through rising inflation for the working class at a rate higher than for itself. That must be the case because Marx was very clear, in volume III of Capital, that if individual capitalists merely rose their prices unilaterally, by their own freedom of enterprise, that would only mean a correspondent transfer of already produced value between hands. It has to be the initiative of the State, the only superstructure that has the means to direct inflation between antagonist classes (through the use of the Central Bank).

The State (Central Bank) then prints money in whatever fictitious capital form (financial product) so that the capitalist class receives the money first. The capitalist class then has room to rise their prices while keeping their accounts more or less stable, pushing down the purchase power of wages as a whole. The entirety of this newly emitted money has to be put on service of capital against labor (i.e. from the means of production to the means of consumption, in that order), in a very coordinated way. And Marxists also know which is the only capitalist sector capable of coordinating the capitalist class: the banking sector.

The First World countries have an additional problems in their hands: they are, by now, heavily deindustrialized, which means the majority of their working class in either unproductive or of very low productivity. The only way to raise “labor productivity” of these types of workers is by shortening the time of circulation. In other words, they would have not only to raise the OCC to higher levels than the productive sector, but also intensify the centralization of capital to a higher level. That would mean the petty bourgeoisie would have to be wipped out.

That the deindustrialization of the First World is relative and not absolute is irrelevant for this argument because, had it the productive base to raise supply back to their pre-pandemic levels, it would’ve already done so, one way or another, because, in the productive sector, you can raise productivity of labor through absolute extraction of surplus value. In a scenario where it is waging an existential war against socialism (China), that would mean working their industry and agriculture workers to death a la chattel slavery with the blessing of the State if it was deemed necessary. If supply has not risen in the First World, it is because it can’t do it, not because it doesn’t want to do it.

The only way out for capitalism is a new Kondratiev Cycle. If the capitalist world (i.e. the entire world excluding China and some othre minor countries) doesn’t manage to command resources and luck out (because scientific breakthroughs are also dependent on the mercy of the real world, it is not something humans can always rely on; that’s why I don’t consider the KC a true cycle, but only a possible cycle, a semi-circle that can or cannot be closed into a full circle) some new technology(ies) that are capable of triggering a new KC, it will continue to inexorably deteriorate into its material base. If that happens, humanity will be at a crossroads: socialism or a new long dark age (barbarism).

“If supply has not risen in the First World, it is because it CAN’T do it, …” -> Wonderful, you are knocking on Hell’s gates. Allow me to wide open them for you: “Global conventional crude oil production PEAKED in 2008 at 69.5 mb/d and has since fallen by around 2.5 mb/d.” Page 45 of the World Energy Outlook 2018 by the International Energy Agency. ¿And what about all liquids production: conventional + condensates + deep water + refinery gains + tight + tar sands + … ? ¿Are they about to peak? ¿Have they ALREADY peaked in 2018?

Well researched + informative = great article.

In viewing inflation the following analogy comes to light – the accelerator and the brake. The capitalists claim that when prices are rising, wage rises accelerate price rises and when prices are falling, elevated wage gains act as a brake preventing prices falling. Michael has dealt with the former issue comprehensively conclusively and admirably here and in previous articles, but we need to engage with the latter more effectively.

Yes, the great profit margin squeeze is on to rival the great profit margin surge before. It’s not only the issue of productivity, but of restructuring supply chains and the loss of least cost options, and of course El Nino which is likely to cause at least $4 trillion in losses. I suspect the mitigation by A.I. (job losses) will be marginal for the immediate future.

You raise an interesting point about the significant divergence between GDI and GDP. If we adopt the deflator found in NIPA Table 1.14 for US corporations rather than the Implicit GDP Deflator, it yields the lower GDI figure not the higher GDP figure, meaning that the US economy stopped growing a while ago. This is confirmed by the 11% fall in the tax-take or 16% in real terms after inflation (Oct-May) which despite a few confounding factors is not commensurate with a growing economy. Talking of which, the 7% budget deficit means fiscal and monetary policy are at logger heads meaning a higher peak in interest rates.

Finally, job gains and the effect on demand need to be taken with a pinch of salt. Job losses are concentrated amongst better paid workers, job gains amongst the lower paid. (Check out the Rolex index https://watchcharts.com/watches/brand_index/rolex#:~:text=The%20Rolex%20Market%20Index%20is%20an%20indicator%20of,%28in%20USD%29%20of%20these%2030%20watches%20over%20time.) In any case the delirious Bureau of Labour Statistics assumes the economy is expanding so they are weighting the balance of births and deaths of companies incorrectly, assuming more births which is adding 200,000 hypothetical jobs each month hence the disparity between the Establishment and Household surveys.

Given what is happening to the weather the title scorchflation is more appropriate.

Please explain how after a lifetime of working (since 1981) in manual working class jobs (20 yrs) and then lower level technical work (20 yrs) never being extravagant and foregoing avocado toast and fuzzy coffee….a comfortable retirement still alludes.

That’s one of the things this blog tries to explain.

Excellent write-up. A comment on output, productivity, profitflation:

Coming out of Covid, in Q4-2021 every finance minister and central bank in “the free world” started talking up inflation. So this was their plan from the get-go. Possibly as a means to drag us out of persistent disinflation, possibly for a lot more sinister reasons.

Businesses picked it up and started increasing prices, you can see that in the profits increase from Q1/Q2-2022.

Cost-of-living-crisis well established and followed up with increased interest rates (and increased bank profits), you get a further reduction in demand which is not reducing productivity as such, it is rather outright reducing OUTPUT. With lower sales, which off course necessitate higher prices again for businesses to produce the goods and services.

You may include here the boost in early retirements which also reduce income, hence spending power, hence demand, hence outright OUTPUT.

All this is very much a Western thingy.

What ALSO is very much a western thingy, is Climate Change and political promises towards UN 2030 to “save the planet”. In its wildest (genocidal) form, by reducing this planets population.

As Climate Change wasn’t universally believed or accepted and thus basically had lost its power to manipulate consumer behavior, luckily Covid came along (with policy application, forced vaccinations and whatnot) to force the necessary change (policy application again) on the planets population.

Next you know, Putin is messing up all the carefully engineered “save the planet” plans with his war against Ukraine (Nato, the Russian Cuba Crisis if you will).

Russia dodging sanctions by means of BRICS+, Russia and BRICS+ is developing a very different New World Order than what “the illiberal, undemocratic ‘our democracy’ rules based mental disorder” were looking to implement.

Short story going forward: To “save the planet”, Western countries (OECD, the Garden) will follow Japan development and go into decades and decades of stagflation and reduction in households wealth and purchasing power, all the while with aging populations to demand less and less goods and more and more geriatric services.

BRICS+ participating countries (the Jungle) will grow healthily.

Oddball