Global stock markets ended 2016 near record highs and have started 2017 in a similar vein. Optimism about global economic growth, employment and incomes has bounced.

The latest data on manufacturing, as measured by the so-called purchasing managers’ index (PMI), the view of companies on their sales, exports, employment and orders, show a rise in December across the board and particularly in Europe and the US. PMIs measure whether manufacturing companies think that their activity is expanding or contracting. Anything above 50 suggests expansion. In Europe, the PMIs suggest that manufacturing is now expanding at a record pace (from a low level), while the global average PMI has now reached levels not seen since 2013.

Gavyn Davies, former chief economist at the infamous investment bank, Goldman Sachs, now blogs in the Financial Times and produces a measure of global economic activity with his Fulcrum Nowcast model. The latest monthly estimates show that economic growth has recovered markedly from the low point reached last March. Then fears of global recession were high. But Davies says now “not only were these fears too pessimistic, they were entirely misplaced. Growth rates have recently been running above long-term trend rates, especially in the advanced economies, which have seen a synchronised surge in activity in the final months of 2016.”

According to Fulcrum, the growth rate in global economic activity is currently running at 4.1 per cent, compared with an estimated trend rate of 3.8 per cent. This represents a vast improvement on the growth rates recorded in 2015 and early 2016, when growth dipped to below 2.5 per cent at times. The latest estimate for the advanced economies shows ‘activity growth’ running at 2.5 per cent, a rate achieved only rarely during the post-crash economic expansion.

JP Morgan investment bank is also more optimistic, if only a little. “Our global economic outlook calls for a 2.8% gain in global GDP in 2017 (4Q/4Q), a few tenths above potential. The year-ago rate bottomed out at 2.5% this year (during 1Q16-3Q16, we think), so the forecast represents a modest though still meaningful improvement over recent performance.” Goldman Sachs takes a similar view in its look ahead to 2017: “We expect global growth to improve modestly, from 2.5% in 2016 to 2.9% in 2017, with looser fiscal policy and still easy monetary policy in key countries.” goldman-sachs-isg-outlook-2017

As I argued in my forecast for 2017, optimism that the world capitalist economy is now getting permanently out of its depressed state is driven by the possibility that the new US President Trump will activate a Keynesian-style fiscal stimulus of corporate tax cuts and infrastructure spending that will ‘pump-prime’ the US and other economies out their weak growth.

At the same time, China, having been close to a financial crash, according to mainstream economics this time last year, has steadied and is also picking up some traction. Indeed, China’s pick-up has confounded mainstream expectations that China’s seven-year credit boom, during which the debt/GDP ratio rose from 150% to 250%, would inevitably end in 2016. Almost all non-Chinese economists anticipated a significant slowdown, which would intensify deflationary pressures worldwide.

But the Chinese economy is a weird beast, not understood by mainstream (and even Marxist economists). President Xi may have endorsed in 2013 “the decisive role of the market,” but that hasn’t diminished the leading role of the state. As Aidan Turner put it recently, “Suppose that a full quarter of Chinese capital investment – currently running at around 44% of GDP – is wasted: that would mean China’s people are unnecessarily sacrificing 11% of GDP in lost consumption: but if the remaining 33% of GDP is well invested, rapid growth could still result. And, alongside obvious waste, China makes many high-return investments – in the excellent urban infrastructure of the first-tier cities, and in the automation equipment of private firms responding to rising real wages.”

Thus, according to Fulcrum, emerging economies are currently growing steadily at close to their 6 per cent trend rate, or 2 percentage points higher than achieved in 2015. They have therefore ceased to be a drag on the global expansion. No wonder stock markets are off to the races.

I won’t repeat myself with the arguments I presented against the view that capitalism has turned the corner and is entering a new boom period. I made these in my last post. But let me now add some caveats to the optimism of the banks, hedge funds and other financial institutions in investing our pension funds and savings in the stock market.

First, the expert financial consultants are notoriously wrong in their forecasts. Since 2000, they have predicted the S&P 500 would gain about 10% a year, grossly overshooting the market’s actual performance. And, on average, the consensus always has predicted annual gains, missing all five down years in that stretch. A study by CXO Advisory Group collected more than 6,500 forecasts from 68 so-called market gurus. More were wrong than right.

Second, in the last analysis, stock market prices depend on the expected earnings (profits) of companies. The ratio of the market valuation or price of the US stock market is now pretty high compared to profits by historic standards. When profits are set against the value of a company’s assets, the so-called return-on-equity for the top five listed companies in each industry is double that of the rest. And indeed, if you exclude the top five companies in each sector of US business, profitability (return on stocks purchased) is near 30 year-lows. In other words, earnings are concentrated in the very big oligopoly firms. Most American corporations are scratching a return.

And third, as I have pointed out before, corporate indebtedness has also been rising. A company’s value is measured by investors by its liabilities (net debt and stock value). Currently, those liabilities are at levels compared to earnings not seen since the dot.com collapse of 2000-1.

Finally, the US stock market relative to GDP is nearly back to the level seen just before the global financial crash in 2007-8. In other words, it is reaching extremes compared to the sales revenues and profitability of companies.

Stock prices are being artificially driven up by corporations using their profits to buy back their own shares or make higher dividend payments. According to research by WPP, a global communications firm, among companies listed on the S&P 500, share buybacks and dividends have exceeded retained earnings (that is, profits withheld by companies and generally earmarked for investment) in five of the six quarters up to June 2016. Moreover, the ratio of payouts and buybacks to earnings has risen from around 60 percent in 2009 to over 130 percent in the first quarter of 2016.

The locus of what is going to happen to the global economy over the next year or two is to be found in the US. This remains the largest and most productive economy in the world, including manufacturing, and of course so-called services and finance. And the ‘recovery’ after the end of the Great Recession in 2009 has been weakest in post-war US economic history.

US investment and consumption have still not recovered to levels relative to GDP seen before the Great Recession.

So my mantra of a Long Depression is confirmed by these figures – even for the US, which has had the best ‘recovery’ of the major capitalist economies.

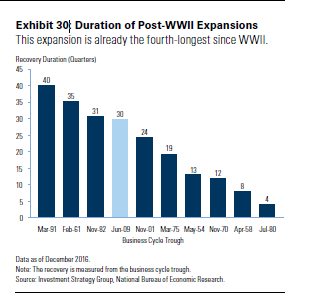

Moreover, the duration of this US recovery is the fourth-longest, at 30 quarters of a year, only exceeded by the recoveries in the ‘golden age’ of the 1960s and the profitability boom periods in the ‘neoliberal era’ after the slumps of 1980-2 and 1991.

So the US is due for another slump on the law of averages, within a year or two.

But all mainstream economic forecasters rule out a new recession in 2017. The mantra is that recoveries ‘do not just die of old age’. Something must happen to stop them. As Goldman Sachs puts it: “Recessions in the US have been triggered by Federal Reserve tightening of monetary policy; by economic imbalances such as the bursting of the dot-com and housing bubbles in 2000 and 2008, respectively; or by external shocks such as the Arab oil embargo in 1973. The first two triggers are unlikely to occur in 2017, and the third, a shock, is not something that we can typically anticipate.”

GS goes on: “Historically, since WWII, the odds of a recession occurring over a 12-month period have been 18%. Our composite recession model, incorporating end-of-year financial and economic data, estimates the probability of a recession in 2017 at 23%.” So slightly higher than average. But “once we incorporate the likely passage of a fiscal stimulus package of tax cuts and infrastructure investments in the latter half of 2017, the probability of a recession this year declines to about 15%.”

The question is whether the optimism of markets and mainstream economists of an extended and permanent boom in global production based on fiscal spending and corporate tax cuts in America is justified. As I have argued in other posts, Keynesian-style policies have miserably failed in Japan to get that economy out of its long depression.

And I have argued that sustained growth depends on increased investment in productive sectors and that depends on corporate profits in the US rising, not falling as they have done up to the second half of 2016. This measure is ignored by Goldman Sachs, although not by others.

Trumponomics, in cutting corporate taxes and delivering tax breaks for infrastructure investment, might boost profits for some sectors. But as the data above show, the vast majority of US corporations are seeing the profitability in their investments falling, not rising. The odds of a new recession may be higher than Goldman Sachs thinks.

“A company’s value is measured by investors by its liabilities (net debt and stock value). Currently, those liabilities are at levels compared to earnings not seen since the dot.com collapse of 2000-1.”

Hey Michael, could you please explain what did you mean by liabilities compared to earnings being at 2000-1 levels? I guess the ratio between liabilities and earnings is at 2000 level. In what sense?

And an observation: I think that valuating (or in Marxist terms pricing) a company is based on a faulty methodology. Liabilities are calculated based on debt (which was incurred in the past) and stock value (which is the expected, i.e. in the future, earnings); it follows that the ratio between net debt and stock value is wrong since it takes two different times: one is the past (which is known) and the other is the future (which is unknown or reflects hopes and desires).

Wouldn’t company pricing be much accurate if liabilities would represent the ratio between future debts (not net debts) required to service company’s operations (including investments, servicing old debts, dividend payments, etc.) and stock value? In this case both variables would be placed in the same time period, i.e. future, reflecting the real weaknesses and strengths of the company.

Last question: why stock price matters so much for the company’s worth in price terms when stocks once issued are traded in the secondary markets with no impact whatsoever in the daily operations of the company? I know that neoliberal economics is about increasing shareholders’ value (i.e. dividends) and stock prices, hence the buying back stock programs, but this so-called economic procedure just reflects the financialization of the non-financial companies (e.g. executives’ compensations tied to the performance of the stock not company’s operations which are implicitly considered acceptable if stock prices go up). However, I find the measure of company’s pricing by measuring its liabilities in two different time spans problematic and it only reflects the desires of their executives to increase their market price than anything else. It reflects the CEOs compensation in stock options (rather than salary) which is also tied to future (expected) earnings (profits) rather than past performance.

“President Xi may have endorsed in 2013 ‘the decisive role of the market,’ but that hasn’t diminished the leading role of the state.” A comparison with the guided capitalism of Japan in its prime to about the 1970s is instructive. The basic similarity is that profit is the dominant criterion. In the case of China, this is obvious for the privately owned corporations and increasingly undeniable for the state-owned ones, too. (Actually, many are partly state owned and partly privatized in various ways, such as the issuance of shares that enshrine maximum earnings per share.)

“In Europe, the PMIs suggest that manufacturing is now expanding at a record pace (from a low level), while the global average PMI has now reached levels not seen since 2013…

The latest monthly estimates show that economic growth has recovered markedly from the low point reached last March. Then fears of global recession were high. But Davies says now “not only were these fears too pessimistic, they were entirely misplaced. Growth rates have recently been running above long-term trend rates, especially in the advanced economies, which have seen a synchronised surge in activity in the final months of 2016.” …

According to Fulcrum, the growth rate in global economic activity is currently running at 4.1 per cent, compared with an estimated trend rate of 3.8 per cent. This represents a vast improvement on the growth rates recorded in 2015 and early 2016, when growth dipped to below 2.5 per cent at times. The latest estimate for the advanced economies shows ‘activity growth’ running at 2.5 per cent, a rate achieved only rarely during the post-crash economic expansion…

Thus, according to Fulcrum, emerging economies are currently growing steadily at close to their 6 per cent trend rate, or 2 percentage points higher than achieved in 2015. They have therefore ceased to be a drag on the global expansion.”

Oh my goodness just look at that, the trolls are wearing no clothes!

If one actually bothers to look at the trends of the data like that on the Eurostat site, rather than cherry pick information, or as Boffy does, make stuff up, then it becomes clearly that despite the “low” proportion allotted to energy in the make up of the EU’s Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices, fluctuations in energy prices, because they have been so dramatic, tend to drive the calculation of inflation rates.

So those of us, naked and/or clothed, who saw in the overproduction of petroleum the driver to inflation have not been surprised that implosion of oil prices, has been followed by a recovery, although to less than half of its previous high, and this recovery has “trickled up” into other sectors. Big deal.

We all know this is a cyclical occurrence within a larger secular or structural trend– the trend being to lower rates of profitability, further attacks on living standards and wage rates, reduced rates of growth, persistent greater rates of unemployment, etc etc.

The troll without any clothes is the one standing in the Boff so to speak; clad in the perpetual sunshine of “capitalist progress” on planet Boffy.

“But the Chinese economy is a weird beast, not understood by mainstream (and even Marxist economists). President Xi may have endorsed in 2013 “the decisive role of the market,” but that hasn’t diminished the leading role of the state. As Aidan Turner put it recently, “Suppose that a full quarter of Chinese capital investment – currently running at around 44% of GDP – is wasted: that would mean China’s people are unnecessarily sacrificing 11% of GDP in lost consumption: but if the remaining 33% of GDP is well invested, rapid growth could still result. And, alongside obvious waste, China makes many high-return investments – in the excellent urban infrastructure of the first-tier cities, and in the automation equipment of private firms responding to rising real wages.” ”

This is where I part company with “economists” of all stripes, and perhaps even with Michael… the argument presented here being that if “rational” investment policies are followed and funded massively enough, whatever that mass may be, then supposedly the conflicts, antagonisms, and breakdown of accumulation can be averted, recovered, eliminated.

That’s just not how capitalism works; and certainly not how the Chinese economy works. The argument presented by Turner is essentially one of “rationally” developing a domestic market so that “productive investment” counters the “excesses” of private capitalism. It is essentially and Keynesian argument, and an argument essential to Keynes.

Capitalist investment, “rational” or “irrational”– planned or laissez-faire always encounters the same conflicts. Overproduction really does exist; overproduction beyond the ability of markets to return adequate levels of profit is inherent in capital accumulation; problems with the realization of surplus value are real, and are not to be dismissed as “underconsumptionist” arguments.

The problem with capitalism is not that it “under-invests” or “over-invests” or that it creates fictitious capital rather than “productive” capital– as if capital has any productivity in itself rather than plagiarizing the productivity of labor. The problem is that capital invests as capital; the problem is that accumulation and the continued appropriation of value, in both mass and rate, reach an impasse. Throwing more investment on top, as was done in the maritime industry recently only reproduces the impasse.

I agree. Moreover, investing more is likely to accelerate contradictions. While the capitalists may adjust their sales to more expensive products and compensate for inequality of wages, innovation may cripple the ability of to make products with high prices since stuff will be made with a very short amount

of human work, and not offer any meaningful addition to value of use. For example, the CPUs new desktop computers are not significantly fast, or having new capabilities, than 5-6 year old CPU. The same is happening to other components.

The same is due to happen to market segments that do not rely on heavy machinery (which are much easily damaged due exposure to environment). There are self driving cars, but that’s not due faster computers, but the miniaturization of many components that are used to check the environment and the advance of programming techniques.

Also, no matter how smart is the person, advancing science requires more and more people working in parallel

and also with precision. It is a thing of diminishing returns. Discovering things is like looking for stuff in the darkness. And to make it into a product, you have to put several new things working together. So, discovering is more and more expensive. It might get to the point (not sure) where capitalism won’t be enough to elevate the production forces, that is, it won’t be profitable to develop new use values that actually improve people’s lives, and only a coordinated effort to educate people and make them study as much as possible, will be the path to discover new things.

The market segment that might hinder that is warfare, since it still uses a lot of labor to guarantee the quality of things, and so it is still sort of legging behind everyone, given the quantity of money invested on it.

Consider the November jobs report. We were told that the unemployment rate has fallen to 4.6% and that 178,000 new US jobs were created in November. The recovery is on course, etc. But what are the real facts?

The unemployment rate does not include discouraged workers who have been unable to find employment and have ceased job hunting, which is expensive, exhausting and demoralizing. In other words, unemployed people are being pushed into the discouraged category faster than they can find jobs. That is the explanation for the low official unemployment rate. Moreover, this reported low rate of unemployment is inconsistent with the declining labor force participation rate. When jobs are available, people enter the work force in order to take advantage of the employment opportunities, and the labor force participation rate rises.

The reporting by the financial presstitutes adds to the deception. We are given the number of 178,000 new jobs in November. And that is it. However, the data released by the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows many problematic aspects of the data. For example, only 9,000 of the claimed 178,000 jobs are full time jobs (defined as 35 hours or more per week). October saw a loss of 103,000 full time jobs from September, and September had 5,000 fewer full time jobs than August. No one explains how an economy losing full time jobs is in recovery.

The age distribution of the November new jobs is disturbing. 77,000 of the jobs went to those 55 and over. Only 4,000 jobs went to the household forming ages of 25-34.

The marital status distribution of the jobs is also troubling. In November there were 95,000 fewer employed married men with spouse present and 74,000 fewer employed married women with spouse present than in October. In October there were 331,000 fewer married men and 87,000 fewer married women employed than in September.

http://www.paulcraigroberts.org/2017/01/03/can-trump-fix-the-economy-in-2017-paul-craig-roberts/

Meanwhile in Britain

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-38528549