Next week 300 international organisations and 100 heads of state meet in Paris to discuss how “to build a more responsive, fairer and more inclusive international financial system to fight inequalities, finance the climate transition, and bring us closer to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals.” This meeting is in Paris because it is the so-called Paris Club that for over the last 60 years has monitored and managed loans and credit by governments and government-guaranteed private banks to the so-called developing countries – loosely called the Global South these days.

The meeting takes place when the situation for large sections of the Global South in the post-pandemic period is dire. There is much talk in the Global North of rising interest rates causing banking crises and threatening bankruptcies for so-called ‘zombie companies’ overloaded with debt. But this is nothing to the economic and social damage that low-income, high debt countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America are suffering.

It is more than a year since I wrote a post entitled The submerging debt crisis, in which I described the economic stress being placed on small, low-income economies around the world from food and energy inflation, rising interest rates and a strong dollar. Then I identified Ghana, Sri Lanka, Egypt and Argentina. Indeed, back as far as the middle of pandemic in 2020, I highlighted the growing debt disaster for over 30 ‘emerging’ economies, with many of the poorest people on the planet.

In the pandemic, the IMF and the World Bank agreed a limited moratorium on these countries servicing and repaying their debts. But this was not a cancellation and the moratorium is now over. And there was nothing done by the Paris Club debts or about the huge debts owed to private banks and other financial institutions, which continued to demand their pound of flesh. And since the end of the pandemic, the sharp rise in interest rates on global debt and a strong US dollar (much of global debt is in dollars) have forced yet more countries to the brink of default on payments and into further poverty.

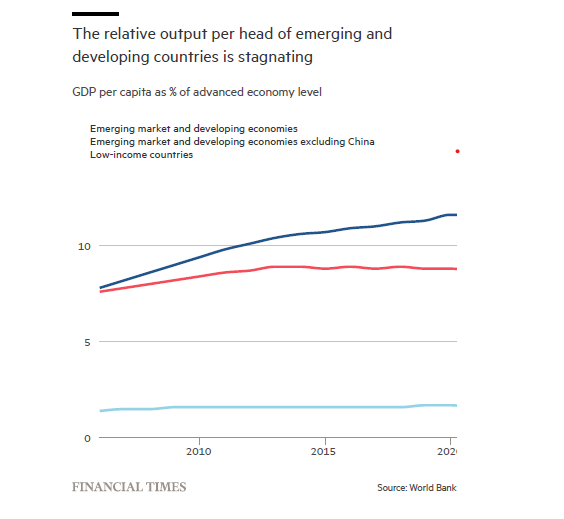

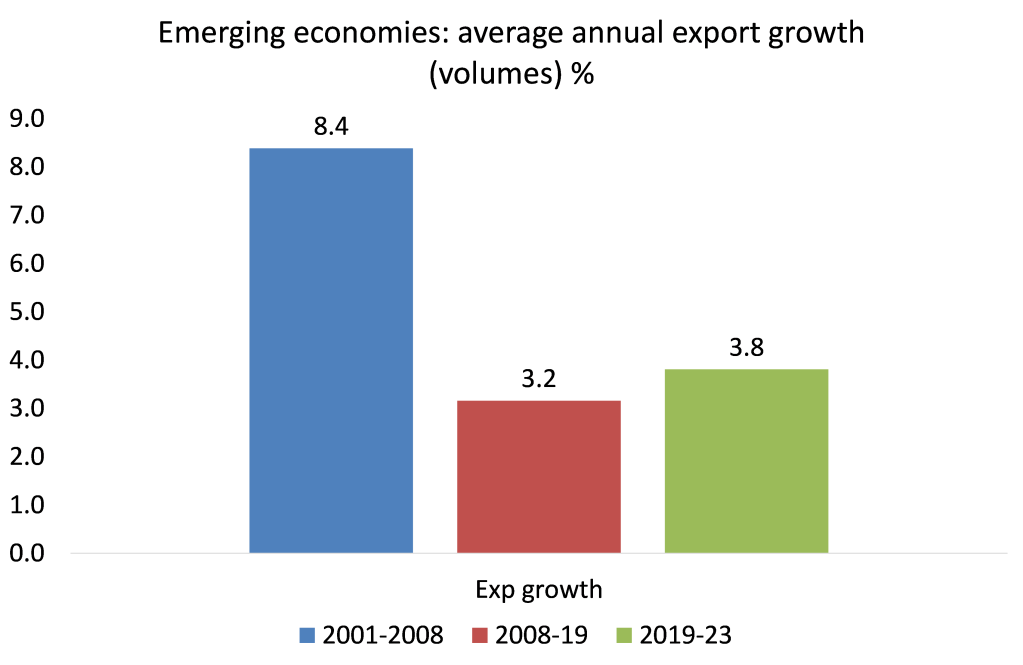

Most poor countries depend on selling raw materials and agricultural products or assembling manufacturing parts for the North. That means export revenues are vital to national income. But world trade growth has fallen away, particularly since the Great Recession of 2008-9 and even more since the pandemic. The volume of world trade grew at an average rate of 5.8% a year between 1970 to 2008, while GDP growth averaged 3.3%. But in the Long Depression of 2011 to 2023, average growth of world trade was a mere 3.4% a year, while global GDP growth averaged just 2.7%. Indeed, real GDP per head for the Global South, excluding China, has stagnated relative to advanced capitalist economies.

The reduction in world trade growth is particularly hard on ‘emerging’ economies. Export growth in the Global South economies has fallen by more than half the rate achieved prior to the Great Recession. And this measure includes China, the world’s largest exporting economy.

Source: CPD, MR calculations

World trade growth in the first quarter of 2023 now stands at -0.9%, following a decline of 2.0% in the final quarter of last year. Most regions showed a decline in merchandise trade during the most recent two quarters, signaling a further drop in goods trade, according to CPD. And now there is a global manufacturing recession.

Global manufacturing PMI (anything below 50 is recession).

Source: Trading Economics

The World Bank’s latest Global Economic Prospects paints a dire situation for many poorer economies. It says that the UN’s 2030 anti-poverty development goals are now “well off course”. The world’s poorest countries are expected to pay 35% more in debt interest bills this year to cover the extra cost of the Covid-19 pandemic and a dramatic rise in the price of food imports. More than an extra $100bn will be spent by the poorest 75 countries, many of them in sub-Saharan Africa, to cover loans taken out mostly over the past decade.

Debt payments are consuming more of government spending in poor countries when they were already struggling to provide education and health services. Wars and extreme weather events linked to the climate crisis are more likely to cause distress in low-income countries than elsewhere because of scanty social safety nets. On average, the poorest countries spend just 3% of GDP on their most vulnerable citizens – compared with an average of 26% for other economies.

Economic growth in developing economies other than China will fall from 4.1% in 2022 to 2.9% in 2023. World Bank chief economist Gill said: “By the end of 2024, per-capita income growth in about a third of EMDEs will be lower than it was on the eve of the pandemic. In low-income countries – especially the poorest – the damage is even larger: in about one-third of these countries, per capita incomes in 2024 will remain below 2019 levels by an average of 6%.” Fourteen low-income countries are already in, or at high risk of, debt distress, up from just six in 2015. As many as 21 countries are vulnerable.

Let’s just consider a few of those debt disasters.

Ghana has long been considered a success story and a model for African development. It is a major producer of gold and cocoa and has one of the region’s highest GDP per head. But the government has now been forced into a $3bn IMF bailout when it defaulted on its debts last December. The government borrowed heavily to insulate the economy from the effects of the pandemic. As a result, public sector debt went from 62% of GDP in 2020 to more than 100% last year. Debt servicing now takes up about 70% of government revenues.

Ghana found itself shut out of international debt markets as concerns grew over its ability to repay what it owed. Now, in order to get the IMF funds, domestic lenders ie local banks, must accept a loss on their loans. But Ghana also has to get foreign lenders to take a ‘haircut’ on the $34bn in debt and that won’t be easy. Private lenders are responsible for 60% of the face value of Ghana’s external debt, but the high interest rates they charge mean they are responsible for 75% of debt payments. These lenders won’t take any haircuts without a fight. The Ghanian government has stopped borrowing any more and is imposing severe spending cuts on public services, such as they are. Taxes are being hiked – but this will only affect those in ‘formal’ employment. Most people work ‘informally’ with cash and many companies evade tax altogether. Corruption is rife.

Nearby Nigeria is also deep in trouble. Africa’s largest country is riven with internal wars, endemic corruption and waste of energy revenues. Foreign direct investment has dropped to its lowest levels in nine years: from $3bn in 2015 to $468mn. An extra 13m Nigerians are predicted to fall below the poverty line between 2019 and 2025.

Lebanon is a country that still has no government a year after national elections, with only a caretaker administration in place, and has been without a president for seven months. The former central bank governor is accused of corruption, money laundering and embezzlement. The Lebanese pound has lost more than 98% of its value against the dollar since 2019, while annual inflation climbed to 269% in April.

Over in Asia, a hugely populated country (230m), Pakistan, is in a deep political and economic crisis and is now turning to the IMF for a bailout. The country has $126bn in external debt and must repay $80bn of this over the next three years. The rupee has lost 50% of its value compared to the US dollar. FX reserves to cover payments are down to just $4.5bn. GDP is falling. The country has been hit by earthquakes and floods and is being run by the military, which sucks up much of government spending. Inflation is at an all-time of high of 38%.

Then there is Argentina, one of the better-off ‘emerging’ economies. The economy is locked into chronic hyperinflation and debt. It has been forced yet again to go to the IMF for more funds to pay back what it already owes to it. The country faces big debt repayments this month and next.

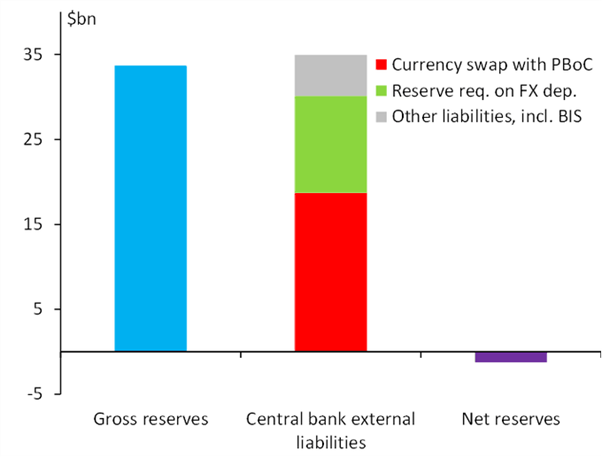

And FX reserves have run out. Argentina’s net reserves turned negative in May.

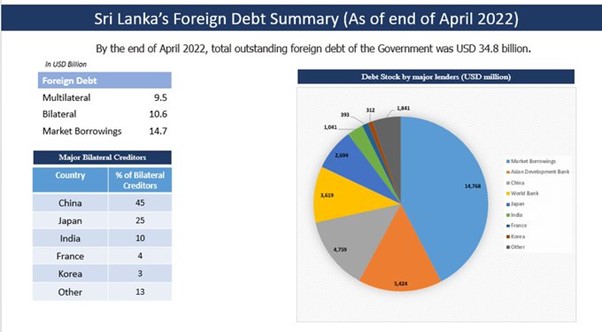

The Sri Lanka debt nightmare in 2021 culminated in mass protest and the fleeing of the then president from the country. But the debts remain. Much has been made of the debt owed to China, claiming that China is the problem by driving poor countries into a ‘debt trap’. But just 14% of Sri Lanka’s foreign debt is owed to China, while 43% is owed to private bondholders (largely Western vulture funds like BlackRock and banks like Britain’s HSBC and France’s Crédit Agricole). Another 16% is owed to the Asian Development Bank (over which the US has significant influence) and 10% is owed to the World Bank (dominated by the US as well). So “multilateral” debt really means debt owed to US-dominated institutions.

What is to be done? Clearly, the first immediate measure is to cancel the huge debts built up by these poor countries. The debts are the result of a weak world capitalist economy; corruption and mismanagement by local governments; and the rapacious squeeze on the resources and revenues by foreign lenders.

There is a significant concentration of holdings by a few major external creditors. Back in the 1990s the top-five external creditors accounted for 60% of total external credit to low-income countries and consisted mainly of multilateral and Paris Club creditors. As of end-2021, the concentration of the top-five external creditors had further increased, accounting for 75% of total external credit to LICs. And the share of debt owed to the private sector has approximately doubled from 8% to 19%. So if the IMF, World Bank and just a few key creditor countries agreed, the debts of the poor countries could be removed. Will the Paris meeting do anything about this? I doubt it.

Then there is the longer-term issue: the continual exploitation by the imperialist bloc, through their multi-national companies and financial institutions, of the labour of the Global South with the connivance of domestic corporations and governments of the local elite. Without a total restructuring of the world economy towards collective ownership and planning under workers governments, the debt misery will continue.

This system worked well while the Third World had enough resources to keep exporting commodities cheaply while, at the same time, maintaining “austerity” fiscal policies without stressing the IMF too much.

While it worked, the USD was kept relatively strong while USA could keep rising its twin debts at will; the fall of the USSR and the aggressive capitalist expansion to Eastern Europe (Warsaw Pact) and ex-USSR space also gave the American Empire a room for breathing and even a short period of trade surplus (during Bill Clinton’s reign, which I consider the apogee of the American Empire as laid down by FDR).

But, after the 2008 financial meltdown — which involved, some years before, a historic cyclical rise in commodities’ prices — this scheme clearly fell apart. For historians, the most interesting part is not that this global social contract fell, but how it lasted for so long (17 years) given how inherently unstable it is, and how, during its apex, people thought it would last forever.

Coincidentally, Germany has just announced its first ever National Security Strategy:

https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/germany-announces-first-national-security-strategy-2023-06-14/

Long story short, it declares Russia as its main enemy and China as its next main enemy; aims to continue to protect the “International Order”.

Scholz also announced Germany will soon prepare and publish a dedicated NSS for China.

It might just be the official claptrap they have to spew to the mainstream media. Historically, in times of crises, Germany – and now maybe France too – has always looked Eastward. Hence; the recent bullying from Poland and Greece, and the NATO exercices admittedly for deterrence purposes. According to a declassified document, the aims of NATO are twofold: to contain [Soviet] Russia and to contain a surge in German militarism, that is imperialism, which however has been allowed for the US.

I agree with Michael Hudson that the first enemy of the US is not China or Russia but Europe; there is fear this highly industrialised capacity starts looking to the East. Look up Rapallo treaty of 1922.

I think the death of Marxism in 1989 in the West left an enormous power vacuum in the ideological front that was quickly filled by countless dollar store analysts and ideologues. We now live in the golden age of the analyst and its more sophisticated iteration, the social media ideologue: contrary to what the Postmodernists were claiming, never before in the History of mankind we had so much ideology at such high and cheap supply.

My bet is, once the rise of China becomes really obvious to the vast majority of the world’s population, it will become equally clear we are in a 2nd Cold War (the End of History being only an interregnum, akin to the 1930s), and Marx’s theory of History will be demonstrated empirically once again. All of the chaff we read on the internet will become dust of History, like most Cold War publishing was.

When reviewing yet again how the large monopoly capitalist countries use foreign lending to extract flesh from middle- and low-income countries, the multi-polarista commentators get China wrong. However, China and the Western powers love to point a finger at the other guy, giving us useful information. Thus,

“According to our estimates, developing and emerging market sovereigns owe 370 billion USD to China compared to 246 billion USD in debt owed to the group of 22 Paris Club member governments.”

http://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w26050/w26050.pdf

The same study found that China keeps much more of its lending secret than the West.

“50% of Chinese overseas lending commitments are not recorded by the World Bank and thus do not enter officially reported debt statistics.”

China today is no more a friend of the working people in economically weak countries than are the Western powers. To be sure, the ruling elites in some of these countries have benefited greatly from selling out to China instead.

If the multipolar world is to result in a “Chinese imperialism”, then it will be a very different kind of imperialism than the imperialism we know it today, since the 1980s-1990s, because China’s pattern of credit offering tend to increase the OCCs of the Third World countries it lends to, not decrease. The pattern of credit offering of the IMF/US Treasury was/is tended/tend to go the opposite direction, i.e. to lower the OCCs of the Third World it lends to.

My guess for this pattern 180º reversal is that, because China is a socialist nation, its impulse of expansion (which, in the context of modes of production, are always motivated by the self-preservation of said mode of production, of itself) manifests as the promotion of the development of the productive forces. Since the 1990s, capitalism has been in its negative phase (i.e. “late capitalism”), and it was already global, so its pattern of lending was in the direction to “turn back the clock”, i.e. undevelop the productive forces.

Capitalism can only promote the development of the productive forces in relation to the old it overcame, i.e. feudalism, never in relation to socialism, which is its immanent successor and, therefore, its superior.

Hi Charles1848,

I have scanned the document you link but did not come across any of the terms of the loans. Do Chinese loans handcuff recipients towards austerity? Do they require eliminating/privatizing public services? If the answer to these questions is ‘yes’ then I believe your comment about its relationship to the working class is valid. If not, then I think you will need to rethink your final statement.

High interest rates, importing workers from China on work locals could do, siphoning off revenue once a railway goes operational, mining with disregard for the environment … there are many ways China’s capitalist investments in less-developed countries cause harm. Not the place here to debate it out. The point was simply to note that China is as involved in the “developing debt disaster” as the Western monopoly capitalists.

Yes, it seems China is as much caught up in the (government) ‘debt and deficit’ dogma as the West.

What to do about China’s falling exports to the West which is facing recession while fighting inflation, and the consequent loss of employment in “the world’s factory” in China?

It seems China doesn’t think it can resort to its old playbook of rolling-out infrastructure, as it did during the GFC, because China now has a much higher national debt – which seems to be worrying Chinese economists, judging from articles in ‘the Global Times”.

They need to speak to Prof Steve Keen:

Building a New Economics

“Money from Nothing: If everyone could accept this basic accounting truth, capitalism would function a lot better.”

https://profstevekeen.substack.com/p/money-from-nothing?utm_source=post-email-title&publication_id=872467&post_id=128010491&isFreemail=false&utm_medium=email

Xi – and PBofC execs – barely undertand why Evergrande collapsed, and are still trying to stimulate a moribund private housing sector via manipulating interest rates, whereas he should be building public housing for everyone who doesn’t have a house. He did confirm: “Houses are for living in , not investment vehicles”.

this 50% is like standard assumption because ISS (which gives miltirary budget & other rankings, in stockholm i thnk) considers china’s defence 50% more than what is declared.

https://profstevekeen.substack.com/p/money-from-nothing?utm_source=post-email-title&publication_id=872467&post_id=128010491&isFreemail=false&utm_medium=email

Building a New Economics

“Money from Nothing: If everyone could accept this basic accounting truth, capitalism would function a lot better.”

STEVE KEEN

………………….

‘Socialist’ production is old-fashioned anyway; with increasing AI, IT and automation, we need the public sector to take more direct control of money creation, as Keen says.

“Money from nothing” buys nothing. It’s a pirate’s “socialism”.

“‘Socialist’ production is old-fashioned anyway; with increasing AI, IT and automation,”

What’s even more old fashioned is bourgeois production, wasteful, planet destroying production based upon the parasitism of a tiny privileged class at the expense of the vast majority of humanity, the proletariat, who live lives of drudgery and misery in order to make the lives of privileged first-world bourgeois individuals like yourself possible. You can fantasize about capitalist production surviving until the end of time all you want but Marx was just as correct 150 years ago as he is now, the end of capitalism is inevitable, the victory of the proletariat over their exploiters is inevitable, capitalism is just one tiny step in the evolution of human society from an agglomeration of brutish egoist (as in class society) to the realization of man’s Communist Species Being.

”Therefore, neither the government nor the banks needs a stock of anything—gold, flowers, chairs, or anything else—before they create money. What they do need are people with whom they can have a financial relationship: taxpayers for the government, borrowers for the banks. Borrowers have to agree to go into debt; taxpayers simply have to be subjects of a given government, in which case they are recipients of government spending, and liable to pay taxation.”But how can governments spend before they tax. As Adam Smith pointed out money is command over others’ labour. Unless people work and create value, they cannot be taxed. Nihil exnihilo!

“we need the public sector to take more direct control of money creation, as Keen says.”

Who is this “we”? “Needs” according to which (historically conditioned) class perspective? The “needs” of the bourgeoisie and their ideological hangers-on are vastly different than the needs of the (advanced, class conscious) proletariat who above all else “need” to abolish the bourgeoisie and all of the bourgeois economic categories and ideas uncritically accepted by you and Keen as “self evident”, along with the bourgeois institutions that weaponize these bourgeois ideas against the proletariat.

Au contraire, only socialized production can properly utilize automation and artificial intelligence (the mechanization of those roles assigned to professional “intellectuals” under the bourgeois division of labour, which it should be noted marks the final nail in the coffin for the bourgeoisie’s historical justification) in a way that can even begin to unleash their potential. It is the bourgeois mode of production that is hopelessly old-fashioned. It will soon collapse or rather the working-class will soon “collapse” it. The capitalist mode of production if finished.

@Charles1848

The Chinese don’t give two hoots what Western based ‘socialists’ (an infantile disorder?) think about them. Why should they?….look what you’ve allowed to happen in your own backyards post millennium.

Don’t even get me started on the Uncle Sambo led Collective Waste’s non stop global permanent war mongering, fascist coup sponsoring, economic starvation sanctioning and trade embargoing.

A Chinese property developer, mining (the West didn’t have a 200 year head start on industrialisation- no environmental damage there?)…Chinese workers stealing jobs!!! (sound like the BNP).

The workers of the Global South?….what’s happened to the working class in the ‘civilised’ west?

Lenin was right.

Don’t worry about the Chinese (they’re certainly not worried about you, that’s not their job), worry about the behaviour and actions of your own ruling, political and media class.

Is it possible to introduce a resolution in UNGA about abolishing all debts to countries that are poor ? it must be done every year like with the resolution against US embargo on Cuba?