All our wealth has been stolen by big finance and in doing so big finance has brought our economy to its knees. So we must save ourselves from big finance. That is the shorthand message of a new book, Stolen – how to save the world from financialisation, by Grace Blakeley.

Grace Blakeley is a rising star in the firmament of the radical left-wing of the British labour movement. Blakeley got a degree in politics, philosophy and economics (PPE) at Oxford University and did a masters degree there in African studies. Then Blakeley was a researcher at the Institute of Public Policy Research (IIPPE), a left-wing ‘think tank’, and has now become the economics correspondent of the leftist New Statesman journal. Blakeley is a regular commentator and ‘soundbite’ supporter for left-wing ideas on various broadcasting media in Britain. Her profile and popularity have taken her book, published this week, straight into the top 50 of all books on Amazon.

Stolen: how to save the world from financialisation is an ambitious account of the contradictions and failures of postwar capitalism, or more exactly Anglo-American capitalism (because European or Asian capitalism is hardly mentioned and the periphery of the world economy is covered only in passing). The book aims to explain how and why capitalism has turned into a thieving model of ‘financialisation’ benefiting the few while destroying (stealing?) growth, employment and incomes from the many.

Stolen leads the reader through the various periods of Anglo-American capitalist development from 1945 to the Great Recession of 2008-9 and beyond. And it finishes with some policy proposals to end the thievery with a new (post-financialisation) economic model that will benefit working people. This is compelling stuff. But is Blakeley’s account of the nature of modern Anglo-American capitalism and on the causes of recurring crises in capitalist production correct?

Just take the title of Blakeley’s book: “Stolen”. It’s a catchy title for a book. But it implies that the owners of capital, specifically finance capital, are thieves. They have ‘stolen’ the wealth produced by others; or they have ‘extracted’ wealth from those who created it. This is profits without exploitation. Indeed, profit now comes merely from thieving from others.

Marx called this ‘profit of alienation’. For Marx it is achieved by the transfer of existing wealth (value) created in the process of capitalist accumulation and production. But value is not created by this financial thievery. For Marx, profits, or surplus value as Marx called it, is only created through the exploitation of labour in the production of commodities (both things and services). Workers’ wealth is not ‘stolen’, nor is the wealth they create. Under capitalism, workers get a wage from employers for the hours they work, as negotiated. But they produce more in value in the time they work than in the value (measured in labour time) that they receive in wages. So capitalists obtain a surplus-value from the sale of the commodities produced by the workers which they appropriate as the owners of capital. This is not thievery, but exploitation. (See my book, Marx 200, for a fuller explanation).

Does it matter whether it is theft or exploitation? Well, Marx thought so. He argued fiercely against the idea of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, the most popular socialist of his day that ‘property is theft’. To say that, argued Marx, was to fail to see the real way in which the wealth created by the many and how it ends up in the hands of the few. Thus it was not a question of ending thievery but ending capitalism.

In Stolen, Blakeley ignores this most important scientific discovery (as Engels put it), namely surplus value. Instead Blakeley completely swallows the views of the modern Proudhonists like Costas Lapavitsas, David Harvey and others like Bryan and Rafferty who dismiss Marx’s view that profit comes from the exploitation of labour. For them, that is old hat. Now modern capitalism is now ‘financialised capitalism’ that gets its wealth from stealing or the extraction of ‘rents’ from everybody, not from exploitation of labour. This leads Blakeley at one point to accept the false analysis of Thomas Piketty that the returns to capital will inexorably rise through this process – when the evidence is that returns to capital have been inexorably falling – see my critique of Piketty here.

But these ‘modern’ arguments are just as false as Proudhon’s. Lapavitsas has been critiqued well by British Marxist Tony Norfield; I have engaged David Harvey in debate on Marx’s value theory and Bryan and Rafferty have been found wanting by Greek Marxist, Stavros Mavroudeas. After you read these critiques, then you can ask yourself whether Marx’s law of value can be ignored in explaining the contradictions of modern capitalism.

Then there is the sub-title of Blakeley’s book: “how to save the world from financialisation’. ‘Financialisation’ as a category or term has become overwhelmingly popular among heterodox economics. The category originally came from mainstream economics, was taken up by some Marxists and promoted by post-Keynesian economists. Its purpose was to explain the contradictions within capitalism and its recurring crises with a theory that did not involve Marx’s law of value and law of profitability – both of which post-Keynesians reject or ignore (see my letter to MR).

Blakeley takes the definition of the term from Epstein, Krippner and Stockhammer and makes it the centre-piece of the book’s narrative (p11). As I outlined in a previous post, if the term means simply an increased role of the finance sector and a rise in its share of profits in the last 40 years, that is obviously true – at least in the US and the UK. But if it means the “emergence of a new economic model … and a deep structural change in how the (capitalist) economy) works” (Krippner), then that is a whole new ballgame.

As Stavros Mavroudeas puts it in his excellent new paper (393982858-QMUL-2018-Financialisation-London), the ‘financialisation hypothesis’ reckons that “money capital becomes totally independent from productive capital (as it can directly exploit labour through usury) and it remoulds the other fractions of capital according to its prerogatives.” And if “financial profits are not a subdivision of surplus-value then…the theory of surplus-value is, at least, marginalized. Consequently, profitability (the main differentiae specificae of Marxist economic analysis vis-à-vis Neoclassical and Keynesian Economics) loses its centrality and interest is autonomised from it (i.e. from profit – MR).”

And that is clearly how Blakeley sees it. Accepting this new model implies that finance capital is the enemy and not capitalism as a whole, ie excluding the productive (value-creating) sectors. Blakeley denies that interpretation in the book. Finance is not a separate layer of capital sitting on top of the productive sector. That’s because all capitalism is now ‘financialised!: “any analysis that sees financialization as a “perversion” of a purer, more productive form of capitalism fails to grasp the real context. What has emerged in the global economy in recent decades is a new model of capitalism, one that is far more integrated than simple dichotomies suggest.” According to Blakeley, “today’s corporations have become thoroughly financialised with some looking more like banks than productive enterprises”. Blakeley argues that “We aren’t witnessing the “rise of the rentiers” in this era; rather, all capitalists — industrial and not — have turned into rentiers…In fact, nonfinancial corporations are increasingly engaging in financial activities themselves in order to secure the highest possible returns.”

If this were true, and all value comes from interest and rent ‘extracted’ from everybody and not from exploitation, then it would really be making money out of nothing and Marx has been talking nonsense. However, the empirical evidence does not bear out the ‘financialisation’ thesis. Yes, since the 1980s, finance sector profits have risen as a share of total profits in many economies, although mainly in the US. But even at their peak (2006) the share of financial sector profits in total profits reached only 40% in the US. After the Great Recession, the share fell back sharply and now averages about 25%. And much of these profits have turned out to be ‘fictitious’, as Marx called it, based on gains from buying and selling of stocks and bonds (not on profits from production), which disappeared in the slump.

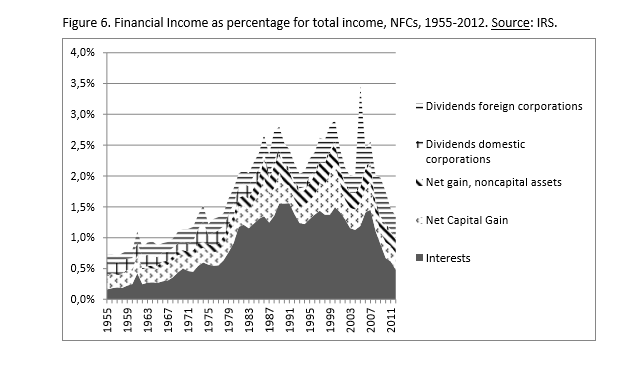

Also, the narrative that the productive sectors of the capitalist economy have turned into rentiers or bankers is just not borne out by the facts. Joel Rabinovich of the University of Paris has conducted a meticulous analysis of the argument that now non-financial companies get most of their profits from ‘extraction’ of interest, rent or capital gains and not from the exploitation of the workforces they employ. He found that: “contrary to the financial rentieralization hypothesis, financial income averages (just) 2.5% of total income since the ‘80s while net financial profit gets more negative as percentage of total profit for nonfinancial corporations. In terms of assets, some of the alleged financial assets actually reflect other activities in which nonfinancial corporations have been increasingly engaging: internationalization of production, activities refocusing and M&As.” Here is his graph below.

In other words, non-financial corporations like General Motors, Caterpillar, Amazon, Google, Microsoft, big tobacco and big pharma and so on still make their profits from selling commodities in the usual way. Profits from ‘financialisation’ are tiny as a share of total income. These companies are not ‘financialised’.

Blakely says that “financialization is a process that began in the 1980s with the removal of barriers to capital mobility”. Maybe so, but why did it begin in the 1980s and not before or later? Why did deregulation of the financial sector start then? Why did ‘neoliberalism’ emerge then? There is no answer from Blakeley, or the post-Keynesians. Blakeley points out that the post-war ‘social democratic model’ had failed, but she provides no explanation for this – except to suggest that capitalism could no longer “afford to continue to tolerate union demand for pay increases in the context of rising international competition and high inflation”.( p48). Blakeley hints at an answer: “competition from abroad began to erode profits”(p51). But that begs the question of why international competition now caused a problem when it had not before and why there was high inflation.

But Marxist economics can give an answer. It was the collapse in the profitability of capital in all the major capitalist economies. This is well documented by Marxists and mainstream studies alike. This blog has a host of posts on the subject and I have provided a clear analysis in my book, The Long Depression (not a best seller). The fall in profitability forced capitalism to look for counteracting forces: the weakening of the labour movement through slumps and anti-labour measures; privatisations etc and also a switch into investing in financial assets (what Marx called ‘fictitious capital’) to boost financial profits. All this was aimed at reversing the fall in the overall profitability of capital. It succeeded to a degree.

But Blakeley dismisses this explanation. It was not to do with the profitability of capital that crises regularly occur under capitalism and profitability had nothing to do with the Great Recession. Instead Blakeley slavishly follows the explanation of post-Keynesian analysists like Hyman Minsky and Michel Kalecki. Now I and others have spent a much ink on arguing that their analysis is incorrect as it leaves out the key driver of capitalist accumulation, profit and profitability. As a result, they cannot really explain crises.

Kalecki says that crises are caused by a lack of ‘effective demand’, Keynesian-style and although governments could overcome this lack of demand through fiscal and other interventions, they are blocked by the political resistance of the capitalists. You see, as Blakeley says, “Kalecki’s argument is that not that social democracy is economically unstable, but that it is politically unstable.” For Kalecki, crises caused by capitalists being politically unwilling to agree to reforms. So apparently, social democracy would work under capitalism if it was not for the stupidity of the capitalists!

Minsky was right that the financial sector is inherently unstable and the massive growth in debt in the last 40 years increases that vulnerability – Marx made that point 150 years ago in Capital. And in my blog, I have made the point in many posts that “debt matters”. But financial crashes do not always lead to slumps in production and investment. Indeed, there has been no financial crisis (bank busts, stock market crashes, house price collapse etc), that has led to a slump in capitalist production and investment unless there is also a crisis in the profitability of the productive sector of the capitalist economy. The latter is still decisive.

In a chapter of the book, World in Crisis, edited by G Carchedi and myself (unfortunately again it is not a best seller) Carchedi provides compelling empirical support for the link between the financial and productive sectors in capitalist crises. Carchedi: “Faced with falling profitability in the productive sphere, capital shifts from low profitability in the productive sectors to high profitability in the financial (i.e., unproductive) sectors. But profits in these sectors are fictitious; they exist only on the accounting books. They become real profits only when cashed in. When this happens, the profits available to the productive sectors shrink. The more capitals try to realize higher profit rates by moving to the unproductive sectors, the greater become the difficulties in the productive sectors. This countertendency—capital movement to the financial and speculative sectors and thus higher rates of profit in those sectors—cannot hold back the tendency, that is, the fall in the rate of profit in the productive sectors.”

What Carchedi finds is that:“Financial crises are due to the impossibility to repay debts, and they emerge when the percentage growth is falling both for financial and for real profits.“ Indeed, in 2000 and 2008, financial profits fall more than real profits for the first time. Carchedi concludes that: “The deterioration of the productive sector in pre-crisis years is thus the common cause of both financial and non-financial crises. If they have a common cause, it is immaterial whether one precedes the other or vice versa. The point is that the (deterioration of the) productive sector determines the (crises in the) financial sector.”

You may ask: does it matter if the inequalities and crises we experience under capitalism are caused by financialisation or by Marx’s laws of value and profitability? After all, we can all agree that the answer is to end the capitalist system, no? Well I think it does matter, because policy action flows from any theory of causes. If we accept financialisation as the cause of all our woes, does that mean that it is only finance that is the enemy of labour and working people and not the nice productive capitalists like Amazon who only exploit us at work? It should not, but it does. Take Minsky himself as an example. Minsky started off as a socialist but his own theory of financialisation in the 1980s led him to not to expose the failings of capitalism but to explain how an unstable capitalism could be ‘stabilised’.

Undoubtedly Blakeley is made of sterner stuff. Blakeley says that we must take on the bankers in the same degree of ruthlessness as Thatcher and Reagan took on the labour movement back in the neoliberal period starting in the 1980s. Blakeley says that “the Labour Party’s manifesto reads like a return to the post-war consensus…we cannot afford to be so defensive today. We must fight for something more radical…. because the capitalist model is running out of road. If we fail to replace it, there is no telling what destruction its collapse might bring.” (p229). That sounds like the roar of a lion of socialism. But when it comes to the actual policies to deal with the financiers, Blakeley becomes a mouse of social democracy.

First, Blakeley says “we must adopt a policy agenda that challenges the hegemony of financial capital, revoking its privileges and placing the powers of investment back under democratic control.” Now I have argued in many posts and at meetings of the labour movement in Britain that the only way to take democratic control is to bring into public ownership the big five banks that control 90% of lending and deposits in Britain. Regulation of these banks has not worked and won’t work.

Yet Blakeley ignores this option and instead calls for ‘constraining’ measures on the existing banks, while setting up a public retail bank or postal banks in competition along with a National Investment Bank. “Private finance must be properly constrained” (but not taken over), “using regulatory tools that are international adopted.” P285. At various places, Blakeley refers to Lenin. Perhaps Blakeley should remind herself what Lenin said about dealing with the banks. “The banks, as we know, are centres of modern economic life, the principal nerve centres of the whole capitalist economic system. To talk about “regulating economic life” and yet evade the question of the nationalisation of the banks means either betraying the most profound ignorance or deceiving the “common people” by florid words and grandiloquent promises with the deliberate intention of not fulfilling these promises.”

As for a National Investment Bank, a Labour manifesto pledge, it leaves the majority of investment decisions and resources in the hands of the capitalist financial sector. As I have shown before, the NIB would add only 1-2% of GDP in extra investment in the British economy, compared to the 15-20% on investment controlled by the capitalist sector. So ‘financialisation’ would not be curbed.

Blakeley’s other key proposal is a People’s Asset Manager (PAM), which would gradually buy up shares in the big multinationals, thus “socialising ownership across the whole economy” and then “pressurising companies” to support investments in socially useful projects. “As a public banking system emerges and grows alongside a People’s Asset manager, ownership will be steadily be transferred from the private sector to the public sector.” (p268) “in a bid to dissolve the distinction between capital and labour” (p267). So Blakeley’s aim is not to end the capitalist mode of production by taking over the major sectors of capitalist investment and production, but to dissolve gradually the ‘distinction’ between capital and labour.

This is the ultimate in utopian gradualism. Would capitalists stand by while their powers of control are gradually or steadily lost? An investment strike would ensue and any socialist government would be faced with the task of taking over completely. So why not spell out fully a programme for a democratically controlled publicly owned economy with a national plan for investment, production and employment?

Stolen aims to offer a radical analysis of the crises and contradictions of modern capitalism and policies that could end ‘financialisation’ and give control by the many over their economic futures. But because the analysis is faulty, the policies are also inadequate.

Well done, one of your best articles. The Feijoda must have really agreed with you.

Financialization is the popular political expression for leverage. Nothing more nothing less. Imagine a tributary of the Amazon if you will. Its headwaters is production and the water coursing down its length is part of the surplus value diverted into speculation both current and preserved. On its banks are to be found a species of pigs belonging to the capital gains breed. They have purchased a claim which allows them space on the banks to drink from the river. The more pigs who turn up the pricier the claim to buy space on the banks seven if it means they get smaller mouthfuls, because the water in the river does not necessarily change. But to these pigs it is the price of the claims that is more important rather than the water they are able to drink, which shows that some species of pigs are less intelligent than others. It may even be the case that the frenzy to get to the banks is of such an order that they do not even get near the river. This unusual phenomenon is called negative interest rates. So from drinking water as the prime motive, it is now the speculation in claims itself that has become the driver. But headwaters are seasonal, and this seasonality is called the industrial (business cycle). Now it is the case that the water has stopped flowing or is flowing more slowly. The more alert pigs notice this and turn around and head for the exist seeking to cash in their claims. Soon a stampede follows and many a pig is crushed heading for the exist.

What distinguishes Marxists from left reformists like Grace Blakely is that these reformists are mesmerised by the pigs and the melee on the banks of the river. The growth in the number of pigs dominates their thinking. Marxists on the other hand are focused on the river, where it originates from, why some of it is diverted into this speculative tributary and what regulates its flow. All that has really happened since the 1980s and the collapse in the rate of profit, is that more water has been diverted down this tributary attracting many more pigs. More pigs relative to the water means each claim now buys less water. This is bad for the likes of pension funds. They now pay much more for their claims to income than before but it is good for those who deal in claims. And thus while capital gains may have soared because of growing leverage it has come at a price, a lower income for every Dollar or Pound invested in a claim. The amount of value competed over has not necessarily changed.

In the end of course, as Michael has pointed out, the extend of financialization is exaggerated. Up to year ago, the $60 billion profit made by Apple eclipsed the $50 billion in bonuses paid to every banker in New York. Oh yes, one industrial corporation outboxed all the bankers. I will post the current rate of profit for China this weekend. I am waiting for Wall Street’s response to what looks like a significant drop in US retail which will be reported today. Like the US, China’s industrial rate of profit has fallen sharply, which creates the backdrop to this speculative orgy.

Thank you, Michael. That is a very, very stimulating discussion of the book. A few spelling and punctuation mistakes. Question: when you say 15/20 percent of investment is “controlled by the capitalist sector,” who is the biggest investor/controller then?

Excellent article and thanks for this. I’m not au fait with all of the references but the points you make are easily understandable. There is a small group of commentators who have made their way into the old media often as “token” left wing commentators. Usually somewhat telegenic and young, I can’t help think that the TV editors like this so as to portray criticism as coming from inexperienced “kids” who don’t have the experience to back up their strong opinions. There’s something in that. I suspect if they started using those with more miles on the clock, the interviewers and editors would come unstuck rapidly

We rarely see Prof Steve Keen for example on mainstream TV but when he is on, he usually has more than enough weaponry to hold his own.

While I suspect this book will add something to the debate, I can’t help thinking that it is aimed at the Twitter audience looking for some quick way to justify their views.

All this is great but I am afraid that it is modern marxist literature shortcomings that allow that neo-keynsian kind of reasoning to be so popular (aside other obvious reasons of course…).

I am particularly referring to modifications of the law of value when it comes to R&D and other intellectual labor, and to the world-wide market under the influence of imperialistic international relations.

For instance, I am looking forward to your criticism of Rotta’s work on the commodification of products of intellectual labor as well as on his empirical and theoretical work on productive and unproductive labor in US. Similarly, I have followed with great interest the debate with John Smith.

Regarding the first issue, products of intellectual labor (software, algorithms, chemical compositions, musical compositions, films etc) are not consumed through their use, i.e., they don’t ware out, it is only their much cheaper material container that might ware out, they are non-rival and non-inclusive, i.e., they can have infinite users at the same time etc This means that they can keep being sold as long as there is a demand for them, or, in other words, they can suffer only moral depreciation, either for lack of demand or because they become technologically obsolete, but no destruction of their use-value, and therefore of their value, depends on their use. Such commodities, or in general, commodities that contain a lot of intellectual labor, or in other words, their value mostly depends on the products of intellectual labor they contain, obtain a price that cannot be fully explained by the abstract labor time expended for their production, and therefore can easily lead to knowledge/technological rents (thanks also to the IP law). More and more industries fall under this rule, due to increasing automatisation.

If now someone asks, ok, where are these rents coming from?

The answer is from the producers of other commodities (products or services) that contain less of this kind of intellectual labor products. It happens that most of this low-technology labor has already been transferred to countries of lower working costs.

All in all, what we have of the new capitalism, or as I prefer to say, imperialism, is the increase of the exploitation of the working class (the net effect of transferring production where labor is cheaper, and exploitation probably also higher -due to higher unemployment and state oppression), what John Smith and Higginbottom call super-exploitation, together with a strong stratification of the working class between relatively expensive, specialised labor, mainly in the imperialist countries on the one hand, and cheap, relatively non-specialised labor in the so-called developing, exploited countries.

This is what happens to exploitation, just because you are right to say that value doesn’t come from nothing, and this is true also for increased value, which requires increased or super- exploitation.

But, how is this value distributed among the competing capitalists?

This is where rents play an important, with imperialist, monopolistic, fully concentrated capital of mainly the imperialist countries, which controls most of technology, …historically accumulated capital and ….the dollar, “extracts” value from the rest of the capitalists around the world. It is mainly, this “rest of world capitalists” that by not being able to compete via technological progress with the imperialist capital, has no other means to increase their profits, but to increase the exploitation of their workers…

I fully agree with you that it is increasing organic composition of capital and falling profit rate that leads to these historical developments of world capitalism, but I think that many “dogmatically orthodox” marxists spend a lot of time to refute Lapavitsas and the like, and much less time to explain the modern reality of the system, where, yes, rents play an important role.

And those rents play an important role exactly due to the development of capitalism itself, i.e., intellectual labor, as a highly social labor, automatisms, world expansion of capitalistic mode of production, concentration of capital to groups that are more powerful than many of the worlds states… These are developments that cry for a marxist explanation, which will have to modify, to some extend the law of value, exactly because they reach as deep as the capitalistic production itself.

A look at Marx’s Grundrisse speaks in favor that Marx had roughly anticipated such evolutions as INTERNAL to capital, not just as external determinations that appear at more concrete levels of description of the reality. I will leave aside the quite well circulated recently paragraph on scientific labor, automatisms etc, and I will insist a little bit on rents and state violence, which sound as pro-capitalistic exploitation methods:

”

Lenin’s concept of imperialism, as a transitional stage of capitalism corresponds with the dynamic analysis of capitalist development framed by Marx. In his rough draft of Capital, Marx summarised:

‘As long as capital is weak, it still relies on the crutches of the past modes of production, or of those that will pass with its rise. As soon as it feels strong, it throws away those crutches, and moves in accordance with its own laws. As soon as it begins to sense itself and become conscious of itself as a barrier to development, it seeks refuge in forms which, by restricting free competition, seem to make the rule of capital more perfect, but are at the same time heralds of its dissolution and of the dissolution of the mode of production resting on it.’ (Marx, 1973: 651)

Here the actual course of capitalist development, its refuge behind mercantilist tariff barriers, its emergence as free trade, and its retreat into monopoly and protection are pictured as the expression of capital’s own transition. Perceptively, Marx anticipates Lenin’s theme that capital will ‘take refuge in forms’ that are at odds with its own laws, such as monopoly, financial oligarchy, cartels and the export of capital. The specific features are not taken out of history, but related to the historical development of capital; they are, as Lenin explains, transitional forms.

”

taken from this article: https://www.academia.edu/28968938/Theories_of_Imperialism

Ill be discussing Rotta et al’s paper on knowledge and value soon. And John Smith will be joining me on a panel of the economics of imperialism at this year’s Historical Materialism conference in London in early November.

I am looking forward to your discussion of Rotta’s paper. It has the following citation from the Grundrisse, which strikes me as provocative in this regard to say the least: “The theft of alien labour time, on which the present wealth is based, appears a miserable foundation in face of this new one, created by large-scale industry itself. As soon as labour in the direct form has ceased to be the great well-spring of wealth, labour time ceases and must cease to be its measure, and hence exchange value [must cease to be the measure] of use value.”

An excellent article Michael, but there are a few annoying typos:

Marx’s view that profit comes for [from?] the exploitation of labour…

(because European or Asian capitalist [capitalism?] is hardly mentioned and the periphery of the world economy is covered only in passing)

To say that, argued Marx[. remove the dot?] was to fail to see the real way in which the wealth created by the many and how it ends up in the hands of the few.

But if it means the “emergence of a new economic model..[.?] and a deep structural change in how the (capitalist) economy) works”

And that is clearly how Blakeley sees it. Accepting this new model implies that finance capital is the enemy and not capitalism as a whole, ie [i.e.,?] excluding the productive (value-creating) sectors.

“today’s corporations have become thoroughly financialised with some looking more like banks then [than?] productive enterprises”.

the weakening of the labour movement through slumps and ant[i?]-labour measures; privatisations etc[.?] and also a switch into investing in financial assets

We must fight for something more radical..[.?] because the capitalist model is running out of road.

P285. [p285?]

Rosa, yes it is annoying when there are typos etc especially when there are so many this time. Sorry for that but my editor (wife) was unavailable to check my errors. Thanks again for pointing them out.

That debt is not a specific form of exploitation can only be posited by an analyst who doesn’t have Third World perspective.

Hi Ivan, I dont have a Third World perspective any more because there are now only two worlds – imperialism and the periphery. But I know what you mean. You could argue that debt is a form of exploitation if you mean that by burying the peripheral economies in heavy debt, the imperialist countries can transfer much of the value created by workers in the peripheral economies and appropriated by domestic and foreign capitalists. It’s a way of transferring value across borders from the periphery to the imperialist economies. That is also done directly through trade as well. The essential point is that much of the value and surplus value created by workers in the ‘Third World’ is transferred to companies based in the imperialist economies. whether by debt and equity flows and/or by trade. I am well aware to this as member of the international debt audit network, a conference of which in Brazil from which I have just returned.

There is another form of value transfer which is often overlooked. IMF calls it ‘self insurance’. As financial markets are being opened up – as a result of structural adjustment programs – third world countries are forced to accumulate dollar reserves in order to protect themselves against sudden capital outflows and consequently devaluation of their currencies. These dollar reserves are mostly US treasuries and their main function is to secure the dollar’s position as a world currency. If the dollar devalues or the US interest rate drops third world countries lose. As far as I remember Lapavitsas mentions it in ‘Profiting Without Producing’.

MR: “there are now only two worlds – imperialism and the periphery.” China fits in the first, certainly as much as Germany or Italy.

Excellent /but

I completely agree with the main massage of articles :Before stealing something , that thing must have been produced , it is obvious unless somebody intentionally ignores the fact

But let’s look at it from another point of view

Looking at capitalism not only as a mode of production based on surplus value but also as a mode of distribution with thievery, embedded in it , gives us a theoretical base for unity of productive workforce which is exploited and rubbed at the same time , with nonproductive workers and small business owners who are just being rubbed

This unity is vital to become the majority

Imperialism started with theft of land. We even killed some of the people who lived on the land. Land was not produced. Later on we stole people and enslaved them You may say that the stolen people were ‘produced’, but the production can hardly be termed capitalistic. Then we forced the stolen people to work on the stolen land and then you can say that land was produced. When we realized that it was too expensive and too cumbersome to control all this land we gave it back to the original owners (except America). But we still wanted their resources, so we sent agents to force the new owners of the land to take on huge amounts of debt. This process is brilliantly described by former CIA agent John Perkins. By indebting these countries we could control their resources without having to spend huge amounts of money on controlling them physically. These are the two first stages of imperialism – land conquering and then debt. We are on our way to the third stage of imperialism and it is called “self insurance” by the IMF. In the process of indebting the countries, the IMF forced them to open up their economies to our goods and our finance in order to prevent them from processing and exploiting their own resources. Financial capital now flows freely in and out of third world economies and such flows can occur quite abruptly and wreak havoc on weak economies. In order to safeguard themselves they have to accumulate reserves in hard currencies – mainly dollars in the form of US treasuries. The third world countries lend out money to the US in order to “secure” themselves and by doing so they contribute to maintain the dollar’s status as a world currency with its “exorbitant privilege”. Besides if the dollar or the US interest rate drops the third world countries lose. All countries lose but the weakest economies are hardest hit. Is this theft? Obviously. Colonization is theft whether in the form of land grabbing or in the form of debt. With respect to “self insurance” Costas Lapavitsas calls it “Profitting Without Producing”.

The most interesting thing about this “revival” of leftist (“heterodox”) economists in the West post-2008 for me (I’m from History, not Economics) is how clearly they represent, in the intellectual arena, the terminal decline of the Western Civilization (Atlanticism).

Blakeley’s assumptions and solutions are completely out of time, out of place. She still talks as if the First World countries could still manage the world at will as it were 1946.

Her point of view — that we don’t live in a “manufacturing world” anymore — is completely biased and reflects the crescent parochialism of the Anglo-Saxon point of view, the same point of view that would be considered universal by everybody 30 years ago.

It’s not that the Anglo-Saxon intelligentsia changed: it’s the rest of the world that changed. Gone are the times an Anglo-Saxon economist could print whatever he/she wanted and the rest of the world automatically accepted that as cutting edge theory.

Finally, there’s the social-democratic issue.

Neoliberalism was actually created in the 1930s as an anti-social-democracy doctrine, not an anti-“communist” (i.e. revolutionary socialists) doctrine. That’s why social-democrats are essentially anti-neoliberals before being anti-capitalists. The social-democrats from Western Europe still believe that, as they achieved hegemony before, they can do so again — that’s what differentiate them from the Chinese, who many post-Keynesians swear are keynesians (and not socialists). The Chinese have a clear path to socialism (if they will be successful or not, that’s a completely different story).

Excellent!

Bourgeois economists deal in appearances, (exchange) values, trade, etc.

But, necessarily, capitalism has conquered Europe and the world by producing and reproducing itself materially in primal accumulation processes featuring mass murder and/or theft of actual people and expropriation of raw materials and goods (first in Europe, and then on a much more grand and violent scale (that continues), in Africa, Asia, and the New World…

It’s surprising that few commentators mention Samir Amin, a marxist scholar and activist who understood and applied the concept of surplus value on a global level, but within the foundational primal accumulation by theft and murder in the production and maintenance of the present system as experienced in the “peripheries”: 80 percent of the world’s actual consumer goods are produced in the Global South by permanently super-exploited labor.

‘Financialisation’ at the imperial centers is but a pale reflection of this material fact, not the cause.

I tend to agree with Blakeley, because household net worth in the U.S. has increased from $48 trillion to $108 trillion, 2009 to 2019, an increase of $60 trillion (Federal Reserve, Flow of Funds, page 2). I guess the GDP averaged about $15 trillion each year. Naturally the savings rate over 10 years was not 40% (adding $60 trillion in savings while creating $150 trillion in output, 60/150 = .4). So where did the $60 trillion come from? Financialization is a decent answer. Accumulation of capital is the motive, the raison d’etre of capitalism. Economist Lance Taylor calls it a dual currency event. One currency appreciates faster than the other, so the smart capitalist places his surplus (ill begotten) in the faster appreciating currency. Why would the financial assets inflate faster? Supply and demand, there are finite places to place capital, their value increases as more money seeks to harbor in those secure asset places. I suppose this is Blakeley’s argument. Didn’t Keynes call for the euthansia of the rentier? Maybe he was looking at this phenomenon? Blakeley’s book is a positive contribution because it highlights the stupidity of this economic system. Her theory may be wrong, exploitation may be better than theft, profit squeeze may be more accurate than debt or imbalance, but either way, the public is going to have to sort it out, and kill the rentier and greedy capitalist — accumulator. I began by reading Robin Hahnel’s book economic democracy, consumer councils informing producer councils, or libertarian socialism. Could I still buy my Toyota that goes 300,000 miles and more. Or would I have to stop driving entirely and take a cab? I don’t know. Cabs are OK, but what if I have to wait two hours for it to arrive? What then? Life is complicated.

«the public is going to have to sort it out, and kill the rentier and greedy capitalist — accumulator.»

A very big political difficult is that every worker turns into largely a rentier (or greedy financial capitalist), by necessity, on retirement, and retired rentiers are an increasing percentage of voters, in part because of longer typical lifespans, in part because most women have switched from having working sons as retirement sources of income to having financial and real estate assets.

This has created the politics of mass-rentierism (clintonism/blairism as well as reaganism/thatcherism), and most formulaic, sloganeering leftoids have not yet come to terms with that.

Going back to a defense of the “proudhonnistes”, there are some subtle points about “exploitation” defined as an exchange of labour-power as a commodity with commodities that embed less labour that than sold in the form of labour power:

* A lot depends on how big is that difference: if it is small, exploitation is not a big deal. KM obviously reckoned with some justification that in his time it was huge.

* A lot depends on the reason why that difference exists: if it is “buy low sell high” most people will regard it as entirely justifiable. If the use-value of the commodities a worker can buy by selling their labour-power is greater than the use-value of their labour-power for example. There is an issue if the difference arises from might-makes-right, and here KM argues that since workers effectively would starve without access to the means of production, there is effective blackmail in his view.

Now compare to rentiers “thieving”: the “proudhonians” effectively argue that the impact of paying rents on the living standards of today’s workers is much bigger than the impact of paying profits to capitalists, and that the reason why people pay 50-70% of their earnings in various forms of rent is because housing etc. are essentials to life and getting jobs, and rent is also entirely unproductive.

There is I think a good argument that KM really is defining profits as rents from giving access to the means of production too. If being employed, having a dwelling, having pension assets are all absolute necessities of life, so overcharging for these is always rent, the question becomes which has the biggest impact.

«the only way to take democratic control is to bring into public ownership the big five banks that control 90% of lending and deposits in Britain. Regulation of these banks has not worked and won’t work.»

But they are already entirely controlled by the state, their being in the private sector is a fiction, as the state provides well over of 100% of their capital. The issue is that their executive class and the political class overlap in large part.

«Would capitalists stand by while their powers of control are gradually or steadily lost?»

Depends on which capitalist faction: finance and property rentiers also “thieve” quite large sums from some important capitalist factions. Even if most of the *individuals* in those factions are also finance and property rentiers, which creates for them a conflict of interests.

«An investment strike would ensue and any socialist government would be faced with the task of taking over completely.»

Well, in the case of the “big five banks” that has already happened, and they have been effectively nationalized quite a while ago. No sensible capitalist will go long businesses devoted to the rentier interests of their management.

Anyhow “mixed economies” can work pretty well, as long as the majority factions of capitalists reckon that a socialdemocratic model that moderates the profit/rent they extract from workers works for them too. That can be a lot better than losing even more to unproductive rentiers. As KM and FE kept pointing out you can’t rush the natural evolution of the economy and the political forms that reflect its structure.

«So why not spell out fully a programme for a democratically controlled publicly owned economy with a national plan for investment, production and employment?»

To avoid scaring everybody? Politics also sometimes requires talking softly and making compromises. V. Ulianov advised avoiding adventurism as much as avoiding opportunism :-).

MR .- ’’The only way to take democratic control is to take the five large banks that control 90% of loans and deposits in Britain to public ownership. The regulation of these banks has not worked and will not work.” »»

Bl. “But they are already completely controlled by the state, their membership in the private sector is a fiction, since the state provides more than 100% of its capital.”

Yes, it is a fiction that banking is a private sector, that is to say, it is false that they are companies and the capital sector. If to the current control of the State over it, we add its direct, permanent, exclusive and PRIVILEGED access to the monetary funds of the Central B., it gives us that the bank is little or nothing private. Access to the Central B. which in ‘gross mode’ and without more detail allows you to obtain 90% of your benefits. It can be said, without any doubt, that the Bank already practices socialism today. The financial socialism. In fact, this real practice of socialism in banking is what allows you to achieve benefits and reach a level of operational security (the B. Central is your insurance policy) that the rest of companies do not have, nor have had since the creation of the first Central Banks (Bank of Sweden and B. of England, 17th century). Otherwise: several centuries of financial socialism has made it something powerful! An irrefutable proof of the efficiency and productivity of socialism!

And is the current western state and the socialist state of the twentieth century valid for the working class? Unclear. M. R.’s solution for banking reaching its public property is (or should be) a solution with a public property (a State) with command, control and control of workers. A workers and socialist democracy ..

Regards

The only way I see to take control is for the producers of wealth to organise politically and industrially as a class to have the power to establish social ownership and democratic control over the collective product of their labour and natural resources. Getting the producers (aka “the working class”) to act for themselves is and has been the political problem for those engaged in the praxis of social revolution since the ideological rot set in after the death of Engels in 1896.

To each new generation, the use-values produced by earlier generation of workers, say an abandoned house for example, is in principle the same as a commons was before the enclosure movement. It’s yours to use unless somebody can claim private ownership to the place, even though they doesn’t live in it it.

There is a difference between when capital get themselves a bigger part of the total surplus value by raising the rent – today often done by finangling up the price on houses and keeping the rent at the same percent of the market-price.

The gain from selling and re-selling houses at higher and higher prices are a finance-capitalistic way to get a bigger part of the total profit. This scheme also depends on that the lack of housing is not lessened by new-production. Which means that the production of surplus value in the building business gets smaller, and the surplus which the house-owning rentiers gets has to be produced in other parts of the economy?

And if this method to get the capitalists industrialists and rentiers taken together a bigger piece of a shrinking BNP- pie it causes stagnation by what could be defined as financialisation?

Completly translated in German:

https://marx-forum.de/Forum/index.php?thread/990-ist-kapitalismus-diebstahl-%C3%BCber-stolen-von-grace-blakeley/

Wal Buchenberg, Hannover

Wow, Wal, Thanks very much. Will post.

Well, I would say that if by “integration” and “stolen” we mean that the degree of primitive accumulation (see apple biometrical crimes against humanity machines, and all the data creeps of surveillance capitalism) has increased, or, the rate of exploitation must be adjusted then I would agree that indeed primitive accumulation, increments in the rate of exploitation, theft have increased.

But, yes if we make of “stealing” something exogenous to the capitalist system then your returns in confronting capital will be less when it comes to deploying strategies against them. Exploitation is what enables its laws of motion to unfold over every possible manifestation of abstract labor and proceed to accumulate capital to increase its capacity to exploit labor. The latter being its Sadean end in itself.

Exploitation is objective and a position of advantage regarding weakened labor (labor must accept to be commodified: exchange value if the laws of motion are to be activated). The battle of ideas would benefit from delivering the best possible strategies of how to target capitalist exploitation at the worksite. You may argue that the center has exported jobs, but its service sector is very labor-intensive. So, exploitation has yet to cease at the center. I used to be a cashier at BOA. Very labor-intensive: almost dementedly so. They were so bad that they insisted that any creative syllable that would emerge from your brain and would find its way into the pages of a book then this would mean that since you worked there, and they (did not) trained you (it is workers who do. They do not engage in enriching the workers life. But they are pretty good at charging fees because they selected some tie or another at some random day of the week) The book issue is truly a very vulgar expression of primitive accumulation after you have been properly exploited. Computers are now after everybody´s entrails, and the brain secretions: lovely. Clearly, there was a need being met somewhere, or, so the invisible hand was supposed to have told them.

So, yes. If one is to address capital it would be much better not to avoid addressing the central antagonism. Just look at all the whining, bitching, and threatening with regards to workers’ contracts: from cell phone companies to teachers, to auto-workers, etc. The point of antagonism is whether or not labor may find a way to afford itself to opt for something capital cannot offer: not commodifying itself. Is it possible to mobilize resources to develop relations of production where the reserve army is always mobilized (right at the moment capitalists begin to hallucinate through the price system that they are unworthy to enter material existence because they have been productive up until then: unemployment etc. Capital as media “You are fire” we hate Trump etc), and always offered ownership of the m.o.p´s over the lunch-box (wage goods: they are creeps. See entrails above, and the issue of surveillance capitalism) cash the exploiter insist on pretending he is contributing. It is a question of great interest to me as a political economist and analyst with a stolen pass.

Grace Blakely doesn’t seem to know much about this subject. She complains about the degree of “financialisation” but nowhere does she mention a bank system long advocated by numerous leading economists, including several Nobels, which would cut the bank industry down to size. It’s called “full reserve” banking or “sovereign money”. I’ve explained the basic rational of full reserve here:

https://ralphanomics.blogspot.com/2020/07/remove-bank-subsidies-and-existing_84.html

To any who may be interested, I have reviewed her latest book on my blog.

‘… These sections of The Corona Crash raise the key questions posed by state-monopoly capitalism, and point the reader in the right direction. Does this mean that Blakeley, Oxford-educated Corbynite, regular commentator on Novara Media, and former member of the Labour Party National Policy Forum, is following Lenin in arguing that the development of state-monopoly capitalism places the question of socialism – the smashing of the capitalist state and its replacement with the political rule of the working class – onto the political agenda?…’

https://aabogdanov719559657.wordpress.com/2021/07/23/state-monopoly-capitalism-and-socialism-a-review-of-grace-blakeleys-corona-crash/