Marx’s law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall (LTRPF) argues that, over time, the profitability of capital employed will fall. Marx reckoned this was “the most important law of political economy” because it posed an irreconcilable contradiction in the capitalist mode of production between the production of things and services that human society needs and profit for capital – and it would generate regular and recurring crises in investment and production.

Marx’s law has been attacked theoretically as erroneous, illogical and indeterminate and it has been rejected as empirically disproven. However, various Marxist economists have provided a robust defence of the law’s logic. (Carchedi and Roberts, Kliman, Murray Smith.) And the body of empirical evidence supporting a long-term falling rate of profit on capital accumulated has mounted over the years.

Now Tomas Rotta from Goldsmith University of London and Rishabh Kumar from the University of Massachusetts have made another important contribution to the empirical evidence supporting Marx’s law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall. In their paper, Was Marx right? Development and exploitation in 43 countries, 2000–2014, R&K find that Marx’s law is right: capital intensity rises faster than the rate of exploitation and so the global profit rate declines.

They generate a new panel dataset of the key Marxist variables from 2000 to 2014 using the World Input Output Database (WIOD) covering 56 industries across 43 countries in the 2000-2014 period. “To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first ever attempt at producing a comprehensive global dataset of Marxist variables.”

R&K find that the average profit rate declined at the world level from 2000 to 2014. They add that the rate of profit on total capital declined as per-capita GDP for a country rose owing to the greater share of unproductive capital in rich countries. Given that unproductive activities increase with economic development, “our finding adds a second mechanism to Marx’s original prediction about the falling rate of profit.”

The big advantage of the R&K’s study is that it can produce a rate of profit based on the productive sectors of economies. In Marxist theory, it is only these sectors that generate new value from capital investment and not just redistribute value already created. So it is the rate of profit in these productive sectors that best indicates the health and direction of the capitalist economy; as the rate of profit in the non-productive (financial, retail, commercial and property) sectors ultimately depends on the rate of profit in the value-creating productive sectors.

R&K point out that previous estimates of the rate of profit at a global level could not make this distinction (Basu et al. (2022) https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2020/07/25/a-world-rate-of-profit-a-new-approach/ ). But using industry-level data from the Socio-Economic Accounts (SEA) of the World Input-Output Database (WIOD) and country-level data from the Extended Penn World Tables (EPWT), R&K recalculate the value added of every industry using the decomposition between productive and unproductive activity.

They find that the global rate of profit on both total and private capital reached a peak at 13.7% just prior to the 2008 financial crisis, then plummeted and continued a gradual decline to 12.7% in 2014 (graph top left). This was accompanied by a rise in the organic composition of capital (the ratio of fixed assets and raw materials to wages of labour) – graph bottom left, which rose faster than the rate of surplus value (profits over wages) – graph top right – all in accordance with Marx’s law of profitability. And this overall fall was driven by a fall in the rate of profit in productive sectors (graph bottom right).

“The increase of 12.4% in the rate of surplus value suggests that the decline in the global rate of profit was driven by a larger increase in capital intensity. The productive capital-labor ratio rose 25.8% (from 314% to 395%) while the total capital-labor ratio rose 16.8% (from 763% to 892%) over 2000–2014. The decline in the world rate of profit was therefore driven by the faster growth of the global c/v compared to the growth in s/v, as Marx expected.”

Another advantage of R&K’s dataset is that it enables the decomposition of the Marxist variables for the rate of profit within countries and between countries. They find that “in just 15 years, China rapidly increased its weight in global value added from 5.3 to 19.3%. Concurrently, the weight of the United States in global value added fell from 30.1 to 22.3%, and Japan’s weight shrunk from 16.3 to 6.7% in the same period. Although the shares are smaller, there is also a rapid downward shift for Germany from 6.6 to 6.0%.”

China also became the country with the greatest share of the global capital stock in productive activity, rapidly increasing its weight from 6.0 to 23.6%. This compared to a fall of the United States’ weight from 24.8 to 17.4%, Japan from 21.2 to 8.8%, and Germany from 6.5 to 4.6%. Not surprisingly, the United States dominated the shares of global income and capital stock in unproductive activity i.e. finance, real estate and government services. The US and the UK are increasingly ‘rentier economies’, living off the new value created in China and other major productive economies.

According to R&K, following Marx, the advanced capitalist economies should exhibit higher rates of surplus value, higher organic composition of capital and lower average profit rates. And yet, they found that the rate of surplus value is higher in poor countries. Their answer is to this is that the level of wages is much higher in the rich countries compared to wages in the poor countries – a differential that is sufficient to make the rate of surplus value higher in the latter. “Wage rates per hour are an order of magnitude higher in rich countries: while the ratio of labor productivity between India and USA is 5%, the ratio of wages is only 2%. Thus, being a worker in India implies substantially lower wages than being a worker in France or Germany.”

This is similar to the explanation that Carchedi and I made in our paper on modern imperialism, where we also found a higher organic composition of capital in the imperialist economies, but also a higher rate of surplus value in the periphery. (see graph below, top left). However, R&K reckon this outcome provides empirical support to the super-exploitation thesis of Ruy Mauro Marini and others. But I don’t think this follows.

Low wages do not have the same meaning that Marx gave to ‘super-exploitation’. He defined that as when wage levels are below the value of labour power, which would be the amount of value necessary to reproduce the labour force. As argued at length in our book, Capitalism in the 21st century pp134-140, average wage levels in poor countries do not have to be below any value of labour power to lead to higher rates of surplus value in these countries.

R&K find that richer countries have lower profit rates which they argue is due to the greater stock of fixed capital tied up in unproductive activity in the rich countries (graph bottom right). This is because the data show a higher rate of profit on productive capital in rich countries (graph bottom left).

All these results are a valuable contribution to supporting Marx’s law of profitability. But R&K’s approach has limitations. As they point out, the time series using the WIOD is very short, just 15 years from 2000 to 2014. But more important, input-output tables have some theoretical disadvantages as they measure inputs and outputs (whether in money or labour terms) in the same year, like a snapshot. They do not measure production prices and profit rates dynamically. That’s where the Basu-Wasner data using the EWPT database (see above), although it cannot distinguish between productive and unproductive sectors, has an advantage in indicating changes and trends over time.

And there have been attempts to use national data to generate rates of profit for productive and unproductive sectors. Tsoulfidis and Paitaridis (T&P) did so here. Their results for the US show that, in the 1990s, there was a rise in the overall (gross) rate of profit in the neo-liberal period from the early 1980s to the end of the 20th century, but the rate of profit in the productive sectors (net profit rate) of the US economy did not rise and capitalist investment went more into unproductive sectors (finance and real estate).

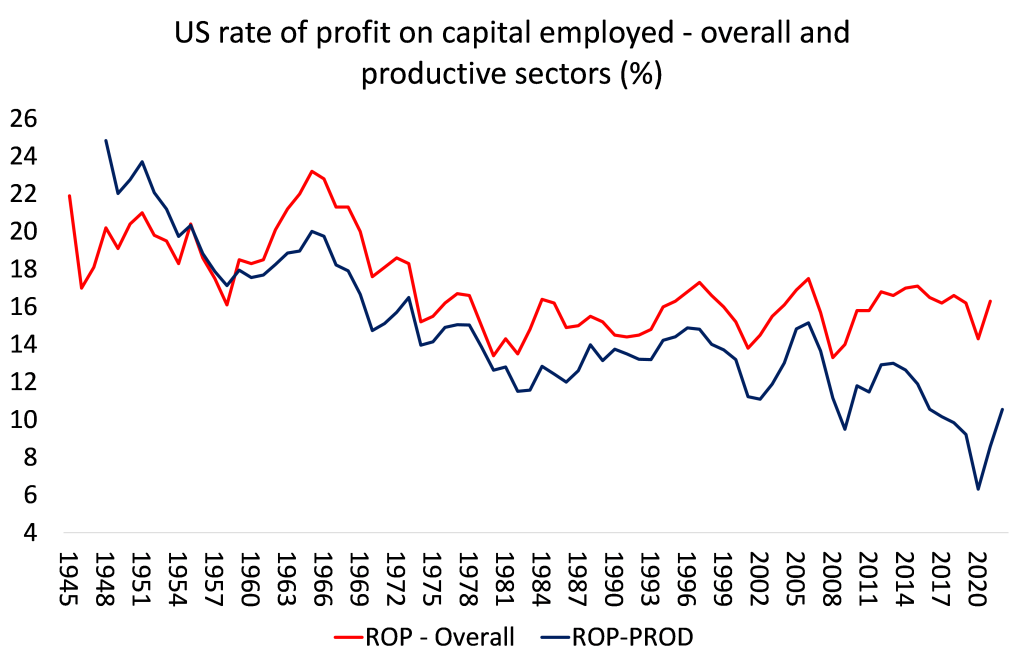

In a recent piece of (unpublished) work by me , which also breaks down the rate of profit between the productive sectors (using similar categories as R&K) and the overall US economy, I get a similar result to T&P. The gap between the ‘whole economy’ rate of profit and the rate of profit in the productive sectors widened from the early 1980s. The overall rate has been pretty static since 1997, but profitability in the productive sectors, after rising modestly in the 1990s, has fallen back sharply since about 2006. US capitalists are finding better profits in unproductive sectors. That damages productive investment.

But these results are for the US only. Only R&K have produced, as they say, the first set of Marxist variables that distinguishes the productive from the unproductive sectors for the world and thus throws more light on the health of capitalist production – an important step in the empirical work supporting Marx’s law.

Gracias Michael por insistir en este asunto crucial (las evidencias sobre la ley de la rentabilidad de Marx). Mi comprensión lectora de la lengua inglesa es limitada, por ello utilizo habitualmente el traductor. Supongo que somos muchas personas de habla española (en España como mi caso, o en América Latina) que nos gustaría poder leer en español (castellano) tus últimos libros en colaboración con Carchedi. Me gustaría saber si hay alguna gestión para poder publicarlos pronto en español. Gracias y saludos

Querido Gerardo

Actualmente estoy escribiendo un libro que se publicará en español y cubrirá todos los temas importantes de la economía mundial, pero no lo publicaré hasta finales de este año. Pero mientras tanto intentaré hacer algunas cosas para los lectores españoles.

Professor Roberts, in my case my mother tongue is also Spanish, so I am also very happy to receive the news of the forthcoming publication of a book of yours in Spanish. I have read your book “The Long Depression” and I follow you in the blog, besides contributing to the diffusion of the different posts you publish in it. I believe that today you are the most important Marxist economist alive.

Greetings from Spain

Your review is disappointing. In correspondence I pointed out that this sterling piece of work is deeply flawed. That means it is non-Marxist. The rate of profit they use is profit divided by fixed capital and annual compensation. Annual compensation is not variable capital. Dammit, even capitalist accountants know the difference in so far as they understand that working capital does not need to cover a year’s wages. The capitalists may be a lot of things but parking three or four times as much money as is needed to pay wages, is not one of them.

This article ignores turnover. And because it does so it comes to the erroneous conclusion that the rate of profit did not recover post 2008. But turnover accelerated post 2008 and up to 2013 /4, so while annual compensation rose, variable capital did not. The result was a sharp recovery in the actual rate of profit up to 2014. But this cannot be admitted because so much has been written that it did not, making it a question of reputations rather than reality. But without understanding this rise then fall in profit from 2015 onwards, we cannot explain why globalisation faltered, not after 2008 but after 2016. All the evidence points to that.

Another aspect is important to consider. The gap between the value of variable capital and annual wages is far bigger than the gap between the value and cost of productive and unproductive labour. Its like stepping around a puddle of water on the side walk only to be drenched by a passing car.

So let your readers decide. Here is the link to my critique which shows the divergence in the actual rate of profit from that of a rate based on annual compensation. http://theplanningmotive.com/2024/01/02/yet-another-valuable-piece-of-research-invalidated-by-using-annual-compensation-instead-of-variable-capital/

And for those who want a quick primer on the turnover formula follow this link. http://theplanningmotive.com/an-introduction-to-the-turnover-formula/

Honestly Michael you have to make a decision, to remain locked up with the rest of Marxian Academia ignoring turnover and who are trapped in the 1970s, or to embrace Marx’s methodology in the round. Perhaps we can debate this here. You owe that much to you readers.

I fail to see how faster turnover rates would generate false data. Whatever the speed of turnover, it would still be all calculated yearly, so a faster turnover is simply itself multiplied by how many times it fits in 365 days. The data of these world tables are almost all calculated yearly or quarterly, which is the same (a quarter is merely an year divided by four, i.e. three months).

Higher turnover also doesn’t affect the calculation of variable capital and the OCC. The composition of capital is checked every rotation, so, e.g. a 40% variable capital rotated twice at the same time will still be 40%; it’s literally 40% used twice. So, if you hasten the time of rotation by two, you are doubling the profit rate (therefore, also the surplus rate) — but you can only know that because you already knew the OCC (therefore, the variable capital), which remains invariable.

Your claim over the “two gaps” also don’t seem to make much sense. Variable capital can only be calculated in wages (i.e. money); how do you know there is a “gap” between wages and variable capital, if variable capital is expressed as the sum of all wages? Sure, you can say a plumber in India earns half the wages of a plumber in the USA, but that would only mean the rate of surplus value in India is double the USA’s, not that there is a “gap” for the Indian plumber. Even then, how much is this “gap” for the American plumber (if there is one)? Even if you accept that this “gap” is this “compensation” (I imagine you’re referring to the wages of the unproductive sector), it is simply a case of redistribution of surplus value, not of a “gap” between hours worked and wages received, which is the surplus value (profit is surplus value by another name), not the “gap”. If it is surplus value, than we can already see it in the R&K graphs, we don’t need to readjust for “compensation”.

VK the turnover time in 1850 was 365 days, in 1950 it was 365 days and in 2023 it will be 365 days. In other words it is invariable. Turnover times are variable based on technical changes and market changes due the business cycle. For instance if annual compensation amounts to forty billion a year and turnover is four, then variable capital is only ten billion. So ten billion passes from capitalist to worker and from consumer back to capitalist on capitalist on average every three months. According to your logic this means variable capital adds up to forty billion over one year and even eighty billion over two years then 120 billion over three years. At this rate the capitalists would be bankrupt in no time and we could all luxuriate in a communist society. You of all people, who ably defended dialectical thinking now stands accused of linear thinking.

Do forgive me if I accuse you of sophistry. You really should go back and read up what Marx and Engels said about turnover and it’s importance.

UCB’s argument has a base in Marx’s writings in Vol 2 where Marx makes the point, almost offhandedly IIRC, that the revenue realized in a turnover cycle essentially frees the capitalist from making a fresh outlay for “v” (and I would argue also frees the capitalist from making a fresh outlay for any and all of the components of circulating capital).

How this impacts the overall ROP or the FROP is not that clear to me, since (1) we expect all the different circulation times to be “homogenized” in the attempt to achieve the average rate of profit (2) the compulsion to decrease circulation time and reduce the lag between value expropriation and its realization compels capitalists to increase fixed investments in transportation and communication such that the positive impact in decrease in turnover time is offset by the increased OCC, amplifying the tendency of the rate of profit to decline. (Used to be a “leading indicator” on Wall Street was/were sales of telecom equipment and trucks to industries) (3) UCB’s own charts, graphs, etc. plotting the ROP closely parallels the values established by others who do not account for the turnover time.

I think UCB’s points are valid, and I think their real significance could be in giving us a more precise look into the inflection points in the ROP- when the rate peaks, stumbles, and falls

@ ucanbepolitical

Yeah, no, your argument is pure insanity.

It doesn’t matter what word you choose — turnover and compensation instead of rotation and wages — the worker always operates through simple reproduction C – M – C. Here the unit of time is irrelevant: could be one year, could be ten years, could be one million years. The worker, as a class, must always spend everything it receives.

If reproduction is simple, it doesn’t matter if it is ten, fourty, eighty or 120 billion USDs, it will all go back to the capitalist class at the end of any rotation or cycle, regardless of the nature of the cycle (if it business, inventory, fixed capital, Kondratiev etc. etc.). It also doesn’t matter what the socially necessary labor time and the rate of surplus value are (which you call the “technical and market changes”): the resultant vector for the working class will be always null.

What I think you’re confusing is the speed of money. But the speed of money is not value creation, it’s just that: money circulating at a certain speed. The capitalist can use the same money to pay his worker more than one time: he doesn’t need to pay him or her with newly minted money every time there is a “turnover” of variable capital.

P.S.: why are you obsessed with the argument that the profit rate only started to fall after 2016 and not 2008? What is so important to you about this short, eight year period of time?

Excellent article!!!

MR writes that his and Prof Carchedi’s analysis takes them to a point “where we also found a higher organic composition of capital in the imperialist economies.” Do those studies concentrate on productive sectors of the imperialist sectors?

If so, they seem to contradict Rotta and Kumar’s paper in which they argue that the OCC rate is lower in the “advanced countries” along with the rate of surplus value, yielding a higher rate of profit on productive capital in those same countries. (FWIW, I agree with Rotta and Kumar, the rate of surplus value declines in the “more developed” countries since “v” does not experience a rate of decline steeper than that of total labor time).

I also think we need a better categorization of finance capital than simply “unproductive.” First, Marx explicitly states that interest is an allocation from the total surplus value. It is not a deduction from the total surplus value. Now suppose Hapag-Lloyd self-finances the construction of a containership– the money advanced is productive capital. Two years later, Hapag -Lloyd floats a corporate bond offering to finance 10 containerships. The bonds are underwritten by JP Morgan Chase and bought by pension funds, investment banks, hedge funds etc. Is the capital raised in those markets now “unproductive”?

We need to account for the interest payments made by the productive sector as part of the surplus value generated in production, but distinguishing that stream for the profits generated by and in options, futures, currency etc markets is not an easy task.

R&K are basically arguing that the advanced capitalist nations are deindustrialized: the graphs in the post are too small to read, but it seems they have, in this era (2000-2014) more profitable productive capital and lower OCC than China and friends (the Third World), but, since they (the advanced ones) have huge unproductive sectors, their overall profit rate (social profit rate) is still lower than the Third World’s.

The Third World tries to compensate this “unbalance” (which is the tendency itself) by lowering their wages. Hence the rate of surplus value is actually higher there than in the First World.

But, taken capitalism as a whole (worldwide), the profit rate still falls, overcoming the titanic effort the capitalist classes of the Third World make to lower the wages of their working classes, therefore confirming Marx’s law.

I think the OCC for the imperialist economies has been rising but as T&K show that may not be the case for the productive sector. It seems that investment in fixed assets etc has been switched to unproductive sectors like real estate, commerce, retail, government. Unequal exchange in international trade means the transfer of surplus value from the lower technological countries to the higher ones. This transfer applies to the whole economy not just the productive sector.

If a productive sector capitalist invests in containers and raises the money needed by borrowing, then the investment is still productive. But now the surplus value appropriated does not all go to the productive capitalist as debt servicing payments must be made to the finance capitalist. So surplus value get divided up between profits of enterprise, interest and rent. Total surplus value is created by labour power and appropriated in the productive sectors but then surplus value is distributed to unproductive capitalist sectors, reducing profit available for the next round.

“surplus value is distributed to unproductive capitalist sectors, reducing profit available for the next round.” Surely you don’t mean this. One of the major activities of the financial sector, and of rentiers, is that they make investments or lend the money out for investment. This activity does not reduce the profit available.

Financial sector funds for lending come from previous surplus value created in productive sectors and gained by the financial sector through interest charged on loans or bonds in the productive sector. New loans to the productive capitalists become part of capital employed by productive capitalists. The productive capitalist must then appropriate new surplus value and pay some of that back to the finance capitalist. Thus the productive capitalist does not keep all the surplus value appropriated from the value created by labour.

Also much of financial sector funds do not go back as loans to productive but are used in purchasing financial assets and speculating in these ie fictitious capital which is not part of capital at all.

There is a bigger issue, within every productive corporation lies an unproductive sector, employees engaged in office work falling under the heading of SGA or selling, general and administrative expenses. If they are in-house expenses and not outsourced it is virtually impossible to separate them out in the national input-output tables. There is another issue. Productive corporations are generally the ones producing things which need to be distributed. The discounts they provide which fund the distribution chain are invisible but that said they tend to affect the financial accounts in the parent country where these accounts are compiled as consolidated accounts again making international comparisons difficult. Unfortunately discounts have tended to be ignored by many Marxian analysts.

In the end it does not really matter, what matters is the eventual rate of profit which nets all the transfers of value in and out of the corporation, provided of course that rate of profit is calculated scientifically.

This is an excellent article. It’s a great basis for thinking about global events.

What about AI and new technology as factors the tendency of the rate of inflation profit to fall? Surely that means variable capital being suppressed in favour of constant capital. Profit making companies like Amazon would prefer to robotise work forces (real living labour) and intensify their exploitation in the west rather than replace them with AI??? Paula

The theory of labour according to which living labour is the only source of surplus-value has consequences because it implies that with the technical improvement of labour productivity, the working time of the working class will not diminish but will become increasingly superfluous to the production of material wealth. So instead of reducing the working time of the working class, the capitalist mode of production gives rise to a new special category: superfluous working time.

1. Where do the profits of financial firms come from? Trace that back while remembering that all profit is surplus value at its source, and the neat distinction of accounts between productive and non-productive sectors falls apart.

2. “China rapidly increased its weight in global value added from 5.3 to 19.3%.” Can we state this bluntly: exploitation of the Chinese working class has been a bonanza for both Chinese and Western capital.

1. The general formula for fictitious capital, according to book III of Das Kapital, is: M – M – C -…P…- C’ – M’ – M’. So every profit of the fictitious capital comes from productive capital. Of course that, in the cases where the bank lends directly to a worker, it is extracting surplus value directly from the source, but even this falls into Marx’s scheme, because a worker only generates surplus value in a context — the context of working for a productive capital.

2. Data indicates that, during the neoliberal era (1980s-2008), it was not only China, but the entire Southeast Asia (I’m including here all the Asian Tigers, including South Korea, in this group, to simplify) that kept capitalism’s productive base “afloat”. i.e. Southeast Asia was the only area of the world we can state truly boomed during the 1980s and 1990s — China being simply the biggest country of the group. However, China only started to truly boom after 2001. After Xi Jinping’s taking office of China (2012), we entered an era where the West started to openly treat China as a threat to their civilization, i.e. capitalism. So, this is my personal take on this: The West truly exploited — and fully benefitted — from China’s cheap labor only during Deng Xiaoping’s and Jiang Zemin’s era (roughly speaking) (1978-2001). After that, there was a period of rapid transition (Hu Jintao’s era) in which China finished climbing the proverbial hill until the era we’re living today (Xi Jinping), where China is quickly becoming more independent from the capitalist grip on its economy.

Dear Michael,

Thank you very much for writing this blog post about our paper. Much appreciated.

Rishabh and I also computed several robustness tests using different classifications of productive and unproductive activities. Our empirical results are valid across different productive-unproductive classifications. There was no room to publish these robustness tests in the paper, but they are available on my website, if anyone is interested:

regards,

Tomas Rotta

THANK YOU, IT IS GRE