Back in July, I wrote a post on a new approach to a world rate of profit and how to measure it. I won’t go over the arguments again as you can read that post and previous ones on the subject. But in that July post, I said I would follow up on the decomposition of the world rate of profit and the factors driving it. And I would try to relate the change in the rate of profit to the regularity and intensity of crises in the capitalist mode of production. And I would consider the question of whether, if there is a tendency for the rate of profit to fall as Marx argued, it could reach zero eventually; and what does that tell us about capitalism itself? I am not sure I can answer all those points in this post, but here goes.

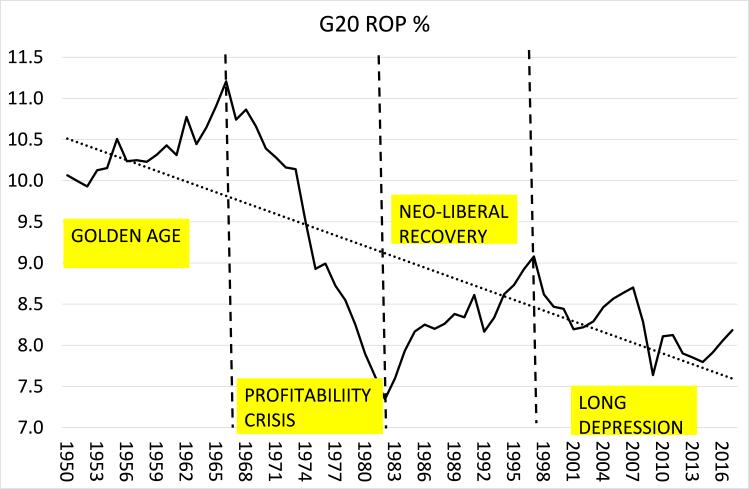

First, let me repeat the results of the measurement of a world rate of profit offered in the July post. Based on data now available in Penn World Tables 9.1 (IRR series), I calculated that the average (weighted) rate of profit on fixed assets for the top G20 economies from 1950 to 2017 (latest data) looked like this in the graph below.

Source: Penn World Tables, author’s calculations

I have divided the series into four periods that I think define different situations in the world capitalist economy. There is the ‘golden age’ immediately after WW2 where profitability is high and even rising. Then there is the now well documented (and not disputed) collapse in the rate of profit from the mid-1960s to the global slump of the early 1980s. Then there is the so-called neoliberal recovery where profitability recovers, but peaks in the late 1990s at a level still well below the golden age. And finally, there is the period that I call the Long Depression where profitability heads back down, with a jerk up from the mild recession of 2001 to 2007, just before the Great Recession. Recovery in profitability since the end of the GR has been miniscule.

So Marx’s law of profitability is justified empirically. But is it justified theoretically? Could there be other reasons for the secular fall in profitability than those proposed by Marx. Marx’s theory was that capitalists competing with each other to increase profits and gain market share would try to undercut their rivals by reducing costs, particularly labour costs. So investment in machinery and technology would be aimed at shedding labour – machines to replace workers. But as new value depends on labour power (machines do not create value without labour power), there would be a tendency for new value (and particularly surplus value) to fall relatively to the increase in investment in machinery and plant (constant capital in Marx’s terms).

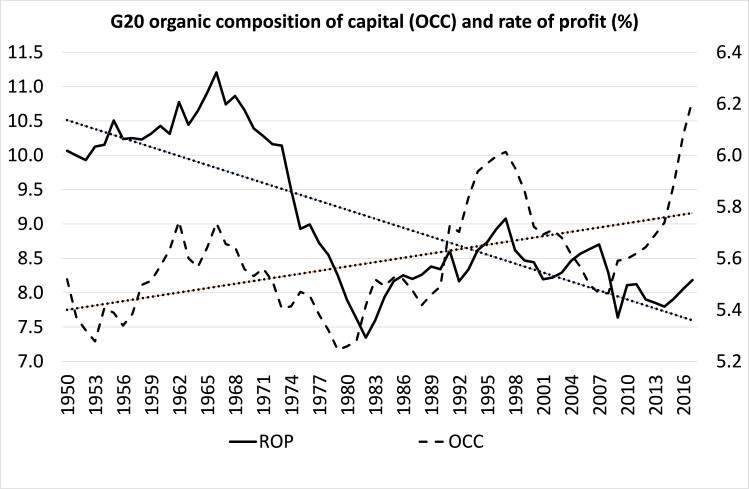

So over time, there would be a rise in constant capital relative to investment in labour (variable capital) ie a rise in the organic composition of capital (OCC). This was the key tendency in Marx’s law of profitability. This tendency could be counteracted if capitalists could force up the rate of exploitation (or surplus value) from the employed workforce. Thus if the organic composition of capital rises more than the rate of surplus value, the rate of profit will fall – and vice versa. If this applies to the rate of profit as measured, it lends support to Marx’s explanation of the falling rate of profit since 1950.

Well, here is a graph of the decomposition of the rate of profit for the G20 economies. The graph shows that the long-term decline in profitability is matched by a long-term rise in the OCC. So Marx’s main explanation for a falling rate of profit, namely a rise in the organic composition of capital is supported.

Source: Penn World Tables, author’s calculations

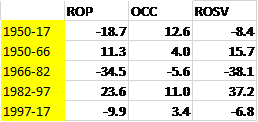

What about the rate of surplus value? If that rises faster than the OCC, the rate of profit should rise and vice versa. Well, here are the variables broken down into the four periods I described above. They show the percentage change in each period.

Source: Penn World Tables, author’s calculations

For the whole period 1950-2017, the G20 rate of profit fell over 18%, the organic composition of capital rose 12.6% and the rate of surplus value actually fell over 8%. In the golden age, the rate of profit rose 11%, because the rate of surplus value rose more (16%) than the OCC (4%). In the profitability crisis of 1966-82, the rate of profit plummeted 35% because, although the OCC also fell 6%, the rate of surplus value dropped 38%. In the neoliberal recovery period, the rate of profit rose 24% because although the OCC rose 11%, the rate of surplus value rose 37% (a real squeeze on workers wages and conditions). In the final period since 1997 when the rate of profit fell 10% to 2017, the OCC rose a little (4%) but the rate of surplus value dropped a little (7%).

These results confirm Marx’s law as an appropriate explanation of the movement in the world rate of profit since 1950 – I know of no other alternative explanation that explains this better.

So will the rate of profit eventually fall to zero and what does that mean? Well, if the current rate of secular fall in the G20 economies continues, it is going to take a very long time to reach zero – well into the next century! Among the G7 economies, however, if the average annual fall in profitability experienced in the last 20 years or so is continued, then the G7 rate will reach zero by 2050. But of course, there could be a new period of revival in the rate of profit, probably driven by the destruction of capital values in a deep slump and by a severe restriction on labour’s share of value by reactionary governments.

Nevertheless, what the secular fall in the profitability of capital does tell you is that capitalism’s ability to develop the productive forces and take billions out of poverty and towards a world of abundance and harmony with nature is hopelessly impossible. Capitalism as a system is already past its sell-by date.

Finally, can we relate falling profitability with regular and recurring crises of production and investment in capitalism? In my book, Marx 200, I explain that connection and in the July post I showed a close correlation between falling profitability of capital and a fall in the total mass of profits. Marx argued that, as average profitability of capital in an economy falls, capitalists compensate for this by increasing investment and production to boost the mass of profit. He called this a double edge law: falling profitability and rising profits. However, at a certain point, such is the fall in profitability that the mass of profits stops rising and starts to fall – this is the crux point for the beginning of an ‘investment strike’ leading to a slump in production, employment and eventually incomes and workers’ spending. Only when there is a sufficient reduction in costs for capitalists, bringing about a rise in profitability and profits, will the ‘business cycle’ resume.

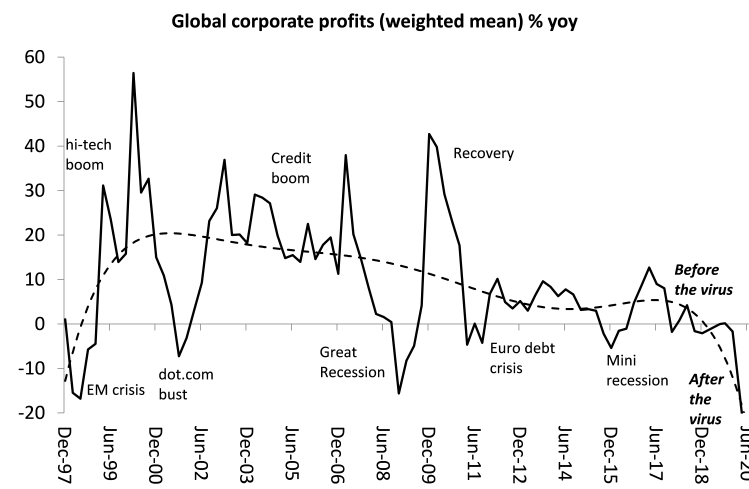

What is happening right now? Well, as we have seen above, global profitability was already at a low point in 2017 and still below the pre-Great Recession peak. By any measured guess, it was even lower in 2019. And I have updated my measure of the mass of profits in the corporate sector of the major economies (US, UK, Germany, Japan, China). Even before the pandemic broke and the lockdowns began, global corporate profits had turned negative, suggesting a slump was on its way in 2020 anyway.

We read about the huge profits that the large US tech and online distribution companies (FAANGS) are making. But they are the exception. Vast swathes of corporations (large and small) globally are struggling to sustain profit levels as profitability stays low and/or falls. Now the pandemic slump has driven global corporate profits down by around 25% in the first half of 2020 – a bigger fall than in the Great Recession.

Source: National accounts, author’s calculations

Profits recovered fast after the Great Recession. It may not be so quick this time.

Are there figures for China’s rate of surplus production in its state owned sector? Apparently the social surplus can be monetized and invested in the “capitalist” sector. Given present market conditions, has there been a movement toward more investment in China’s state sector (even from the market sector?)

Yes there is. The national bureau of statistics of China releases monthly profit figures which breaks down profits and their sources, private, state, foreign etc. Here is the link to the latest release on profits. http://www.stats.gov.cn/enGliSH/PressRelease/202008/t20200828_1786513.html It often comes as quite a surprise to first time readers of this report what a small proportion of the total state corporations generate.

Thank you for this link and the other. That small proportion is both surprising and not surprising. But it is somewhat modified by the joint state/private ventures, state banks and state ownership of the land. China made what I think was a necessary (nep style) faustian bargain that it has carried through to what seems to be the end game. Where China will go is anybody’s guess, but it would seem, given the current situation continuing with no war, that, as predicted by Amin, it will have to be either comprador or socialist.

fails to break the profits down as return on investment from tangible vs intangible profits. Rule of law continues to extract from the masses the bits of profits that belong to the masses, and to transport those massive numbers of iddy bitty bits into one big pot for the Oligarchs.. but in the 1955 physical assets were 87% of the balance sheet today it is 14% .. the ratio of tangible to intangible has been exchanged.. and that exchange has been the source of profit since the 1960s.. Now even extraction from the masses by rule of law cannot replace the profits that once were returned to competitive enterprise.. Furthermore that exchange of physical asset for intangible assets has changed capitalism from competitive to monopolism, feudalist not competitive.

Excellent point.

This analysis done in 2016 shows that on average the 25 most valuable (highest market capitalisation) corporations listed on the London Stock Exchange had physical/tangible assets which were worth at the end of 2015 only 8,6 per cent of total combined total assets.

http://edmundosullivan.com/economics2030/intangibles-dominate-britains-biggest-companies/

The shift in the capital structure of corporations away from tangibles to intangibles(including securities) is the most important development in capitalism in our era and a description of how corporations are responding to the declining rate of profit that Michael has diligently and convincingly exposed.

The logic driving those that manage corporate capital structures (and this is something I’ve witnessed first-hand in a 40 year business career) is as follows:

1) Reduce labour costs through wage freezes, redundancies and introducing labour-saving technologies. This produces one-off profit gains but does not prevent the long-term tendency for profitability to fall as Michael has explained.

2) Divest tangible assets (machinery etc) by shutting down factories and contracting out but (again) there is a limit to the extent this can deliver sustainable profit increases since at some point all physical assets will have been shut or closed. At this point, you have a firm which has no physical assets and only workers (good for profits). But it is a firm with no need for capital and therefore no need for capitalist investors. When this happens systematically, the system collapses.

This turning point was probably reached in the UK about 20 years ago (around the dotcom bubble)..

So why has the system survived?

The suggested answer is that corporations have developed a new way of generating returns for investors beyond tangible capital.

This has involved a process that’s been happening for decades of redefining balance sheet assets using intellectual property law (which now classifies as assets things that had previously been seen as ideas and essentially beyond capitalisation) and the assistance of co-operative legislatures persuaded of the imaginary existence of human capital.

Intangible capital maintains the enforceable property claims of investors over corporate profits (just like tangible capital does) plus it gives corporations the freedom (which tangibles do not allow) of moving assets from jurisdiction to jurisdiction (mainly to avoid tax).

This double benefit explains much of the appeal of Alphabet, Apple, Facebook etc.

Capitalism has developed a way of surviving beyond the point where return on tangible assets (foreseen by Marx) is the critical determinant of the system’s sustainability.

Owners of capital are securing profits from balance sheet manipulation and tax avoidance rather than directly from the labour process.

The good news is that this is a technical issue that can be addressed by legislatures and the courts.

In other words, the revolution’s already happened, but (perhaps) not in our heads..

The financialized system you accurately describe reminds me of the depiction of Socrates in Aristophanes’ “The Clouds,” where Socrates’ corruptible body floats about within a cloud of incorruptible soul. But in Plato’s Phaedo, Socrates is much more the sophist than the clown. Basically, Plato’s Socrates makes a case for the sanctity of the patriarchal state and its laws in maintaining the social/moral order in Athens, but says little about the division between slave and free citizen or aristocrat, or about how the former ‘s bodily labor serves the corruptible body of the latter, thereby freeing his soul to meditate (while munching on a flatbread) on Death: God, the Good, the True, the Eternal. Socrates downs the hemlock as a kind of salute to the Authority that made him who he really is, well fed, pure of soul.

Like Socrates (and Plato) who knew better, you chose to ignore the labor of the global south which is the body of Western disembodied wizardry, and leaves the reader hungry in Plato’s cave. But you must be ironic.

I would guess that the preponderance of the “fixed assets including software” you refer to belong to the IT/military industrial sector(s), as well as to the service providing platforms of the gig labor industry, since these sectors characterize the most salient aspects of the transformation of the US economy during the neoliberal period, especially from 2008 to the present, which Roberts calls “the long depression” (during which the real economy in the US [and the EU] has actually contracted.

Istvan Meszaros believe war production to be destructive (as opposed to) productive production. Much of the fixed asset values in the IT sector have been subsidized since the war-ending depression by the militarized/surveillance state. The question is, how do you theorized, economically and politically (i.e.as marxists) these quasi-fascist social developments?

Important point. After Michael provided me with the FED spreadsheet 5a, I analysed and reported on the changing relationship between produced assets and fictitious assets (financial and intangible). The period covered by the FED spans 1960 – 2019. According to the FED the share of these fictitious assets rose from 40% in 1960 to 67% of total assets by 2019. That is why the FED reported “complex” rate of return as found in Michael’s previous post is so low, because it is based on total assets including fictitious assets. I think the most important point my report shows is the behaviour of the real versus the complex rate of returns. The gap widens at the height of the boom only to collapse in the recession as fictitious capital is wiped out aligning real and total assets once more. Fictitious capital is a true phoenix rising again and again from the ashes of recession to ride the updrafts generated by the growth in the production of value. The link to my report is https://theplanningmotivedotcom.files.wordpress.com/2020/09/fed-derived-complex-rate-of-return.pdf

Not all financial assets are “fictitious capital”– some aren’t capital at all, or maybe all aren’t capital at all, simply parked revenues and profits, “waiting” to be deployed in investments or purchases..

If you look at the St. Louis Fred’s charts on nonfinancial corporations’ assets, you’ll see nonfinancial assets (the “hard assets”) increase from about $4 trillion in 1980 to $24 trillion in 2020. Financial assets increase from about $1 trillion to $21 trillion in the same period, certainly a more rapid gain, attributable in large part to increasing amounts of cash, short term paper, and other liquid instruments used to park large sums of money. Checkable deposits increase more than 30 fold in the 1980-2020 period to $1.7 trillion; time and saving deposits increase at approximately the same rate to about $280 billion. Money market mutual fund assets move from zero to $500 billion. Trade receivables– essentially billings awaiting payment expand 9 fold to $3.6 trillion; commercial paper increases 25X to $250 billion.

None of these are “fictitious” but are short term vehicles for holding cash, driven by the increasing masses of money thrown off by expanding circulation (“Circulation sweats money from every pore,” wrote Marx).

However, the largest increase is recorded in real estate assets (discontinued by FRED in 2015) expanding from 2 trillion in 1980, to about 11 trillion in 2015.

I think we would all do well to stop explaining capitalism’s persistence, survival, or even growth as a result of “fictitious capital.”

It would be interesting to know the nature of those non-financial assets that increased so dramatically in the US from 1980 to 2020. During that span the process of the deindustrialization of the core western states (beginning in the US) and the concentration of much of the world’s capital–industrial as well as financial–in exponentially growing financial institutions centered in the West. It is a process of slashing the value of precarious labor in the US and its allies (especially England and Germany) and improving the profitability of zombified firms that, as their (“fictitious?) values rise, are flipped like hot cakes by new “owners,” who are just as interested making interest from the debt they create in the firms they now own as from the firm’s profits–both extorted from shell-shocked labor.

In reply to mandm: Corporate fixed assets including software expand from 1.3 trillion in 1980 to 8 trillion in 2020. Inventories expand from 576 trillion to 2.6 trillion.

Could you please share the source of these figures?

“So investment in machinery and technology would be aimed at shedding labour – machines to replace workers. But as new value depends on labour power (machines do not create value without labour power), there would be a tendency for new value (and particularly surplus value) to fall relatively to the increase in investment in machinery and plant (constant capital in Marx’s terms).”

This is the part that I’m having trouble understanding. Let’s say you have a company that makes widgets, and has 100 employees and 100 machines. Now let’s say due to better technology the company is able to replace half of its employees with machines and still make the same amount of widgets. The company still makes the same amount of money, but now pays only half the labor costs, so it seems its profits have increased.

How does this match with the claim that a rise in the organic composition of capital causes a fall in the rate of profit? It seems that in this case the rising organic composition of capital has caused an increase in the rate of profit.

As I understand this: because of competition, eventually, majority of the producers adopt the new labour replacing machinery (that your original producer invented to replace half of workers), the price of the widgets falls, brining the profit rate down. The result is that these particular widgets are now produced by fewer workers with more machinery, and therefore, the extracted surplus labour is lower, and so are the profits. In the initial stage of adoption of new labour saving technology, the pioneering capitalists do rip higher than average profits, but that does not last, as producers with old technology, who have established market share, first lower prices and then also adopt new technology. Something like this..?

That makes sense but the reason the rate of profit is falling in this case isn’t because of the rising composition of capital, but merely the existence of competition. Even if no workers were replaced by machines, a competing capitalist could step in and offer a lower price, undercutting the original capitalist. But that would mean that the concept of “rising organic composition of capital” isn’t what is causing the rate of profit to fall, rather the mere existence of competition is.

Those machines will have been produced by many levels of previous labor, the value of which is composed of monetized labor power, the value of which is only potential until it is realized–not in the purchase of those 50 machines by the capitalist producer of the end product, but its consumer, who, in a mature capitalist system, would be (for the most part) wage earners, 50% of which would. have been shed, and replaced by machinery, in your example.

And how does this lead to a falling rate of profit for the capitalist?

Those 50 wage earners are more than a mere number representing saved expenditure on “human capital”. They are 50 unemployed human beings. Think historically and dialectically and historically, and, and above all, humanely, and work it out for youself.

Sorry. Too many “historicallys” in my reply. But one can never learn too much history.

One more point to help you along. Your example as it stands, is a kind of economic singularity. But placing it in the context of a social mode of production, it might help you explain why this singular (bug up the butt) capitalist decided to invest in expensive innovative, labor shedding machinery. An educated guess might lead you to consider a declining rate of profit (market competition? involuntary wage increases? both”?) Crises of overproduction and even financial crises are often the result of the efforts of a critical mass of capitaliss to overcome the falling rate of proft.

Competition on its own does not suffice to explain the falling rates of profit. Businesses are already competing and are selling at the lowest sustainable price for investing, and the rate of profit is constant because the ratio of investment into labor vs. fixed assets is unchanged. A new capitalist cannot simply step in and undercut an established market because that has already occurred to the point where undercutting is no longer advantageous. Going lower would mean losing money not only directly through a losing business but also through opportunity costs from eschewing investment in more profitable markets – or from investment into technology in the same market.

More profits can be achieved by new machinery, and the process and its consequences of rising OCC have been explained by Olya. The new tech then goes from being a profitable advantage to becoming a basic requirement. Without this process, the rates of profit remain as they are.

Wouldn’t that just drive the rate of profit to a constant value rather than causing it to fall? As an example let’s say Company A has 10 employees who are paid $10 and produce one widget each that sells for $15 for a rate of profit of 33%. Then let’s say it is able to use technology to cut the number of employees in half, so its profit rate doubles to 66%. But since the widgets can now be sold for less, another company comes in and undercuts company A. But the most they would be able to do is drive the profit rate back to 33%, since any lower is no longer advantageous. So the rising organic composition of capital hasn’t led to a falling rate of profit, just a temporary raise followed by a return to the base rate.

Hi joe1445,

Marx defines the rate of profit as the rate of surplus value (proportion of surplus labor to necessary labor) divided by machines (constant capital) plus wages (variable capital). It can expressed as (v * s’) / (c + v) or (s / C). In your example, assuming $100 for machines, $100 for wages, and a rate of surplus value at 50%, the rate of profit before and after looks like this:

Before new technology:

( $100 * .5 ) / ( $100 + $100 ) = .25%

After new machines replace half of the workforce:

( $50 * .5) / ( $100 + $50) = .16%

So despite the savings in labor costs, the rate of profit drops from 25% to 16% as the organic composition of capital increases. What Marx argues here is that as technology increases productivity, capitalism in its entirety will have a tougher finding surplus value to realize as profit without resorting to creative workarounds. Some individual capitals will certainly benefit from early production advancements, but over time the tendency prevails.

You can also reference Capital Vol. 3 chapter 15.

Thank you for your detailed response. There are still a few points that I’m unclear on. First, what do “surplus labor” and “necessary labor” correspond to? Apologies for asking such simple questions but I’ve been reading this stuff for a while and have found it rather difficult to make sense of what is going on, so any clarification is greatly appreciated.

Necessary-labor refers to the portion of the working day required to reproduce labor for subsequent working days (to survive), and surplus-labor refers to the duration beyond that point. “Surplus-value” refers to the value produced by surplus-labor. Marx defines the terms starting in Capital volume 1, chapter 7.

You’re asking perfectly good questions. Like any argument, it’s important to understand how the terms are defined before you can analyze it constructively. I would highly recommend not relying exclusively on definitions from anyone (including mine), especially from sources that are explicitly anti-marxist, since virtually all of them either distort or ignore what Marx actually argues. Instead, have a primary source nearby and refer to it whenever in doubt.

You can get sources here (pdf, ebook, etc):

Capital Volume I: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/index.htm

Capital Volume II: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1885-c2/index.htm

Capital Volumne III: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1894-c3/index.htm

Also, regarding the tendency for the rate of profit to fall, I meant to refer you to Capital volume III, chapter 13 — though chapters 14 and 15, where he discusses the law’s implications, may be more interesting.

Perhaps the swings in the rate of surplus value should be correlated with major changes in demographic structure, the entry of women en masse into the labor force and the trend towards service industries? In particular, service industries seem better suited for valorizing a large amount of labor power…but they don’t seem as amenable to speed up and stretch out as standard commodity production. Does this trend drive up the relative importance of secondary forms of exploitation up, in particular credit card usury, education swindling, real estate manipulation and pension fund looting?

Bruce, Are there other counteracting processes besides increasing the rate of exploitation? Lenny

Michael, I was wondering what you think about the idea (proposed by Yanis Varoufakis) that 2008 marked the beginning of the post-capitalist era, that the financial sector has completely decoupled itself from the real economy with no prospect of return, that political power is now directly implicated in providing life-support to financial markets and the economy (QE, etc.), that an economic crisis required to shed old capital and reinvigorate the rate of profit is unlikely now to occur, and that this dynamic will play itself out through political conflict (with high probability resulting in fascism or high tech feudalism or something like that).

Michael— The numbers for the deep stagflation crisis of the ‘70s (1966-82) are surprising, While OCC was down 6%, the ROSV was WAY down (38%). I recently used your data to argue that the long term profitability crisis began with a sharply falling ROP in that period prior to the neoliberal turn. The consensus opinion was that the OPEC oil embargo, wage pressure from strong unions, and the dollar devaluation of ‘71, drove down the ROSV (profits) and this combination led to stagflation. I countered that the falling ROP ante-dated the other factors, so the recession was really one of falling profitability. Since this was the start of a secular process perhaps you could comment or write something on this period (“the winter of discontent” in the UK)

Hi Bob. Yes the fall in the ROSV at least on this Penn Tables measure is surprising. Of course, the factors you mention did play a role in a fall in the ROSV from the mid-1960s, but I find that the largest part of the fall was during the recessions of 1974-5 and 1980-2. There are two things to add. 1) I am still unhappy about the decomposition data from the Penn Tables so more work is needed here. 2) nevertheless, it is clear from the data that the ROP has had a secular fall and that the periods of decline coincide with greater rises (or less falls) in the OCC than with the ROSV. I shall return to these matters and make some revisions later this year.

Another thought I had is that when you say “profit rate” there are a few different things you may be referring to. In my above post I calculated “profit rate” as net revenue divided by gross revenue. Apparently the Marxist definition is different and I’m wondering what practical difference there is between the two definitions. Additionally it seems to me that the main thing driving investment should be rate of return on investment, which would be calculated as net revenue divided by total expenses.

Dear Teacher Roberts

I am editor of the Brazilian blog “Science and Revolution”, we recently translated a post for you, entitled -Engels in Nature and Humanity-, which we have attached, we would like your permission to translate this post as well. We always resonate your posts on our blog.

Hi Chico. Sure please go ahead and translate any post you like. Let me know when you publish

Thanks teacher .

Whenever we publish we will comment here. One day we would very much like an interview with you, especially addressing the question of Trotsky’s phrase about the productive forces “The productive forces have stopped growing”

Sure I can do a an interview

Thanks teacher

I will prepare some questions

Is there such a thing as a Marxist investment strategy? Could a hedge fund accept this is how things are, and use it to maximise returns?

Hello. I am doing a research paper on the falling rate of profit. I have skimmed many of your posts but I can’t seem to find concrete methods anywhere. I say this not to be accusatory, but out of genuine curiosity. If it’s at all possible, could you leave me a comment or DM me explaining your methodology specifically? As in, what did the equation look like and what was the meaning of each of your variables? Thank you for the consideration.