The 2021 conference of the International Initiative for the Promotion of Political Economy (IIPPE) took place a couple of weeks ago, but only now I have had time to review the many papers presented on a range of subjects relating to political economy. IIPPE has become the main channel for Marxist and heterodox’ economists to present their theories and studies in presentations. Historical Materialism conferences also do this, but HM events cover a much wider range of issues for Marxists. The Union for Radical Political Economy sessions at the annual mainstream American Economics Association conference do concentrate on Marxist and heterodox economics contributions, but IIPPE involves many more radical economists from around the world.

That was especially the case this year because the conference was virtual on zoom and not physical (maybe next year?). But there were still many papers on a range of themes guided by various IIPPE working groups. Themes included monetary theory, imperialism, China, social reproduction, financialisation, work, planning under socialism etc. It is obviously not possible to cover all the sessions or themes; so in this post I shall just refer to ones that I attended or participated in.

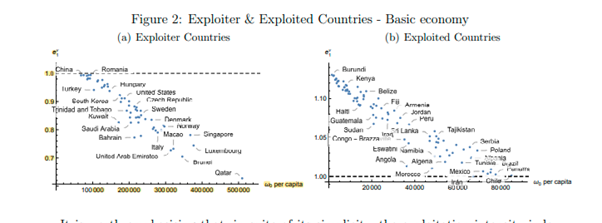

The first theme for me was the nature of modern imperialism with sessions that were organised by the World Economy working group. I presented a paper, entitled The economics of modern imperialism, jointly authored by Guglielmo Carchedi and myself. In the presentation we argue, with evidence, that imperialist countries can be defined economically as those that systematically gain net profit, interest and rents (surplus value) from the rest of the world through trade and investment. These countries are small in number and population (just 13 or so qualify under our definition).

We showed in our presentation that this imperialist bloc (IC in graph below) gets something like 1.5% of GDP each year from ‘unequal exchange’ in trade with the dominated countries (DC in graph) and another 1.5% of GDP from interest, repatriation of profits and rents from its capital investments abroad. As these economies are currently growing at no more than 2-3% a year, this transfer is a sizeable support to capital in imperialist economies.

The imperialist countries are the same ‘usual suspects’ that Lenin identified in his famous work, Imperialism, some 100 years ago. None of the so-called large ‘emerging economies’ are making net gains in trade or investments – indeed they are net losers to the imperialist bloc – and that includes China. Indeed, the imperialist bloc extracts more surplus value out of China than out of many other peripheral economies. The reason is that China is a huge trading nation; and it is also technologically backward compared to the imperialist bloc. So given international market prices, it loses some of the surplus value created by its workers through trade to the more advanced economies. This is the classical Marxist explanation of ‘unequal exchange’ (UE).

But in this session, this explanation of imperialist gains was disputed. John Smith has produced some compelling and devastating accounts of the exploitation of the Global South by the imperialist bloc. In his view, imperialist exploitation is not due to ‘unequal exchange’ in markets between technologically advanced economies (imperialism) and those less advanced (the periphery), but due to ‘super-exploitation’. Workers in the Global South have had their wages driven below even the basic levels for reproduction and this enables imperialist companies to extract huge levels of surplus value through the ‘value chain’ of trade and intra-company mark-ups globally. Smith argued in this session that trying to measure surplus value transfers from trade using official statistics like the GDP of each country was ‘vulgar economics’ which Marx would have rejected because GDP is a distorted measure that leaves out a major part of exploitation of the Global South.

Our view is that, even if GDP does not capture all the exploitation of the Global South, our unequal exchange measure still shows a huge transfer of value from the peripheral dependent economies to the imperialist core. Moreover, our data and measure do not deny that much of this surplus value extraction comes from higher exploitation and lower wages in the Global South. But we say that this is a reaction of Southern capitalists to their inability to compete with the technologically superior North. And remember it is mostly the Southern capitalists that are doing the ‘super exploiting’ not the Northern capitalists. The latter get a share through trade of any extra surplus value from higher rates of exploitation in the South.

Indeed, we show in our paper, the relative contributions to the transfer of surplus value from superior technology (higher organic composition of capital) and from exploitation (rate of surplus value) in our measures. The contribution of superior technology is still the main source of unequal exchange, but the share from different rates of surplus value has risen to nearly half.

Andy Higginbottom in his presentation also rejected the classical Marxist unequal exchange theory of imperialism presented in the Carchedi-Roberts paper, but on different grounds. He reckoned that the equalisation of profit rates through the transfers of individual surplus values into prices of production was inadequately done in our method (which followed Marx). So our method could not be correct or even useful to start with.

In sum, our evidence shows that imperialism is an inherent feature of modern capitalism. Capitalism’s international system mirrors its national system (a system of exploitation): exploitation of less developed economies by the more developed ones. The imperialist countries of the 20th century are unchanged. There are no new imperialist economies. China is not imperialist on our measures. The transfer of surplus value by UE in international trade is mainly due to the technological superiority of companies in the imperialist core but also due to a higher rate of exploitation in the ‘global south’. The transfer of surplus value from the dominated bloc to the imperialist core is rising in dollar terms and as a share of GDP.

In our presentation, we reviewed other methods of measuring ‘unequal exchange’ instead of our ‘prices of production’ method – and there are quite a few. At the conference, there was another session in which Andrea Ricci updated his invaluable work on measuring the transfer of surplus value between the periphery and the imperialist bloc using world input-output tables for the trading sectors and measured in PPP dollars. Roberto Veneziani and colleagues also presented a mainstream general equilibrium model to develop an ‘index of exploitation’ that shows the net transfer of value in trade for countries. Both these studies supported the results of our more ‘temporal’ method.

In Ricci’s study there is a 4% annual net transfer of surplus value in GDP per capita to North America; nearly 15% per capita for Western Europe and near 6% for Japan and East Asia. On the other side, there is net loss of annual per capita GDP for Russia of 17%; China 10%, Latin America 5-10% and 23% for India!

In the Veneziani et al study, “all of the OECD countries are in the core, with exploitation intensity index well below 1 (ie less exploited than exploiting); while nearly all of the African countries are exploited, including the twenty most exploited.” The study puts China on the cusp between exploited and exploited.

On all these measures of imperialist exploitation, China does not fit the bill, as least economically. And that is the conclusion also reached in another session that launched a new book on imperialism by Australian Marxist economist, Sam King. Sam King’s compelling book proposes that Lenin’s thesis was correct in its fundamentals namely, that capitalism had developed into what Lenin called ‘monopoly finance capital’. The world has become polarised into rich and poor countries with no prospect of any of the major poor societies ever making it into the rich league anymore. A hundred years later no country that was poor in 1916 has joined the exclusive imperialist club (save for the exception of Korea and Taiwan, which specifically benefited from the ‘cold war blessings of US imperialism’).

The great hope of the 1990s, as promoted by mainstream development economics that Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) would soon join the rich league by the twenty-first century, has proven to be a mirage. These countries remain also-rans and are still subordinated and exploited by the imperialist core. There are no middle-rank economies, halfway between, which could be considered as ‘sub-imperialist’ as some Marxist economists argue. King shows that imperialism is alive and not so well for the world’s people. And the gap between the imperialist economies and the rest is not narrowing – on the contrary. And that includes China, which will not join the imperialist club.

Talking of China, there were several sessions on China organised by the IIPPE China working group. The sessions were recorded and are available to view on the IIPPE China You tube channel. The session covered China’s state system; its foreign investment policies; the role and form of planning in China and how China dealt with the COVID pandemic.

There was also a session on Is China capitalist?, in which I submitted a presentation entitled, When did China become capitalist? The title is a bit tongue in cheek, because I argued that since the 1949 revolution that threw out the comprador landlords and capitalists (who fled to Formosa-Taiwan), China has no longer been capitalist. The capitalist mode of production does not dominate in the Chinese economy even after the Deng market reforms in 1978. In my opinion, China is a ‘transitional economy’ like the Soviet Union was, or North Korea and Cuba are now.

In my presentation, I define what a transitional economy is, as Marx and Engels saw it. China does not meet all the criteria: in particular, there is no workers democracy, no equalisation or restrictions on incomes; and the large capitalist sector is not steadily diminishing. But on the other hand, capitalists do not control the state machine, the Communist party officials do; the law of value (profit) and markets do not dominate investment, the large state sector does; and that sector (and the capitalist sector) are under an obligation to meet national planning targets (at the expense of profitability, if necessary).

If China were just another capitalist economy, how do we explain its phenomenal success in economic growth, taking 850m Chinese off the poverty line?; and avoiding any economic slumps that the major capitalist economies have suffered on a regular basis? If it has achieved this with a population of 1.4bn and yet it is capitalist, then it suggests that there can be a new stage in capitalist expansion based on some state-form of capitalism that is way more successful than previous capitalisms and certainly more than its peers in India, Brazil, Russia, Indonesia or South Africa. China would then be a refutation of Marxist crisis theory and a justification for capitalism. Fortunately, we can put China’s success down to its dominant state sector for investment and planning, not to capitalist production for profit and the market.

For me, China is in a ‘trapped transition’. It is not capitalist (yet) but it is not moving towards socialism, where the mode of production is through collective ownership of the means of production for social need with direct consumption without markets, exchange or money. China is trapped because it is still backward technologically and is surrounded by increasingly hostile imperialist economies; but it is also trapped because democratic workers organisations do not exist and the CP bureaucrats decide everything, often with disastrous results.

Of course, this view of China is a minority one. Western ‘China experts’ are in one voice that China is capitalist and a nasty form of capitalism to boot, not like the ‘liberal democratic’ capitalisms of the G7. Also, the majority of Marxists agree that China is capitalist and even imperialist. At the session, Walter Daum argued that, even if the economic evidence suggests that China is not imperialist, politically China is imperialist, with its aggressive policies towards neighbouring states, its exploitative trade and credit relations with poor countries and its suppression of ethnic minorities like the Uyghars in Xinjiang province. Other presenters, like Dic Lo and China’s Cheng Enfu, did not agree with Daum, with Cheng characterising China as “socialist with elements of state capitalism”, an odd formulation that sounds confusing.

Finally, I must mention a few other presentations. First, on the vexed question of financialisation. The supporters of ‘financialisation’ argue that capitalism has changed over the last 50 years from a production-oriented economy into one dominated by the finance sector and it is the vissitudes of this unstable sector that cause crises, not the problems of profitability in the productive sectors, as Marx argued. This theory has dominated the thinking of post-Keynesian and Marxist economists in the last few decades. But there is plenty of growing evidence that the theory is not only wrong theoretically but also empirically.

And at IIPPE, Turan Subasat and Stavros Mavroudeas presented yet more empirical evidence to question ‘financialisation’ in their paper entitled: The financialization hypothesis: a theoretical and empirical critique. Subasat and Mavroudeas find that the claim that most of the largest multinational companies are ‘financial’ is wrong. Indeed, the share of finance in the US and the UK has not increased over the last 50 years; and over the last 30 years, the financial sector share in GDP declined by 51.2% and the financial sector share in services declined 65.9% in the countries studied. And there is no evidence that the expansion in the financial sector is a significant predictor of the decline in the manufacturing industry, which has been caused by other factors (globalisation and technical change).

And there were some papers that continued to confirm Marx’s monetary theory, namely that interest rates are not determined by some ‘natural rate of interest’ from the supply and demand of savings (as the Austrians argue) or by liquidity preference ie hoarding of money (as the Keynesians claim), but are limited and driven by movements in the profitability of capital and thus the demand for investment funds. Nikos Stravelakis offered a paper, that showed corporate net profits are positively related to bank deposits and net to gross profits are positively related to the loan deposit ratio and that 60% of the variations in the interest rates can be explained by changes in the rate of profit. And Karl Beitel showed the close connection between the long-term movement of profitability in the major economies in the last 100 years (falling) and the rate of interest on long-term bonds (falling). This suggests that there is a maximum level of interest rates, as Marx argued, determined by the rate of profit on productive capital, because interest comes only from surplus value.

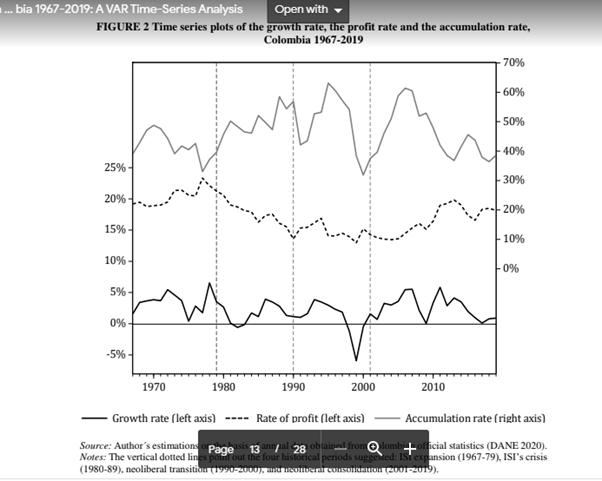

Finally, something that was not at IIPPE but adds yet more support for Marx’s law of the tendency of the profit rate to fall. In the book, World in Crisis, co-edited by Carchedi and me, lots of Marxist economists presented empirical evidence of the falling rate of profit on capital from many different countries. Now we can add yet another. In a new paper, Economic Growth and the Rate of Profit in Colombia 1967-2019, Alberto Carlos Duque from Colombia shows the same story as we have found elsewhere. The paper finds that the movement in the rate of profit is “in concordance with Marxian theory predictions, and affects positively the growth rate. And the GDP growth rate is affected by the profit rate and the accumulation rate is in an inverse relationship between these last variables.”

So the results “are consistent with and provide empirical support for the Marxian macroeconomic models reviewed in this paper. In those models, the growth rate is a process driven by the behaviour of the rate of accumulation and rate of profit. Our econometrical analyses provide empirical support for the Marxian claim about the fundamental role of the rate of profit, and its constituent elements, in the accumulation of capital and, consequently, in the economic growth.”

Links to Ricci and your presentation on China take you to your presentation on imperialism.

Ill correct

DONE!

Nope! Ricci link still loads your presentation!

YIKES, I’ll try again.

I think it is correctly linked now… fingers crossed.

Link to Smith’s article/book is broken.

What is IC and DC in IC-GDP and DC- GDP?

Ill fix that and IC = equals Imperialist countries and DC = dominated countries

DONE! thanks again for spotting these faults

Thanks a lot Michael for the nice summary.

I would have a question, and a comment.

The question(s):

How do you compute the OCC of large monopolies in the imperialist countries that have transferred most of their manufacturing production abroad? Do you count assets like patents etc as constant capital? If yes, how does this kind of constant capital transfers value to the final commodities? It is a bit hard for me to understand how Microsoft, or Apple have a high OCC to be honest.

In relation to this: what happens with “international prices of production” if 1/3 of international trade is internal to big monopolies’ international value chains?

The comment(s):

First of all, I see a progressive convergence between your arguments and those of Smith and Higginbottom on imperialism. You even admit that a different rate of surplus value is becoming more and more important for international value transfers. I think there is a lot of space for more mutual convergence as both views have their strengths.

Second, what I find problematic with your view is that it relies on the rate of profit equalization in the international market and assumes “free competition”, and in that context, attributes technological superprofits to higher OCC instead of technological monopoly rents (see Mandel, but also Thomas Rotta, Jakob Rigi etc).

Again, I find it hard to understand what stands in the way of China, its huge state sector and its huge pile of trade surplus, to invest in the best modern technologies and catch up fast, had those been really freely available as the “free competition” principle assumes. The same goes for other big -but dominated/dependent- countries as well.

I think you are missing that the study of current -later or latest- stage of capitalism assumes that capitalism has a history, that the systemic laws of capitalism (law of value) lead to systematic laws of history of the capitalistic mode of production -> falling of the rate of profit, relative exploitation increase, speeding up of capital turnover, increase of OCC etc etc.

Moreover, there seems to be a trend towards increasing direct (i.e., NOT mediated by commodity exchange) socialization of production (concentration and centralization of capital (Marx, Lenin), conscious, scientific design of production within monopolized industries along international value chains etc, the role of the state in (re)production, especially of the labor power commodity (education, health, basic research)).

In the end of the day, the international market is segregated:

a. by militarized frontiers that do not allow labor power to move freely,

b. patents and other IP, that do not allow capital to move freely…,

c. states in a hierarchy of power that have different potential to reproduce expensive (highly qualified) labour power, exercise military power to secure natural and technological monopolies etc…

This is not how capitalism in the age of Marx or even Lenin was.

Why not allow for history to change substantially the nature of the capitalistic mode of production, if we are really to explain the current reality of capitalism?

Yes, commodity production is the dominant form, but the law of value is skewed by a “law of power” as the above points (a, b, c) demonstrate.

In terms of this, please see the conclusion of Smith’s paper that you link above, where he is suggesting a history of capitalism that looks schematically like:

primitive accumulation -> absolute surplus value (formal subsumption) -> relative surplus value (real subsumption) -> super-exploitation (I would add here formal subsumption of scientific and other creative labour leading to technological monopoly rents, see also Rotta for this).

Now, you have kind of admitted that the capitalists of dominated countries, not being able to compete with the imperialists, have to increase the exploitation of “their” workers.

Well done! You discovered the law of monopoly – superexploitation, which is a dominant tendency in today’s world, in the same way that free competition leads to production relative surplus value!

I have to say that Smith and Higginbottom could also reflect a bit more on your argument about technological superiority in one country against the other.

I don’t agree that the difference in the OCC is the main point, nor that a higher OCC is just an indication of a higher national “mean productivity of labour” (this is a concept not well defined since national products differ a lot in their synthesis across nations, whereas productivity is a property of concrete, not abstract, labour).

However, I do believe that technological superiority reflects a different historical and moral element of the value of labour power, an element that depends both on the long-term results of the class struggle (and therefore can be attributed to differences in exploitation), as well as, and probably predominantly, to a different level of development of the means of production and the capitalistic mode of production, leading to a more expensive -on average- “subject of labour” (more educated, consumer of cultural products etc) in more developed countries. This “more expensive” labour power also performs a concrete labour of higher complexity that produces a more complex product. However, this happens through monopoly technological rents.

Therefore, not all wages differentials, can be attributed to a different exploitation rate. A large part of it corresponds to an inequality of national labour values (i.e., not prices; see also Ricci for this).

Finally, I would like to add that your definition of economic imperialism also works the other way around:

the imperialistic superprofits, this ~2% of imperialistic countries GDP you have computed, is also invested to reproduce a country as imperialistic, in which case the effect becomes also the cause. This is dialectics, this is how not only the law of value, but also the “law of power” asserts and reproduces its self in the international market!

The link to Nikos Stravelakis’s paper isn’t working, there’s something wrong with the file.

Ok will fix

I think I have sorted it.

Thanks it works now.

Can we see the list of papers presented somewhere?

Click to access 2021_IIPPE_ANNUAL_CONFERENCE_PROGRAMME.pdf

“Other presenters, like Dic Lo and China’s Cheng Enfu, did not agree with Daum, with Cheng characterising China as “socialist with elements of state capitalism”, an odd formulation that sounds confusing.”

Why is that confusing?

Capitalism itself existed in a mixed system with feudalism for centuries before it could exist in a “pure” form. So, unless you want to erase 300 years of history of capitalism, I don’t think you could argue it was born ready, from the minds of a group of liberal thinkers.

This sounds even more ironic because the author of this blog comes from a country that still has a royal family. I don’t think there’s any economic theory of capitalism that explains the existence of parliamentary monarchy.

Thank you!! It drives me crazy how this is almost never bought up in discussions around China, or about socialist economies more generally. It’s just so bizarre to me that the most common frame of reference for making sense of the transition from capitalism to socialism isn’t the historical transition from feualism to capitalism.

I find it so strange that people (not talking about Michael Roberts, just people in general) seem to just expect socialism to emerge fully formed and perfectly functioning from the debris of capitalism, like Minerva springing from Jupiter’s head, when that’s never been the case for any previously existing mode of production. Isn’t it much more realistic to expect said transition to take hundreds of years, as it has always done in the past?

Anyway, great article Michael Roberts- sounds like a very interesting conference! And I actually think your characterisation of China is very apt. Incidentally, I was in a webinar with Isabella Weber (author of How China Escaped Shock Therapy) and she characterised China in almost the exact same way.

In China, we are told, “capitalists do not control the state machine, the Communist party officials do.” Private capitalists do not control the state machine. Instead, Communist officials are capitalists. They pile up fabulous holdings of enterprises. They are able to treat state firms much as their own. The scramble for profit is universal. For an illuminating, even if anecdotal, account loaded with evidence of this, read Red Roulette by Desmond Shum.

The characterization of China as “stuck transitional” state may sound reasonable, but there are a few problems:

1) China and any other social formation cannot be characterized in a vacuum, independently of a now highly integrated *capitalist* states world-system that is still one divided between nations as also described by Lenin over 100 years ago.

2) Therefore dominance/non-dominance of a mode of production is not a sufficient criterion for the correct characterization of a single social formation integral to the world-system in 1).

3) Further, there is no Marxist requirement that there be a dominant mode of production *at all times* in a given social formation. This implies that there can be more than one mode of production within a given social formation.

Historical analogy example: 16th C England, where the feudal-seignorial mode of production (“serfdom”) had already dissolved, could also be characterized as in an “intermediate” state (but not “stuck transitional”, as the English Tudor ruling classes weren’t heading anywhere), with production now on a household commodity producer basis in both agriculture and manufacture (employing itinerant peasant wage labor in addition to the household), without this mode of production being *dominant* (let alone “capitalist”, it was not), as “dominance” of a mode of production implies political and ideological components as well. But no mode of production was dominant in 16th C England.

However a *feudal* states system still dominated the (much smaller then) European world system, and therefore England is correctly characterized as a feudal state until the English Revolution. The *state* (not the social formation nor the mode(s) of production) was “intermediate” during the Restoration, and Parliamentary supremacy – the institutional instrument of the landlord gentry and their yeoman and merchant allies – was secured after 1688. At that point the “transition” to a bourgeois state – “deformed” by the presence of a hereditary landlord gentry that, however commerce friendly, was a relic of feudalism – was complete.

Hence China is an “intermediate” capitalist *state* with no dominant mode of production (but with a capitalist mode of production). I would not use “transition”, stuck or otherwise, since the Chinese bureaucratic dictatorship has no intention of transitioning to socialism – the subjective factor is crucial here in this determination, as Lenin also said.

Hence the Chinese bureaucracy *is* attempting to forge a new historical path of development within the contemporary capitalist world-system, without overturning that system or allowing the capitalist mode of production to achieve dominance within China. In other words, it is Beijing that must prove classical Marxism, including Lenin, wrong! (That to Alan Freeman!)

As a “neo-classical” Marxist, I therefore predict they will fail. Even the USA could get only so far in the epoch of capitalist decay – a characterization also from Lenin, and supposedly refuted by the post war “golden age”, until that turned out to be fools gold.

Interesting review Michael, thanks. I have a question on UE and I would appreciate it if you could help me with an answer or point to something you or someone else has written on the topic. You said:

“The reason is that China is a huge trading nation; and it is also technologically backward compared to the imperialist bloc. So given international market prices, it loses some of the surplus value created by its workers through trade to the more advanced economies. This is the classical Marxist explanation of ‘unequal exchange’ (UE).”

We know that for Marx, capitalist exploitation happens in the production process and that explains capitalist profit. So how come and “imperialist exploitation” is the result of exchange relations between nations (“unequal exchange”) and not relations of production enforced by stronger (imperialist) states on weaker ones? I am not denying that unequal exchange happens between countries (and part of my question is “how OCC differentials between countries contribute to that?”), just as unequal exchange probably also dominates everyday market exchange within a country. But we wouldn’t call the latter “exploitation” in the Marxist sense.

“So how come and “imperialist exploitation” is the result of exchange relations between nations (“unequal exchange”) and not relations of production enforced by stronger (imperialist) states on weaker ones?”

Indeed this was until now the main theoretical problem of the ‘dependancy’ school of thought.

Not being able to explain capitalistic production in terms of unequal exchange and monopolistic competition, and vice-versa.

This is where Andy Higginbottom and John Smith come in to argue that the essence of the imperialist historical stage of capitalism is the superexploitation of southern labour by northern capital (“northern” and “southern” stand here for “imperialist” and “dependent/dominated” nations).

The point is that along international value chains capitalistic production (of surplus value and, therefore, profit) is organized -more and more- in a qualitatively different way than before.

Before, (relatively) independent capitalists would compete to lower costs by improving technology, which as a cumulative result, would lead to the production of extra, additional surplus value, as relative surplus value.

Today, capitalists that produce commodities of different complexity (different demand elasticity, different degree of monopolization etc), or that have very different roles in the production of final, very complex commodities, and exchange between them “internally”, at “arms length”, etc, organize production on the basis of different power relationships, which, as Michael suggested*, as well as others (see Starosta**), breaks them into roughly two groups:

– those who can compete technologically and capture either higher profits via higher productivity (the technology being though IP protected), or who can capture monopoly technological rents (see Mandel’s Late Capitalism),

– those who, due to fierce competition within their group, have to increase the exploitation rate, by applying more oppressive exploitative practices in the capital – labour relationship.

Between these two groups we also find large differences along the axis of productive – non-productive labour as well…

So, the whole circuit of capital reproduction is altered:

– production of surplus value -> superexploitation on the one hand, kind of labour aristocracy on the other,

– circulation of surplus value -> systematically unequal commodity exchange (including the commodity labour power as superexploitation suggests), as for instance in “internal international trade”

– distribution of surplus value -> technological (in addition to “classical” natural) monopoly rents, profit rate not really equalized.

more and more in the place of

– production of surplus value by free labour with a unified rate of exploitation

– circulation of surplus value in terms of equivalent commodity exchange (in the long run, after “frictions” have dissipated),

– distribution of surplus value in terms of “free competition”, i.e., under free circulation of labour, capital, and technology, with the only exception of natural or accidental – and therefore very transient- monopolies.

My suggestion is that power relationships more and more “skew” the operation of the law of value, not only in the international market, but also within each country.

“Power” instead of “exchange value” regulates systems in which production is socialized directly, i.e., not mediated by exchange relationships, and in general, at large scale. This is the case particularly for scientific, or artistic, highly creative labour, which doesn’t produce commodities itself, but it is a precondition for the production of novel, innovative use-values (that take one way or another the commodity form in capitalism).

This happens for instance regarding the role of the state in the reproduction of labour power (health, education and basic scientific research systems), in the imposition of state monopoly regulation (tax systems, public finance policies, IP protection, etc), etc.

Moreover “power” is under relationships of “exploitation by dispossession”, as for instance in the case of natural monopolies in dominated countries being exploited by imperialistic monopolies, thanks to …NATO practices…

Regarding the international division of labour, or in your words, “relations of production enforced by stronger (imperialist) states on weaker ones”, see also the work of Wise et al:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321318964_The_political_economy_of_global_labour_arbitrage

https://monthlyreview.org/2021/03/01/capital-science-technology/

*Michael writes:

“Moreover, our data and measure do not deny that much of this surplus value extraction comes from higher exploitation and lower wages in the Global South. But we say that this is a reaction of Southern capitalists to their inability to compete with the technologically superior North. And remember it is mostly the Southern capitalists that are doing the ‘super exploiting’ not the Northern capitalists. The latter get a share through trade of any extra surplus value from higher rates of exploitation in the South.”

**Starosta claims something like that there are branches of capitalistic production in which large, technologically advanced (monopoly I would say…) capital doesn’t find it profitable to enter. Such branches have a rate of profit lower than the general rate of profit, but still higher than the interest rate. So, they survive and systematically reproduce themselves as such… Starosta does not accept the notion of “monopoly” capital, by equating the regulating capital that drives the profit equalization to what I call monopoly capital, and by excluding the technologically less advanced capital from the equalization of the profit rate… DIfferent words for the same reality, but… words matter in this case…

https://cicpint.org/en/starosta-g-2010a-global-commodity-chains-marxian-law-value-antipode-422-433-465-2/

Thanks for the detailed response! I got to say, I am “inching” more towards Smith’s approach even though I find the term “super-exploitation” problematic because the emphasis on “super”, I think, is redundant. Marx did not talk about super exploitation of victorian workers. He talked about absolute and relative surplus value and maybe absolute surplus value is the best descriptor for what Smith is trying to communicate. That is, *capitalist profit* whether it is in the home country or abroad (through FDI), it has to come from exploitation. Now, maybe this is not the case. That is why I posted the question. Because there is certainly the case of “unequal exchange” between nations, but I don’t exactly understand how this happens? Is it like, through currency manipulation? If it is through OCC, then one would expect that countries with lower OCC would eventually be pushed out from international markets (for a particular industry). If this is not the case, then why maintain a bad/losing position trading in international markets? How did Huawei manage to “break” the cellphone monopoly market, offering products at a third of the price for same quality? It certainly didn’t have higher OCC. Apple was simply extracting rents. I just think the idea of higher OCC implying automatically an exploitative relation between nations somewhat strange.

You are welcome!

Following Michael’s link to John Smith’s Monthly Review article, most of your points are answered:

“Not only did Marx leave to one side the reduction of wages below their value, he made a further

abstraction that, while necessary for his “general analysis of capital,” must also be relaxed if we

are to analyze capitalism’s current stage of development: “The distinction between rates of surplus

value in different countries and hence between different national levels of exploitation of labour

are completely outside the scope of our present investigation.”31 Yet it is precisely this that must

form the starting-point for a theory of contemporary imperialism. Wage-arbitrage-driven

globalization of production does not correspond to absolute surplus value. Long hours are endemic

in low-wage countries, but the length of the working day is not the outsourcing firms’ primary

attraction. Nor does it correspond to relative surplus value. Necessary labor is not, in the main,

being reduced thorough the application of new technology. Indeed, outsourcing is often seen as

alternative to investment in new technology. It does, however, point to super-exploitation. As

Higginbottom argues, “Super-exploitation is…the hidden common essence defining

imperialism…. This is not because the southern working class produces less value, but because it

is more oppressed and more exploited.”32”

Indeed, Marx observed super-exploitation but though that doesn’t have a central space, as a substantial concept, for the general theory of the capitalistic mode of production (CMD).

Apparently, though, today’s reality of CMD, requires such a central concept as a third way of increasing surplus value, one that doesn’t assume, though, the full reproduction of labour power as commodity, and therefore, the latter can be priced systematically below its value.

Clearly this is an alternative to increasing productivity (relative) or increasing labour time (absolute) surplus value.

By the way, one way that this happens is by manipulating prices ini exchanges between monopolies and industries that produce at arms’ length, or in what is called “internal” trade, i.e., trade between mother companies and their …siblings!

This is how the extra surplus value is transferred, but you are right, it is not how it is produced, which at large this is via super-exploitation.

I also agree that monopoly technological rents have become more important than OCC nowadays…

This is like ground hog day. Two years ago, during your last report it also focused on the nature of imperialism. At the time I criticised your view on the transfer of surplus value to the dominant economies. You even forced me to write two articles in response. Firstly you understated the flow using your own calculations. I provided a method of using the variation between the IPI (Import Price Index) in the USA and the PPI (Producer Price Index) which yielded a flow of 4% similar to Ricci’s study which you quote. I also analysed the global car industry to show that super-exploitation, which you reject, does occur between workers of similar productivity, using similar compositions of capital but who suffer much lower real wages. If you don’t believe me ask the German executives who run Volkswagen and Mercedes Benz in China. In response to one of the comments in this post, the BEA (Bureau of Economic Analysis in the USA) redefined manufacturers who discontinued their US operations and outsourced them to China, as no longer manufacturers but wholesalers. They know a thing or two. So the profits of these wholesalers now originated in China. https://theplanningmotivedotcom.files.wordpress.com/2019/11/super-exploitation-pdf.pdf

My main concern is this imperialist navel gazing through defining imperialism by use of category rather than empirical data. In the two years since the last conference China has perfected its first modern fighter jet engine, next year it will be producing 14nm chips, the backbone of the industry, using recently developed Chinese equipment from A to Z. KPMG warned Trump that his embargoes would force the Chinese to develop their own technical architecture which they are rapidly doing. Why do you think the US is scrambling to assemble a military coalition of the Anglo-Saxons to confront China, because it knows the writing is on the wall. The US, when it loses its technical supremacy loses everything. That is what turns economic competition into military confrontation. This approach is so much more exciting than the sterile debate whether China is a sub-imperialist economy, which it is, or a fully fledged one.

Finally, what is driving all this, including constipated supply chains? It is the exhaustion of the phase of globalisation beginning in 2014 in the dominant countries and ending in 2016 in the dominated countries. It was this collapsed profitability that intensified competition, which broke up arrangements, that led to more intense cost cutting particularly in the realm of supply chains and just in time. And so here we are, with Stock Markets trembling at the prospect of a broken world economy. Surely that is what the academics in this conference should have been pre-occupied with.

On China, Michael made a valiant effort to summarize my talk in one sentence. At greater length, my notes for it are here: https://www.academia.edu/54327649/Is_China_Imperialist_2021_. They are part of a longer project, “Capitalism with Imperialist Characteristics – A Marxist Theoretical Inquiry into the Class Nature of China.”

This comment is in response to Michael Roberts’ remarks on the controversy among marxists regarding “financialization.

Most marxist quote Lenin in characterizing imperialism as finance monopoly capitalism. Then they forget it, maybe because the term is not exclusively economic, but a product of historical materialist thinking.

If we understand “financialization”, not as referring literally to the activity of banks, but as the “point of view” of US bankers like Blackstone’s Swarzmann, who, along with his protégée, BlackRock’s Fink, used loaned bank capital to establish a new kind of private equity fund that is able (under conditions of falling rates of profit) to accumulated enough dormant capital to eventually own major shares in the banks and the corporations in which it invested. Davos has sanctified Fink. Such funds (the largest centered in the US) have multiplied, because they allow for further concentration of capital invested, not in banks, but in means of production in way that allows for accumulation (in individuals’ accounts) via profit, interest, and rent—often hedged one against the other.

I try to keep my comments brief but I have to complete my above comment in which I have characterized Lenin’s definition of imperialist as reflecting a historical materialist analysis, which is to say, one which synthesizes both the economic and political characteristic of imperialism.

In Robert’s previous post on the German economy I pointed out that the neoliberal period of the imperial system had two political objectives: the colonization of labor within the core imperial countries (like German and the hergemon of the sytem, the US) and the recolonization of the ex-colonies, and that the single most powerful weapon in achieving this objective is the IT industry. The activity of Eric Schmidt, the major individual stock-holder in Alphabet/Google, and as chairman of the US defense department’s Defense Innvatuio Board, is the personification Silicon Valley’s connection to the US’ milititary industrial/surveillance complex and its colonizing labor/recolonization process.So are all the mulitibillionair stars of this very profitable industry: Amazon’s Bezos, Facebook’s Zuckerberg, Google’s Gates, etc. They also personify the “financializtion” of the neoliberal stage of imperialism: it’s celebrity capitalist face–Schmidt is the major individual sharehold of Alphabet/Googel, but capital-organizing funds–Vanguard, BlackRock, Fidelity, Rowe Price, State Street, JP Morgan-hold the majority of shares.

This is full of typos: Germany for German, hegemon for hergemon, innovation for innvatuio, Microsoft’s Gates for Google’s Gates.

Walter, I have read your paper. It poses important questions. When comparing China to the the dominant economies, EU, Britain, North America and Japan, I always urge a word of caution which I first expressed to Michael a few years back when he was contemplating a book on China. China is a split economy. The gap between its metropolitan and rural areas is huge, rural income being only 1/4 of metropolitan areas. If we strip out the rural areas and just take the metropolitan areas, a different picture emerges. In 2016 “Brookings” examined the top 300 metropolitan areas that comprise the global economy and found that while they only housed 20% of the global population they produced 50% of global GDP. And they pointed out that China was beginning to dominate this metropolitan landscape. If that was true by 2016 it is even more the case today because China’s economy has grown by 30% relative to the USA. I would argue that China’s metropolitan areas in terms of productivity and GDP are indistinguishable from any other except in this respect, it is more modern and its infrastructure is more highly developed. https://www.brookings.edu/on-the-record/the-global-metropolitan-revolution/ This year Brookings has brought out their latest evaluation of China in book form whom they now designate a major global power and I intend to review it shortly on my website.

Hi, I was wondering if people in your conference group might be interested in my 30+ year academic obsession with the quantification of ecological & social justice & sustainability via the principles of ecological systems modelling & thermodynamics, as a basis for non-species-biased, non-property/trade/currency-based, and non-hierarchical (aka anarchic) justice economics & politics …?

In a nutshell, it means that we can achieve justice without law, economics without property trade or currency, and politics without authority or hierarchies of power.

In practical terms it means that the transfer of goods and services is achieved by way of the following:

1 — for anything that is abundant ( supply greater than demand ), so long as our means of harvest, production / processing / manufacture, distribution, storage, maintenance, operation, refuelling, recycling etc., do not themselves turn an abundant resource into a scarce resource, nor cause deleterious ecological or social consequences greater than the capacity of society and ecology to heal, repair, and renew … then all such abundant resources can be distributed to anyone who asks without payment or trade

2 — but we still record the transfer ( in a specialised blockchain architecture I have designed )

3 — for anything that is scarce ( demand greater than supply ), we can still transfer the object for free, but in this case we want to know where to distribute to, and this is determined by an analysis of the information in that blockchain, which tells us which options have the best history of causing the least deleterious consequences, and creating the greatest beneficial consequences, plus other factors such as the current intended usage for each transfer, and associated potential to reduce further harm and increase further benefits in both ecological and social terms, quantified in real scientific units of measurement, and taken from a non-species-biased perspective

4 — since the systems are not based on law or authority, anyone producing any goods or services is also free to ignore this advice on the distribution of their objects, but if they do so, they must take responsibility for the consequences of that choice … thus the system respects personal sovereignty and autonomy while also accounting for personal responsibility

5 — since there’s no requirement to work at all, or contribute to society in any way, many people might just choose to be a beach bum or whatever takes their fancy, but the more people who do so, the less goods and services are abundant, and since access to scarce resources is partially dependent on your history of beneficial and deleterious consequences of your actions, this creates a feedback loop into motivating people to contribute in some way … and similarly, the more people who contribute, the less things are scarce, which creates a feedback loop into people needing to do less to get what they need … thus the system is always in balance

6 — since converting a scarce resource into an abundant one, without simultaneously causing ecological or social harm greater than the benefits of such abundance, is itself a beneficial action, thus over time more things are made abundant, as responsibility for this beneficial outcome would give a person greater access to those things that remain scarce … similarly, the same being true for maintaining the abundance of a resource, or reducing harm in production or utilisation or recycling etc., are all beneficial outcomes we are motivated to achieve, such that these outcomes result in beneficial ecological and social consequences from a non-species-biased perspective … and you can imagine for yourself all the other things which can be extrapolated from these examples … everything has this constant feedback loop

7 — therefore abundance is always maintained ( where possible and to the best of our ability ), finding new methods which are better than past methods for every element of our actions is always pursued, reducing harmful outcomes is always pursued, sharing information is beneficial, hoarding information is usually deleterious, and so on and so forth on every imaginable issue … and all quantification is always done from a non-species-biased perspective … thus over time, as more data is collected and the system evolves, everything improves, and people are retrained OUT of the mindset of mindless consumption exploitation destruction inefficiency pollution and wastefulness, and into a mindset of concern over consequences, but without requiring people to actually care about or even understand it, because they can always just hire someone ( at no cost ) to handle this for them, but the trend over time is still a retraining of attitude … such that we don’t need to create a popular movement for change and expect people to agree and understand a bunch or complex ideas, all you have to do is get the systems running and demonstrate with some test projects how this can all be used to benefit individuals, and over time people find their own reasons to use it, and the more it gets used, the more it grows and evolves, and the less this new economic paradigm requires interaction with the external economy to fulfil needs it cannot yet fulfil internally

8 — so taking a view outward now … the fledgling system interacts with the existing economic paradigm of capitalism by way of a bi-directionally translating interface and buffer, which is implemented in the form of an ethical investment fund and other organisational structures ( which again I’ve designed ), and which use the information in the blockchain I spoke about earlier, combined with an algorithm dealing with relative / proportional responsibility for productive output, and also combined with a system which prevents capital investors having permanent ownership or control of anything ( thus becoming parasites and sabotaging the objectives and principles in operation ) … thus both project workers and capital investors are seen as investors on an equal / fair / proportional footing, with no one able to use any leverage or bargaining position to get more than their input was really worth, while also building into the profit distribution system — where by profit I’m referring to any money generated by interaction / export to the external world of capitalism which it still exists — a “half-life” of the productive benefits of all inputs ( labour and capital alike, but also including productive inputs from nature’s ecosystems and species which are represented in that blockchain as well ).

I hope that’s an adequate description for you … it’s very hard to do it justice on this tiny phone screen tying with my thumbs on a tiny keyboard into a tiny text box … but if you have any questions, just let me know and I’ll send you an email so we can talk there

Hats off to Michael, for organising this panel, and for his report.

Below I dispute Michael’s careless characterisations of the views I expressed in said IIPPE panel, followed by a question to Michael, and an acknowledgement of where we agree.

But challenging Michael’s careless characterisations is one thing. To stop going around in circles and to move this debate forward it is necessary to get much deeper into the discussion around key concepts such as unequal exchange, dependency, imperialism, exploitation and super-exploitation. I’ve written a response to Michael’s blog post on the IIPPE panel and to his and Carchedi’s paper which is much too long to be posted as a comment. I will publish it in the near future, once I’ve gleaned some comments from co-thinkers.

Michael misrepresents my views as follows:

First, he claims I argue that “imperialist exploitation is not due to ‘unequal exchange’ in markets between technologically advanced economies (imperialism) and those less advanced (the periphery), but due to ‘super-exploitation’,” by which he says I mean “wages driven below even the basic levels for reproduction;” and he claims that, in so doing, I “reject the classical Marxist unequal exchange theory of imperialism.”

Second, he claims that I “argued in this session that trying to measure surplus value transfers from trade using official statistics like the GDP of each country was ‘vulgar economics’ which Marx would have rejected because GDP is a distorted measure that leaves out a major part of exploitation of the Global South.”

Claim #1

In the IIPPE panel that Michael organised, in the book he reviewed, in my paper to the 2019 HM conference which Michael also organised, and elsewhere, I’ve argued, both verbally and in writing, that the higher capital intensivity (reflected in a higher organic composition of capital, or OCC) of ‘technologically advanced economies’ gives rise to value transfers from lower OCC, underdeveloped economies, and that this is a prime factor inducing ‘unequal exchange’. For example, in ‘Imperialism in the 21st Century’ I say that “To the considerable extent that capital-intensive capitals are concentrated in imperialist nations and labor-intensive capitals in low-wage nations, [this] implies a S-N transfer or redistribution of value that… is not captured in GDP data,” pointing out that “This [is] the only basis for unequal exchange accepted by dependency theory’s Euro-Marxist critics.” (p273).

However, I also argue that differences in OCC are not the only, or even the main, cause of ‘unequal exchange’—value transfers to imperialist countries from dominated countries also result from higher rates of exploitation in the export-oriented economies of the latter, that these higher rates of exploitation are the product of many factors, political as well as economic, and that during the neoliberal era they have been the main driver of the vast relocation of labour-intensive production processes to low-wage countries.

So, in contrast to Michael’s simplistic, one-dimensional approach, I do not crudely counterpose differences in OCC to differences in s/v, and still less do I reduce the latter to a simple function of the former.

Claim #2

I’m incredulous. Do Michael and Guglielmo really believe it is possible “to measure surplus value transfers from trade using official statistics like the GDP of each country”? Yes, glimpse. Yes, ‘see the shadow of’. Yes, ‘visible portion of the iceberg’. But measure? Really???

The central point I made in my 15 minutes contribution to this session, repeating arguments developed in works referenced above, was that a health warning must be attached to all data on GDP, productivity, and trade because they are concocted from value-added, namely, the prices a firm receives for all outputs minus the prices paid for all inputs from (GDP being the sum of the value-added of all firms within a given economy). The problem with value-added—the source of what I have called ‘The GDP illusion’—is that it assumes that all of the value captured by a firm was generated by activity taking place in its own hidden abode of production, and that none of it has been captured from other firms elsewhere in the national or global economy. The result is the conflation of value and price and is the hallmark of bourgeois economics a.k.a. vulgar economics. The reductio ad absurdum of this bourgeois category of value-added can be seen in official data which shows that the most productive people on this planet, i.e. those with the highest value-added per capita, are financiers resident in tax havens!

‘Value-added’, I and Andy argued in this IIPPE panel, is nothing else than a crude version of Marx’s prices of production, and I cited an extremely relevant passage in volume 3 of Capital, where Marx argues that vulgar (i.e. bourgeois) economists,

“always speak of the prices of production as the centres around which market prices fluctuate. They can allow themselves this because the price of production is… [a] prima facie irrational form of commodity value, a form that appears in competition and is therefore present in the consciousness of the vulgar capitalist and consequently also in that of the vulgar economist.”

So, Michael garbles this key element in my argument. Marx would indeed have argued that GDP and other value-added statistics conceal more than they reveal. He has never commented on my critique of value-added more of the ‘GDP illusion’ generated by this mystified, bourgeois category,

I’m grateful for Michael’s commendation of my “compelling and devastating accounts of the exploitation of the Global South.” But this is faint praise, since he ignores my attempts to contribute to the theory of the imperialist form of the law of value, or caricatures where ignorance is not an option. And it’s pitiful to see Andy’s lustrous pearls trampled under unappreciative cloven hooves…

What ‘classical Marxist unequal exchange theory of imperialism’???

Michael claims that I (and “for different reasons” Andy Higginbottom, another member of the IIPPE panel), “reject the classical Marxist unequal exchange theory of imperialism.” Ouch!—no, that’s not what I feel about Michael’s put-down, it’s the pain from biting my tongue to avoid saying what I think of it. Maybe Michael is retaliating for being charged with ‘vulgar economics’ on account of his readiness to use the bourgeois category of value-added as a proxy for the Marxist category of value. Fair enough. But if the cap fits…

Back to my question. What ‘classical Marxist unequal exchange theory of imperialism’ is Michael referring to? Is it to Marx, who so brilliantly succeeded in developing a ‘general theory’ of capital, but who never developed a theory of capitalism’s imperialist stage of development—and neither could he have done, because he wrote Capital before capitalism had entered its highest imperialist stage? Or is it to dependency theory, which coined the term ‘unequal exchange’, and which revived inquiry into the Marxist theory of imperialism after decades of neglect, but did so before ‘neoliberalism’, i.e. capitalism’s fully developed imperialist stage (but is now experiencing a major revival), had begun? Or is it to the euro-Marxist opponents of dependency theory, who subverted classical Marxist theory while claiming allegiance to it, dogmatically insisting that the value relations of the contemporary global economy are identical to those in the idealised marketplace analysed by Marx in his quest for a ‘general theory’ of capital, and that none of the simplifying assumptions he made to that end need to be relaxed?

Michael’s answer, it seems to me, is “all of these”; in other words, he eclectically and confusingly attempts to combine all three together. Before we examine the resulting deficiencies in his argument, its hugely positive aspect should be noted. For all its confusions, his and Carchedi’s paper points towards what we need: a genuine synthesis, a Marxism-Leninism for the 21st-century. Their recognition of the scale and importance of imperialist value-extraction from dominated countries and their embrace of the concept of unequal exchange signifies a break with imperialism-denying euro-Marxism, and their paper should be counted as an important contribution to 21st-century dependency theory. Welcome aboard, this ship is ready to sail! But actually you’re still on the gangplank—a dangerous place—and you still have a few steps to make!

Where we agree

I agree with Michael’s statement that “imperialist countries can be defined economically as those that systematically gain net profit, interest and rents (surplus value) from the rest of the world through trade and investment”—this is true, but it is not the whole truth. What this definition says is extremely important, but what it leaves out is also extremely important, such as racism, national oppression, systematic divide and rule, violation of the equality of proletarians, monopoly in all its forms. As I stated in my paper to the ‘economics of imperialism’ panel organised by Michael at the 2019 HM conference,

Imperialism is today manifested in an apartheid-like global system of racism, national oppression, cultural humiliation, militarism and state violence that makes a mockery of the South’s workers’ and farmers’ formal status as free citizens of their nations and of the world, and has converted their countries into reserves of super-exploitable labour-power for transnational corporations and their suppliers to gorge themselves on.

None of this is hidden from view. The nakedly exploitative character of apartheid capitalism in South Africa was just that—naked, unveiled, apparent to all with eyes to see; and so it is with 21st century imperialist capitalism. The systematic violation of equality between proletarians is incontrovertible, and so are the divergent rates of exploitation that necessarily flow from this—how could it be otherwise, given that value relations are social relations?

This is why what we need not so much an ‘economics of imperialism’ but a political economy of imperialism! Just as apartheid capitalism in South Africa cannot be reduced to or fully explained by the difference between the organic composition of capital in goldmines and in the industries in the ‘mother country’ they helped to finance, neither can contemporary imperialism be conceptualised in such a simplistic manner!

Hypertext links to sources cited in my comment got lost in translation, so here they are:

Michael’s review of ‘Imperialism in the Twenty-first Century’: https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2016/03/07/imperialism-and-super-exploitation/

‘The GDP Illusion’ (chapter 9 of Imperialism in the Twenty-first Century): https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348923819_The_GDP_Illusion_Chapter_9_of_Imperialism_in_the_Twenty-First_Century

Exploitation and super-exploitation in the theory of imperialism

https://www.academia.edu/41073671/Exploitation_and_super_exploitation_in_the_theory_of_imperialism_v

You said “…no country that was poor in 1916 has joined the exclusive imperialist club (save for the exception of Korea and Taiwan…)

What about Finland? They were poor in 1917 but are one of the wealthiest now.

Tony Interesting question. It’s true that Finland in the early 1900s was poor on a per capita GDP basis compared to the other Nordic countries, But at the time it was actually richer than Japan or Russia and Korea by some distance. So I am not sure it fits the bill as a country that was dominated by imperialism and then joins the imperialist bloc. Japan was joining the imperialist club just about then with a lower per cap GDP than Finland. https://www.nationmaster.com/country-info/stats/Economy/GDP-per-capita-in-1900