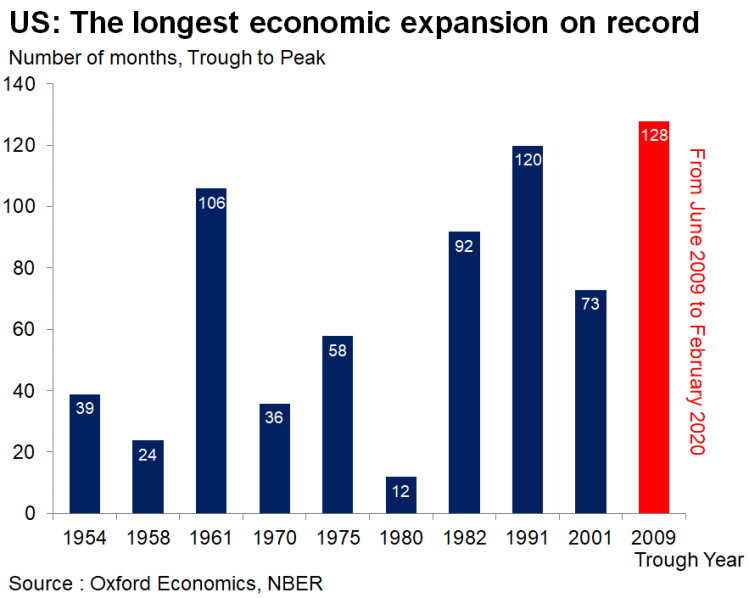

The coronavirus pandemic marks the end of longest US economic expansion on record, and it will feature sharpest economic contraction since WWII.

The global economy was facing the worst collapse since the second world war as coronavirus began to strike in March, well before the height of the crisis, according to the latest Brookings-FT tracking index.

2020 will be the first year of falling global GDP since WWII. And it was only the final years of WWII/aftermath when output fell.

JPMorgan economists reckon that the pandemic could cost world at least $5.5 trillion in lost output over the next two years, greater than the annual output of Japan. And that would be lost forever. That’s almost 8% of GDP through the end of next year. The cost to developed economies alone will be similar to that in the recessions of 2008-2009 and 1974-1975. Even with unprecedented levels of monetary and fiscal stimulus, GDP is unlikely to return to its pre-crisis trend until at least 2022.

The Bank for International Settlements has warned that disjointed national efforts could lead to a second wave of cases, a worst-case scenario that would leave US GDP close to 12% below its pre-virus level by the end of 2020. That’s way worse than in the Great Recession of 2008-9.

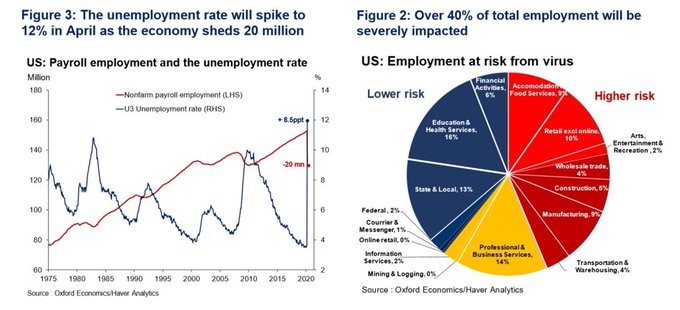

The US economy will lose 20m jobs according to estimates from @OxfordEconomics, sending unemployment rate soaring by greatest degree since Great Depression and severely affecting 40% of jobs.

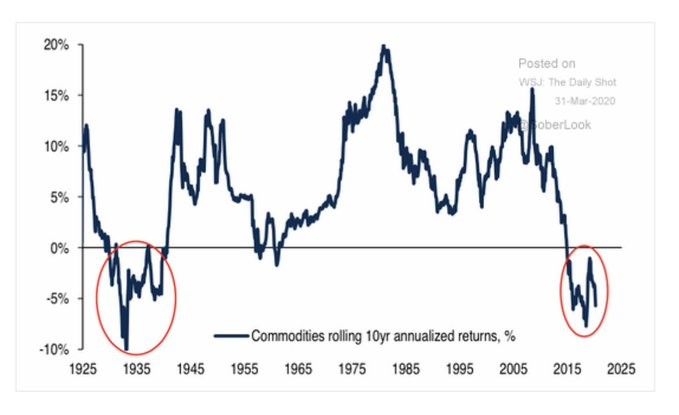

And then there is the situation for the so-called ‘emerging economies’ of the ‘Global South’. Many of these are exporters of basic commodities (like energy, industrial metals and agro foods) which, since the end of the Great Recession have seen prices plummet.

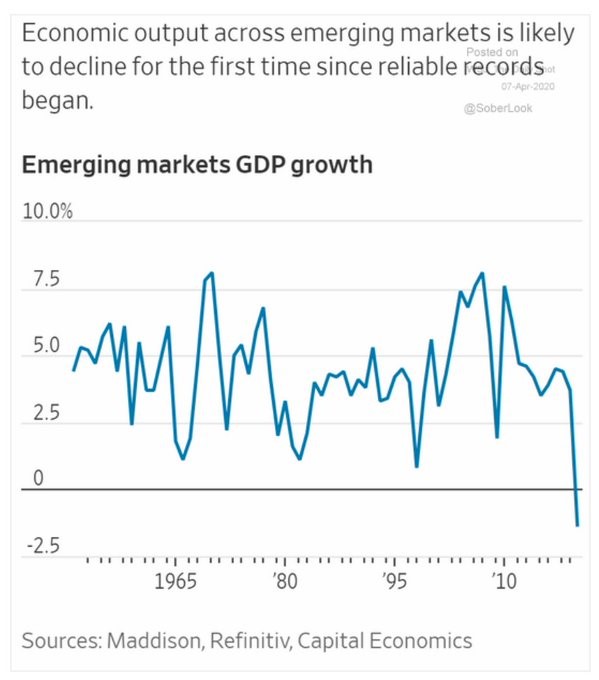

And now the pandemic is going to intensify that contraction. Economic output in emerging markets is forecast to fall 1.5% this year, the first decline since reliable records began in 1951.

The World Bank reckons the pandemic will push sub-Saharan Africa into recession in 2020 for the first time in 25 years. In its Africa Pulse report the bank said the region’s economy will contract 2.1%-5.1% from growth of 2.4% last year, and that the new coronavirus will cost sub-Saharan Africa $37 billion to $79 billion in output losses this year due to trade and value chain disruption, among other factors. “We’re looking at a commodity-price collapse and a collapse in global trade unlike anything we’ve seen since the 1930s,” said Ken Rogoff, the former chief economist of the IMF.

More than 90 ‘emerging’ countries have inquired about bailouts from the IMF—nearly half the world’s nations—while at least 60 have sought to avail themselves of World Bank programs. The two institutions together have resources of up to $1.2 trillion that they have said they would make available to battle the economic fallout from the pandemic, but that figure is tiny compared with the losses in income, GDP and capital outflows.

Since January, about $96 billion has flowed out of emerging markets, according to data from the Institute of International Finance, a banking group. That’s more than triple the $26 billion outflow during the global financial crisis of a decade ago. “An avalanche of government-debt crises is sure to follow”, he said, and “the system just can’t handle this many defaults and restructurings at the same time” said Rogoff.

Nevertheless, optimism reigns in many quarters that once the lockdowns are over, the world economy will bounce back on a surge of released ‘pent-up ‘ demand. People will be back at work, households will spend like never before and companies will take on their old staff and start investing for a brighter post-pandemic future.

As the governor of the Bank of (tiny) Iceland put it: “The money that now being saved because people are staying at home won’t disappear – it will drip back into the economy as soon as the pandemic is over. Prosperity will be back.” This view was echoed by the helmsman of the largest economy in the world. US Treasury Secretary Mnuchin spoke bravely that : “This is a short-term issue. It may be a couple of months, but we’re going to get through this, and the economy will be stronger than ever,”

Former Treasury Secretary and Keynesian guru, Larry Summers, was in tentative concurrence: “the recovery can be faster than many people expect because it has the character of the recovery from the total depression that hits a Cape Cod economy every winter or the recovery in American GDP that takes place every Monday morning.” In effect, he was saying that the US and world economy was like Cape Cod out of season; just ready to open in the summer without any significant damage to businesses during the winter.

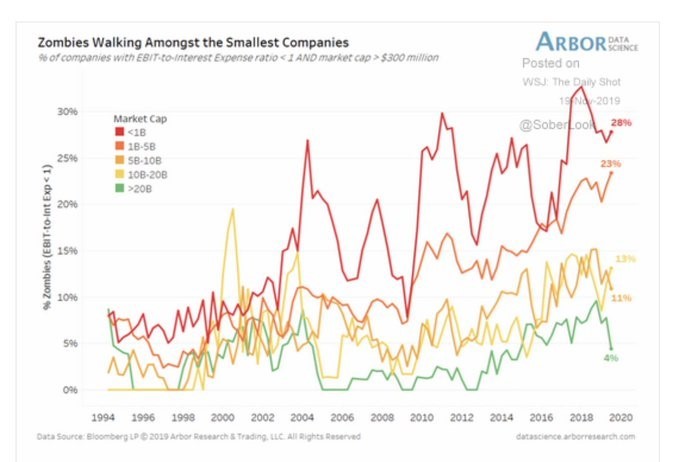

That’s some optimism. For when these optimists talk about a quick V-shaped recovery, they are not recognising that the COVID-19 pandemic is not generating a ‘normal’ recession and it is hitting not a just a single region but the entire global economy. Many companies, particularly smaller ones, will not return after the pandemic. Before the lockdowns, there were anything between 10-20% of firms in the US and Europe that were barely making enough profit to cover running costs and debt servicing. These so-called ‘zombie’ firms may have found the Cape Cod winter the last nail in their coffins. Already several middling retail and leisure chains have filed for bankruptcy and airlines and travel agencies may follow. Large numbers of shale oil companies are also under water (not oil).

As leading financial analysts Mohamed El-Erian concluded: “Debt is already proving to be a dividing line for firms racing to adjust to the crisis, and a crucial factor in a competition of survival of the fittest. Companies that came into the crisis highly indebted will have a harder time continuing. If you emerge from this, you will emerge to a landscape where a lot of your competitors have disappeared.”

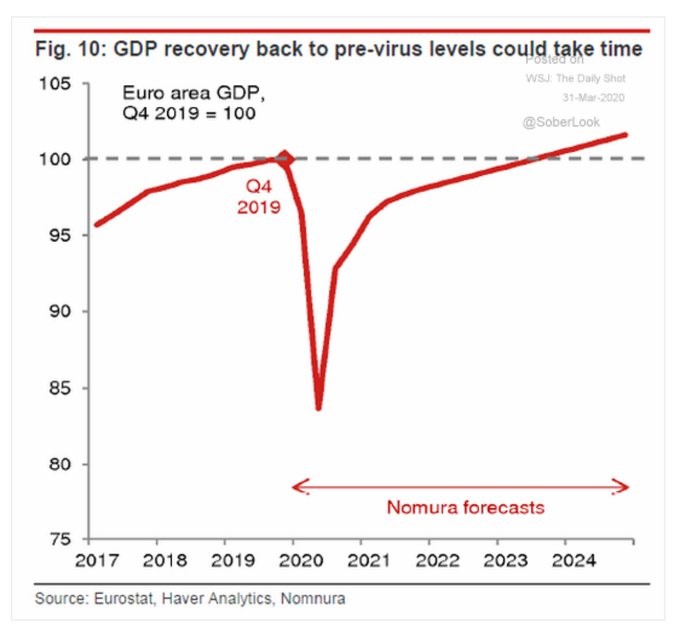

So it’s going to take a lot longer to return to previous output levels after the lockdowns. Nomura economists reckon that Eurozone GDP is unlikely to exceed Q42019 level until 2023!

And remember, as I explained in detail in my book The Long Depression, after the Great Recession there was no return to previous trend growth whatsoever. When growth resumed, it was at slower rate than before.

Since 2009, US per capita GDP annual growth has averaged 1.6%. At the end of 2019, per capita GDP was 13% below trend growth prior to 2008. At the end of the 2008–2009 recession it was 9% below trend. So, despite a decade-long expansion, the US economy fell further below trend since the Great Recession ended. The gap is now equal to $10,200 per person—a permanent loss of income. And now Goldman Sachs is forecasting a drop in per capita GDP that would wipe out all the gains of the last ten years!

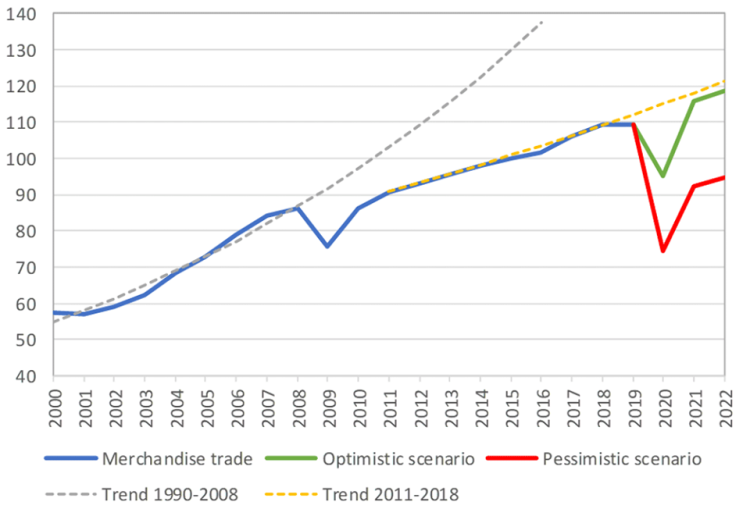

Then there is world trade. Growth in world trade has been barely equal to growth in global GDP since 2009 (blue line), way below its rate prior to 2009 (dotted line). Now even that lower trajectory (dotted yellow line). The World Trade Organisation sees no return to even this lower trajectory for at least two years.

But what about the humungous injections of credit and loans being made by the central banks around the world and the huge fiscal stimulus packages from governments globally. Won’t that turn things round quicker? Well, there is no doubt that central banks and even the international agencies like the IMF and the World Bank have jumped in to inject credit through the purchases of government bonds, corporate bonds, student loans, and even ETFs on a scale never seen before, even during the global financial crisis of 2008-9. The Federal Reserve’s treasury purchases are already racing ahead of previous quantitative easing programmes.

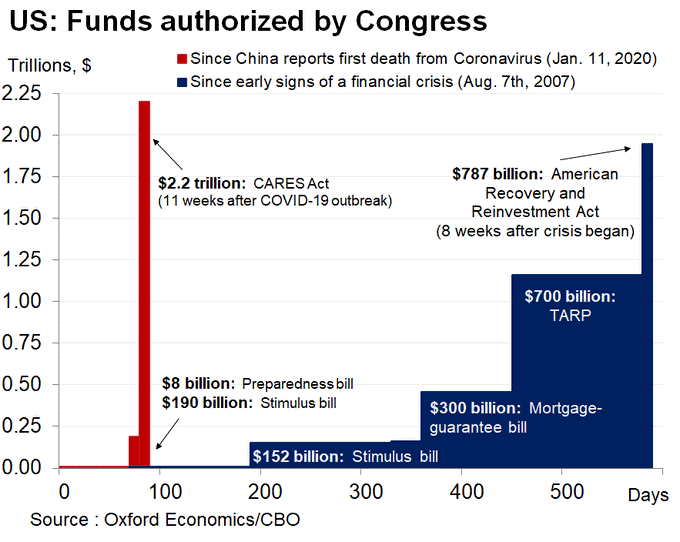

And the fiscal spending approved by the US Congress last month dwarfs the spending programme during the Great Recession.

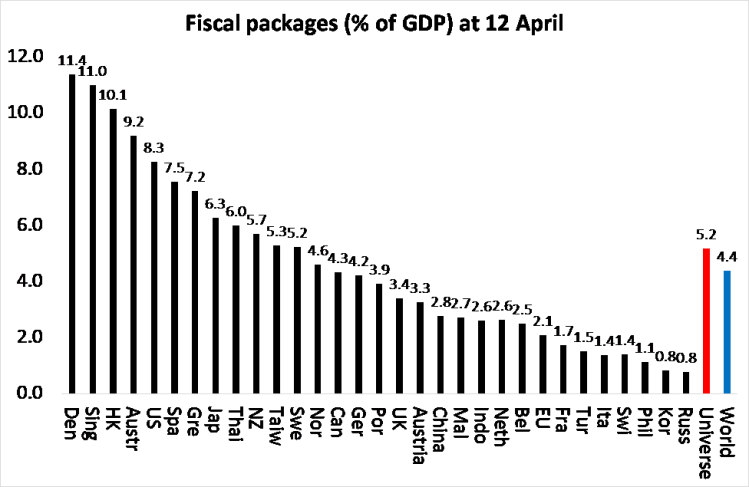

I have made an estimate of the size of credit injections and fiscal packages globally announced to preserve economies and businesses. I reckon it has reached over 4% of GDP in fiscal stimulus and another 5% in credit injections and government guarantees. That’s twice the amount in the Great Recession, with some key countries ploughing in even more to compensate workers put out of work and small businesses closed down.

These packages go even further in another way. Straight cash handouts by the government to households and firms are in effect what the infamous free market monetarist economist Milton Friedman called ‘helicopter money’, dollars to be dropped from the sky to save people. Forget the banks; get the money directly into the hands of those who need it and will spend.

In addition, suddenly the idea, which up to now was rejected and dismissed by mainstream economic policy, has become highly acceptable, namely fiscal spending financed, not by the issue of more debt (government bonds), but by simply ‘printing money’, ie the Fed or the Bank of England deposits money in the government account to spend.

Keynesian commentator Martin Wolf, having sniffed at MMT before, now says: “abandon outworn shibboleths. Already governments have given up old fiscal rules, and rightly so. Central banks must also do whatever it takes. This means monetary financing of governments. Central banks pretend that what they are doing is reversible and so is not monetary financing. If that helps them act, that is fine, even if it is probably untrue. …There is no alternative. Nobody should care. There are ways to manage the consequences. Even “helicopter money” might well be fully justifiable in such a deep crisis.”

The policies of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) have arrived! Sure, this pure monetary financing is supposed to be temporary and limited but the MMT boys and girls are cock a hoóp that it could become permanént, as they advocate. Namely governments should spend and thus create money and take the economy towards full employment and keep it there. Capitalism will be saved by the state and by modern monetary theory.

I have discussed in detail in several posts the theoretical flaws in MMT from a Marxist view. The problem with this theory and policy is that it ignores the crucial factor: the social structure of capitalism. Under capitalism, production and investment is for profit, not for meeting the needs of people. And profit depends on the ability to exploit the working class sufficiently compared to the costs of investment in technology and productive assets. It does not depend on whether the government has provided enough ‘effective demand’.

The assumption of the radical post-Keynesian/MMT boys and girls is that if governments spend and spend, it will lead to households spending more and capitalist investing more. Thus, full employment can be restored without any change in the social structure of an economy (ie capitalism). Under MMT, the banks would remain in place; the big companies, the FAANGs would remain untouched; the stock market would roll on. Capitalism would be fixed with the help of the state, financed by the magic money tree (MMT).

Michael Pettis is a well-known ’balance sheet’ macro economist based in Beijing. In a compelling article, entitled MMT heaven and MMT hell, he takes to task the optimistic assumption that printing money for increased government spending can do the trick. He says: “the bottom line is this: if the government can spend these additional funds in ways that make GDP grow faster than debt, politicians don’t have to worry about runaway inflation or the piling up of debt. But if this money isn’t used productively, the opposite is true.

He adds: “creating or borrowing money does not increase a country’s wealth unless doing so results directly or indirectly in an increase in productive investment… If U.S. companies are reluctant to invest not because the cost of capital is high but rather because expected profitability is low, they are unlikely to respond to the trade-off between cheaper capital and lower demand by investing more.” You can lead a horse to water, but you cannot make it drink.

I suspect that much of the monetary and fiscal largesse will end up either not being spent but hoarded, or invested not in employees and production, but in unproductive financial assets – no wonder the stock markets of the world have bounced back as the Fed and the other central banks pump in the cash and free loans.

Indeed, even leftist economist Dean Baker doubts the MMT heaven and the efficacy of such huge fiscal spending. “It is actually possible that we could be seeing too much demand, as a burst of post-shutdown spending outstrips the immediate capacity of the restaurants, airlines, hotels, and other businesses. In that case, we may actually see a burst of inflation, as these businesses jack up prices in response to excessive demand.” – ie MMT hell. So he concludes that “generic spending is not advisable at this point.”

Well, the proof of the pudding is in its eating and we shall see. But the historical evidence that I and others have compiled over the last decade or more, shows that the so-called Keynesian multiplier has limited effect in restoring growth, mainly because it is not the consumer who matters in reviving the economy, but capitalist companies.

And there’s new evidence on the power of Keynesian multiplier. It’s not been one to one or more, as often claimed, ie. 1% of GDP increase in government spending does not lead to a 1% of GDP increase in national output. Some economists looked at the multiplier in Europe over the last ten years. They concluded that “in contrast to previous claims that the fiscal multiplier rose well above one at the height of the crisis, however, we argue that the ‘true’ ex-post multiplier remained below one.”

And there is little reason that it will be higher this time round. In another paper, some other mainstream economists suggest that a V-shaped recovery is unlikely because “demand is endogenous and affected by the supply shock and other features of the economy. This suggests that traditional fiscal stimulus is less effective in a recession caused by our supply shock. … demand may indeed overreact to the supply shock and lead to a demand-deficient recession because of “low substitutability across sectors and incomplete markets, with liquidity constrained consumers.” so that “various forms of fiscal policy, per dollar spent, may be less effective”.

But what else can we do? So “despite this, the optimal policy to face a pandemic in our model combines as loosening of monetary policy as well as abundant social insurance.” And that’s the issue. If the social structure of capitalist economies is to remain untouched, then all you are left with is printing money and government spending.

Perhaps the very depth and reach of this pandemic slump will create conditions where capital values are so devalued by bankruptcies, closures and layoffs that the weak capitalist companies will be liquidated and more successful technologically advanced companies will take over in an environments of higher profitability. This would be the classic cycle of boom, slump and boom that Marxist theory suggests.

Former IMF chief and French presidential aspirant, the infamous Dominique Strauss-Kahn, hints at this: “the economic crisis, by destroying capital, can provide a way out. The investment opportunities created by the collapse of part of the production apparatus, like the effect on prices of support measures, can revive the process of creative destruction described by Schumpeter.”

Despite the size of this pandemic slump, I am not sure that sufficient destruction of capital will take place, especially given that much of the bailout funding is going to keep companies, not households, going. For that reason, I expect that the ending of the lockdowns will not see a V-shaped recovery or even a return to the ‘normal’ (of the last ten years).

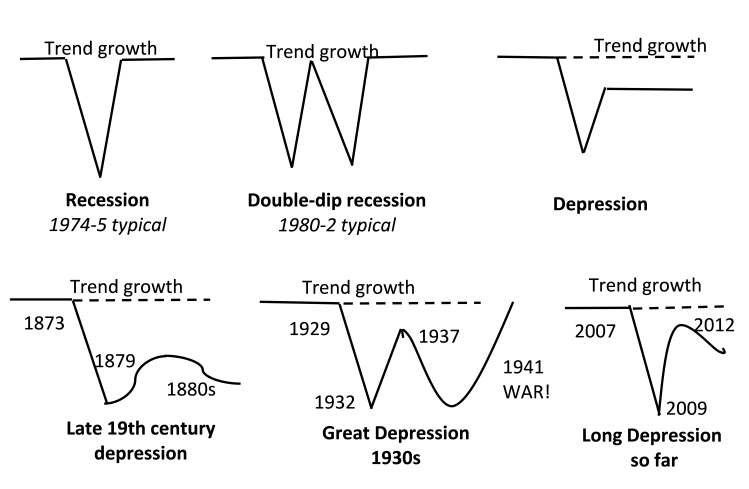

In my book, The Long Depression, I drew a schematic diagram to show the difference between recessions and depressions. A V-shaped or a W-shaped recovery is the norm, but there are periods in capitalist history when depression rules. In the depression of 1873-97 (that’s over two decades), there were several slumps in different countries followed weak recoveries that took the form of a square root sign where the previous trend in growth is not restored.

The last ten years have been similar to the late 19th century. And now it seems that any recovery from the pandemic slump will be drawn out and also deliver an expansion that is below the previous trend for years to come. It will be another leg in the long depression we have experienced for the last ten years.

The link in this article to the Bloomberg article on JP Morgan estimating a loss of 5 Trillion is broken. This is the full link https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-04-08/world-economy-faces-5-trillion-hit-that-is-like-losing-japan

Thanks Mohamed. I’ll correct

I don’t understand why MMTers are celebrating: it was the decision by the American Congress to print money that triggered the wave of unemployment in the USA.

The situation was pretty much clear: USA’s recent wave of low unemployment was sustained by very low, intermittent jobs (“gig”). When the Congress announced it would be giving out USD 1,200 for everyone who lost their job, those people simply accessed the social security website and filed the unemployed form. After all, USD 1,200 was more than they would earn if they kept working.

Printing money, therefore, dismantled the American social structure and fuelled unemployment.

MMT is already dead in the water. I cannot even believe there are people who call it a “theory” – this is an insult to the great Western thinkers of illuminism, Marx included.

“I don’t understand why MMTers are celebrating: it was the decision by the American Congress to print money that triggered the wave of unemployment in the USA.

The situation was pretty much clear: USA’s recent wave of low unemployment was sustained by very low, intermittent jobs (“gig”). When the Congress announced it would be giving out USD 1,200 for everyone who lost their job, those people simply accessed the social security website and filed the unemployed form. After all, USD 1,200 was more than they would earn if they kept working.”

Total, incoherent, ignorant, anti-Marxist nonsense. Facts: 1) Congress does not print money; 2) employees who quit their jobs are, in general, ineligible for unemployment 3) very little of the $1200 has reached anybody and is unlikely to for several more weeks; the layoffs have been going on for a month.

I would ask where VK gets his/her information, but I’m sure he/she just makes stuff up.

More: the $1200 is a one-off, and nobody quits their job for a one-off when that disqualifies him/her from unemployment. The $1200 grant was passed in the last week of March, by which time the layoffs were well underway having begun March 11, fully two weeks before the legislation. Payrolls dropped by 701,000 in March, not because employees quit, but because they were laid off. They were laid off in the oil sector, as prices collapsed. They were laid off in the automobile sector. They were laid off in the food service, travel and leisure, sectors.

My information checks out. We don’t need to get legal here: the Congress can de facto print money through budgets and packages.

But that’s only true for the US Congress, of course, as the USA issues the universal fiat currency (USD).

The chronology checks out. The first wave of 6 million unemployed came out right after the first relief package was approved. The SS website crashed, so many people couldn’t fill the form within the week. So a second wave – 3 million – came the next week.

What appeared to be an isolated event became a house of cards, as another wave of 6.6 million came the next week after that.

The explanation is very simple: American growth post-2008 was built upon a new class of workers – the gig workers – who worked intermittently or and/or below subsistence wages. They were not technically unemployed because the BEA changed its methodology during the Bill Clinton era, but were on the edge.

When it became clear the lockdown wouldn’t end soon, those hordes of subemployed rushed to the SS in order to get that USD 1,200.00 check. Yes, they later discovered it was a scam (they would receive it only in June/July), but the opportunity cost is low (you just need to fill a form on the internet).

Those geniuses of MMT didn’t know, but the reality is that people don’t work because they want to, they work because they have to. Once they realized they would get paid without working, they seized the opportunity.

Post-2008 USA economy is built upon hyperexploitation of labor. This means that wages under subsistence levels are essential to its social cohesion. Once MMT was applied, this social contract was broken, and the USA begun to unravel.

I’m not one to make these kind of bets, but I’m tempted to call it here that the MMTers may well enter in History as the American Gorbachevs.

you’re an idiot

To expand on my earlier remark–

Fun Fact: the $1200 stipend has nothing to do with employment status. All that’s required is that you have a social security number or filed taxes with the US government in a prior year.

So the notion of workers quitting jobs so they’d be eligible for a one-off $1200 payment is……….idiotic, and just another iteration of the right-wing baloney that government subsidies, welfare payments, or even unemployment benefits, make workers lazy, encourage indolence.

VK asks us to believe that Macy’s isn’t laying off 130,000 people– rather those people quit so they could get a $1200 stipend for which they were already eligible.

All those restaurant workers, Uber drivers, truckers, theater employees, retail workers, they just up and quit their jobs en masse to become part of the army of the unemployed for the grand sum of $1200 dollars.

Idiotic.

Yes, we could see a resurgence of CPI type inflation in the face of the supply shock. We already see it in India with a galloping inflation emerging in food prices:

https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/food-prices-surge-3-times-as-supply-chain-takes-a-hit/story-QRqfvQpEnlJOdbwWzsCl4N.html

On a related topic, might this be the event that resets your Kondratiev cycle? I’ve never been a “believer” in Kondratiev cycles as theory, regarding them as empirical evidence of something larger than economy, namely that the fate of capital accumulation is inextricably bound up with the fates of capitalist (and non-capitalist) social formations. Otherwise I follow Leon Trotsky’s critique made in 1923:

https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1923/04/capdevel.htm

In my understanding, then, a “cycle reset” would require not only the quantitative realization of a mass purge of “zombie” and otherwise weak capitals, clearing the deck for another cycle of mass concentration/centralization of capital, but also a *qualitative* restructuration of the *regime of accumulation*. US capitalism, for example, would make a decisive and more or less “permanent” shift from what I call New Deal “labor liberalism” that sought to keep wage labor tied to the labor market (and the consumer market generally, hence “consumerism”), to a more social-democratic short-circuiting of labor market dependence, and forms of social provisioning no longer entirely dictated by the law of value (see Ben Fine on “systems of provision” in “World of Consumption”).

This second requirement becomes ever more important, by leaps and bounds, as “restarted” accumulation on the basis of a fully restored RoP (not quite achieved in the 1990’s, IMO) becomes a vastly more complex social problem as society itself becomes a qualitatively more complex organism in each succeeding historical era of accumulation (because if the second requirement was not met, there would either be societal collapse or the replacement of capitalism tout court).

This would define an historical arc of capitalism: as the social organism leaps in complexity with each mass structural reform, the capacity of typically capitalist social relations, including its typical political, cultural and ideological relations, to surmount “the next general crisis” becomes weaker. Each leap must be multiples larger than its predecessors. Hence the probabilities for a successful next leap fall.

In the final analysis that outcome will be a determinate of politics, not economics.

I don’t think inflation is in the cards at all, not with oil at $20/barrel; auto sales declining well before the pandemic.. it’s just not going to happen.

Depends on how the supply crash goes. The pandemic is the equivalent of a massive, if temporary, destruction of productive capital. And for weaker capitals, it will be RIP, not temporary.

It is not only the development and technological invention (which is good to point out, it has always accompanied each new Kondratieff cycle) the impediment that the capitalist regime has today to initiate a new long wave of expansion; there is another element, perhaps the most important, and that is that «… although the internal logic of the laws of capitalist movement can explain the cumulative nature of each long wave, once started, and although it can also explain the transition of an expansive long wave to a long wave of stagnation, it cannot explain the passage from the last to the first »; that is to say, there is no automatic internal logic of capitalism that can lead from a long depressive wave to an expansive one (which is what capitalism needs and yearns for today), since exogenous factors are indispensable for this to happen.

I get the argument of those who say these COVID depression is not a big deal: all things being equal, this is just a slow down in turn over time. There is no overproduction because the circuit is just slower. As soon as the pandemic is over, it will resume its speed.

I think the decline in growth rates or in global trade are not the main problems after the shutdown. For us “consumers” it is importand first of all whether the decline in production also affects everyday essentials or not.

And it is important for all companies how their debt develops.

Most of the companies were already heavily indebted before the crisis and will not be saved by any state aid.

https://marx-forum.de/Forum/index.php?thread/1011-was-kommt-nach-dem-shutdown-schuldenerlass-oder-steuertropfen-auf-den-gl%C3%BChenden/&postID=5446#post5446

Wal Buchenberg, Hannover

Isn’t it a case that once China fully industrialised a new collapse would occur as the conditions for industrialisation aren’t the same as the conditions for when industrialisation has occurred?

The new world cannot but be for a form of UBI and automation if the system is able to implement the changes prior to its overthrow?

As the West used cheap labour in the form of mass migration to remain afloat and China its low economic base. Now both have found an equilibrium a crash could not but occur and a breakdown is on the cards with Japan announcing withdrawal from China and the AngloAmericans to sue China for the Lockdown…. so trade wars are back?

Other than that, though, everything’s fine.

Interesting. Doesn’t deal with the fact that there will be massive investment — not to the benefit of working people — in further concentration and centralization of capital and in absorption of “dead labor” into capital through further development of robotics. They are already introducing robots into cleaning and sanitizing and other operations in hospitals and medical facilities. The Army Tank Division is leading (inter)national effort for autonomous vehicles in order to develop fleets of self-driving trucks that can operate in tandem (as well, of course, as self-driving tanks to replace the need for unreliable and potentially rebellious human troops). Amazon et al are already introducing robots into warehouses. The selling point of “untouched by human hands” will accelerate this, as will the resistance that is growing among warehouse workers, grocery workers, health care workers, factory workers and transit/transport workers (among others). That will just deepen further the insurmountable and irreconcilable contradictions of capital and capitalism.

The IMF has just published in their blog this article The Great Lockdown: Worst Economic Downturn Since the Great Depression by Gita Gopinath, “the Economic Counsellor and Director of the Research Department at the International Monetary Fund (IMF). She is on leave of public service from Harvard University’s Economics department where she is the John Zwaanstra Professor of International Studies and of Economics.”

Mutual recognition that money means wealth has to exist for fiat money to maintain its exchange-value. With gold and silver, it’s different. They both embody socially necessary labour time. But, there just isn’t enough gold and silver in the world to use as the money commodity anymore because labour is so very productive of wealth and so many natural resources have been discovered and are owned for sale. So, the mutual recognition that say, $1,700 paper U.S. dollars are worth the socially necessary labour time embodied in an ounce of gold will crumble in the minds of the faithful as more and more money is printed a la Modern Monetary Theory, just as the full faith and credit of God has been withering in the minds of humans over the centuries as the demystification of the Universe though scientific discovery has developed.

There are many people who are capable marxist economist’s including michael roberts himself who ought to delve deeper into modern money theory before they dismiss it so quickly.try william mitchell’s blog for starters or the works of l. Randall wray,william mosler and stephanie kelton.the critiques at this web site are very weak characterisations of that body of work.there are no good reasons for scholars of marx to savage that body of knowledge so flippantly imho.

Prediction: government will hand out money to the largest companies who will buy up the smaller, called consolidation. We saw this last time when the large banks became more powerful than before the Great Recession. Labor will be scarce, wages will drop, organized labor will take a hit. This is the likely game plan of this administration. Inequality will be greater. FDR is not the president, there will be no WPA. I admire the writing of Philip Harvey who argues that the WPA had a fuller effect than generic spending that increases aggregate demand.

A summary says, “the WPA (the “New Deal strategy”) is best understood as an effort to secure what the New Dealers came to regard as a human rights entitlement—the right to work—rather than as an economic policy designed to promote the economy’s recovery from the Great Depression. The paper goes on to argue, though, that in fashioning a policy to secure the right to work, the New Dealers unknowingly developed a strategy for delivering a Keynesian fiscal stimulus that is markedly superior to other anti-recession strategies.” — from “Learning from the New Deal”.

This crisis or disruption is an opportunity, but I don’t think the public is intelligently prepared to make the most of it. The blog consistently publishes the best summations of the situation. Helicopter money in the right places makes total sense. In the wrong places it doesn’t.

The New Deal was no deal for labor. Ir was a deal with Anglo American capital that promised WAR, the destruction of foreign capital, the US foreign investment and super-exploitation of labor in defeated and subsumed foes, and meanwhile the control of US unions, cap on wages and forced savings. This new deal created US military and financial global hegemony…until now. War seems still the only right or left wing Deal for capitalist reproduction. They deal with a packed deck and we shouldn’t play their game.

I should add, that if it were possible to add to such a “human rights” “deal” a drastic reduction in US military spending (by at least half) and the dismantling of US foreign bases–i.e. negating the “deal’s” necessary war component–we would have a deal that would be a totally different kind to deal from that of the the Democrats under Roosevelt. Which is to say, no “deal” at all, but revolutionary struggle and change.

Michael writes:

“The assumption of the radical post-Keynesian/MMT boys and girls is that if governments spend and spend, it will lead to households spending more and capitalist investing more. Thus, full employment can be restored without any change in the social structure of an economy (ie capitalism). Under MMT, the banks would remain in place; the big companies, the FAANGs would remain untouched; the stock market would roll on. Capitalism would be fixed with the help of the state, financed by the magic money tree (MMT).”

You still don’t get MMT. It’s not about governments “spend and spend”; it IS about government using its currency issuing capacity as required in any given situation, eg, in this pandemic, to pay for the food and accommodation of laid off workers.

Households won’t be spending more, in fact most nonessential economic activity is closed down. Even wealthy households can’t spend.

But the fact is in normal times, free markets never create full above poverty employment. That’s where the countercyclical MMT JG comes in: a guaranteed above poverty income that by its nature won’t generate excess demand, but will prevent a fall into prolonged poverty.

And MMT recognises that much of the vast OTC and derivates trading financial casino is fraudulent and a parasite on the real economy, so MMT certainly would change the face of capitalism.

Nevertheless, how would YOU deal with this pandemic, when people are FOBIDDEN to work? See how easily MMT can deal with it, by ensuring everyone eats and is housed – without governments being forced to take on crippling levels of debt that must be repaid with interest to rich bondholders.

That’s why MMT is being particularly noticed now……because it offers the ONLY way to avoid economic and social collapse, and avoid debt obligations that will crush future generations for decades

Neil – where does MMT advocate any change in social structure ie public ownership of the banks and large multi-nationals to plan investment and employment, as the Communist Manifesto did? If it does not, then, in my humble view, it will not stop recurring crises in capitalist production or reduce inequality of wealth and income by any significant amount. If fossil fuel energy companies are not to be touched, how will climate change be stopped? If you look at this way, MMT is not very radical, even if it stops the worst levels of unemployment and poverty. It’s a backstop to capitalism not an alternative.

Michael, in MMT “public ownership of banks” is implied, in the use of the currency issuing capacity of the state (whether private banks continue to exist or not); and in fact MMT would nationalize (globalize) the entire fossil fuel industry (as said by BIS at Davos: “central banks should buy the fossil industry”….because they have unlimited currency-issuance capacity) to transition the globe to a green economy.

Hence professor Mitchell sees a massive expansion of the public sector, and elimination of the mutli-national energy companies, to deal with climate change.

Here is the problem. For MMT to work it has to be inflationary. If we take the scissors effect of a 30% industrial contraction intersecting with a 15% stimulus (as a share of GDP) it has to be inflationary when a sizeable amount of that money bearing Trump’s name enters into the pockets of the bottom 80% who have no choice but to spend it. So while you may be right about the debt issue, the price paid will be a sharp rise in the CPI because MMT necessarily devalues the value of money.

Great two posts by you recently

Thank you. Social unrest is breaking out on many continents. Developing our theory and programme is more important than ever.

There’s not going to be inflation.

ucanbpolitical wrote:. “For MMT to work it has to be inflationary”.

Not true. Take this pandemic. The currency issuing government can pay for food and accommodation (and internet) of unemployed workers, *without borrowing the money*, and without causing inflation, because the food production and accommodation already exist and will be ongoing, while non-essential production and trade is forced into ‘hibernation’.

But in normal times, the limit to currency issuance, whether in the public sector and/or money creation in private banks, is the productive capacity of the economy.

IOW, there will be no inflation as long as there are goods and services available to be purchased. eg, if the economy’s productive capacity increases as a result of an increase in the money supply (via smarter machines etc), new wages can be spent on the increased production without raising prices.

It will be patchy. Durable prices may fall but non-durables will rise. Coffee up 15% this month. It highlights food is the issue.

”But in normal times, the limit to currency issuance, whether in the public sector and/or money creation in private banks, is the productive capacity of the economy.”

Surely this is true in abnormal times as well?

”IOW, there will be no inflation as long as there are goods and services available to be purchased. eg, if the economy’s productive capacity increases as a result of an increase in the money supply (via smarter machines etc), new wages can be spent on the increased production without raising prices.”

”as a result of”? Frankly, I cannot comprehend this. How can an economy’s productive capacity increase purely as a result of printing money. Sure didn’t happen in Weimar Germany!

“IOW, there will be no inflation as long as there are goods and services available to be purchased”. But that is precisely the problem!

Money supply in a pandemic is required only for essential goods and services. Additional money supply is also required to maintain workers formerly producing nonessential goods and services on payrolls. Nothing changes price-wise for essential commodities, as both “essential” and “non-essential” consume these as before.

However wages prior to the pandemic were also exchanged against “non-essential” but now, largely non-existent, current consumer commodity production with few online substitutes. It would appear that MMT, to avoid a cpi inflation, would have to *reduce* nominal wages across the board to that required for essentials. And this would be an actual reduction of real wages too, compared to before the deluge.

Otherwise, inflation in 3 areas:

– CPI essentials;

– Online substitute “non-essentials” (Amazon, EBay, Netflix. etc)

– Housing rents! Rent is a form of tribute and is exchanged against no commodity production. With tenants afraid to move, landlords can rack rents under pandemic MMT.

What Anticapitalist has in mind is the present case of the USA, where the “plan” is to reduce wages the old fashioned way, through mass unemployment rather than maintain wages thru payroll support. Yes, a wage collapse will throttle inflation. But the USA is not the MMT case at all. Nevertheless it is impossible to see how MMT avoids inflation in the above 3 cases without wage reductions, however “temporary” (and we are talking about ~1 year possibly).

If MMT is what you’re describing, then it is utopic.

By the time a central government has such capacity of governance, we’re already well into a stage of planned economy. Money would self-annihilate.

Vk says “Money would self annihilate”.

Certainly the time might come when the productive capacity of post industrial AI and IT economies profoundly changes the relationship of individual consumers to money. Marx’s vision of “from each according to ability, to each according to need” would certainly apply, within an environment of special recognition for special creativity (which I think the Marxian concept lacks?).

But that’s away off yet; in lieu of a socialist revolution, we will need to use the currency issuing capacity of government to prevent the economic and social collapse that we all agree is looming, under the current neoliberal monetary orthodoxy..

It would seem that mmters (and even much of the “left”) at imperial centers tacitly accept as given the obscene human, environmental, and moral costs of war and empire. Would even the thought of such a fabulously selfish, niggardly bourgeois, notion as mmt jg be possible without the psychedelic effects of the US, imperial dollar? Besides, it seem clear that the rest of the world can’t, and won’t, pay for it.

mandm: there are sufficient RESOURCES in the world to supply houses, clothing, food etc (the essentials) for all, (except perhaps in certain overpopulated states which might need assistance from an international institution) to establish universal above poverty participation by means of currency issuance. Money per se is not the limiting factor. See my other posts above.

Now I agree countries need to abandon the obsolete concept of absolute national sovereignty, and sign up to an international rules based system in which war is finally de-legitimised. But we can walk and chew gum at the same time.

“There are sufficient RESOURCES in the. world to supply houses, clothing, food, etc. (the essentials) for all…”

Neil, this assertion slips so insouciantly off your tongue, because, while walking and chewing gum at the same time, you chose to ignore (in your post-industrial material brain) the actual, continuing, criminal imperial wars and threat of same that have created and continue to create the obscene global social relation that makes possible the super-exploitation of 80 percent of the world’s industrial work force who (when not being bombed) actually produce those “sufficient RESOURCES” (including ventilators and our computers). Enjoy.

”You still don’t get MMT.” Me neither! What is the value of this money? How much labour will it command? For example, let us say Britain imports 50% of its food. Of any £1000 citizens spend £250 on imported food of a value of £250 expressed in a price of £250. Now suppose because of ecological and climatic disasters ( just up the road) the cost of production of such foods doubles and their value is now £500. Will the Government just issue additional currency to the ‘value’ of £250 per person? Will this additional £250 be acceptable to the foreign producers? What increase in the value of British output would this extra £ 250 allow the foreign producers to command with this money? Am I intellectually challenged or does the sad tale of King Midas not apply?

jlowrie writes: “What is the value of this money”.

Answer: the value which occurs with continuous, *sustainable* utilisation of available resources and real full above poverty employment. Currency issuance is limited by that outcome, to avoid inflation.

Even this pandemic proves the concept: with a large quantity of labour forcefully idled, money maintains its value as the currency is issued by the central government to replace lost wages of laid off workers, while non-essential consumption is much reduced.

How simple is this?

1. Government faces real resource constraints.

2. Government does not face purely financial constraints.

3. Government can always repay future debt obligations denominated in its own currency, provided the productive capacity of the economy is maintained.

Note: money is a measuring token – a government IUO – that is theoretically unlimited, like the ‘points’ handed out in a football game. . There is no limit to the points that can be scored by the opposing sides….. provided the inflation limit (real ‘value’ of the points) is observed, which has been addressed above.

Now, if a country imports 50% of its food, and the price of imported food doubles, then indeed the government cannot simply issue the currency to purchase this imported food without devaluing the currency, because the *resource* constraint noted above now applies.

One course of action would be to increase self-sufficiency in food, or accept a devaluation of the currency.

You use a definition of value based on the continuous motion of the economy, yet another based on a government edict. You resolve this by mentioning money is a “measuring token”, which confirms you’re using the latter definition (fiat), which is consistent with MMT.

But MMT is not about defining value in any objective sense; it’s about trying to re-frame how to think about the inflationary effects of issuing currency prior to production. This is nothing new fundamentally, just another way of ignoring the social relations underlying what a society ultimately decides to produce and how distribute. The government’s ability to tax the currency, is itself, a product of prior production determined by social relations — objectively measured by labor-time comprised of available energy and resources.

If MMT wants to contribute a theory of value, it should scheme a currency based on the currently existing productive forces and the rate of depletion/improvement of its ecological foundations, “pricing in” future resource constraints. This would immediately bankrupt capitalism today, of course. Yet, even in that scenario, there is still a social process that ultimately decided what to produce, which raises the question of why there needs to be monetary layer at all.

Neil, Thank you for your reply. You say,”the value that occurs with continuous sustainable utilisation of available resources” But given the capitalist mode of production such utilisation depends on its being able to engender a profit. Anyway, in view of the impending cataclysm I feel we need to be arguing for full-blown socialism. We should not be drawn into wasting time on debating mere reforms, however necessary in the immediate, short term.

Paul Cockshott’s wonderful lecture :

Europe faces climatic changes of a scale not seen since the end of the ice age. What impact will this have on society and how can we plan to deal with it?

YOUTUBE.COM

”The impending catastrophe and how to plan for it ( with cleaned audio)”

”In the depression of 1873-97 (that’s over two decades)”,

A critic. Off Topic (or not). That fact of the depression of 1873-1897 (true, demonstrable and repeated data in this same blog and in other authors and sources) is 100% contradicted with its dates of Kondratiev cycles in the final part of the 19th and 20th centuries. If there was such a ‘Long Depression’ at the end of the XIX century, in that period there could not have been a period of upward phase (spring and summer) of a Krondatiev cycle. It is impossible. That is not a period of growth but one of decrease, a depression that widens with the financial collapse of 1907-8. On the other hand, since 1914 (or 1917) it was not a period of depression either, except for the crash of the year 29. A financial crack with a focus spatially distant (USA) from the focus of the momentum of the Kondratiev cycle (Russia) and crisis that does not deny the growth of the period after 1917 in the World-System.

A suggestion for cycle dates that fits the correct growth and depression data is as follows. 2nd cycle Kondratiev (in the 19th century): Its bullish phase began in 1848. Start of decrease phase in 1.875. End of the 2nd cycle in 1.917. /// 3rd Cycle Kondratiev (in the XX and XXI centuries): Start: 1.917. End of the bullish phase and start of the decrease: end of the 70s. End of the complete cycle: approx. 2,050.

This new corrected temporal development of the Kondratiev cycles fully matches the ULTIMATE correct cause of these cycles. Ultimate cause that is not that of capital accumulation derived from investments in infrastructure (according to Kondratiev) or derived from technological innovations (other authors) but that the ultimate cause is a political shock: revolutions.

On the other hand, I fully subscribe to his thesis that the Pandemic (like the crisis of 2008) only exacerbated the decline in previous growth (except China, perhaps, if it maintains its% of state participation). That the recovery will be L-shaped in 2,3,4 years, but that it will not reach the previous growth that is already declining. And that the MMT and Kenynes will not avoid, even if they temporarily soften their damages, monopolistic concentration in the markets with the corresponding extreme inequality (small closed companies, unemployment, etc.).

Regards

‘’ But that the ultimate cause is a political shock: revolutions ’’

Are the Kondratiev cycles revolutionary cycles? Are they the revolutionary cycles of capitalism? An extension and justification.

Short argument.-

Why is the intensive accumulation of capital in infrastructure (according to Kondratiev) or in technological innovations (other authors) NOT the ultimate cause of the Kondratiev cycles (cycles which I also call revolutionary cycles and / or cycles of class struggles) ? The usual criticism, and to which I subscribe, is that companies, of a sector or of the entire country or countries, do not decide their investments at the same time, simultaneously. Conversely, companies invest according to their date of incorporation and according to the different useful lives of their assets and decide on new investments or renewal of the current ones at DIFFERENT moments of each other. However, Kondratiev says he detects (and he has strong evidence empirical of this) that on certain dates there have been large accumulations of simultaneous investments, especially in infrastructure, in different sectors and countries. Where does it come from, what is the cause of those general SIMULTANEOUS investments? Due to the aforementioned, this increase can only come from a simultaneous creation of companies, from an explosion in the creation of means of production. Neither logic nor economic evidence allows any other cause. And these explosive business creations are autonomous or have some cause behind them? In some specific sectors (digital, computing in the last decades and other sectors in previous centuries such as, railways, steam engines, etc.) there have been notable increases in the constitution of companies and their investments, awaiting the new profits of technological innovations of each sector. But these increases in companies were never in the majority of sectors, nor in a large group of countries AT THE SAME TIME. What can produce these general and simultaneous creative explosions of companies? I know, we all know, on what dates Kondratiev detects these massive capital investments. And knowing it, and playing with an advantage, I know the answer. The dates of these massive reversals are around and after 1,789 and 1,848, the two dates in which the first nineteenth-century Kondratiev cycles begin. And what happened on those dates that could enable the massive creation of companies and their investments? Only one phenomenon is possible: political revolutions. Did revolutions happen on those dates? Yes, they did. Are the 2 construction revolutions of Capitalism: The French Rev. and the European Liberal Revolutions? That is, they are the 2 main revolutions (in addition to the English Gloriosa) that allowed the bourgeoisie to assault the ownership of the means of production, which until then and for centuries were the exclusive and privileged property of the Feudal Nobility.

Evidence.

1.- The French Revolution promulgates 3 laws that allow free enterprise previously prohibited to any citizen.

2.- In the Glorious Revolution, the subsequent explosion of corporations is documented.

3.- In the following text, from the excellent work of History of Insurance in Spain, directed by the economist Grabiel Tortella for the Spanish insurer Mapfre, this statement is appreciated, in addition to others and abundant evidence, about the passage of companies Individual insurers to corporations and / or corporations in the insurance sector, especially in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries:

a) ‘The most significant change in the insurance market in the Modern Age was introduced with the appearance of specialized companies. Traditional historiography has linked this transformation to the spread of share-based insurance companies throughout most of Europe, in the case of England at the end of the 17th century and for the rest of the continent in the 18th century (Halperin, 1947) ”

In my opinion, it is very likely that in the majority of texts of History of products and sectors the same increase of mercantile companies is detected on those same dates and periods. And that it is detected in the National Statistical Yearbooks.

. This evidence provided is, surely, not very conclusive, but not because that evidence does not exist (in fact I think that it is relatively easy to find the explosion or not in the creation of companies on certain dates, business creation that is the ultimate cause of the Kondratiev cycles), but because my capacity as a macro-economist goes as far as it goes. It is a non-professional capacity and only an amateur type.

A greeting

One last consideration on Kondratiev cycles and revolutions.

In the 19th century, the bourgeois liberal revolutions created the explosions in the constitution of companies in 1,789 and 1,948 that gave rise to a simultaneous and massive accumulation of capital and, for this very reason, these revolutions should be considered the ultimate cause of

a) The increase in annual growth. From 0.5% per year before the 19th century, to 1.5% in western countries according to Agnus Maddison. It is the change of productive scale of Capitalism vs. Feudalism. And it is the expansion of the number of owners of the means of production, and

b) the Industrial Revolutions of the century.

In the 20th century. Yes, it is true that in the Golden Age, from the end of the 2nd GM, there is an increase in investment (state and private) and growth and that some authors place the beginning of a Kondratiev cycle at that time. But by doing this, what happened in Eastern Europe and since the 2nd decade of the century is being omitted incorrectly. We are omitting the Russian Revolution and its (colossal) effects. First, with effects in all the countries of the socialist area, promoting the State as the main agent of the economy and investment. With a strong increase in investment and annual growth. SINCE THE 2ND DECADE OF THE XX. It is the real socialist state, a state not yet in workers’ democracy, but that did mean an expansion in the ownership of companies. From private property to social property. Another brutal change of productive scale such as the one that Capitalism supposed in the XIX century, that catapults the socialist growth including China. State as an economic agent that spreads to Keynesianism and Western economies. They are the economic impulses and their spread of Ragnar Frisch. The closer to the focus of the impulse, close in space and close in time, the stronger its effects. From Nordic quasi-socialism to the few and weak welfare states of southern Europe.

Why should we think Dean Baker is a leftist economist? The last I looked his big thing is that government monopoly leads to rent seeking and that’s the cause of all our troubles. If I remember correctly, he doesn’t even pay attention to the role of real estate in the banking system. (Michael Hudson does?) So Baker seems to claim the problem with healthcare is overpaid doctors, because medical licenses and drug patents. And so on, and so forth. In what sense is this approach left-wing?

jlowrie writes: “How can an economy’s productive capacity increase purely as a result of printing money. Sure didn’t happen in Weimar Germany!”

It can’t, so my original statement was poorly constructed. Let’s try this:

” if an economy’s productive capacity increases (eg via smarter machines etc), an increase in the money supply can be absorbed into the economy without raising prices.”

In the Weimar Republic the opposite occurred – factories and machines were removed by France, as war reparations.

Well, that holds water, but MMT won’t float in it.

The “Economist” incorrectly reports today: “Germany is allowing large shops to trade …” – that would make sense from a medical point of view, because the distance rules could be better adhered to in larger stores.

It is a mere clientele policy that the federal government instead allows smaller shops with sales areas under 800 square meters to resume trading.

It is the exit from health policy back into economic policy.

Wal Buchenberg, Hannover

Facing the new data, is it likely that the post-pandemic slump leads to the long depression’s end? Can we expect a new phase of capitalist growth after this great slump?

Important question on which I plan to write once I have clarified my thoughts

A couple of comrades and I have translated this blog post into Serbian, available here: https://marks21.info/postpandemijski-pad-privrede/?fbclid=IwAR2HMYc_zAZd7DFXXKkRBGPozPRbIPenm2NWFKBAORHaQTspmlL1qtpiPZA

Great alek. I shall post it on my Facebook