The Russian invasion of Ukraine grinds agonisingly on with more dying and displaced and with further destruction of Ukrainian cities, farms and homes. Back in the major economies, there is another war brewing: the war on inflation.

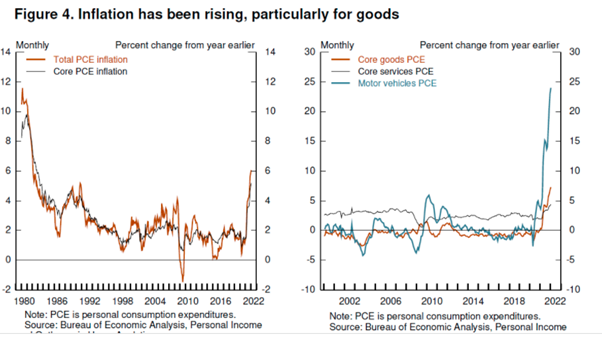

Inflation of consumer prices are now at 30-40 year highs with more to come. The COVID pandemic slump and now the Ukraine conflict has driven energy and food prices up to record highs. The war in Ukraine has gone global. Spiking commodity prices are on track to see their sharpest rises since 1970, sending a shock wave of suffering across the world as the prices of essential goods every human needs to survive are surging upwards. Wheat prices are up 60% since February. Food prices are now higher than during the global food crisis of 2008, which pushed 155 million people into extreme poverty.

And the price inflation in these key areas has migrated into general price increase. Annual consumer price inflation (CPI) now stands at 7.9% in the US, 5.9% in the Eurozone; 6.2% in the UK and even Japan, long a deflating economy, now has an inflation rate of 1%. In the so-called emerging economies, inflation is even worse: India 6.1%; Russia 9.2%; Brazil 10.5%;, Argentina 52%; Turkey 54%.

The battle is now to reduce and control inflation and it is being led by the central banks of the major economies: the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, the Bank of England and the Bank of Japan. It is the primary job of central banks to control price inflation; not to help to sustain employment and economic growth – they are secondary. (“The ultimate responsibility for price stability rests with the Federal Reserve” – Jay Powell). That’s because inflation is the main enemy of the banking system. Creditors and lenders of money lose out if inflation rises, while debtors and borrowers gain. And central banks were created to support the financial sector and its profitability and not much else.

And indeed, there is not much else they can do. I have shown in many previous posts the evidence that central banks have little control over the ‘real economy’ in capitalist economies and that includes any inflation of prices in goods or services. For the 30 years of general price disinflation (where price rises slow or even deflate), central banks have struggled to meet their usual 2% annual inflation target with their usual weapons of interest rates and monetary injections. And it will be the same story in trying this time to reduce inflation rates.

All the central banks were caught napping as inflation rates soared. And why was this? In general, because the capitalist mode of production does not move in a steady, harmonious and planned way but instead in a jerky, uneven and anarchic manner, of booms and slumps. But specifically now, because as Fed Chair Jerome Powell put it in a keynote speech to the National Association of Business Economists last week, “Why have forecasts been so far off? In my view, an important part of the explanation is that forecasters widely underestimated the severity and persistence of supply-side frictions, which, when combined with strong demand, especially for durable goods, produced surprisingly high inflation.” Indeed, I have argued in previous posts that, contrary to the view of the Keynesians, the current inflation burst is not due to ‘excessive demand’ or ‘excessive wage increases’ (cost push), but due to the failure of supply/production.

As Powell put it: “contrary to expectations, COVID has not gone away with the arrival of vaccines. In fact, we are now headed once again into more COVID-related supply disruptions from China. It continues to seem likely that hoped-for supply-side healing will come over time as the world ultimately settles into some new normal, but the timing and scope of that relief are highly uncertain.” And this poses an intractable problem for the central bankers in their quest to protect bank profits. Their monetary weapons will prove useless in this war on inflation. Powell said that “We have the necessary tools, and we will use them to restore price stability.” But does he? As Andrew Bailey, governor of the Bank of England, said: “Monetary policy will not increase the supply of semiconductor chips, it will not increase the amount of wind (no, really), and nor will it produce more HGV drivers.” And Jean Boivin, a former Bank of Canada deputy governor now at the BlackRock Investment Institute, commented: “We are not dealing with demand-push inflation. What we are really going through right now is a massive supply shock and the way to deal with this is not as straightforward as just dealing with inflation.”

If rising inflation is being driven by a weak supply-side rather than an excessively strong demand side, monetary policy won’t work. Monetary policy supposedly works by trying to raise or lower ‘aggregate demand’, to use the Keynesian category. If spending is growing too fast for production to meet it and so generating inflation, higher interest rates supposedly dampen the willingness of companies and households to consume or invest by increasing the cost of borrowing. But even if this theory were correct (and the evidence does not support it much), it does not apply when prices are rising because supply chains have broken, energy prices are increasing or there are labour shortages.

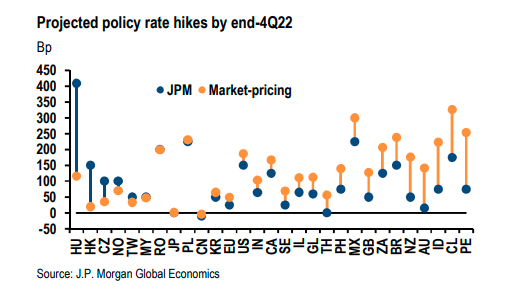

Nevertheless, central banks have only the monetary weapon to apply to accelerating inflation. So the Fed plans a sharp rise in its ‘policy rate’ of interest (the Fed Funds rate), which sets the floor for all borrowing in capitalist markets. And so do other central banks.

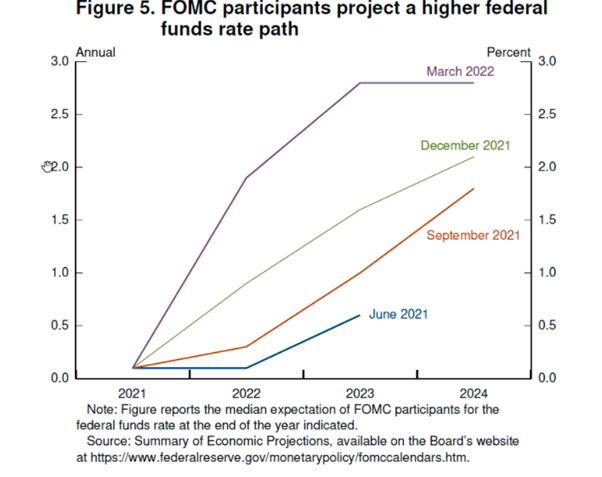

Powell aims to hike the Federal funds rate to 1.9 percent by the end of this year and thus rising above its estimated longer-run normal value by 2023.

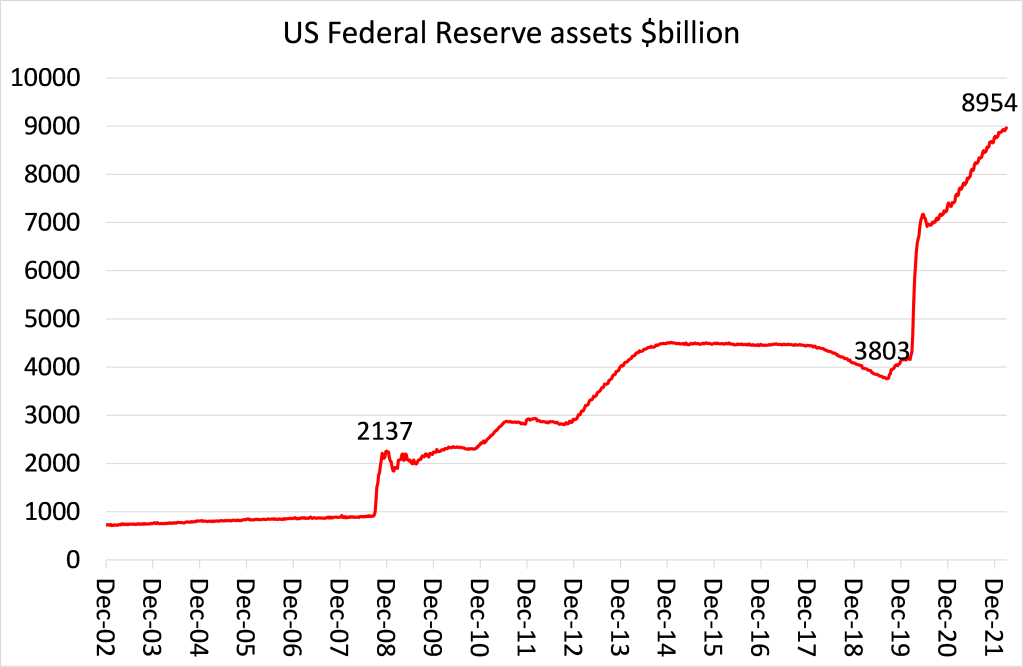

At the same time, the Fed is ‘pivoting’ on its previous programme of ‘quantitative easing’ (QE) ie buying government and government-backed bonds through an increase in money supply. During the 21st century, the Fed has bought so much government paper that its balance sheet has jumped from $1 trillion to nearly $9 trillion, more than doubling during the COVID pandemic.

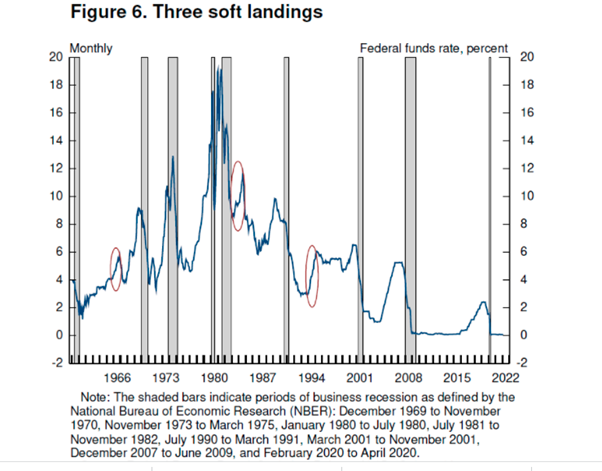

Now the Fed is going to reduce the total amount of the balance sheet. Powell claims that “these policy actions and those to come will help bring inflation down near 2 percent over the next 3 years.” Indeed, there is optimism in mainstream economics that increased interest rates and a reverse of monetary injections by the Fed and other central banks will not only kill inflation but also avoid a slump in investment and consumption as a result, as long the Fed gets on with the war on inflation and ends its policy of appeasement. Powell commented that “the historical record provides some grounds for optimism: Soft, or at least soft-ish, landings have been relatively common in U.S. monetary history.5 In three episodes—in 1965, 1984, and 1994—the Fed raised the federal funds rate significantly in response to perceived overheating without precipitating a recession.”

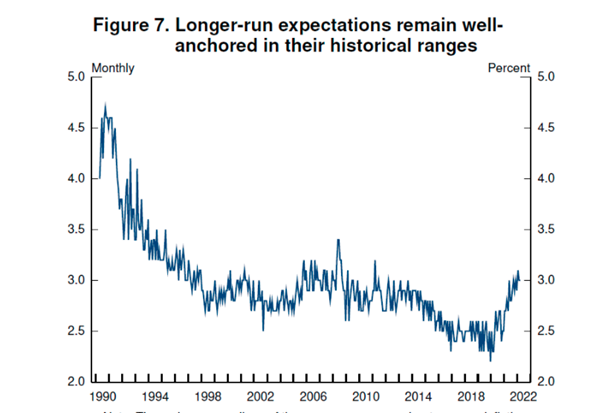

Powell also made much of the current mainstream explanation of inflation: that it is mainly caused by ‘expectations’ of price rises gaining traction among consumers and businesses – self-fulfilling if you like. “In the recent period, short-term inflation expectations have, of course, risen with inflation, but longer-run expectations remain well anchored in their historical ranges.”

This ‘psychological’ explanation of inflation removes any objective analysis of price formation. Why should ‘expectations’ rise or fall in the first place? And as I mentioned before, the evidence supporting the role of ‘expectations’ is weak. As a new paper by Jeremy Rudd at the Federal Reserve concludes; “Economists and economic policymakers believe that households’ and firms’ expectations of future inflation are a key determinant of actual inflation. A review of the relevant theoretical and empirical literature suggests that this belief rests on extremely shaky foundations, and a case is made that adhering to it uncritically could easily lead to serious policy errors.”

Powell significantly left out of his ‘soft recessions’ the two deepest and widest slumps in the major capitalist economies since 1945, namely 1980-82 and the Great Recession of 2008-9, when interest rates rose sharply prior to the start of recession. In doing so, he cannot offer an explanation of why tighter monetary policy can have ‘soft’ landings sometimes and slumps other times.

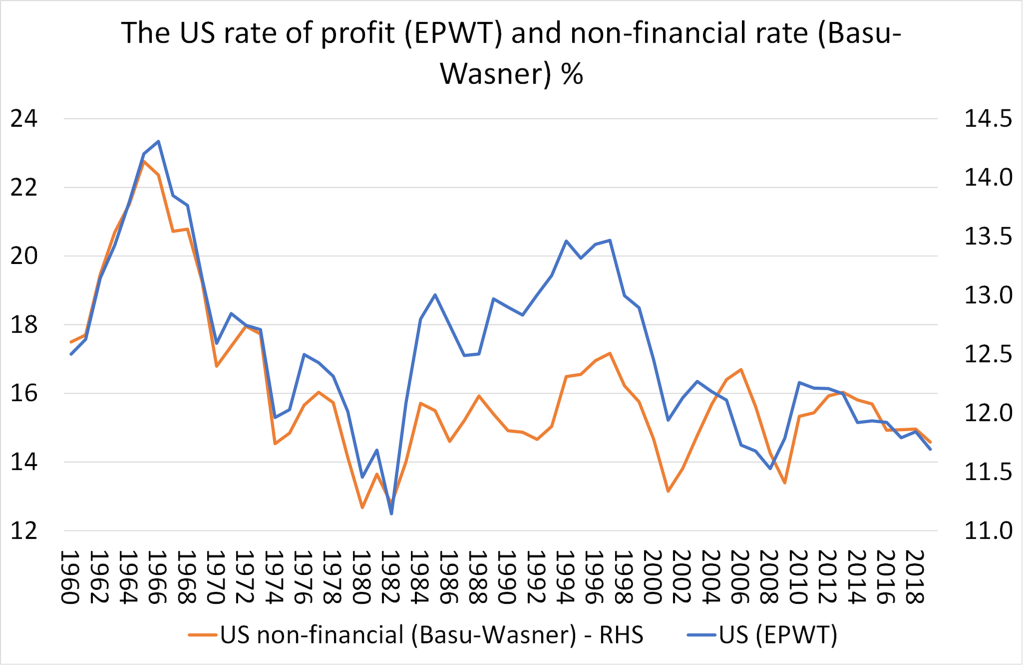

What is missing from any explanation are two things that Marxist theory offers. First, what is happening to the profitability of capital; and second, what is happening to the real rate of interest (after taking into account the inflation rate). In periods where average profitability is high and/or rising, then interest rates can and will rise too but without crushing investment (both productive and unproductive (real estate and finance). That was the case in all the ‘soft’ landing cases cited by Powell.

It was also the case in another optimistic argument for the likely success of monetary policy in controlling inflation. One analyst claims that 1946-48 period is the best historical parallel to now. There were serious supply shortages then leading to sharp rises in price inflation. But eventually price increases slowed as supply came on board as manufacturing switched from military to civil production. The Fed did not have to hike interest rates but just applied a relatively mild reduction in credit growth to shrink its balance sheet. In other words, the market’s “invisible hand” worked. But this explanation again fails to note that average profitability of capital in this period was at 20th century highs, with labour cheap and unused technology to be applied. No wonder supply came on board quickly to douse the flames of inflation.

But that was not the situation in 1980, after the huge profitability crisis that began from the mid-1960s and was exacerbated by the international slump of 1974-5. And it was not that case in 2008-9, where the profitability of productive capital was not much higher than in the early 1980s and much lower than in the 1946-64 ‘golden age’ of capitalist production or even the ‘neo-liberal’ recovery period of the 1980s and 1990s.

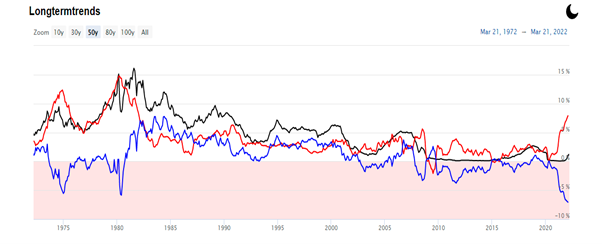

Then there is the second factor, the real rate of interest. Paul Volcker became head of the Federal Reserve in 1979 when inflation rates, triggered by high oil prices and tight labour markets capping supply adjustment (unlike 1948), had reached 20th century highs. Volcker, a convinced ‘monetarist’ and strong advocate of the interests of bankers, immediately hiked interest rates to such levels that real Fed fund interest rate jumped from -3% to +5%. You can see that jump in the graph below, where the red line in the US CPI inflation rate, the black line is the Fed Funds nominal rate and the real rate is the blue line.

This shock hit to borrowing costs in real terms coupled with the very low profitability of capital caused the deepest post-war slump for the major capitalist economies, in two bouts over three years. It was the end of manufacturing jobs in the US, Western Europe and the UK. Productive capital moved to Eastern Europe, Latin America and Asia. Indeed, it was this slump that killed inflation and brought down oil prices, not rising interest rates.

What is the current situation for the real rate of interest? It is even lower than when Volcker took over in 1979. Two things flow from that: to do a ‘Volcker’ and take the Fed real rate into positive territory in order to curb inflation would require a series of Fed hikes not matched in 100 years; and if that were to be applied, given the near post-war low in profitability, it would almost certainly deliver a new slump in investment and production in the major economies – let alone its impact on the so-called emerging economies of the Global South.. All this tells you that monetary policy is a crude weapon to control inflation and is not going to succeed without causing a major slump – no ‘soft’ landing.

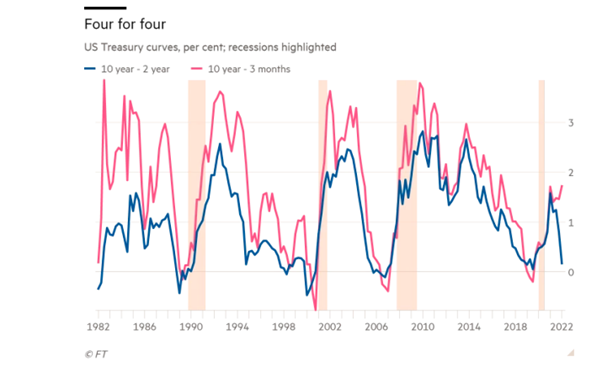

One useful indicator of a recession in the past, which I have mentioned before, is an inverted yield curve. That’s when, in the bond market, the rate of interest or yield on a short-term loan (3m or 2yr) rises above the rate of interest or yield on a longer-term loan or bond (10yr). Normally, if you borrow (issue a bond) for a longer period you must pay a higher rate of interest to the lender or purchaser of the bond because the length of time for the credit is longer and so the loan is subject to more inflation or default risk. But when the ‘yield curve’ flattens or even inverts, a recession usually follows. Why? Because it tells you that purchasers of bonds are getting worried that interest rate hikes will cause a possible slump and so are buying more safe long-term government bonds to protect their cash.

Well, currently the US government bond yield curve is fast heading towards inversion. Jay Powell’s hawkish speech declaring war on inflation led to a sharp drop in the curve. The blue line in the graph below, the 10-year/2-year curve, is barrelling straight towards zero. In the past 40 years, every time that has happened, a recession has followed (as the shaded bits of the chart show). In fact, it’s worse than that: inverted 10/2 curves have preceded the last eight recessions and 10 out of the last 13 recessions, according to Bank of America.

Powell tried to dismiss the yield curve indicator in his speech to the NAB, arguing that only the short end of the curve was an indicator of recession and that is when it is falling, not rising: “there is good research by staff in the Federal Reserve system that really says to look at the short — the first 18 months — of the yield curve. That’s really what has 100 per cent of the explanatory power of the yield curve. It makes sense. Because if it’s inverted, that means the Fed’s going to cut, which means the economy is weak.”

Whatever the predictive value of the bond yield curve, the point is that the US economy, the best performer among the G7, is set to slow as the year progresses. There is little room for any further growth through employing more workers, while productivity and business investment is slowing. Year-on-year nonfarm business sector labour productivity advanced only 1% at the end of 2021, down compared with 2.4% in 2020. And business investment was only just 2.4% above pre-pandemic levels at end-2021. Several forecasts now suggest a significant slowdown in economic growth in the US and the UK, and probably an outright recession in the Eurozone before the year is out.

And it is not just the productive sectors of the economy that are at risk. It was the collapse in the housing sector in 2008 that triggered the Great Recession. And after a massive real estate spree during the COVID pandemic, if mortgage rates rise sharply, house prices could turn down, weakening consumer spending. US bond investor Bill Gross commented “I suspect you can’t get above 2.5 to 3 per cent before you crack the economy again. We’ve just gotten used to lower and lower rates and anything much higher will break the housing market.” Mortgage debt as a share of real GDP has already risen 6 percentage points to 55 per cent since the last rate-hiking cycle peaked in late 2015.

Instead of a ‘soft landing’ as Jay Powell hopes for, Goldman Sachs analyst Philipp Hilderbrand reckons: “Stagflation risk is a real concern today… We are looking at a supply shock layered on top of a supply shock. And the nature of the new supply shock-centred on energy—suggests not only that inflation will move even higher and likely prove more persistent moving forward, but also that growth will take a hit.”

There is an alternative to monetary policy. It is to boost investment and production through public investment. That would solve the supply shock. But sufficient public investment to do that would require significant control of the major sectors of the economy, particularly energy and agriculture; and coordinated action globally. That is currently a pipedream. Instead, governments are looking to cut back investment in productive sectors and boost military spending to fight the war against Russia (and China next).

Which way will it go? Will Powell, Lagarde and Bailey be mini-Volckers or will they step back from the conflict and opt for fewer rate hikes and be forced to live with higher inflation? Either way, it suggests that inflation globally will not subside until a new slump emerges, signalling that the central bank war on inflation has been lost.

In the last paragraph I think you mean Lagarde instead of Draghi.

Whoops getting old!

“It is to boost investment and production through public investment. That would solve the supply shock. But sufficient public investment to do that would require significant control of the major sectors of the economy, particularly energy and agriculture; and coordinated action globally.”

Unless you’re talking about socialism, that wouldn’t work.

Public investment only works when guided by a sociometabolic plan. Just blind governmental investment (the proverbial “one company to dig holes, the other one to fill them”) would not be develop the productive forces, therefore would not configure investment.

So either you have full-fledged socialism, where the economy is centrally planned by the State itself – in which case everything that fall into the plan is an investment – or, in the case of capitalism, the government is ancillary to private guidance (i.e. of the capitalist class). In other words, public investment can, by definition, never be the main engine of capitalist reproduction (even in wartime command economy times, the industrial capitalists have a seat alongside the head of state in the whole of deliberative councilors or its equivalent, serving under the fiction of “saving the capitalists from themselves”, as was the case of FDR’s USA and Hitler’s Germany).

This logic is also applicable to older economic systems. For example, in Feudalism, the English king/queen (i.e. the Feudal State) had to develop an efficient tax collecting machine against the feudal lords class’ own will in order to safeguard English feudalism in the concrete form of a powerful navy because, by geographical accident, Britain happened to be an island.

The State never exists in abstract, it always has a qualification, e.g. capitalist state, feudal state, ancient state, socialist state etc. etc. To simply call for the State/public/government to come and save the day is fall into the statecraftist fallacy, and/or into the fallacy of Anglo-Saxon Empiricism (in opposition to German Historicism).

How about Italian Gramsci-Lariola concept of the State?

Althusser also has few words on State’s Ideological and Oppressive Apparatuses.

The “traditions” you referred to are so puny, shallow and cheap.

Mostly of the Uncle Joe’s “Popular Front” variety.

A bit more of theories of State, this one a sort of a conversation between Greece and Italy!

Neither an Instrument nor a Fortress

Poulantzas’s Theory of the State and his Dialogue with Gramsci

Peter Thomas has written an important book that brings forward the full importance of Gramsci’s strategic concepts and the pertinence they have for current theoretical and political debates. Based upon this interpretation of Gramsci, this text attempts a critical reading of the contradictory stance of the Althusserian School towards his work. Using Althusser’s own ambivalence towards Gramsci as a starting-point, the main aim of this article is to reconstruct Poulantzas’s direct and indirect dialogue with Gramsci. Despite Poulantzas’s reservations and criticisms regarding aspects of Gramsci’s work, his theoretical endeavour not only is indebted to Gramsci, but also represents, despite its shortcomings and limits, one of the more original and profound theoretical attempts to come to terms with the theoretical challenges posed by Gramsci’s elaboration on hegemony, hegemonic apparatuses and the ‘integral state’.

https://brill.com/view/journals/hima/22/2/article-p135_7.xml

I’m just waiting for the price of labour power to inflate. Waiting…..waiting….. If the prices of all other commodities increase, why not labour power? Could it be that by increasing the price of commodities other than labour power, the owners of the collective product of labour and natural resources will be able to achieve a higher rate of profit?

Price of labor power only automatically rises through its scarcity in the feudal system (Malthusian Cycle).

In capitalism, labor power must always fall in value terms. That’s because capitalism has something feudalism didn’t have: systematic automation (i.e. less workers are needed to produce more than ever; the generation of misery as the generation of wealth).

Not sure about “inflating” the price of labor power.

But increasing wages & benefits are a central aim & demand of workers organizing in Starbucks, Amazon, Uber,….

Amazon supermarket workers (on the West coast) are demanding $25 an hour, plus discounts same as Whole Foods, and access to all throwaway food.

And more health benefits, of course.

I find it surprising to waste time with interest rate estimates varying by 0.25% when political uncertainties could lead to crises that are far deeper than anything anticipated.

“But sufficient public investment to do that would require significant control of the major sectors of the economy, particularly energy and agriculture; and coordinated action globally. That is currently a pipedream. ”

Perhaps climate change will become destructive enough to dispel the pipedream.

Then global communism informed by MMT – which teaches us *resource mobilization”, not money, is the issue for currency issuing governments – will at last be established in a war-free world.

I retired as a teacher a long time ago. My wife, also a retired public servant is retired. Of course, inflation has reduced the real worth of our retirement income by at least half. Same for social security. But we live comfortably enough because we own the home we bought 35 years ago. Faux chique but cheap million dollar+ town houses keep going up all over the city (Sacramento, California). I could buy one if I sold my 100 year old cottage and took out a $200,000 mortgage that would break my negative interest piggy bank. I’m one of the last of the generation of decently paid workers of the golden years of war capitalism. Who will buy all these dollar bloated new empty dwellings? Certainly no one among the 90 percent of Americans who don’t have even the income or wealth that I enjoy. They are either homeless or have to make do on credit card peonage. Is the largess of mmt a solution to the hollow dollar inflated obesity of the US war on labor economy? Maybe. But it will amount to no more than Claus Schwab’s promise that the recipients will “own nothing, and be happy”–but not in your “free”, but in a war-ravaged, privately owned world.

Oops! it looks my wife retired twice! But she is very much alive… retired public servant.

That can’t and won’t happen because MMT is not a scientific valid theory.

“Then global communism informed by MMT – which teaches us *resource mobilization”, not money, is the issue for currency issuing governments – will at last be established in a war-free world.”

There is no money in a communist society. One of the first steps of communism is to abolish private property (of which money is a category). Communism will most likely use a system of labor accounting/labor vouchers for administration and distribution.

The first paragraph has a comparison with the 70’s.

And the last paragraph mentioned a slump, which all reminded me of:

:

:The Second Slump”

by Ernest Mandel

Named by Choice as an ‘Academic Book of the Year’ for 1979, The Second Slump locates the 1970s recession in the context of the theory and history of capitalist crises. It argues that the slump, unlike the earlier one in 1929-32, is marked by a high level of organization by the working class in the developed capitalist countries, and that it is fundamentally a crisis of over-production, in which oil price rises play only a secondary role.

https://www.versobooks.com/books/2632-the-second-slump

A compare and contrast study with the 70’s sounds extremely boring, but would be incredibly useful.

BTW, what is that “EPWT” after the US Rate of Profit.

Also, “Mortgage debt as a share of real GDP has already risen 6 percentage points to 55 per cent since the last rate-hiking cycle peaked in late 2015.”???

Elaborate, please.

EWPT is Extended World Penn Tables – a database that I have mentioned and used before. Mortgage debt to GDP in the US has risen in the last five years so that any interest rate rise now will do more damage than before.

Two of your points need emphasising. February retail sales in real terms have fallen by 19% and 16% from their March high depending on whether one uses 2 month or 3 month moving averages. The graphs can be seen in my article “Globalisation Tears Apart, Profits Bleed”. They have fallen back to 2019 levels as confirmed by the survey group BDM https://www.npd.com/news/press-releases/2022/consumers-pull-back-on-purchasing-as-retail-prices-remain-elevated-reports-npd/ So inflation is no longer driven by demand as you say, but by gaming the system. Secondly, we do need to keep an eagle eye on the US housing market. Pending house sales were expected to rise 0.9% in February after a fall of 5.7% in January only to fall by 4.1%. Median house prices also fell by 6.3% from the previous month reducing the annual increase to 10.7% and heading for a real fall. All this is consistent with 30-year mortgage rates trending above 4.5%.

It is for this reason that we should avoid focusing exclusively on the rate of profit. The two blades cutting the economic artery are falling rates of profit intersecting with rising rates of interest. If the US economy was a high wire act in 2008, now it is more like jumping out of a plane that has run out of sky without a parachute. Much worse.

No. Your premise is wrong: the system was always “gamed”, it just happens that, nowadays, it is gamed more. The explanation for that can only be the falling profit rates.

Besides, the USA is more and more disposable to the capitalist system: just using U.S. data distorts analysis of reality. The USA is not the alpha and omega to the capitalist system it was during the Cold War.

We should focus more than ever on the rate of profit, that is, the polar opposite of what you propose.

Correction: the real term falls in US retails sales based on trends: “the two-month trend sales are down 20% from their March 2021 high, and on the basis of the three-month trend, they are down 14%.”

This is a really excellent article.

There are two things that I am curious about. When you discuss trying to raise or lower ‘aggregate demand’, you say that “even if this theory were correct (and the evidence does not support it much) (…).” I am interested in ‘the evidence does not support it much’ – would it be possible for you to elaborate on this fundamental point? I know that some years back, you wrote an article on the multiplier, but I do not find it back. And towards the end you write that sufficient public investment would require significant control of the major sectors of the economy, particularly energy and agriculture. Why agriculture? I do not understand.

Best regards, Dordi

Hi Dordi just search on my blog for aggregate demand, or consumption or multipliers etc. I added agriculture because without control and ownership of the large international food producers and processors, the fertiliser companies and latifundia landlords, food supply will not reach the poorest and will be sold at ludicrous prices.

This is an answer coming from France, made with automatic translation, after some long discusion going on for years on the importance of Central Banks, between comrades.

War in Ukraine: Central Banks at war with inflation? Really???

Monday 28 March 2022, by Luniterre

In a new exchange with comrade Viriato, a proposed response to Michael Roberts’ recent article which tends to undermine the role of the Central Banks in the current crisis.

The original article by Michael Roberts on the author’s website:

https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2022/03/26/the-war-on-inflation/

The translation proposed by comrade Viriato:

Click to access Michael-Roberts-La-guerre-des-Banques-Centrales-contre-l-inflation.pdf

For Michael Roberts the “expectations” of inflation made by the major Central Banks, and mainly by the FED, would necessarily be wrong because this inflation is due to the “supply shock”, i.e. the various shortages generated successively by the so-called Covid crisis and by the war in Ukraine.

This article by Roberts is very accurate on one point: we must indeed distinguish the current situation of “supply shock” from a classic “Trente Glorieuses” type of inflation, based on a good return on capital, and still growing, until the mid-1970s.

In reality, it was as soon as the first “oil shock” in 1973 that the really productive industry started to migrate to the South-East Asian countries. But the overall profitability of capital continued to grow for some time, notably with the rise of the Chinese export industry.

What Roberts does not distinguish sufficiently, especially for a supposed “marxist”, is the difference between the cyclical causes and the fundamental causes, linked to the technological evolution of the industrial production tool. It is the expansion of the industrial proletariat that allows the expansion of capital, and vice versa, with automation and robotisation.

This evolution is itself differentiated according to the level of development of the countries, but it necessarily follows the same curve for each industrial development basin and moving the bulk of productive investments only shifts the problem without solving it, and if it seems to delay, in the short and medium term, the deadline of the fall of profitability of capital, it actually hastens it, globally, by accelerating the process in the countries where investment is massive.

This process is therefore not strictly linked to cyclical crises, even if there is obviously a strong interaction between the two, cyclical conditions and the acceleration of the process.

Although productivity peaked in Europe and Japan at the turn of the 1970s, the fall has been global and constant since then, with no significant rebounds. The “oil shock” is not the cause, but simply the “indicator”, in terms of symptoms.

(The graphic is missing but can be found with the link just after. I just don’t know how to show it…)

China began, at that time, its accelerated upward curve, due to two concomitant factors:

The main one being its complete backwardness.

The “engine” being its transformation into an export industry “sponsored” by foreign, mainly US, capital. Now China has also passed its peak of profitability, even if it can “surf” for quite a long time on the top of its own wave, effectively helped in this by the international “conjuncture”.

It is therefore essential to distinguish the problem of the supply shock from the problem of the intrinsic profitability of the industrial tool, zone by zone!

Without omitting to analyze the interactions, obviously, but this is what is seriously lacking in Michael Roberts’ analysis, one of his “best”, albeit in a relative sense.

This distinction between the “cyclical” and the “fundamental” is therefore also to be made in the analysis of the monetary policies of the Central Banks.

Everything that currently comes out of the “control” or not of inflation remains cyclical, contrary to what Roberts thinks. Moreover, the financial markets have already “absorbed” the shock of the war in Ukraine.

In the global economy, this war is only delaying the return to deflationary fundamentals in modern industry. It is thus, in the short term, completely integrable in the strategy of the Central Banks, which created the inflationary plaster of Covid to let the financial capital continue to walk on this wooden leg the time to advance their structural reforms in depth of the system of class domination. A subject that completely escapes Roberts’ ‘analysis’.

What “bothers” the Central Banks more, on the contrary, in case of a Russian victory, is the enlargement, at the very heart of the planet, in terms of geo-economic centres, of a non-bank-centralised economic development zone, based on a set of exchanges and partnerships between national bourgeoisies, such as Russia, Iran, etc…

The three countries grouped together in the heart of Europe, Russia, Belarus and Ukraine, with their respective resources and capacities, could potentially turn the balance of power on a global scale on its head, with this third pole likely to generate an endogenous dynamic escaping the grip of the five major Central Banks (FED, ECB, PBoC, BoE, BoJ) and even, to a large extent, the grip of speculative financial capital, insofar as the industries of these countries remain under relative national state control.

This is why, in the absence of the rebirth of a workers’ movement in the West, and for good reason, it is necessary to support this group in the process of formation, without obviously cultivating the slightest illusion about its “proletarian” nature. At least it will manage, for a few more decades, to slow down the process of decline of the industrial proletariat and to allow the social movement to regain both the breath of reflection and, while we’re at it, that of action!

Here, in a nutshell, is the point of the current situation, as we can understand it, according to the criteria chosen, and relatively well seen, otherwise, by Roberts.

To go into a bit of “technical” detail, we must understand that the situation of the rouble is very different from that of the yuan, on the world money market.

The rouble is apparently a very weak currency, in relation to the small weight of the Russian economy on a global scale (GDP equivalent to that of Italy), but which nevertheless circulates at its true market value, contrary to the Chinese yuan, which necessarily has a forced banco-centralized rate (the famous “pivot rate”!), because of the volume of trade with the USA and the interdependence that remains between the two countries’ capitals.

Even if China buys oil in yuan from Saudi Arabia, for example, this does not reduce its dependence on its industrial exports to the “dollarized” West. It is, at best, a very relative gain in independence for Saudi Arabia, but it still has to find an advantageous use for this yuan reserve.

So the “de-dollarization” through this kind of transaction is still derisory at the moment.

It should be noted that the “Silk Roads” project, insofar as it is based on long-term Chinese credits, does not necessarily lead quickly to the autonomy of Chinese foreign trade in relation to the “dollarized” world, which would be necessary to make the yuan a real reserve currency competing with the dollar.

The project is only possible as long as China can finance it with the surpluses of its foreign trade with the “dollarized” countries of the West. Its long-term profitability is therefore not at all obvious, and it leads China more towards banco-centralism than towards the profitable imperialist expansion it has been pursuing since the beginning of the 21st century.

The Russian economy, by contrast, relies heavily on the export of raw materials, but has otherwise been rebuilt relatively endogenously, out of necessity, by international sanctions. So if the sale of its raw materials is now largely done in rubles, the gain is direct, both for the currency and for the economy, and constitutes a real “de-dollarization” directly evaluated on the money market, and tends, if Russia wins, to make the ruble a real new international reserve currency, unlike the yuan, which will still remain for a long time dependent on its “central rate”, i.e. its de facto parity with the dollar!

With Putin’s initiative, what was Russia’s weakness yesterday is now its strength. Provided that the military operation in Ukraine is ultimately successful in terms of geopolitical and geo-economic rearrangements in the center of Europe. Moreover, with a currency evaluated in real terms on the world money market, and in synergy with the economies and currencies of the direct partner countries, all more or less in the same situation (…except China!), the whole Russian-centric group will be able to do without the bank-centric monetary artifice.

It is thus, in addition to the immediate geopolitical stake of the geostrategic disengagement of Russia, the “progressive” planetary stake, everything being relative, and in fact, especially anti-banco-centralist, of this war. A stake that the current left, even pseudo “Marxist” and “Marxist-Leninist”, engrossed in its retrograde visions of the world, is completely incapable of understanding!

Luniterre

Apparently, I am a ‘supposed Marxist’ unlike Comrade Viriato. And anybody who knows my books and posts will know that I do recognise secular structural contradictions in capitalism.

Bonjour,

Le texte original en français est ici:

http://mai68.org/spip2/spip.php?article11209

Il y a donc quelques altérations dues à la traduction machine automatique.

Certaines semblent porter sur le fond du texte.

Il me semble avoir vu que vous lisiez également le français.

D’avance, merci de votre relecture éventuelle.

Luniterre

How to end the Ukraine war?

Russia’s publicly declared war aims are for the complete annihilation of the Ukrainian state. Putin has repeatedly denied Ukraine’s right to exist. As long as Russia sticks to this goal, the Ukrainians will fight for their right to exist and for their self-determination.

https://marx-forum.de/Forum/index.php?thread/1073-how-to-end-the-ukraine-war/