The UK finally leaves the European Union on 31 December, after 48 years of membership (if you include joining the European Economic Community in 1973). The initial decision to leave, made in the special referendum back in June 2016, has taken over four tortuous years to implement. So what does the deal mean for British capital and labour?

For British manufacturers, the tariff-free regime of the EU’s internal market has been maintained. But the British government will have to renegotiate new bilateral treaties with governments across the world, whereas previously they were included within EU deals. People will no longer be able to work freely in both economies by right, all goods will require significant additional paperwork to cross borders and some will be checked extensively to verify they comply with local regulatory standards. Frictionless trade is over; indeed, that’s even between Northern Ireland and mainland Britain with a new customs border across the Irish Sea.

And that’s just goods trade, where the EU is the destination of 57% of British industrial goods. The British government fought tooth and nail to protect the fishing industry (and failed), but it contributes only 0.04% of UK GDP, while the services sector contributes over 70%. Of course, most of this is not exported, but still services exports contribute 30% to UK GDP. And 40% of that services trade is with the EU directly.

Indeed, while the UK runs a huge goods trade deficit with the EU, that is in part compensated by running a surplus in services trade with the EU. This surplus is in mainly financial and professional services where the City of London leads. Exports of UK financial services are worth £60 billion annually compared to imports of £15 billion. And 43% of financial services exports go to the EU.

The Brexit deal with the EU has done nothing for this sector. Professional services providers will lose their ability automatically to work in the EU after the Brexit deal failed to obtain pan-EU mutual recognition of professional qualifications. This means that professions from doctors and vets to engineers and architects must have their qualifications recognised in each EU member state where they want to work.

And the deal does not cover financial services access to EU markets, which is still to be determined by a separate process under which the EU will either unilaterally grant “equivalence” to the UK and its regulated companies or leave firms to seek permissions from individual member states. Over the next year, there may well be bit by bit agreements on trade in these areas. But the UK service sector is bound to end up worse off for its exports than was the case within the EU.

And that’s serious because the UK is a ‘rentier’ economy that depends heavily on its financial and business services sector. Financial services contribute 7% of UK GDP, some 40% higher a contribution than in Germany, France or Japan.

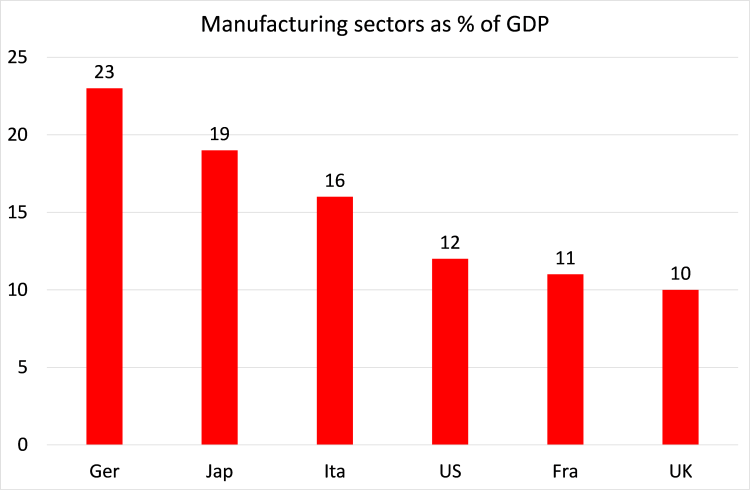

The UK is a country of bankers, lawyers, accountants and media people, rather than engineers, builders and manufacturers. The UK has a huge top-heavy banking sector, but a small manufacturing sector compared to other G7 economies.

What about the impact on working people? On leaving the EU, what little British labour has gained from EU regulations will be in jeopardy within a country which is already the most deregulated in the OECD. The EU rules included a 48-hour week maximum (riddled with exemptions); health and safety regulations; regional and social subsidies; science funding; environmental checks; and of course, above all, free movement of labour. All that is going or being minimised.

Around 3.7% of the total EU workforce – 3 million people – now work in a member state other than their own. Since 1987, over 3.3 million students and 470,000 teaching staff have taken part in the EU’s Erasmus programme. That programme will exclude Britons from now on. Immigration into the UK from EU countries has been significant; but it also works the other way; with many Brits working and living in continental Europe. With the UK out of the EU, Britons will be subject to work visas and other costs that will be greater than the total money per person saved from contributions to the EU.

On balance, EU immigrants (indeed all immigrants) have contributed more to the UK economy in taxes (income and VAT), in filling low-paid jobs (hospitals, hotels, restaurants, farming, transport) than they have taken up (in extra cost of schools, public services etc). That’s because most are young (often single) and help pay pension contributions for those Brits who are retired. The Brexit referendum has already brought about a sharp drop in net immigration into the UK from the EU, down 50-100,000 and still falling. That can only add to the loss of national income and tax revenues down the road.

Most sober estimates of the impact of leaving the EU suggest that the UK economy will grow more slowly in real terms than it would have done if it had remained a member. Mainstream economic institutes, including the Bank of England, reckon that there would be a cumulative loss in real GDP for the UK over the next ten to 15 years of between 4-10% of GDP from leaving the EU; or about 0.4% points off annual GDP growth. That’s a cumulative 3% of GDP loss per person, equivalent to about £1000 per person per year.

The UK’s Office for Budget Responsibility reckons that one third of this relative loss has already taken place because of the reduction in the pace of business investment since the referendum as domestic businesses stopped investing much, due to uncertainty about the Brexit deal along with a sharp drop in foreign inward investment.

And then of course, the COVID pandemic has decimated business activity. In 2020., the UK will suffer the largest fall in GDP among major economies apart from Spain and recover more slowly than others in 2021.

British capitalism was already slipping badly before the pandemic hit. Its trade deficit with the rest of the world had widened to around 6% of GDP; and real GDP growth had slid back from over 2% a year to below 1.5%, with industrial production crawling along at 1%. The UK economy already had weak investment and productivity growth compared with the 1990s and with other OECD countries.

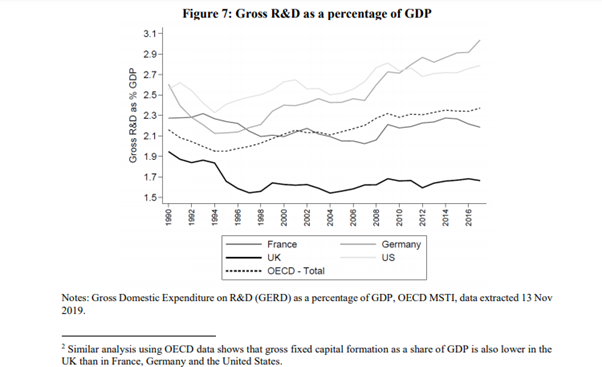

Investment in technology and R&D has been poor, more than one-third less than the OECD average.

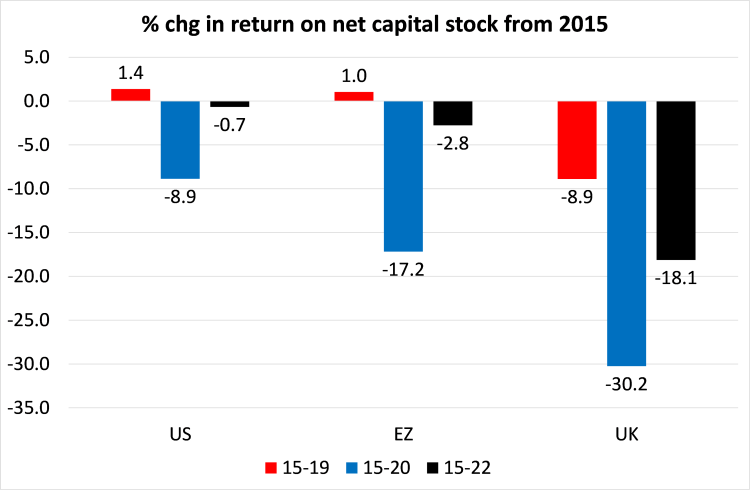

And the reason for this is clear. The average profitability of British capital has been falling. Even before the pandemic hit in 2020, average profitability (according to official statistics) was 30% below the level of the late 1990s and, excluding the Great Recession, was at an all-time low.

Since the referendum of 2016, UK profitability has fallen by nearly 9%, compared to small rises in the Eurozone and the US. And the Eurozone AMECO forecast for profitability will leave the UK 18% below 2015 levels by 2022!

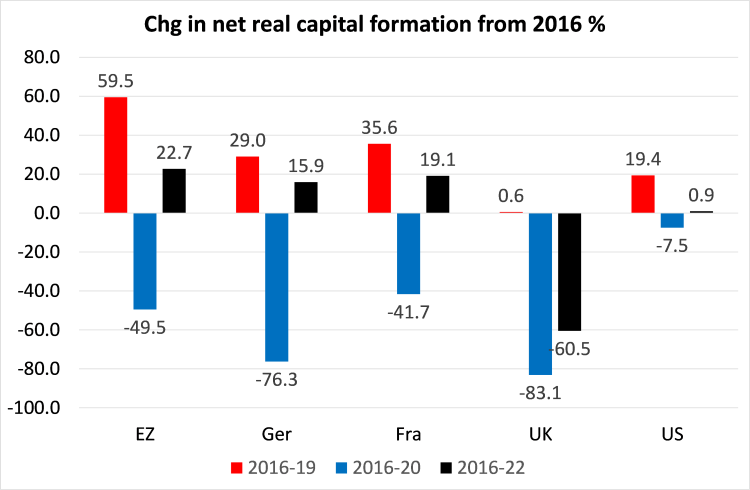

As a result, investment by British capital is set to plunge and is forecast to be down a staggering 60% by 2022 compared to the referendum year of 2016.

But maybe the UK can confound these dismal forecasts, as the government claims, because UK industry and the City of London can now expand across the world ‘free from the shackles’ of EU regulation. And it is increasingly clear how it thinks it can do this – by turning Britain into a tax and regulation-free base for foreign multinationals. The government is planning ‘free ports’ or zones; areas with little to no tax in order to encourage economic activity. While located geographically within a country, they essentially exist outside its borders for tax purposes. Companies operating within free ports can benefit from deferring the payment of taxes until their products are moved elsewhere or can avoid them altogether if they bring in goods to store or manufacture on site before exporting them again.

Unfortunately, for the government, studies show that free ports might simply defer the point when taxes are paid, as imports would still need to reach final customers across the country. And the incentives may also promote the relocation of activity that would have taken place anyway, from one part of the UK to another. Moreover, tax breaks could mean a loss of revenue for the Treasury. And free ports risk facilitating money laundering and tax evasion, as goods are usually not subject to checks that are standard elsewhere. A deregulated Britain will not restore economic growth, let alone good, well-paid jobs for an educated and skilled workforce. It will only boost the profits of multi-nationals, using cheap, unskilled labour.

In sum, the Brexit deal is another obstacle to sustained economic growth for Britain. But the COVID pandemic slump and the underlying weakness of British capital are much more damaging to the UK’s economic future than Brexit. Brexit is just an extra burden for British capital to face; as it also will be for British households.

Great summary, thank you. Abatement of knowledge flows via university-industry international networks will impact over time perhaps especially in pharmaceuticals, armaments (sadly) and fin-tech. Despair at neoliberal strategy and impact on workers and worry about EU’s responses, probably tightening up service regulations in attempt to build EU’s financial industries base. Back of queue in other country trade deals – especially China, who UK Government insist on annoying. All told, the rate of profit looks set to decline, but at a time when broad-based workers coalition badly led and organised and still with populist illusions. Sad times.

Very informative and nuanced view on the economic effects of the EU. While I think the claims that the EU and it’s various institutions have been prime architects of neoliberal dispossession, there is a somewhat nuanced reality that the U.K benefitted from some of the more social democratic tendencies and consumer protections that were more prevalent in other European states. It’s funny to see those who still claim the Tories are going to move to a “populist” economic right direction, when they are clearly just using that to obscure the fact that they are simply repeating patterns of neoliberal dispossession. Great piece!

I don’t see the consequences of Brexit just in the economy. In a global situation in which cooperation is increasingly important, Brexit is a step backwards towards “We are a big, better nation”.

For years and decades, the political class in UK and the British media mob blamed Brussels and the EU for all the home-made problems, even though every single provision and regulation that was passed in Brussels was approved by all EU governments, including the British Government. The referendum on Brexit was the result of this political irresponsibility.

I think the UK ruling class has still not digested the loss of its world domination. Britain’s exit from the EU will only accelerate the marginalization of England. The centrifugal (nationalist) forces in the world continue to grow. This is not a good development.

Wal Buchenberg, Hannover

‘’ The centrifugal (nationalist) forces in the world continue to grow. ’’

Accurate, brief and complete analysis. Centrifugal forces are not only a problem in the UK. The rise of the nationalist parties of Marie Lepen, Vox, Trump, etc. proves it. The processes for a Francexit, Spainexit, etc. are close. Why precisely now, in these decades, are there these centrifugal and nationalist forces? I do not know of studies on this subject and I only have little academic suspicions about it, but I believe that the demolition by harassment (in a cyclical regression of the predictable mode of production on the other hand) of the socialist model in Europe, and now in China, must have quite a relationship. In the same way that the construction of socialism had a lot to do with the construction of the European Union.

As a Greek and as a socialist, i can have absolutely no sympathy for the EU and the euro. It has decimated countless human lives and any hopeful prospect for entire nations. All in the name of a despicable bankocracy and the economic supremacy of Germany, which stands against the rest of the european nations as Prussia used to stand against the german ones. The idea that Britain cannot prosper outside the EU is laughable. The closest Britain ever came to (state) socialism, the best years for british workers and british households, was long before the EU and during the dissolution of the Empire. Its just that the UK needs an entirely different ecomomic model. And an entirely different social class to implement it.

British capital cannot prosper in or out would be my point

I have to agree with Giorgos. The EU is an alliance of capitalists, for capitalists, by capitalists. While we can point to the reactionary appeals of the “Leave” campaign, and oppose that reaction, staying in the EU itself is not “progressive;” and holds no prospects for the working class except the prospect of being subject to “Troikas” and austerity like that imposed on the people of Greece

On the plus side, the Brexit deal is a fine memento of a rare event where ordinary people had been once again briefly in charge, a principle that is meant to be the basis of democracy. Brexit had indeed sent lords, ladies, generals, bankers, lawyers, bishops, the media’s gurus and luvvies all scampering in a panic like field mice. This is probably the first time that there had been such widespread elite dismay in the UK since the General Strike of 1926. It should be a sight that heartens any Marxist or anybody who believes in people power.

I also dare to venture that your analysis is downplaying a benefit that was occurring even before the deal was struck. Rightly or wrongly, there is a political consensus now that capitalism will be only rescued by COVID vaccines. Outside of the EU’s rollout scheme, the UK currently has the most vaccinated population in Europe.

»people power in the service of the most rightist wings of the capitalist dictstorship« — what a riduculous idea! The rotten english monarchy leading the working class under its protective wings of deception«

how riduculous!

It is important to distinguish between a business deal and a trade deal. This agreement is a business deal not a trade deal. A business deal is where previous partners agree to diverge, whereas with a trade deal future partners agree to converge. A business deal is also broader because of its history. The most consequential aspect is legal enforcement. A business deal requires stronger legal enforcement to prevent previous partners taking advantage of each other which is after all the intention behind any commercial divorce. And yet this agreement is legal lite, with pop up arbitration. And it relies on the element of good faith which is always absent when countries seek to assert their sovereignty. Britain, by going to the wire has won a Pyrrhic victory on enforcement because this four year deal will end in acrimony, oh yes comrades, this is not a permanent deal, it has a four year break clause. Johnson may think that he has sorted out the European question, but he has not. So not only will relations with Europe deteriorate he has now gone out of his way to antagonize China which will become the biggest economy in the next five years.

All of this can be seen in my latest posting. Populists always represent a deep crisis within capitalism while deepening it with their foolishness, and to mask what is happening, they joyously proclaim renewal and opportunity. Such is the stuff of revolution.

is there a difference between the gini that measures income distribution and calls it wealth and actual ownership of resources (real wealth) is it true that the gini can be constant but wealth accumulation is not. What index is used for wealth.

Thought you might know the answer. Find the blog very useful. Thank you.

Capital size, capital size, and again capital size are decisive in the world market.

In principle, therefore, the same applies to the UK capitalists as to the capitalists in Greece, Poland, Hungary, Latvia etc .: If they are not strong enough to assert their (special) interests within the EU state alliance, then they are certainly not strong enough to assert their special interests outside the EU and against the EU.

Wal Buchenberg, Hannover

Over here in the States, Wall Street and most “progressive” leaders have supported globalization. They have no concern for the outsourcing that helped kill manufacturing in the U.S.

In the 19th century the Luddites fought against machines to save their manual jobs.

Today’s Luddites are fighting globalization to save manual jobs.

It’s a fight against windmills.

The EU was only created in 1993 so it couldn’t possibly be 48 years old!

Tony, you are the same person as the little boy you have been as toddler. You evolved.

The same occurred with the European Economic Community formed 1957 in Rome. It grew up and changed again and again and again. Becoming something different and always remaining the same.