ASSA, the Alliance of Social Science Associations, holds the biggest annual economic conference in the world. It is hosted by the American Economics Association and this year was held in San Antonio, New Mexico. Over 13,000 economics students and professors attend and hundreds of papers are presented in sessions over three days. And there are addresses by the ‘great and good’ of mainstream economics, attended by hundreds. But also, there are sessions organized by radical economics group, attended by handfuls.

Let us start by discussing some of the mainstream economics sessions. I reckon we can single out three main issues taken up at the big meetings: the state and future of the US economy; why there was an inflationary surge after COVID; and whether climate change and global warming can be curbed or stopped.

One session was entitled: Where is the economy headed? The panellists in this session expressed ‘uncertainty’ about the direction of the US economy over the next few years because of the ‘jolts’ from the COVID pandemic and its impact on commercial real estate (home working), possible banking crises and ‘geopolitical instabilities’. “These instabilities, in particular, make the path forward less predictable and less resilient to systemic shock.” said Janice Eberly of Northwestern University

What was surprising is that the panellists seemed most worried about the size of the public debt and fiscal deficits weakening the US economy. It seems that the mainstream is still obsessed with reducing the size of the public sector and spending, rather than addressing any faultlines in the dominant capitalist sector of the economy. James Hines of the University of Michigan forecast that by 2030 the cost of servicing the public debt (interest and bond repayments) would exceed all tax revenues and then there would have be cuts in public spending – even defence spending (shock!). And this was the real obstacle to growth in the US economy.

The comforting thought, however, Hines said was that the US “does capitalism” better than any other country, with strong entrepreneurial companies and well organised financial and public institutions to ensure that US capitalism works. “Most of the things that are going to be helpful are going to come from free markets—lots of trade, lots of investment,” said Hines. What about the high and rising inequality of income and wealth in the US?, a questioner asked. Yes, this was concerning was the reply, and economists needed to consider the problem carefully…. but no answer was offered.

Then there was the question of artificial intelligence – would this provide a new boost to productivity and take the US economy up and away? The panellists were cautious, pointing out that often technology innovations remain confined to their sectors and do not diffuse across the economy. However, sometimes, the current equilibrium can be ‘punctuated’ by a disruptive innovation that transforms the economy, said Eberly (by the way the use of the term ‘punctuated equilibrium’ comes from the paleontology work of Steven Jay Gould and Niles Eldridge, who argued that things don’t change just gradually, but sometimes can leap forward.

In another session on the US economy, Glenn Hubbard, former economic adviser to the Trump presidency, was hopeful that AI would be a big boost to US growth, but much depended on getting public finances under control and reducing unnecessary regulation of industry and finance. In the same session, the well-known ‘debt’ economist, Kenneth Rogoff reckoned the AI could overcome the productivity growth slowdown that the US and other major economies are suffering from but such a ‘turning point’ would also depend on avoiding a debt crisis especially in developing economies engendered by high interest rates imposed by central banks in the ‘fight against inflation’.

And indeed, the cause of the post-pandemic inflation burst dominated many mainstream sessions at ASSA 2024. In one big session, attendees were presented with every possible mainstream theory on the cause of inflation.

“We didn’t really understand why inflation spiked in the first place. So maybe we shouldn’t be surprised that it came down faster than we thought, too,” said Hines. There is now a wide body of evidence that the inflationary spiral from 2021-23 was mainly cause by supply blockages and the poor recovery of production and international trade in goods, as well as by companies in key sectors taking the opportunity to hike their prices in order to preserve profit margins.

But nearly all the presenters in this session spent their time trying to find other reasons for the inflationary spiral, sticking to their old mainstream theories that inflation is caused by ‘excessive demand’ generated either by too much money being injected into the economy (monetarism) or by too much government spending (austerianism); or in the case of the Keynesians by tight labour markets driving up wages.

Take the Keynesian case. A leading Keynesian macroeconomist Gauti Eggertsson from Brown University did his best to revive the failed Phillips curve, namely that if unemployment falls towards full employment, this will push up wages and that will lead to increased inflation. Eggertsson agreed that the traditional Phillips curve did not apply to current inflation, BUT, you see, the curve has become ‘non-linear’ ie unemployment can fall straight down without any impact on inflation and then suddenly turn a corner and inflation jumps. That’s why you can get full employment and no inflation for much of the time – until now.

Eggertsson agreed that it was ‘supply-side shocks’ that caused inflation to rise and now that the supply-side blockages have receded, inflation rates have fallen. But he wants to save the Keynesian theory as well, by arguing that lower inflation has only been possible because of a ‘non-linear’ Phillips curve. Ironically, the reverse of the non-linear curve is that any new supply blockages could cause a sharp spike back up in inflation rates.

Whether you agree with the Keynesians’ attempt to preserve their labour market theory (and it is hard to do so, in my opinion), given that wage rises never kicked off inflation in the first place and always fell behind the inflation rate until recently, it is another argument against the monetarist view that the Federal Reserve adjustment of interest rates had any effect on reducing inflation in the last year.

Yet the monetarists were still present at ASSA. One of the most famous is John Taylor, author of the Taylor rule which supposedly sets limits on how to avoid inflation or unemployment by manipulating the ‘right’ interest rate to be set by the Fed. At ASSA, Taylor told his audience that the inflationary spiral was due to the Fed being too lax on hiking rates even before the pandemic and not following his Taylor rule. Then they hiked and now they should reverse.

Then there are the ‘Austerians’. They argue that the inflationary burst was caused by ‘too much’ government spending. Governments ran annual budget deficits and so drove up debt levels and this generated ‘excessive demand’ that was not productive for growth and also made Federal Reserve interest rate policy ineffective.

Robert Barro, a conservative economist from Harvard, who has always been obsessed with reducing government spending which he sees as ‘crowding out’ the private sector, presented evidence for 37 OECD countries that “fiscal expansion underlies the surge in inflation for 2020-2022.” In my view, this is a classic case of not recognizing the causal direction. Fiscal spending relative to output rose sharply during the pandemic because economies were closed down. When economies begin to recover, the size of budget deficits compared to GDP will fall (and they have). What Barro also argued was that the Fed’s high interest rates policy would not reduce inflation but just provoke banking crises as in last March and “a recession by 2024, likely mild unless the financial crisis turns out to be severe.”

Christopher Sims from Princeton University also promoted this ‘fiscal theory of inflation’ as against the Keynesians. He argued that since 1950 the US had suffered three bouts of high inflation and they were caused by ‘fiscal expansions’: it’s overspending by governments that causes high inflation, not lax monetary policy (a la Taylor above).

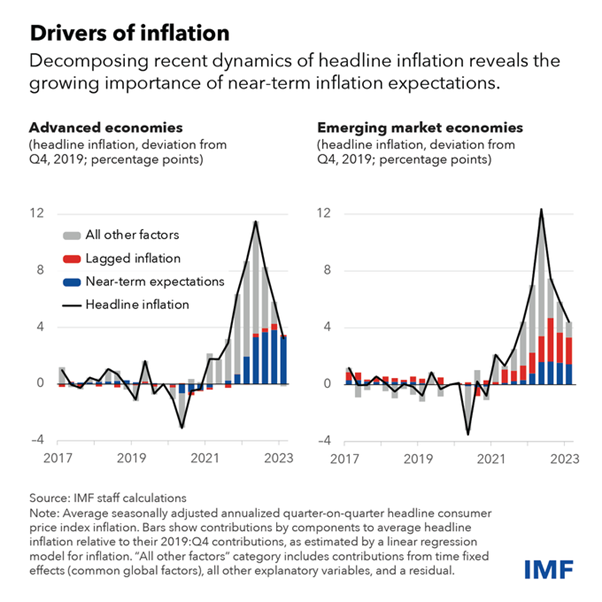

Finally, there was the ‘trendy’ theory of inflation expectations. The IMF under director Gita Gopinath, having seen that monetarist, fiscal and Phillips curves theories don’t explain the recent inflation, have turned to ‘inflation expectations’. The idea is that people think prices are going to rise and so buy more things, thus causing ‘excessive demand’ and thus rising prices. In a recent blog, the IMF economists claim that since 2020, ‘near-term inflation expectations’ have been the biggest driver of price increases in advanced economies and the second biggest factor in emerging markets.

At a special lunch session, MIT professor Ivan Werning gave a long presentation trying to show that inflation expectations played the most important role in boosting recent inflation. His conclusion was that rising inflation was caused by consumers ‘overshooting’ their expectation of price rises and so delivering the very thing they were trying to avoid. So rising inflation is the result of ‘irrational expectations’ by consumers. Thus the theory of inflation is reduced to psychology.

But if you look at the IMF graph above closely, you can see that ‘other factors (ie supply blockages) were the main factor kicking off rising inflation and ‘expectations’ only came later, once people realized that prices were going to continue to rise sharply. Expectations follow real causes. As Keynesian Larry Summers summed it up recently: “The theory to which many economists are gravitating to is that the Phillips curve is basically flat, inflation is set by inflation expectations, and inflation expectations are set by the people who form inflation expectations. And that’s a little bit like the theory that the planets go around the universe because of the orbital force. It’s kind of a naming theory rather than an actual theory. So I think inflation theory is in very substantial disarray, both because of the Phillips curve problems and because we don’t have a hugely convincing successor to monetarist-type theory.”

In his presentation, Werning attempted to come up with an inflation theory that covered all the bases. It all starts with too much demand caused by too much money injections from the central bank and by too much government spending. Then there are various rigidities (monopolies, trade unions etc) that push up prices and by energy price shocks; and finally inflationary expectations.

This cocktail of causes leaves with us with no explanation at all. No wonder Werning summed his address with the words: “that often we end up knowing less than we knew before” but that’s science for you.

The other mainstream debate was around climate change and global warming. The main mainstream method of estimating the impact of global warming on economies has been by what are called Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs), first developed by Nobel prize winner William Nordhaus. And the main policy answer is to introduce carbon pricing and taxes. I have discussed the merits (or not) of IAMs and policy solutions in previous posts. But nothing has changed among the mainstream at ASSA 2024. These are still the methods and policies advocated.

On the method, Steve Keen, a heterodox economist, has produced a blistering critique of IAMs and how they understate hugely the impact on global warming on economies and the planet. See this latest piece by him. For example, (from Steve Keen), the IAM “assumed that empirical relationships derived from data on change in temperature and GDP between 1960 and 2014 can be extrapolated out to 2100—thus assuming that 3.2°C more of global warming won’t alter the climate!: They have assumed that tipping points—critical features of the Earth’s climate such as the Greenland and West Antarctic icesheets, the Amazon rainforest, and the “Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation” which keeps Europe warm today—can be tipped with only minimal additional damage to GDP”.

As for policy, as we well know after COP28, nowhere near enough is being done by governments or companies to stop the accelerating rise in global warming and its impact on the planet. That’s because sustaining the fossil fuel industry is more important than sustaining species on the planet and living standards for the majority. of humanity. There was nothing at ASSA mainstream sessions that recognised this.

“On a level plain, simple mounds look like hills; and the insipid flatness of our present bourgeoisie is to be measured by the altitude of its great intellects.” – Karl Marx

Those psychological theories of inflation cannot be right, because, even when they don’t fall into circular logic (and, with enough philosophical sophistication, one can do so), it doesn’t survive the empirical test, which Marx has already exposed to us in book I.

The worker survives on simple reproduction C – M – C. That means the worker always has a finite amount of salary to spend, and always has to spend it all before he or she starts to work again (philosophically speaking, at the level of the essence of what being a worker really means).

That means that, no matter the expectation of the worker — both individually and as a class — he or she has a finite amount of salary at any given point in time (even when it is zero, because being a worker is a social relation) and all of it must be spent at the end of the worker’s cycle. Psychology is irrelevant here because the working relation is concrete.

The only analysis we “can” (and that’s being very creative) extract from here for the purposes of inflation theory are the three hypotheses of the synchronicity of the worker’s cycle: 1) the cycle is perfect (every worker spends all its wage the day it receives it); 2) the cycle is advanced (every worker is indebted until the day it receives its wage to pay it off entirely) and 3) the cycle is delayed (every worker spends less than it receives from wages; i.e. there is a net saving). But even those considerations don’t take into account fictitious capital (worker is permanently indebted because it purchased a financial product at a bank, i.e. a debt), and the special status of the commodity labor power (we would have to assume zero rate of exploitation of labor), so the premise is extremely weak, not to say unsustainable. This also disproves any theory of wage inflation — another case where a philosophical generality in Marx elegantly solves a seemingly complex problem in another area of science.

However, the scenario becomes clearer when we analyze it from the point of view of the capitalist class. Contrary to the working class, the capitalist class can reproduce amplified, M – C – M’. If you reproduce in an amplified manner, money and commodity vary, opening a path to an “inflation theory”.

Addendum: since Gita Gopinath states, if the quote in this blog post is precise, that, by “expectation” she refers to all humans on Earth and not only the capitalists (“people”), it is patent that, when we descend to the empirical world, she must be talking about the working class because it is the working class that comprises the crushing majority of humankind (even jobless people are working class, because they make the industrial reserve army).

That means Gopinath’s theory is essentially a wage inflation theory — as are basically all other psychological inflation theories (maybe with the exception of some random guy who only talks about the financial sector, i.e. finance=capitalism, but I can’t see the utility of that, since, for fictitious capital, inflation is better treated as an alien force that acts contrary to interest).