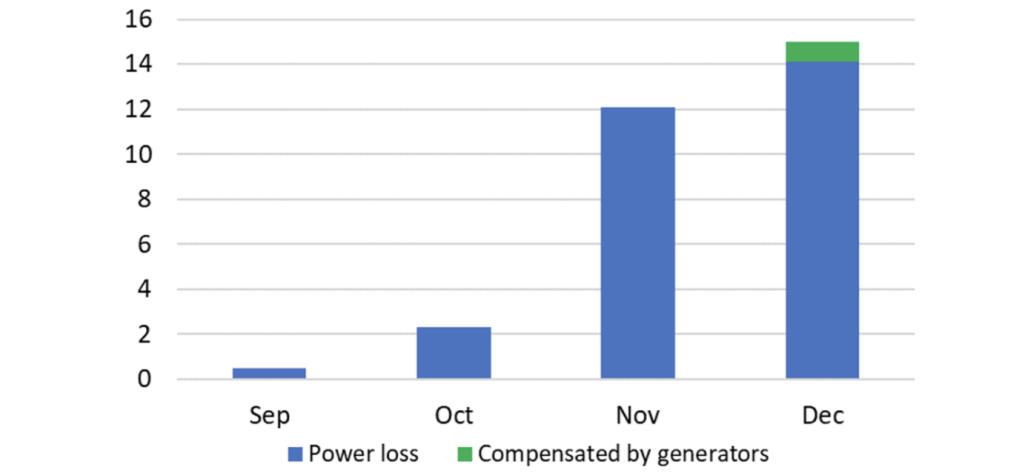

It’s just a year since the Russian invasion of Ukraine. I am not going to discuss the politics of this war in this post. There are plenty of sources for debate on this. Instead, I want to look at the economic consequences of the war for both Ukraine and Russia.

Let’s start with Ukraine. Back last year, an IMF staff report last March concluded that the country was paralysed. “With millions of Ukrainians fleeing their homes and many cities under bombardment, ordinary economic activity must, to a large extent, be suspended.” And over the last year, Ukraine has been destroyed by Russian bombing and arms. Thousands have died, millions have been displaced and/or fled the country. The economic base of the country is being annihilated.

Before the war, Ukraine was already a very poor country with a real GDP of just $160bn. Before this war is over, the physical loss from the war will match that GDP at the very least. The impact of the Russian invasion on the Ukrainian economy has been devastating. A third of enterprises immediately ceased operations, caused by the destruction of production facilities and infrastructure, the disruption to supply chains and dramatic increases in production costs.

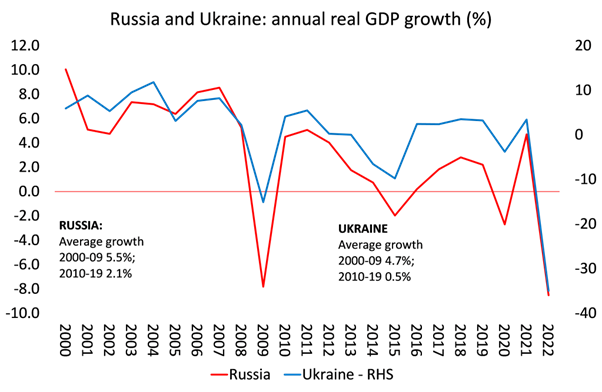

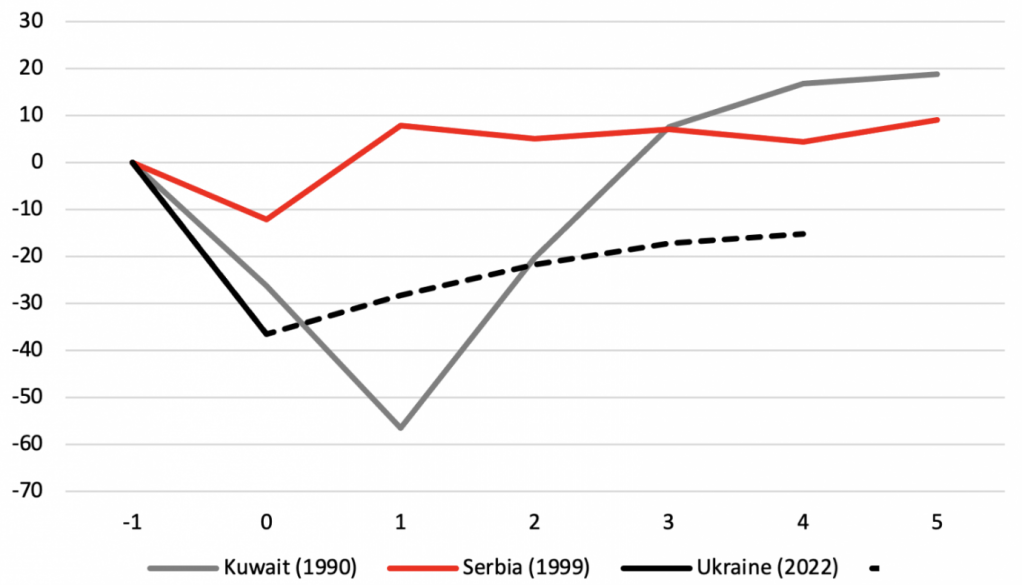

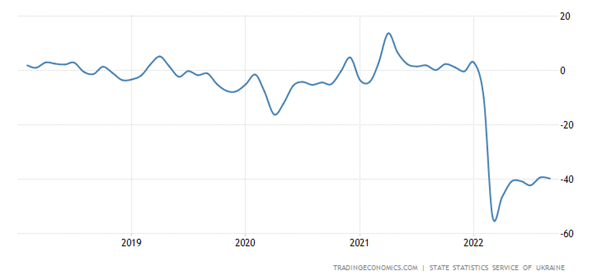

As a consequence, GDP fell 15% in 2022 Q1 and a staggering 37% in Q2. The loss has been greater than what happened to Serbia when NATO bombed the country into submission, but not yet as bad as the damage that Kuwait suffered from the Iraqi invasion and the subsequent US reprisals.

In Q3, GDP recovered a little to be down only 30.8% yoy. But the intense bombardment by Russia of Ukrainian energy infrastructure during Q4 has taken the rate of loss back further to 41% yoy, making an average fall in GDP for 2022 of about 32%.

Ukraine: real GDP growth (% yoy)

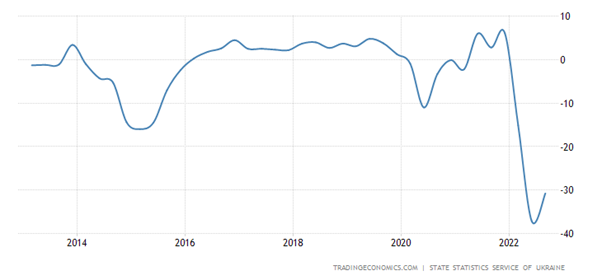

The near-daily aerial attacks on the country’s power grid and the frequent stalling in allowing ships to leave Ukrainian ports have hindered the economy.

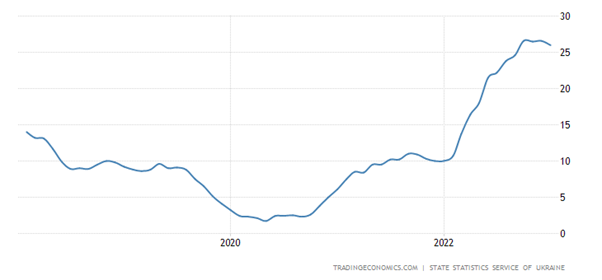

Length of power outages in October-December 2022 (% of productive time)

This includes a 39% plunge in private consumption, caused by supply shocks, depressed real disposable income and consumer confidence and by over six million refugees fleeing the country. Investment has collapsed to less than half of where it was in 2021, limited mostly to replacement of capital goods in areas of the country where that is still possible. Industrial production decreased by about 40% in the year.

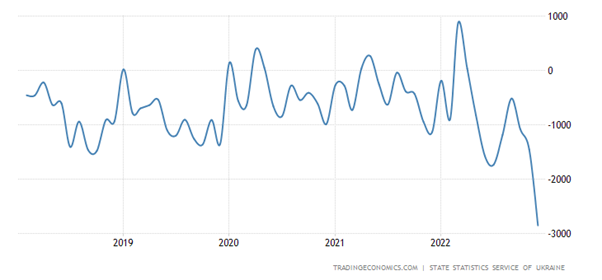

Ukraine: industrial output % yoy

With huge supply shortages in key necessities, inflation has jumped to about 27%.

Ukraine: inflation rate % yoy

And the trade deficit has nearly tripled from $4.4bn in 2021 to $11.2bn in 2022. Imports of key goods have fallen 24%, but exports have collapsed even more, by 49% compared to 2021.

Ukraine: monthly trade balance $bn

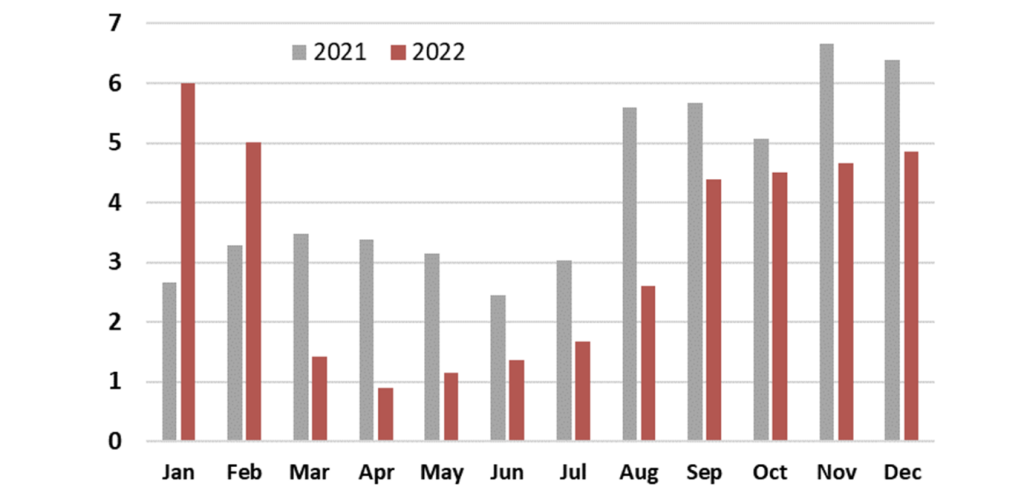

Prior to the war, 89% of Ukraine’s grain exports were transported via Black Sea ports. The Ukrainian ports of Odesa, Chernomorsk, Pivdennyi and Mykolayiv were handling up to 6m tonnes of grain per month in 2021 and were preparing to set new records in 2022 thanks to investment in expanded port infrastructure and bountiful crops. In the war grain exports collapsed. A partial reopening of Ukraine’s seaports in August after a brokered agreement with Russia allowed monthly grain exports to reach over 4m tonnes. However, frequent stalling by Russia in allowing ships through the blockade, elevated insurance and freight prices and recent threats to halt the grain corridor altogether have meant that November and December exports have again fallen back relative to 2021 export volumes.

Ukraine grain exports m tonnes

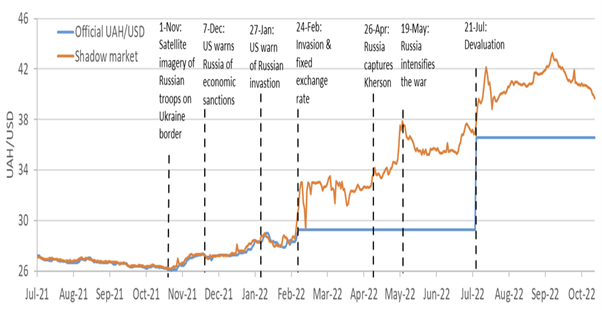

The collapse of trade meant a desperate shortage of hard currency like dollars. The attempt of Ukraine’s central bank (NBU) to fix the hryvnia to the dollar could not be sustained. So last summer, the currency was devalued sharply. Even so, the new fix was not sustainable and the gap between the official and shadow exchange rates continued to widen. That means inflation will continue to rise.

UAH/USD exchange rates (official and shadow)

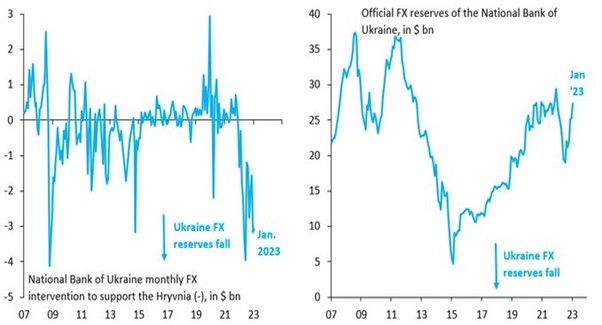

In trying to defend the fixed exchange rate, the NBU’s net stock of reserves fell almost 40%. Many better-off Ukrainians fled the country taking their cash with them. Cash removed from the banks increased by almost $9 billion in January-September 2022. While this was partially covered by remittances from refugees and military and humanitarian aid from the West, Ukraine lost around $6 billion overall in international reserves.

Ukraine: official FX reserves $bn

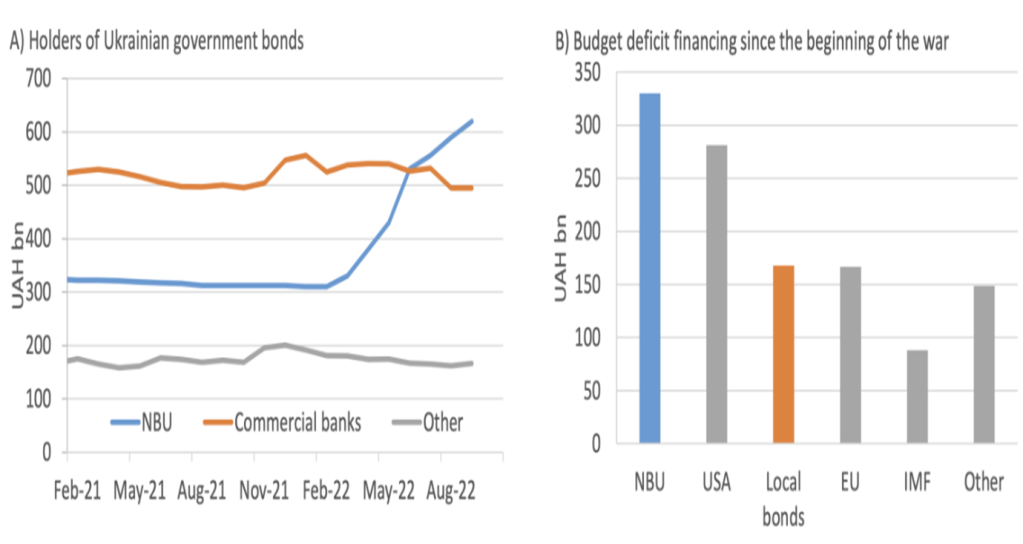

Despite foreign cash support, there is still not enough to fund the war effort and maintain some semblance of public services. So increasingly the government budget deficit, which widened from 3.6% of GDP in 2021 to 42% in 2022, has been financed by the ‘printing’ of money. To fund the deficit, the government issued bonds and called on the NBU to buy them. The NBU is now the largest holder of Ukrainian government bonds. With production falling and money supply rising, this is a recipe for further acceleration in inflation for the purchase of necessities.

Ukraine: budget deficit financing UAH bn

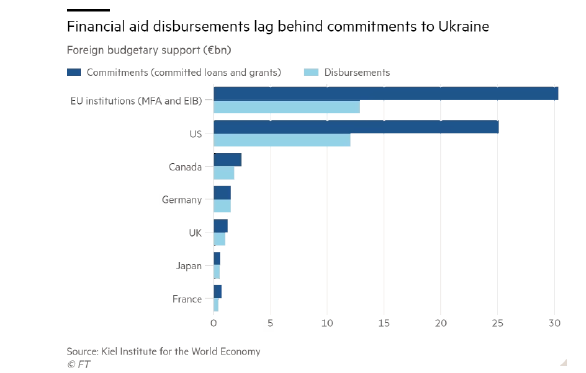

The bottom line is that without foreign aid, both military and financial, Ukraine could not have continued its military operations, support basic services or meet its external obligations. Ukraine’s finance ministry had received €31bn by December 2022 of the €64bn promised by western countries after Russia launched its full-scale attack last February, research by the Kiel Institute for the World Economy has found.

That’s about 75% of the pre-war stock of international reserves. The US and EU have now jointly agreed to support Ukraine with $3bn per month in 2023, or another $36bn in 2023.

In addition, Ukraine is looking for IMF-World Bank funding. It wants a full three-year programme of $15-20 billion, which it is likely to get. But that loan hinges on a range of conditions, including endorsement from the G7 nations and Ukraine’s other donors and creditors ensuring the sustainability of the country’s debt. The plan would also require unprecedented changes to IMF lending rules so the fund could lend to the war-torn country – Ukraine would thus get special support not available to other poor countries.

But Ukraine would still have to agree to ‘structural reforms’ and that usually means fiscal austerity, tight monetary policy (ie high interest rates), privatisation and the deregulation of the economy, including floating the currency. In other words, the classic neo-liberal IMF programme imposed on a debtor country – although in this case with willing support from the Ukraine government.

Ukraine needs roughly $45 billion in 2023 to keep its economy running. Undoubtedly, this is a large amount, but it is only 0.1% of the GDP of Ukraine’s allies, 4% of NATO’s annual budget. But that does not cover the cost of reconstruction after the war.

So far, estimates for the physical loss amount to about $130bn or near 70% of pre-war annual GDP. The World Bank estimates that Ukraine’s produced capital stock per capita in 2014 was approximately $25,000, which amounts to approximately $1.1 trillion at the aggregate level. Early reports by government officials and business leaders suggest that 30-50% of that capital stock has been destroyed or severely damaged. Assuming 40% destruction, that cost stands at $440 billion. In addition, on the assumption of a cost of €10,000 per refugee (per year), the cost of financing 5 million refugees for one year is €50bn, or 0.35% EU GDP.

Ukrainian sources estimate the cost of restoring infrastructure: financing the war effort (ammunition, weapons, etc.); losses of housing stock, commercial real estate, compensation for death and injury, resettlement costs, income support, etc.) and lost current and future income will reach $1trn, or six years of Ukraine’s previous annual GDP. That’s about 2.0% of EU GDP per year or 1.5% of G7 GDP for six years.

Who is going to pay? Don’t expect a fast post-war recovery as happened after WW2 with the US Marshall plan. By the end of this decade, even if reconstruction goes well and assuming that all the resources of pre-war Ukraine are restored (ie eastern Ukraine’s industry and minerals are in the hands of Russia), then the economy would still be 15% below its pre-war level. If not, recovery will be even longer.

Ukraine was already a country with an aging population and a dramatically falling birth rate. The war has deepened these problems, with five million women and children escaping to higher-income countries, where Ukrainians have been allowed to get local work permits. As the war drags on, many of these refugees will find jobs and decide to settle abroad.

The damage to those staying in Ukraine is immense. Learning losses by Ukrainian children are a particular worry: Ukraine will end up with lower quality additions to its workforce due to war-caused (and prior to that, Covid-caused) disruptions in the learning process. These losses are estimated to be in the order of $90 billion, or almost as much as the losses in physical capital to-date. Studies also show that a war during a person’s first five years of life is associated with about a 10% decline in mental health scores when they are in their 60s and 70s. It’s not just pure economy that’s the problem but also the long-term damage to those Ukrainians staying.

RUSSIA

Now let’s turn to the Russian economy. It’s not war damage to buildings and infrastructure that is hitting the Russian economy – although casualties in Russian troops has been huge – some 200,000, according to Western sources. Probably much less, but still high. The real hit to the economy is from economic sanctions by the Western powers. They have gradually taken their toll. The West, NATO and the EU did not respond to the invasion with armed intervention but resorted to economic sanctions – the new weapon of war. https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2022/02/27/russia-from-sanctions-to-slump/

Financial sanctions froze approximately half of Russia’s Central Bank (CBR) international reserves (which totalled $630 billion at the end of January 2022) and hindered Russia’s largest banks’ ability to transact in the most widely used foreign currencies. Several banks were also disconnected from the SWIFT messaging system. Russian entities, including banks, were restricted from carrying out investment or financing operations in most jurisdictions. Trade restrictions, in addition, limited the export of certain goods and technologies to Russia. Despite this, sanctions did not stop Russian energy revenues rocketing – at least up to now.

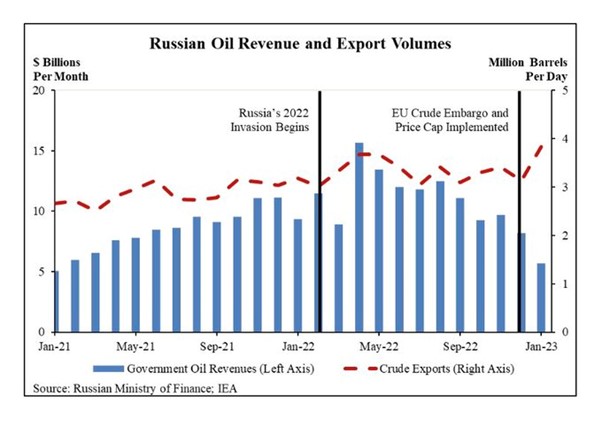

Russia: oil revenue and exports $bn

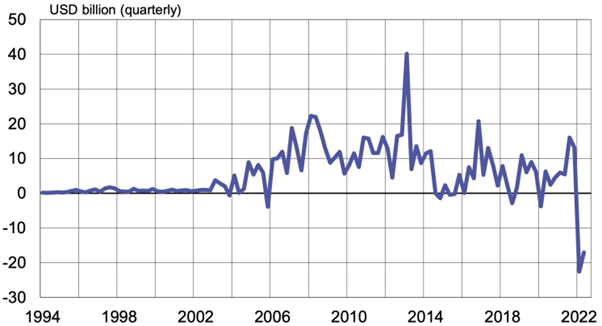

The combination of high hydrocarbon prices and import compression drove the Russian trade surplus to a record high. In the first half of 2022, Russia posted a cumulative surplus of $147 billion (15% of GDP), equivalent to approximately half of the Russian foreign exchange reserves that were frozen at the outburst of the war. Russia’s trade surplus eventually reached $370 bn in 2022 vs $190 bn in 2021. Two thirds of this $180 bn rise was from higher exports; one-third is from lower imports. It was this energy price windfall that’s paying for Russia’s current spring offensive in Ukraine.

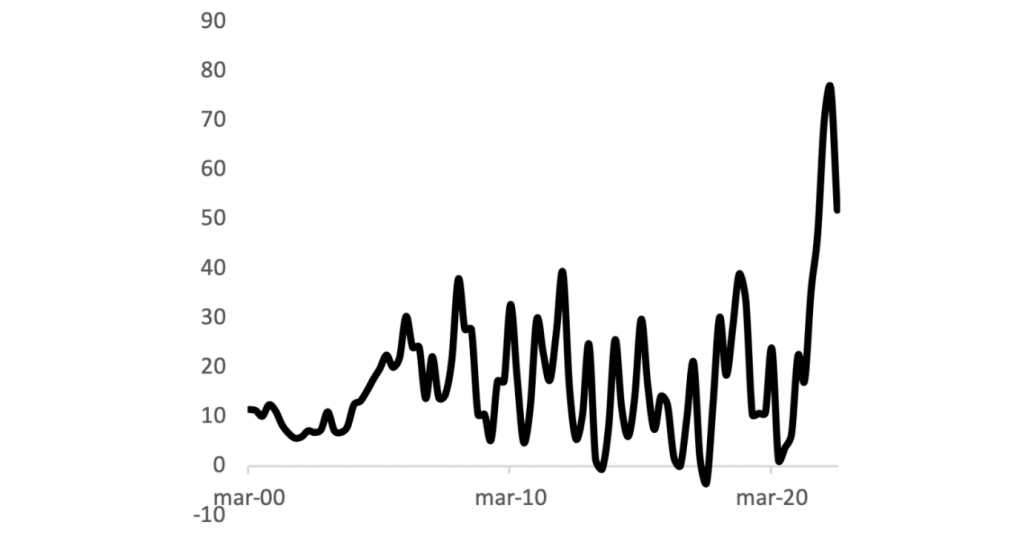

Russia: monthly current account $bn

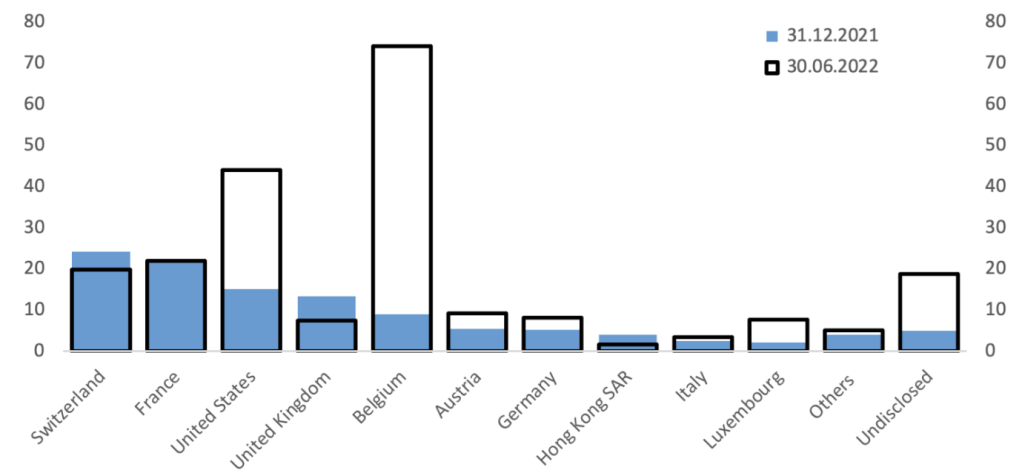

As a whole, the net external position of Russia’s private sector improved by nearly $170 billion. Cash left the country, mostly ending up in the Eurozone!

Cross-border banking liabilities to Russia (stock, US billion)

These assets represent funds from securities held in custody on behalf of sanctioned Russian residents which could not be (and were not) transferred back to Russia. These funds piled up on Euroclear’s balance sheet as deposits. There was also a surge in the stock of Russian deposits from nearly $5 billion to close to $20 billion, most likely related to increased trade with non-sanctioning countries like China.

Nevertheless, the overall economy has not escaped contraction in 2022. Russia’s economy contracted 2.1% in 2022, less than expected. But looking ahead, GDP is expected to fall by 2.4% year-on-year in the first three months of 2023, according to the Central Bank of Russia.

Russia: real GDP growth % yoy

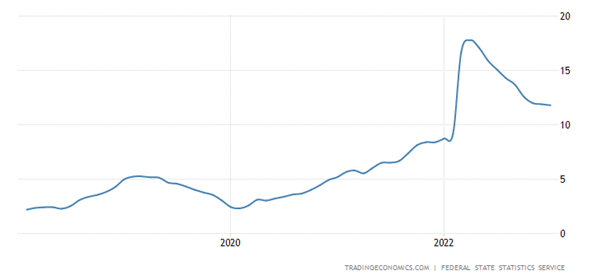

Inflation rose sharply during the year to a 17.5% yoy peak before subsiding a little.

Russia: inflation rate % yoy

In contrast to Ukraine, Russia’s large current account surplus has undoubtedly contributed to sustaining the ruble. However, it also stems from the fall in imports due to the war and related sanctions. That means fewer goods for Russian citizens and a lack of components for the war effort and domestic production (e.g. car production fell around 77% year-on-year in September).

While Ukraine is being bolstered by massive foreign aid, Russia is struggling to find foreign backing. Russia’s net foreign direct investment inflows have dropped into negative territory. Hundreds of foreign companies have decided to leave Russia.

Russia: net foreign capital flows $bn quarterly

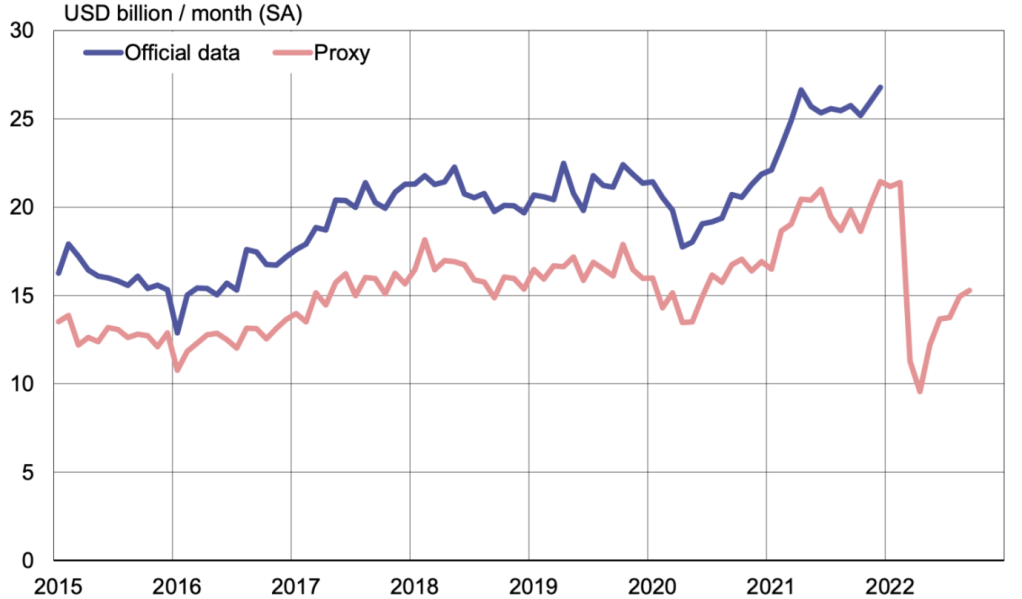

Imports of many technology products have fallen particularly sharply. Russian goods imports in September were down by 28% from pre-invasion levels, according to some estimates.

Russia: import levels $bn

Defence spending now accounts for a third of all budget spending approved for 2023. The war is rapidly reducing the most able-bodied part of the workforce and emigration has increased. There are about 30m men of fighting age in Russia, but only 9-10m have military experience, primarily due to conscription. And that figure includes those who may be sick or disabled or who have exemptions from service, for example due to their profession. Russian demographers also agree that about 500,000 Russians have fled the country on an at least somewhat permanent basis since the start of the invasion, a majority of them men of fighting age.

Russia has a large stock of financial assets ‘for a rainy day’. And it is raining. These assets are controlled by Russia’s National Wealth Fund (NWF), which have grown from 1.9% of GDP in 2008 to 10.2% by the beginning of the invasion. But in one year, it is down to 7.2% of GDP — due to currency revaluation and the state using these assets to cover its budget deficit. In 2023, the budget law projects a deficit of Rbs2.9tn, equivalent to 1.9% of GDP, much of which the state plans to cover with NWF money.

The problem Russia has is its economy is really a one-trick pony, almost totally founded on energy and resources production and exports with relatively poor, low productivity manufacturing output. And that sector is highly dependent on imported high-technology goods and inputs. With sanctions now limiting the availability of technology and financing, Russia’s prospects for import substitution of technological products have become even more limited. While Russian imports from China and Turkey have exceeded pre-war levels in recent months, the share of technology products has remained unchanged.

As a result, Russia’s medium- and high-technology industries have contracted sharply. The production of trucks is down by 40%, TV receivers by 44% and excavators by 69%. Russian wood and steel producers have been unable to find alternative export markets that offer profitable price levels. In these industries, output has declined sharply and companies have suffered heavy losses.

Of course, the energy sectors have remained robust, so far. Oil and gas output has not fallen. Moreover, the spike in global oil prices has supported Russia’s oil revenues (even if Russian oil has been sold at a discount) together with a reorientation of Russian oil to new export markets, most notably India and China.

But things could change in 2023. Europe has managed to get through the winter without Russian energy by importing expensive liquid natural gas from the US and by reducing consumption, given relatively warm weather. EU restrictions on oil imports entered into force in December 2022. And price caps on Russian oil and gas exports started at the beginning of this month.

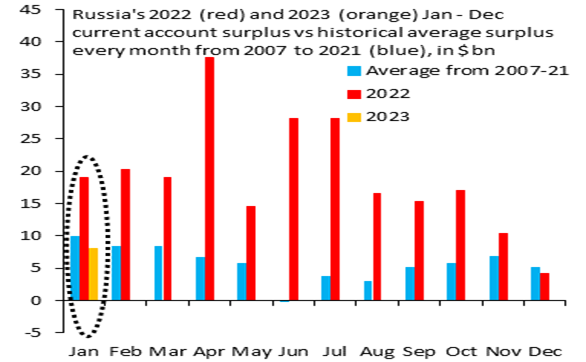

This will reduce Russian revenues over this year. It already seems to be happening. After the huge current account surpluses in 2022 (red), the Jan 2023 surplus (orange) was below its historical average for Jan (blue).

If these EU measures bite and reduce Russian energy production and exports, then Russia will experience a significant slump this year, perhaps a contraction of 7–8%, a decline similar to that seen in 1998 and 2008.

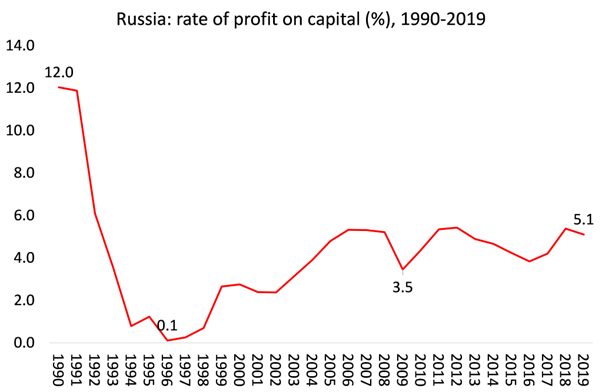

As I have shown in previous posts, Russia’s economy was already slowing before the pandemic slump and of course during the slump. Potential average growth is probably no more than 1.5% per year as Russian growth is restricted by an ageing and shrinking population, with low investment and productivity rates. The profitability of Russian productive capital even before the war was very low.

Investment is hampered by falling profits and severely restricted access to foreign financing. Increasing emphasis on military industries and a lack of access to Western technology will weigh further on productivity of key industries.

Russia’s long-term growth estimate has been cut substantially in the IMF World Economic Outlook forecasts. Russia’s economy is on track to be at least 8% smaller by 2026 than it would have had Putin not ordered the attack on Ukraine.

WHAT NOW?

In summary, Russia cannot rely on foreign financing to fund the war. But it can continue its invasion in the face of economic sanctions from the West, as long as its energy revenues do not fall too much and its FX reserves are not depleted too much; or its domestic economy does not contract so much that Russia’s citizens really cannot face any more. That could be years.

In contrast, with a much smaller economy, Ukraine is already destroyed domestically and does not have enough domestic or export revenues to fight this war; so it must rely on foreign funding. As long as that comes in sufficient amounts, it too can continue for years.

Both Ukraine and Russia are now war economies. By that I mean the state now controls the direction of the economy ie where production and investment are employed. The ‘free market’ is replaced by state control for the military effort.

But there is a difference between the two economies that will be expressed after the war ends – if it ever does. Post-war Ukraine, if the current government survives, is committed to a neo-liberal free market economy relying on foreign investment and companies taking over the main resources and being integrated into the EU. The model to follow will be that of Poland and Baltic states ie no welfare state to speak of; pensions reduced; no trade unions and labour rights; deregulation of markets; and ultimate reliance on capital transfers from the West.

In contrast, post-war Russia, assuming Putin or his cronies are still in power, will opt for a much more state-directed economy than before. Freewheeling oligarchs doing their own thing will not be tolerated (only Putin’s cronies) and key resources and investments will be closely controlled by the state.

Before the war, there was one thing in common for both countries: a high level of corruption between billionaires and politicians. That is unlikely to change, as recent revelations of corruption in the government of Ukraine have revealed. And don’t expect the EU to cleanse ‘free market’ Ukraine; after all, most of Eastern Europe’s states are riddled with corruption with little sanction and it seems that even EU parliament members are also engaged. As Bernie Sanders said recently: “Yes, Russia has oligarchs, but so does the US.” – and indeed everywhere.

Russia has lost 200k soldiers.

Dream on….

Like they run out of weapons, like they losing, like Putin is dead….

Cloud cuckoo land

These data are as real as $ 3.00 notes, to make any forecast about them is to say anything, just for the losses in the Russian War, 200,000 soldiers, is a joke, the most sinister estimates are around 50,000 (dead and serious injured).

Taking data from western sources is a fantasy.

Will “assuming Putin or his cronies are still in power” Will not Sunack and his cronies or Biden and your son

“I am not going to discuss the politics of this war in this post.” ???

The restrictions on Russian access to high-technology inputs seems like a massive deal. It would be good to know more about that. Just how extensive is it, and how significant?

I think the answer might be very few because currently, the majority of Russia’s weapons were designed in the 1990s to early 2000s, such as Kh-101, Kh-55, or 3OF39. Thanks to the development of technology, today, in 2023, even a 600$ personal computer has a much more powerful CPU than the F-22’s that produced in 2005. Moreover, due to consumerism, anyone could buy pounds of obsolete but still usable chips as electronic waste at nearly no cost. No one would use Pentium CPUs at all, but they are quiet enough for weapons.

Stating a mild decrease of Russia’s GDP in 2022 and also saying that the production of trucks was -40% smaller than in 2021 is a joke

What’s the problem with this one? Both facts are true unlike some other mentioned in other comments (200k dead).

Ukraine is in an even worse situation than the data tell us because they’re still considering the eastern oblasts (Donetsk, Lughansk, Zaporozhie and Kherson) and Crimea as their own territory, i.e. that Ukraine still enjoys its territorial integrity.

Fact is Ukraine as we knew it has already ceased to exist. In the literal sense.

Russia’s economic performance is still well into the territory of a nation engaged in a direct war (i.e. no proxy war). Wars are inherently destructive to any empire, kingdom, nation-state etc. etc. economy, and -10% and even more falls in GDP, as well as sharp rises in inflation are normal.

The concept of a lucrative war — that is, that because a nation-state is waging a war, its inflation will lower and its GDP will grow — is a historic innovation of the USA (since the Vietnam War) and, so far, it was never replicated. It is a historical anomaly that other nations cannot replicate and will probably never be replicated. Not even the Roman Empire at its apex had such privilege/ability (that was the main reason it eventually declined and fell).

As for the corruption thing, I miraculously agree with Varoufakis on this one: there really isn’t a significant ontological difference between corruption and business as usual in capitalism, but one of vulgarity of method. The “northern Europeans” are as corrupt as the “southern Europeans” the difference being that the northerners use a more “high-tech”, more “sophisticated” method of robbing. A white collar crime is less brutal, but often orders of magnitude more devastating than a “street crime”.

So, Russia’s vaunted stratospheric corruption may be just a Western fabrication, akin to the ancient Romans telling stories about the barbarians drinking wine from their enemies’s skulls. For example, is Russia objectively (in monetary terms) more corrupt than, say Brazil? And yet, nobody keep telling us about the imminent collapse of Brazil, which is a Western darling, the poster model of the good servant.

“The problem Russia has is its economy is really a one-trick pony, almost totally founded on energy and resources production and exports with relatively poor, low productivity manufacturing output. And that sector is highly dependent on imported high-technology goods and inputs.” Michael your words. So alongside the accepted definition of an imperialist country: it must dominate technologically, must be an exporter of capital and must be the net recipient of surplus value, it must also be a one-trick pony.

On the casualties. In March last year, Israel warned Zelensky not to go to war with Russia having seen the abilities of the Russian army in Syria. It was one of the reasons Zelensky entered into negotiations at the time only to be stymied by the US and UK (recall Johnson’s visit to Kyiv). Well during the height of the debate on tanks, it appears the Israeli’s wanted to bring some reality into the discussion to stop the continuous escalations and crossing of red lines. They issued their casualty figures on the 5th Feb via a Turkish newspaper and subsequently have not admitted to nor denied the figures. According to Mossad, the Israeli intelligence agency, 157,000 Ukrainian soldiers, 2,458 foreign fighters, 5,360 “mercenaries,” and 234 “NATO military trainers” from the United States and United Kingdom have died in Ukraine since the start of the 2022 war. In contrast, only 18,480 Russian soldiers are believed to have been killed in the same period. No, Mossad wasn’t itself counting corpses. These were the best estimates prepared by others counting casualties using official sources, social media, newly dug graves, newspaper obituaries etc. which were available before the Mossad report. In addition the Ukrainian figures do not include the approximate 35,000 soldiers missing in action. While it is true that Russian casualties are relatively higher in February, the continued 6 to 1 advantage in Russian artillery, particularly their dreaded flame-thrower missiles, continues to kill more Ukrainians than are lost on the Russian side.

This all looks like a nasty stalemate, for the Ukrainian people the worst; for the Russian people next. This is an inter-capitalist war, which is destroying capital, but also making profits for some. These figures show the stalemate will go on unless one side or the other falters. Certainly Ukraine is at the biggest disadvantage due to this criminal invasion. The goal of ‘total’ victory is a bloody and anti-working class will-o-wisp. Only working-class uprisings against both ruling classes, and unity between both country’s labor movements, would ‘solve’ the capitalist issue. But ‘real-politik’ will demand an eventual division of territory and ‘peace.’

Sad that former soviet republics have to fight due to NATO/EU

Thanks for this excellent analysis. Posted to Center on Capital & Social Equity – http://www.inequalityink.org.

I am sorry, Mr Roberts, that this blog has attracted an unusually large number of people unable to express themselves clearly – while still disagreeing with more or less everything that you said. The exception is vk who, in his or her usual prolix fashion, manages actually to convey two points, and to my surprise I agree with him:

a) Russia will be in a better situation economically than Ukraine when fighting stops – I think you were saying much the same thing; and

b) both countries are severely corrupt, and there may be be a parallel with Western countries and their businesses and related government activity. Here, however, I think the Western problem is more the deception of the people as to where their interests lie, rather than financial corruption – though there is more than enough of that, even before the faiure to curb tax havens is added in.

Thank you for trying to pull together some halfway usable figures.

Sorry: “failure” in the penultimate line, not “faiure”. (And my apologies for any other literals which have escaped my failing eyesight.)

Garbage in garbage out… that is how I would summarize your analysis. Two statements you made , “200,00 russian loses” bullshit… western and Ukrainian propaganda… and two “Russia a one trick pony”… Russian is probably the only self sufficient county in the world today., additionally With your western mindset stuck in the ahistorical narrative created by the west… that Russia invaded Ukraine.. (when the west provoked and planned over several years to induce a Russian response to the western sponsorship of the genocide of the Ethnic Russians in the Dobass),, lead me to discount your analysis as a whole , even though there may be valuable information.

Dear Danna You could be right that 200,000 Russian casualties is wrong. Ok. No country is self-sufficient in global capitalism and Russia lacks technology and a strong manufacturing base. But its energy and resources exports are an important support for the economy; but they are under threat. It is a fact that Russia invaded Ukraine – but I agree entirely that this was provoked by NATO and Ukrainian nationalist action. If you read all my posts on Ukraine and Russia, you will see I do not agree with the West’s version. That’s my garbage.

Thanks Michael for your excellent in-depth analysis of the economic situation in Ukraine.

Unfortunately, your analysis of the Russia economy left much more to be desired.

Apart from the ludicrous propaganda figure of 200,000 Russian dead – even the BBC estimates it ten times less than that at around 20,000 – I too found your assessment of the Russian economy as a one-trick pony to be very unsatisfactory. Russia is not just dependent on energy but is also strong in a wide range of other products including food, key metals, rare gases, minerals, and so on. Surely, the big negative effects of the banning of imports from Russia to Europe and North America has brought home the strength of the Russian economy.

Where I found Michael’s assessment of Russia’s economy to be most deficient was in its failure to address Russia’s ongoing pivot away from Europe and towards Asia. Given that the Asian economies are booming compared to the declining western economies, this pivot is likely to yield much better results for Russia in the future than its past orientation towards Europe and the Western economies.

In particular, China and Russia have committed to integrating their economies which has already led to a massive increase in trade up by 30.9% in 2001, and by 30% in 2002 (now at $190 billion). Such trade is rapidly replacing the gaps in technology that have opened up because of the western sanctions. For example, Chinese cars are now rolling off Russian production lines in large numbers. If China and Russia really do take serious steps to integrate their economies with joint operations between their state industries etc. then Russia has a great chance to tap into China’s success and develop its manufacturing sector, update its infrastructure and so on.

The same is true of Russia relationships with other Eurasian states. For example, Russia is in the process of greatly increasing its trade with Turkey, Iran and India, and creating special transport corridors to facilitate this.

Thus, by hitching its wagon to the fastest growing economies in the world (China, India etc.) Russia’s medium and long-term economic prospects could be relatively healthy.

I`m extremely reticent to come with any judgements as to the facts of the war, although I think the idea of the Russians having lost 200,000 is unsustainable – it would seem to be contradicted by the military strategy adopted by Russia which is one of strategic retreat when necessary and the use of overwhelming artillery to blast Ukrainian positions. As I understand, there has been some collation of figures from funeral notices in Russian newspapers and other sources and an estimate of 14,500 has been arrived at, as to the overall total of dead up until the the beginning of February this year. Conversely, the Ukrainian losses would seem to be extremely high – in the hundreds of thousands which is linked to the political decision, in opposition to the Ukrainian military leadership, of refusing to countenance a retreat from such places as Bakhmut.

Well summarised Stephen. Most injuries on the Ukrainian side appear to be from artillery fire. A common complaint of the Ukrainian soldiers is that they rarely see Russian soldiers because they are sheltered a long distance away behind the artillery.