Isabelle Weber is an assistant professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and the author of How China Escaped Shock Therapy. She recently wrote in the UK Guardian newspaper that price controls should be considered to deal with the inflation spike hitting many economies in the wake of the COVID crisis.

Weber’s piece was just 800 words long, but it provoked a squall of debate between radical post-Keynesian economists and more orthodox Keynesians over the effectiveness of price controls to control rising inflation of prices in general and to deal with the current inflation spike in the major economies.

Weber is author of the highly acclaimed book on the zigs and zags in the economic policy of the Communist leaders in China during the period of the country’s unprecedented economic rise. My review of her book can be found here. Weber comes from one of the more radical departments of economics in the US and is apparently a big fan of post-Keynesian authors like Minsky and Kalecki (but not it seems Marx). She also is a supporter of Modern Monetary Theory.

Inflation rates have been rising in most of the major economies to levels not seen since the 1970s. Some mainstream economists have been arguing this spike in inflation is due to excessive demand by consumers who have huge piles of money given to them by governments during COVID (ie ‘quantitative easing’) and by fiscal stimulus programmes designed to spark an economic recovery. Much of these measures have been financed increasingly by central bank credit injections, MMT style. The mainstream view is that it is time to rein in these monetary injections with interest rate hikes and by tapering off quantitative easing. Post-Keynesians and MMT promoters oppose this and want to continue with fiscal boosts and monetary easing. So Weber offers an alternative policy to tighter monetary measures and fiscal austerity (ie more taxes and less spending to control rising inflation). It is price controls.

In her piece, Weber likens the current inflation spiral to just after WW2. Then even mainstream economists advocated price controls. Weber argues that: “Price controls would buy time to deal with bottlenecks that will continue as long as the pandemic prevails.” She quotes the much-revered post-war Keynesian economist JK Galbraith: He explained that “the role of price controls” would be “strategic”. “No more than the economist ever supposed will it stop inflation,” he added. “But it both establishes the base and gains the time for the measures that do.” So just a short-term measure then. But Weber then adds that “Strategic price controls could also contribute to the monetary stability needed to mobilize public investments towards economic resilience, climate change mitigation and carbon-neutrality.” In other words, not a short-term measure after all, but a key policy that would control inflation indefinitely so that public investment financed by central banks a la MMT does not have to be curtailed.

Mainstream economists erupted nastily to Weber’s argument. Orthodox Keynesian guru Paul Krugman was particularly scathing. That’s because it is a law of neoclassical economics that governments cannot buck markets and if controls on market prices are imposed by government, that will lead to significant imbalances of ‘supply and demand’ ie either shortages of supply and even outright recession. Let the market rule prices because you cannot stop the sun rising in the east, or if you do, there will be permanent darkness.

On one level this dispute is misleading. That’s because in many sectors of capitalist economies, price controls are already in operation. There are rent controls; transport fare price increase caps, and price caps on utilities like gas, water and electricity in many countries. Price regulation on private ‘monopolies’ and state industries can be found everywhere.

But this is not what Weber means by ‘strategic price controls’. Instead, price controls are offered as a policy alternative to control inflation compared to monetary tightening and fiscal austerity as the mainstream advocates. But price controls to control rising or high inflation in capitalist economies will not work precisely because inflation is determined by the laws of motion in a capitalist economy that are more powerful than controls. Sure, price controls on drugs or transport fares can play a role for specific sectors where perhaps just a few companies dominate the price, but because such controls just cover a sector and not a whole economy, they won’t be effective overall. Targeted price controls may not distort overall supply and demand movements in an economy but for that reason, they have little effect on overall inflation of prices, which is being driven by other factors.

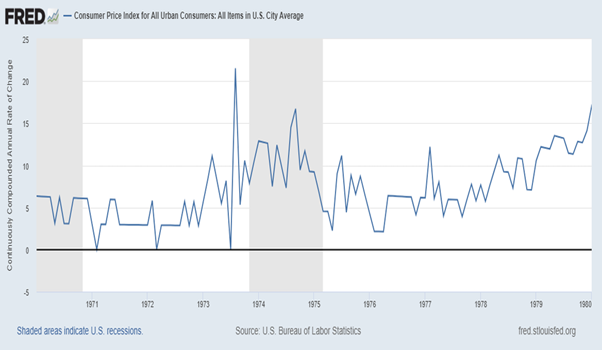

The historical evidence of overall price controls in a capitalist economy is that they either work at the expense of production by creating shortages or even provoking a recession. Take the 1971-4 price controls introduced under the Nixon presidency in the US. It is argued that they worked to control price rises for a while, but as soon as they were lifted in 1974, price inflation rose again. A paper by Blinder and Newton concluded that “According to the estimates, by February 1974 controls had lowered the non-food non-energy price level by 3-4 percent. After that point, and especially after controls ended in April 1974, a period of rapid ‘catch up’ inflation eroded the gains that had been achieved, leaving the price level from zero to 2 percent below what it would have been in the absence of controls. The dismantling of controls can thus account for most of the burst of ‘double digit’ inflation in non-food and non-energy prices during 1974.” Actually, during the period of price controls, inflation started to accelerate in 1973 as the US economy reached a peak of expansion alongside falling profitability and slowing investment growth. What lowered inflation in the end was the deep recession of 1974-5, not price controls.

Recently economists at the White House Council of Economic Advisors issued a paper suggesting that price controls could work just as they did after WW2. The White House economists reckon that “the inflationary period after World War II is likely a better comparison for the current economic situation than the 1970s and suggests that inflation could quickly decline once supply chains are fully online and pent-up demand levels off.” Yes, but exactly, if the ‘sugar rush’ of pent-up consumer demand falls back and supply bottlenecks are resolved, then inflation rates will probably subside. So how would price controls help at all?

Like the White House, Weber says controls could be used in the short-term to get a ‘breathing space’ on inflation; but she is really advocating controls as a necessary long-term policy alternative to fiscal and monetary restraint, which is not the same. That price controls are seen as a long-term, even permanent, policy by Weber and the post-Keynesians is revealed by the other big bugbear of post-Keynesianism after fiscal ‘austerity’, namely monopolies.

As Weber says, “a critical factor that is driving up prices remains largely overlooked: an explosion in profits. In 2021, US non-financial profit margins have reached levels not seen since the aftermath of the second world war. This is no coincidence…. Now large corporations with market power have used supply problems as an opportunity to increase prices and scoop windfall profits.” So, you see, rising inflation is the result of ‘price gouging’ by monopolies. We need price controls on monopoly pricing power.

But it’s just not true that rising profits (margins) lead to inflation. As a study by Joseph Politano finds : “The rise in corporate profits is largely attributable to this increase in spending: money first went from the government to households in aggregate, and now those households are spending money and sending it to corporations in aggregate. The jump in aggregate corporate profits is no more responsible for the rise in inflation than the prior jump in household income.” Politano adds: “there is no causal analysis here. One could just as easily repeat this exercise by ascribing all inflation to the increase in income caused by the stimulus checks, because without good causal inference the whole thing is just conjecture about what “actually” caused inflation”.

Indeed, we could also claim, as mainstream economists do, that wage rises cause rising inflation because companies have to raise prices to sustain profitability. But there is no causal or empirical validity for this. A dose of Marxist theory on inflation shows that prices are fundamentally set by the value of labour time going into commodities on average and not by the components of that value in profits and wages. If wages rise, then profits fall and vice versa, at least on average, not prices. And the major capitalist economies are not dominated by ‘monopolies’ that can jack up prices as they wish. If that were the case, inflation rates would be continually rising, whereas from the 1990s to pre-pandemic 2019, inflation rates in the major economies were falling!

Monopoly capital is a term that does not really describe modern capitalist economies, just as ‘competitive capital’ did not really describe 19th century capitalism. Most sectors in capitalist economies have a small group of ‘oligopolies’ and a large group of small companies. Depending on the various weights of these two groups, prices will be driven by ‘regulating capitals’ (see Shaikh Chapter 7), which are usually in fierce competition with each other, within countries and internationally. Monopoly profits are not the cause of movements in overall inflation rates; only in some sectors where ‘natural’ monopolies exist and even there, competition and technical change can undermine monopoly control of prices over time.

The White House and Weber argument that price controls during and just after WW2 worked is really misleading. Then governments were in full control of the major sectors of the economy in order to direct them to the war effort. A war economy with the major companies and financial institutions working to a plan is nothing like the free-for all for the capitalist sector in profits and investment as in the current pandemic. Total price control in an economy would require total control by the state of the oligopolies over investment and production. And total control would only be possible by taking the oligopolies into public ownership with a plan for investment and production.

So when Weber (and it seems MMT-guru Stephanie Kelton) cite the example of successful price controls in Communist China in its early years, they are comparing apples with pears. Price controls won’t work to get inflation down without causing a recession in an economy dominated by the capitalist mode of production. Squeezing profits across the board by such measures will only lead to lower investment and production growth.

Weber ended her article with this: “We need a systematic consideration of strategic price controls as a tool in the broader policy response to the enormous macroeconomic challenges instead of pretending there is no alternative beyond wait-and-see or austerity.” Weber and Kelton and other post-Keynesians are raising price controls as an alternative to ‘austerity’ as advocated by the mainstream. And they are right to worry that ‘austerity’ is coming back. See this piece by Chicago economist, John Cochrane that blames inflation on excessive government spending.

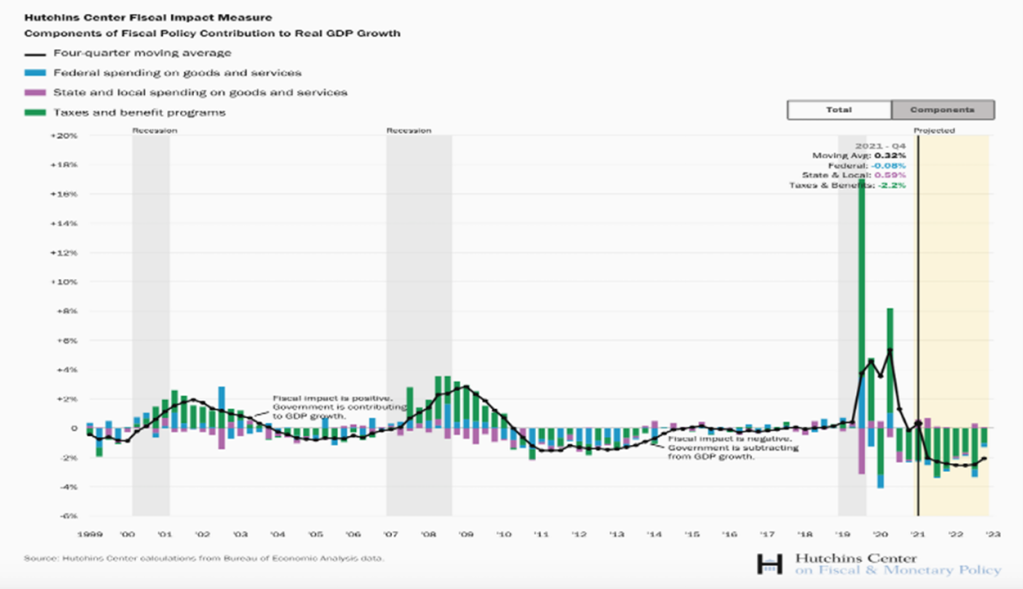

Already even under ‘profligate’ Biden, the government is set to take more out of the economy than it is injecting into it. According to the Congressional Budget Office, federal government spending is set to decline by 7% on average up to 2026 compared with 2021 levels while tax revenues are expected to rise by 25%. The US federal budget deficit will be halved in 2022 and kept down for the following years. So no Keynesian-style fiscal stimulus is planned – on the contrary. The graph below shows that US fiscal policy is no longer stimulating aggregate demand.

In my view, price controls cannot be an alternative policy to fiscal austerity in controlling inflation when the causes of inflation lie in the laws of motion of capitalist accumulation ie. changes in profitability, investment and output, not in monopoly power or monetary injections? In my view, the current high inflation rates are likely to be ‘transitory’ because during 2022 growth in output, investment and productivity will probably start to drop back to ‘long depression’ rates. That will mean that inflation will also subside, although still be higher than pre-pandemic. Price controls will be ignored.

Dear Michael,

I would like to ask some questions and comment on the paragraph below:

”

Monopoly capital is a term that does not really describe modern capitalist economies, just as ‘competitive capital’ did not really describe 19th century capitalism. Most sectors in capitalist economies have a small group of ‘oligopolies’ and a large group of small companies. Depending on the various weights of these two groups, prices will be driven by ‘regulating capitals’ (see Shaikh Chapter 7), which are usually in fierce competition with each other, within countries and internationally. Monopoly profits are not the cause of movements in overall inflation rates; only in some sectors where ‘natural’ monopolies exist and even there, competition and technical change can undermine monopoly control of prices over time.

”

1. How do you conceptualize an economy “sector”?

According to the third volume of Capital, I understand that the notion given to a “sector” is that of capitals competing mainly in term of productivity, trying to produce the SAME commodity at a price below its price of production.

Instead, the “sectors” Shaikh and you refer to, comprising of a few oligopolies and a “large-group” of smaller companies, do not produce the same commodity.

Usually, the “bunch” of companies are actually the producers and suppliers of the few oligopolies that do not really produce anything…

2. Accordingly, how do you conceptualize the “regulating” capital?

Again, from what I understand from Marx, the “regulating” capital is the one that produces a SPECIFIC commodity with the best available technique. If there are no obstacles, natural, legal or cost related, to using the best technique, then the regulating capital is also the most productive one, and it can produce at a price below the price of production, and thus capture a temporary super profit. This profit is temporary because, without any obstacles, the competitors will sooner or later catch up, and the price of production will be lowered.

Does this picture fit today’s reality?

3. How do you conceptualize the “monopoly/oligopoly”?

According to Lenin, Mantel, traditional soviet literature etc, it refers to a capital that can reap systematic super profits based on its market power. This market power usually is due to some property that creates a natural, or technological advantage that cannot be imitated by competitors.

Whether it is 1 only capital, or a few of them, is of lesser importance.

More importantly, the advantage might relate to the production of a given commodity, reducing thus the price of production (in which case mind that the monopoly capital would NOT be the regulating capital), or…

…it might mean that the given capital produces a commodity that cannot be produced at all, or at the same quality, or in the end of the day, demand, by other capitals…

In case of very complex commodities such as cars, mobile phones, laptops etc, hardly any two commodities can be really compared only in terms of cost of production, and not in terms of quality.

Shaikh’s statistics mostly ignore this reality, averaging together industries that produce completely different commodities (some of which produce just intellectual property…) and have complicated, power relationships among them, unlike most of classical marxist political economy of the 20th century that was trying to theorize the actual historical reality of capitalism as it evolved.

4. Moreover, you refer to “fierce” national and international competition.

Your own theories on imperialism, to which I largely -but not fully- agree, demonstrate the nature of that competition, which is very much (political, military, generally social) power dependent.

In the end of the day, how many decades will we have to wait for the profit of Apple, Microsoft, Chevron etc approach the general profit rate? For how many consecutive years will those monopolies be the “regulating capitals” of their “sectors”?

Actually, my own question is kind of meaningless. It should be rephrased:

For how long should we wait for the capital ownership and power constellations that go under the names “Apple”, “Microsoft” etc to be reproduced via commodities (in a multitude of sectors) that will not be produced monopolistically?

The fact that some monopolies can also go bankrupt doesn’t cancel my question for the mere reason that “Apple” is not the name of a commodity that competes within a sector, but for a capital constellation that operates in a multitude of sectors, generally under monopolistic conditions. If it fails at some point, capital will move to other sectors probably still highly monopolized ones…

Interesting essay.

Now that inflation is beginning to reappear, MMTers are starting to feel uneasy.

Having had two decades of low inflation, MMTers were confident that inflation would not accompany increasing employment (i.e. Phillips Curve is dead).

So they are now proposing to resort to price controls.

Good point and perceptive. I have always maintained that effective MMT would be inflationary from the outset. Effective meaning it is thrown into circulation, that is spent by recipients. The confounding aspect currently is that supply chain disruptions can be interpreted as full capacity having been achieved.

Agreed, price controls are like putting a cap on a sponge full of water, it don’t stop the drips. In any case within three months as demand, production and prices subside, this will be a moot discussion.

“A dose of Marxist theory on inflation shows that prices are fundamentally set by the value of labour time going into commodities on average and not by the components of that value in profits and wages. If wages rise, then profits fall and vice versa, at least on average, not prices.”

Except, Michael in his economic manuscripts of 1864-65 (which Engels edited for Capital vol 3) Marx revises that determination:

<The result of the wage rise of 25% is thus as follows:

(I) for capital of an average social composition, the commodity's price of production remains unchanged;

(II) for capital of a lower composition the price of production rises, although not in the same ratio again not in the same ratio as profit has fallen

(III) for capital of a higher composition the price of production falls, though again not in the same ratio as profit.

[Marx's Economic Manuscript of 1864-`1865, page 310, ed by Fred Moseley, Haymarket 2017).

Now there are a host of problems with the manuscript, not the least of which is if a general rate of profit can even be shown to exist as something other than a mathematical abstraction, but still Marx does modify the "standard" position that wage changes aren't reflected in price (as opposed to value).

I would suggest the overall level of profit is unaltered despite the rearrangement of profits caused by changed patterns of demand.

Should be level of prices. Apologies.

Can the present inflation be attributed (at least in part) to costs of military keynesianism (in conjunction with US strategic delinking from China–not just temporary covid disruptions)?

“In my view, the current high inflation rates are likely to be ‘transitory’ because during 2022 growth in output, investment and productivity will probably start to drop back to ‘long depression’ rates. That will mean that inflation will also subside, although still be higher than pre-pandemic. Price controls will be ignored.”

My take is that inflation in the USA is permanent. Sure, some of the present-day inflation will disappear because Toyotism will be restored to some extent, but I don’t think it will be enough to offset all of it. My reasoning for that is precisely Marx’s Value Theory: value flows from the nation-states with less value (i.e. least industrialized) to nation-states with more value (i.e. more industrialized). The USA managed to “cheat the system” because it is the financial superpower: it printed the USDs to import the commodities it needed.

However, since more value than the USA “deserved” flowed to it, the result was an excess of containers at the gates of its ports (specially the Californian port, which is directed to China). Once the rest of the world realized those extra “sugar rush” USDs were hollow, they adjusted their productive chains and monetary policies to try to cancel them out, resulting in rising inflation in the USA.

The Dollar Standard worked the best in the 1990s, when the euphoria over the fall of the USSR took over and the rest of the world trembled before the USA’s military might. Back them, it was not a question if the Dollar Standard was legitimate or not, but what were the sacrifices necessary the rest of the world should make in order to satisfy it.

After 2012, the indisputable status of the Dollar Standard started to crumble because, at the same time the USA’s economy started to degrade, China’s economic rise started to give signs it was a serious process, and not the “chicken flight” pattern of the other “Emerging Economies”. As value starts to accumulate in China, it is to China that value produced in the rest of the world will have to start to flow if capitalism is to merely survive, let alone prosper.

The American people will have to get accustomed to consume less.

VK wrote: “Once the rest of the world realized those extra “sugar rush” USDs were hollow, they adjusted their productive chains and monetary policies to try to cancel them out, resulting in rising inflation in the USA…..

After 2012, the indisputable status of the Dollar Standard started to crumble because, at the same time the USA’s economy started to degrade, China’s economic rise started to give signs it was a serious process.”

If the first paragraph were accurate, then we should see the dollar depreciate vs other currencies in international markets in step with inflation. But we do not. We see the dollar depreciating in the second half 2020 (after reaching a peak), and actually gaining value vs international currencies as inflation picks up in 2021.

If the second paragraph were accurate, we should see acute dollar depreciation in the currency markets after 2012. In 2012 and part of 2013, we see the US dollar maintain a narrow trading range against other currencies; then in 2014 we get an uptick, peaking in Q3 2015, before turning down during the “shadow recession” of 2016. Another trading range gives way to a climb to the new peak in Q1 2020 where things turn down until Q3 2020 when a new rise is initiated.

That doesn’t mean that this depreciation can’t happen, just means it hasn’t happened and cannot be considered a cause of inflation.

I don’t think there’s a shred of evidence that any of the countries or blocs with a major currency (euro, yen, yuan, aus, pound) has altered a monetary policy to value production in the US; even less is there evidence that change in monetary exchange prices have had the slightest thing to do with US inflation.

OTOH, I think the price of oil, and the significance of the energy sector in the US (which has grown remarkably in this century), and the need of this sector to counteract its lower rates of return on assets, equity, and net plant and equipment because of the way above average organic composition of capital in the sector has everything to do with triggering inflation, like it did in the early and late 1970s.

Your observations are incorrect because the Dollar Standard – albeit dilapidated – still stands.

You would only be correct if the Dollar Standard suddenly ceased to exist in the periods you mention.

Besides, obviously, we’re not talking about Physics: there is a period of latency in the social world, and its developments are almost never linear. For example: in the aftermath of the 2008 meltdown, the USD actually got stronger; that was the last vote of blind faith from the rest of the world on the capacity of the USA to keep its political status as the “lonely superpower”. Those years were called in the USA (or at least the middle classes from NYC) the “Obama Recovery”.

The spike of the oil prices wasn’t the cause for the crisis of the 1970s.

Exactly my point: the dollar standard, and authority, and privilege still stands– contrary to YOUR position that “beginning in 2012, the dollar standard started to crumble.”

As for 2008, that wasn’t a question of blind faith, but rather that the Fed had the power to make dollars available through open ended currency swap lines which prevented the complete collapse of world trade. That power, and responsibility, falls to the world’s reserve currency, and to be a reserve currency you have to a) have sufficient global economic power and PROPERTY to make the currency usable in settling trades and b) allow the currency itself to be traded without restriction in the currency markets. Both a and b mean that the Yuan/renminbi is not going to be a reserve currency soon. CPC does not want unrestricted trading of its currency on international markets.

Might happen, but it will take a major depression and war to reconfigure the economy, if anything resembling one remains, in that direction.

As for oil, never claimed it caused the “crises” of the 1970s. Do claim it acted as an index to those difficulties, that its price inflation triggered price inflation throughout the capitalist world; that the price increases in 73, 79, 90-91, 99, 2005-2007 etc were attempts to balance out the lower rates of return in this technically intensive sector.

Michael Roberts says in his „Marxist theory of inflation“: “Money is endogenous to capitalist production and prices of production are formed from value creation not from money creation. Money supply generally will follow price changes, so deliberate attempts to alter the money supply will fail to determine price inflation.”

That is, in fact, the core of Karl Marx’s theory of money.

I have listed the development of Marx’s monetary theory in tabular form – albeit only in German, but my quotations from Marx can also be found in the English edition of the first volume of “Capital” and to understand my comments, a google translation may be enough.

look here:

https://marx-forum.de/Forum/index.php?thread/1067-karl-marx-und-der-goldstandard-update/&postID=5672#post5672

Wal Buchenberg, Hannover

Solid piece as always. 😀 Interesting article from a neoclassical perspective here: https://noahpinion.substack.com/p/why-price-controls-are-a-bad-tool/comments

Why not simply index? If your income rises in lockstep with prices, why need you worry about nominal inflation? Can’t we easily convert nominal prices to percent of income, and keep real purchasing power stable no matter how high or fast nominal prices may rise?

Generalized inflation is already a form of indexing. And what gets indexed most critically are interest rates, which winds up depreciating the nominal and market values of debt instruments. Next thing you know, you’re in the midst of another “liquidity” crisis as the debt service on these financial instruments exceeds the ability to realize any profit in the arbitrage of the instruments. Then your financial markets seize up, and the liquidity crisis reveals itself to be a solvency crisis.

It (the progression from illiquiditiy to insolvency) is going to happen, sooner or later, with or without indexing. But the bond markets call the tunes here and those markets know that indexing is just another name for haircut. If only Sweeny Todd were the barber.

Lost in all this economic bafflegab is any mention of who actually raises prices. Companies do—those few upper management people in charge. Price increases juice profits. Latest earnings report articles in the Wall Street Journal cite price increases as a factor in companies’ record profits. But let’s explain it to the great unwashed as some uncontrollable force of nature.

I like the footnote in Jeremy Rudd’s discussion paper posted on Fed Board’s website in Sept.

“I leave aside the deeper concern that the primary role of mainstream economics in our society is to provide an apologetics for a criminally oppressive, unsustainable, and unjust social order.”

Prices are ultimately limited by the law of value, not the will of individual capitalists, as exhaustively demonstrated by Marx in Capital. Managers increase (or decrease) prices when economic and social conditions, which are in aggregate beyond the control of any given individual or company, allow them to or the pressure of competition forces them to. The capitalist mode of production is not an automatic machine, decisions of individual capitalists do matter on a cultural and historical level, but there are definite constraints which must necessarily shape their decision making process at any given moment if they are to continue to be capitalist managers. That apologists of exploitation falsely compare these constraints (capitalist laws of motion) to forces of nature does not mean they don’t operate; the distinction is that these laws, unlike natural laws, are historically transient.

wont price controls work for petrol,diesel?

Controls can work for selected commodities and for a while, but they cannot work to drive aggregate inflation rates down without hitting overall profitability.

Interesting point by non Marxists

There is something that everyone is ignoring. If there is an increase in the interest rate, 15% or more of the zombie companies enter bankrupt in medium term. With this the remaining companies will rely on their profit rates, and inflation will continue.