The latest economic data from the major capitalist economies do not make pretty reading. The global slowdown, as measured in real GDP growth, is worsening. The first reading for real GDP growth in the US, for the first quarter of 2016, delivered an annualised rise of just 0.5%, or 0.125% quarter over quarter. If we compare the size of the US economy after taking into account changes in prices (inflation), with the first quarter of 2015, then the American economy is larger by just 1.9%. That’s the slowest rate of expansion since early 2014. The US economy, the best of the major capitalist economies, is still just crawling along.

There was only one of the top seven capitalist economies (G7) apart from the US that was growing by more than 2% at the end of 2015. It was the UK. Now in the first quarter of 2016, the UK reported an expansion of just 0.4%, so that the British economy was larger by 2.1% compared to the first quarter of 2015. And most forecasters are expecting that growth rate to slip below 2% yoy in the current quarter we are now in (April to June).

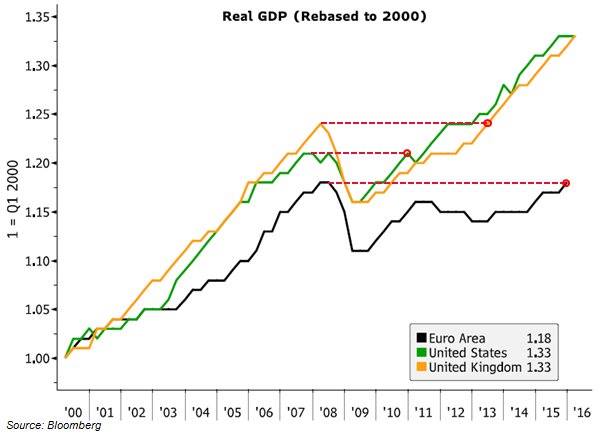

In the first quarter of 2016, the Eurozone group of economies grew faster than the US or the UK! The Euro area rose 0.55% compared to 0.4% in the UK and just 0.125% in the US. The EU region as a whole rose 0.5%. For the first time, Eurozone GDP in real terms has returned to its peak before the Great Recession – but three years after the UK and six years after the US! Compared to this time last year, Eurozone real GDP is up 1.53%. However, Eurozone growth has also slowed from 1.58% yoy in Q3 2015 to 1.55% in Q4 2015 and now 1.53%. It’s just that the US and the UK economies have slowed even more.

Now readers of my blog will know ad nauseam that this rate of growth in the major economies is an indication that the world economy remains in what I call a Long Depression (Jack Rasmus calls it an Epic Recession), where trend real growth is much lower than the long-term average and well below the rate of economic growth before the onset of the Great Recession in 2008-9. The latest quarterly figures for real GDP growth do no more than confirm that thesis.

Mainstream economics is reluctant to accept this view. Not only do the major official economic forecasters like the IMF, the OECD and EU Commission, after announcing yet another year of slow growth, keep forecasting a revival for the next year, but the consensus view is that the slowdown will end and growth will recover.

For example, Keynesian economist and former chief economist at Goldman Sachs,Gavyn Davies, now runs a forecasting agency, Fulcrum. Fulcrum and Davies told readers of the FT this week that, although real GDP figures are looking bad, GDP data look backwards, not forwards. And looking forward, things are getting better. Apparently, global activity is now only just below trend growth of 3.6% a year and the world economy has “again stepped back from the brink of outright recession”. So not to worry.

Moreover, there has been a move to dismiss the validity of the idea of GDP altogether as an indicator of prosperity or the health of the capitalist economy. The Economist magazine presented all the well-versed arguments for the weaknesses in the measurement of an economy using GDP: it does not measure the value of financial services properly, or the quality of new output and the gains of the new ‘disruptive technologies’ etc.

Many of these arguments may be right. But it is no accident that the Economist wishes to dismiss the GDP measure only when it produces depressing results for capitalism. And GDP does provide a reasonable benchmark for ‘economic change’ over the long term, if not for ‘economic welfare’, i.e. the value and quality of living for the average person.

So if we work with the GDP data as we have it, we find confirmation of my view that we are in a Long Depression. The best measure of this, in my view, is real GDP (i.e. after inflation) per person. Real GDP per capita takes into account any expansion of population that would explain some growth in GDP just because of more people. This applies to countries like the UK where immigration from Europe has been considerable in the last ten years.

After a look at the data,I found that between 1998 and 2006, average annual growth in real GDP per person was much higher (1.5-2% a year) than between 2007 to now (under 0.5% a year) in all the major advanced capitalist economies. The change was particularly sharp in the US, the UK and the Eurozone, but less so in Japan (where the population has been falling). In Italy, real GDP per head has been negative since 2007 and France almost zero. So for nearly ten years, real GDP growth has been depressed way below previous averages.

In a recent post on his blogsite, British Keynesian economist, Simon Wren Lewis, now an adviser to the British opposition Labour Party, put up the question: how do we explain the last ten years of slow growth or depression?

According to Wren-Lewis, the cause of the depression is the after-effects of the Great Recession and the austerity policies of the governments subsequently. The Great Recession was caused by a ‘lack of demand’ I suppose, although Wren-Lewis is not clear on this. But no doubt he would agree with that other prominent Keynesian economist, Joseph Stiglitz, another ‘advisor’ to the British Labour party, who stated baldly at the time (2009) that “The lack of global aggregate demand is, in a sense, one of the fundamental problems underlying this crisis. Lack of aggregate demand was the problem with the Great Depression, just as lack of aggregate demand is the problem today.”

Now I have argued in this blog that to say the cause of the Great Recession was due to a lack of demand is bit like saying that that the cause of the streets being wet today is because it is raining today. That tells us nothing about why it is raining today and/or what causes rain to happen. Describing the Great Recession as a lack of demand is just that, a description, not an explanation.

But Wren-Lewis goes onto to consider why the Great Recession has morphed into a Long Depression. Apparently, it is partly because of the left-over effects of the Great Recession, but mostly because of ‘austerity’ measures by governments that has prolonged the recession instead of boosting government spending to get a recovery.

He admits that the last ten years have not turned out as the mainstream model might have expected, because this time, for some reason monetary policy has failed. “Here it is helpful to go through the textbook story of how a large negative demand shock should impact the global economy. Lower demand lowers output and employment. Workers cut wages, and firms follow with price cuts. The fall in inflation leads the central bank to cut real interest rates, which restores demand, employment and output to its pre-recession trend.”

But this time, interest rates have been taken to zero with little effect: the economies are zero-bound so more drastic action is needed. “We know why this time was different: monetary policy hit the zero lower bound (ZLB) and fiscal policy in 2010 went in the wrong direction.” This was a similar conclusion that Keynes himself reached when his easy monetary policy option also failed in the early 1930s.

Well, Marxist economics could have told the Keynesians that easy money would not do the trick. But it would also tell the likes of Wren-Lewis that ‘reversing austerity’ will not either.

The implication of the Wren-Lewis position and that of all Keynesian explanations of the last ten years is that if governments had never adopted ‘neo-liberal’ policies of austerity, there would never be any recessions. But what if the cause of the Great Recession and the subsequent Long Depression is not the product of a ‘lack of demand’ as such or ‘pro-cyclical’ government spending policies (austerity) but is caused by a collapse of the capitalist sector, in particular, capitalist investment. And that investment collapsed because profitability in the capitalist sector fell, then the mass of profits fell, leading to investment, employment and incomes to fall, in that order. Then it’s the change in profits that leads to changes in investment and demand (consumption), not vice versa, as the Keynesians argue.

I have presented evidence for this cause of the cycle of boom and slump on this blog on many occasions. And to quote the latest empirical study by Jose Tapia Granados (a follow-up to this) “Data show that profits stop growing, stagnate, and then start falling a few quarters before the recession, when investment and wages start falling.” Tapia concludes that “The evidence is quite overwhelming that profits peak several quarters before the recession, while investment peaks almost immediately before the recession. Then profits recover before investment does, as illustrated by the investment trough that occurs around the end of the recession or the start of the expansion but following the profit trough for at least a few quarters”.

Currently, as I have shown, global corporate profits growth has dropped to near zero and in the US corporate profits are falling. If this is sustained, investment will contract and the major economies will drop into a new recession. Indeed, the most telling figure in the latest US GDP results was for business investment. In the first quarter of 2016, that fell 5.9% annualised, the biggest quarterly fall since the end of the Great Recession. For the first time, business investment was smaller than this time last year (by 0.4%). And even taking into account investment in housing and government, total investment fell. The fall in business investment has been mostly in energy and mining as oil prices collapsed – energy investment is down 75% since 2014!

Personal consumption growth ticked along at 2.7% yoy. Many mainstream economists argue that this is what matters in an economy because 70% of the economy is consumption. But in a capitalist economy, it is investment that decides, in particular business investment. If the negative trend in business investment continues, the US economy will not escape another recession.

The weird irony of the Keynesian/Wren-Lewis position is to argue that reducing profitability and profits (and thus raising wage share) should benefit the capitalist economy by raising consumption. Wren-Lewis notes the argument of fellow Keynesian Paul Krugman that high profit margins for US corporations might be a result of monopoly rents (control of the market) and if we get more ‘competition’, profit margins will fall to the benefit of all. I have dealt with the bogus mainstream argument in an article for the Jacobin online magazine.

As Wren-Lewis puts it, if profit margins fall back, that would be “an optimistic story, because an additional demand stimulus would increase wage but not price inflation, and we would see rapid growth in labour productivity as firms reversed their earlier labour for capital substitution.”

The Keynesian conclusion is that lower profits for capitalism will make capitalism work better because there will be more competition and less monopoly; and less profits means more wages and so more demand. The Marxist conclusion is the opposite: lower profitability and profits will lead to lower investment and productivity growth and a prolongation of the depression. Only a large destruction of capital values in a slump that restores profitability will create eventual recovery in a capitalist economy.

In effect, what the Keynesians want to see is an end to ‘neoliberal’ policies and their replacement by what used to be called ‘social democratic’ policies of government intervention to manage the capitalist economy and boost investment and demand. With this sort of help, capitalism can be restored to provide prosperity for the majority, as it was in the Golden Age of the 1960s when Keynesian policies ruled supreme.

This is the argument that Keynesian Brad Delong and his fellow author Stephen Cohen argue in their new book, Concrete Economics. It was also the argument presented by Brad Delong at this year’s conference of the American Economics Association (ASSA) when critiquing my own paper there on The Long Depression, the arguments of which he totally ignored.

It is a (Keynesian) myth that the brief Golden Age of fast growth, full employment and low inequality in the 1950s and 1960s was due to Keynesian economic policies. As I have shown on this blog and elsewhere, that brief period of capitalist success (confined to the advanced capitalist economies) was due to relatively high profitability of capital after the world war and the relative strengthening of the labour movement in conditions of relatively full employment that forced concessions from capital.

The subsequent neo-liberal period was not the result of right-wing governments ‘changing the rules of the game’, to use Joseph Stiglitz’s phrasing, but the crisis of falling profitability that necessitated new reactionary policies and governments to restore profits at the expense of labour. While profitability in the major economies remains near post-war lows, no amount of Keynesian monetary and fiscal policies will deliver a new ‘Golden Age’.

Brad Delong told us Marxist economists at ASSA that we are pessimists ‘waiting for Godot’, when capitalism can be made to work with the ‘concrete economics’ of Keynesian social democracy. Well, the last ten years cast doubt on that view and the next few years will see who is right.

Thanks you, Michael, for this good piece. A couple of small things: the years in the first graph are distorted. Jacobin is a magazine or online not a newspaper.

thanks, will correct

Mr. Roberts, Thank you for the lucid explanations for non-economists such as myself.

A related point, which I wonder what you think about:

I. Wallerstein observes that capital is never an abstract entity; it is always concrete in that, in each stage of capitalist development, a particular industry (or sub-industry) or set of industries lead the development of capitalism (both economically and politically). For example, in the U.S. the rail industry used to be hegemonic in the 19th century, then lost that hegemony, and so on.

So, if we take this dimension of capitalist development into account, does that not also mean that at particular stages, particular industries’ profit margins are the more determining ones, the important ones, not the overall profit margins for the capitalist class as a whole?

Can we assume that the higher-than-average profit margins of particular predatory capitalists, not the average profit margins, determine the political developments regulating the functioning of the capitalist class as a whole?

In short, can we conclude that *particular* industries (not capital in general) can be flourishing with huge profit margins, and those are the ones who dictate the terms of the political agendas and policies?

I take Wallenstein’s point that each ‘wave’ of capitalist development will have ‘leading’ sectors. And leading sectors may well be the profit margin leaders. However, I am not sure that these ‘leaders’ dominate political and economic policy for the capitalist class as a whole. That policy has wider class interests (versus labour most important) and often politics can be controlled by ‘past leaders’ and not in the interests of the new.

“But this time, interest rates have been taken to zero with little effect: the economies are zero-bound so more drastic action is needed. “We know why this time was different: monetary policy hit the zero lower bound (ZLB) and fiscal policy in 2010 went in the wrong direction.”

That happens also to be Boffy’s explanation, isn’t it?– a la 1847-8? 2008-9 was a monetary crisis, responding well to the lowering of interest rates until the evil-austerians subverted the course of capitalist recovery?

Reblogged this on 21st Century Theater.

Another fantastic post, Michael, but I’m just not so sure I agree with you about the relationship between profits and investment; I don’t think it’s quite as simple a causal relationship as you conceive it to be.

“The Great Recession and the subsequent Long Depression…is caused by a collapse of the capitalist sector, in particular, capitalist investment. And that investment collapsed because profitability in the capitalist sector fell, then the mass of profits fell, leading to investment, employment and incomes to fall, in that order.”

We all agree that the rate of profit has been declining since the 70’s. While you believe this is the result of a scheduled downturn in the profit cycle, what if it was caused by a crisis of overproduction and under-utilization of capacity in the global manufacturing sector (due to the rise of Germany and Japan)? In order to keep up with the competition, businesses have only invested in productive capacity to undercut rival firms (greater efficiency means lower costs of production), exacerbating the problem. But as credit became easier and easier, firms became much more able to access credit and make these investments, regardless of profit margins. I’m not convinced that investment necessarily falls if profits decline; I believe that firms in this era are able to saddle themselves with debt (loans taken out for investment) and choose to do so to try to undercut the competition and keep up.

If we are indeed suffering from a crisis of under-utilization of capacity, another large recession and destruction of capital values will not be enough to restore profitability and get the economy growing again in the 2020’s, at least not the way it did in the 90’s and 00’s. Governments will respond by making war (distraction), “social democracy,” or blowing bubbles in order to try to get GDP growth to reach desirable rates–or at least do what can be done to satisfy the masses.

I like this post a lot but, I think this is correct from a cyclical perspective i.e. for a typical business cycle 3-7 years but from a structural perspective 20-30 yrs the consumer is the key driver of GDP. If you looks at wages growth vs. productivity and vs. investment in most western economies their is clearly a structural problem at an income level and if you look at household balance sheets consumers are tapped as to how much debt they can add, plus credit standards are tighter post the GFC. CEO’s and board members are getting paid very well but middle & lower income workers are not thus profit margins are high and sales growth is low as middle and income earners spend most of their income. Aggregate demand on a structural basis can’t lift substantially unless low and middle workers get pay rises equal to productivity, this won’t happen unless there is some sort of circuit breaker intervention or a moral agreement by CEO & boards to pay staff wages increases inline with productivity or permanent tax cuts for workers. The answer in economics always lies in the accounting truth. Accounting is unbiased.

“He admits that the last ten years have not turned out as the mainstream model might have expected, because this time, for some reason monetary policy has failed. “Here it is helpful to go through the textbook story of how a large negative demand shock should impact the global economy. Lower demand lowers output and employment. Workers cut wages, and firms follow with price cuts. The fall in inflation leads the central bank to cut real interest rates, which restores demand, employment and output to its pre-recession trend.”

The monetarists, Austrians and Keynesians do not seem to recognise the linkage in all of these factors.

Has “monetary policy failed”? It did not fail to end the credit crunch in 2008/9, just as Marx and Engels indicate it worked rapidly to end the credit crunches in 1847 and 1857. Combined with fiscal stimulus it also worked to end the economic contraction that followed the financial crisis. That economic contraction was not as severe as the 37% contraction that Marx says occurred as a consequence of the 1847 financial crisis, for example.

But, monetary policy has only failed more generally since then if you believe that the intention of that monetary policy for conservative governments was to stimulate economic activity. It wasn’t! Those conservative governments had to apply monetary and fiscal policy in 2008/9, because of what they saw as an existential threat to the system as a whole. Once that existential threat was seen to have disappeared they went back to doing what conservative governments had been doing for the previous thirty years, which was again to blow up asset price bubbles, which is the form the wealth of individual capitalists today takes.

Marx makes the same point about the role of conservative governments and of the bankers, financiers, and stock jobbers whose interests they serve. They are more than prepared to see real capital destroyed, and the economy tank in order to keep those prices of fictitious capital high, and maintain the illusion of wealth they represent. Given the number of voters today who are also caught in the illusion of wealth represented by high house prices, high valuations on their pensions, and ISA’s those governments have an even greater incentive to follow such policies. And as I quoted John Weeks as saying a while ago, the News Channels Business programmes feed that by effectively being nothing other than a weather forecast of speculation.

The difference between 1847/57 and 2008/9 is that in those earlier financial crises, after the credit crunch was resolved monetary policy remained based only upon what was required for the circulation of commodities. In 1847, no additional money was thrown into circulation by the authorities. Just suspending the bank Act was sufficient to end the credit crunch, as all those who had been hoarding money threw it back into circulation, and credit expanded.

Since 2008, way more liquidity has been thrown into circulation than was required for the needs of commodity and capital circulation. Its purpose was precisely to reflate asset price bubbles and thereby protect the fictitious wealth of private capitalists, and the balance sheets of financial institutions. It has succeeded spectacularly in that regard as witnessed by the current bubbles in stock, bond and property markets! No inflation? How about the 300% inflation of the S&P 500, the doubling of the DOW, and the bubble in bond prices that crushes pension funds? How about the rise in property prices in the US, back to 2007 levels that is again squeezing ordinary buyers out of the market, and the huge rise in London property prices, that is bringing in speculators from all over the world, unconcerned about whether they can make any rental yield (in fact many new developments left empty for years) because they are only interested in making huge, quick capital gains.

And they do not see the connection between that, and the lack of investment. There is a lack of investment in the true sense, but there is no lack of “investment” in the sense that there has been this astronomical investment of funds into speculation, into the buying of shares, bonds, and property to obtain capital gain. Why would you invest in productive activity that might bring you a 10% profit of enterprise, when you could speculate in stocks that would bring you 10% capital gain in a matter of weeks or months, or speculate in property that might bring the same kind of capital gains, and much more?

What the policies of QE and easy money have done after 2008 is what they were intended to do which is to blow up those asset price bubbles and protect the fictitious wealth of private money capitals, and banks. In so doing they have acted like black holes whose gravity is so great that they suck all other liquidity and financial activity into them. Anyone with the savings or money-capital to be able to do it has seen it as a no brainer to shove their money into these rapidly rising assets, that have the added benefit that they are underwritten by central banks, and some of them by governments that promote various other scams to keep asset prices high such as the Help To Buy, Buy To Let, and Right to Buy scams introduced by the Tories.

In so doing, alongside the policies of austerity they have the inevitable consequence of sucking more liquidity and more potential money-capital from profits into that financial speculation, and so out of general circulation. It is a policy which necessarily results in a deflation of commodity prices, therefore, at the same time that it causes a hyper inflation of asset prices.

And the more it causes that deflation of commodity prices, the more it undermines real economic activity, the more the authorities are pressed to do even more of what is causing the problem, and which thereby undermines the basis of the interest and rent upon which ultimately the asset prices will have to be based. It creates the basis for a much, much bigger financial crisis than 2008.

Its like someone suffering an anxiety attack and mistaking it for an asthma attack. So they keep taking an adrenalin inhaler to relieve what they think is the asthma and all the time keep speeding up their heart rate and making the anxiety attack worse, until eventually they have a heart attack.

Rather than aim at easy Keynesian targets, how about addressing what Alan Freeman has been writing about the similarity between the programmatic positions of Keynes and Marx?

Hi Paul It would nice to think that Keynesian economics is an easy target. Maybe, it is for you, but as it rules the roost in the left of the labour movement, it is a target to be aimed at, even so.

Actually I did take aim at Alan Freeman’s arguments in a recent post. https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2016/02/28/g20-and-the-mainstream-solutions-to-a-global-slowdown/

http://marx-forum.de/Forum/gallery/index.php/Image/847-Einkommensentwicklung-1980-2015/

A graphic like this one shows better as the GDP how capitalism works.

For each of the six countries two curves are shown:

a) The real income since 1980 of the richest decile

b) The real income since 1980 of the poorest decile.

Source: http://gcip.info

Thank you so much for your revolutionay marxist works. From Canada with comrads

Reblogged this on Reconstruction communiste Comité Québec and commented:

AVERTISSEMENT: Ceci est une traduction Google avec quelques ajustements des camarades de Reconstruction communiste. Elle contient sans doute quelques inexactitudes. Nous avons toutefois pensé vous le présentez parce que cet article vaut la peine d’être connu de nos lecteurs francophone en raison de son champ d’étude théorique marxiste, l’économie politique, un sujet d’étude avec lequel Karl Marx a réalisé son oeuvre magistrale « Das Kapital ». Or, non seulement le matérialisme dialectique de Karl Marx fut largement développé dans « Le Capital», mais l’économie politique marxiste elle-même est un sujet d’étude largement abandonné par les marxiste-léninistes contemporains, qui s’en sont peu préoccupés ces dernières années, Michael Roberts étant un des rares économiste marxiste à reprendre les thèses de Karl Marx.

Interesting read, I’m perplexed that you didn’t mention steady state equilibrium. Perhaps western economies are not growing because they’re approaching steady state.

Cant do all in one post – I dont agree with Keynes that the future of capitalism is a gradual move to a ‘steady state’ of superabundance and the end of the rentier. The rentier has never been so dominant!

Thanks for pointing to where you replied to Alan, but I dont think you do him justice there. You take aim at the Keynesians not Keynes as defended by Alan. You say “The key point right now in the current global slowdown is the Keynesian analysis says that the problem is a lack of aggregate demand and increased government spending through the Keynesian demand multiplier can do the trick.” The key difference between Keynes and the Keynesians here is according to Alan that Keynes too saw the decline in the rate of profit as a key factor, and that he saw the solution not in ‘increased government spending’ but in the socialisation of investment. The key difference between the period between 1945 and 1978 and now was the leading role of the state in carrying out investment and making sure that investment as a fraction of profit was much higher than it would have been under normal capitalist conditions.

The 45 government and the subsequent labour governments took large sections of industry into state ownership, built half the houses in the country, and by means of these tools were able to achieve significantly higher levels of investment than private profit making industry would have done. You only have to contrast the vigourous development of nuclear power in the late 50s and 60s by state capital with the complete inability of private capital to build a single nuclear station since privatisation to see the difference.

It is not state demand management that was the key, but state investment, that is what Alan is drawing attention to.

When you say:

“The problem with the latter is that profitability can only be restored through the destruction of value by stopping investment, liquidating old capital and making millions unemployed. That is the contradiction of capitalism that Keynes did not recognise, along with all mainstream economics.”, you are I think targeting the Keynesians not Keynes. Keynes saw the falling rate of profit as inevitable and hence the necessity for the state to embark on large capital intensive projects that would not be viable for private investment.

Paul You make some good points but I dont agree with Keynes’ view of the falling rate of profit to a steady state equilibrium and the euthanasia of the rentier. It’s an apologetic and optimistic view of capitalism (which is sustained, according to Keynes, with a little help from state investment occasionally). The ‘economic problem’ as Keynes called it will not be resolved by the time of his (and our) grandchildren with the capitalist mode of production still dominant – and it wont fade away as Keynes vaguely suggests. To equate Marx’s view of crisis and contradiction in a profit-making privately owned economy with Keynes’ gradualist view of a disappearing economic problem is incorrect, in my view. But this sounds like an excellent area for debate and discussion without easy targets.

Are you sure Keynes thinks it will gradually fade away?

His point on this I think was that “we’re all dead in the end.” I think he did believe in the inevitable destruction of capitalism; he just thought that it would occur after his grandchildren died. And thus he saw little point in discussing it, particularly during that era, when such talk would get you labeled as a red. This is someone who told everyone he had never read Marx, for example, and I don’t believe it one bit. I highly doubt a thinker as great as Keynes would have ignored a philosopher as important as Marx. But he felt he had to ensure that no one on the far right could label him as a Marxist-influenced leftist.

Very interesting. Is there any evidence for that? Anything in his correspondences, or the recollections of others about Keynes indicating that was what he thought?

Sartesian:

I don’t believe that Keynes was influenced by Marx; that’s not why I brought up the example of his claim to never have read Marx. My point is that Keynes was very conscious to take the necessary steps to avoid his work being labeled as ‘socialist’ in any way. Marx had as big of an influence as any thinker in history, and I just can’t see someone like Keynes refusing to even read him.

There is a plenty of evidence that Keynes believed capitalism to be inherently unstable and that he believe it would implode one day. But he probably thought this would happen after the death of his grandchildren, and thus there would be absolutely nothing to gain from explicitly making such claims (and everything to lose).

Well, ok, but this is what you wrote:

“This is someone who told everyone he had never read Marx, for example, and I don’t believe it one bit. I highly doubt a thinker as great as Keynes would have ignored a philosopher as important as Marx. But he felt he had to ensure that no one on the far right could label him as a Marxist-influenced leftist.”

I asked is there any evidence to contradict Keynes’ own statements?

The answer, I guess is “no,” so what we’re left with is….speculation. Appropriate I guess, and appropriately pointless.

“To equate Marx’s view of crisis and contradiction in a profit-making privately owned economy with Keynes’ gradualist view of a disappearing economic problem is incorrect, in my view. ”

But therein lies another element of the contradiction, because as Marx and Engels describe, even by the latter part of the 19th century, we did not have a privately owned economy! The private ownership of productive-capital was already by 1865 an anachronism, as Marx sets out in Capital III, Chapter 27, and as Engels describes in his Supplement on the Stock Exchange, and in his Critique of the Erfurt Programme, where he says,

“What is capitalist private production? Production by separate entrepreneurs, which is increasingly becoming an exception. Capitalist production by joint-stock companies is no longer private production but production on behalf of many associated people. And when we pass on from joint-stock companies to trusts, which dominate and monopolise whole branches of industry, this puts an end not only to private production but also to planlessness.”

The whole point, as they set out is that private wealth takes the form then not of ownership of productive-capital, but of loanable money-capital, of fictitious capital in the shape of bonds, shares and property from which they derive interest and rent, in an antagonistic relation to the interests of the now socialised industrial capital, and its need to produce profit so as to accumulate.

As Engels sets out in Anti-Duhring, the epitome of that dichotomy is the concentration of all productive-capital in the shape of state-capital, with the private money-lending capitalists then simply existing as coupon clippers deriving their interest from the ownership of their state bonds, which derive their interest from the profits produced by the now state capital.

And the further paradox that arises from this follows from Engels suggestion that under such conditions society would not tolerate for long the continued existence of such a small class of socially useless parasites. If all productive-capital were state capital, then new loanable money-capital arising from profits would settle in the hands of the state itself.

But, as Marx describes in Capital II and III, Capital like land and labour has no value, as opposed to the commodities that comprise the elements of productive and commodity-capital. That caused great confusion to bourgeois economists like the banker Overstone, who did not understand this difference between those commodities which are the product of labour, and so have value, and capital (as self-expanding value, the ability to produce average profit) which is not a product of labour, and so has no value. That confusion, Marx describes in Capital III, led them into all sorts of problems in trying to explain the price of capital and its movement as a consequence of the price and demand and supply of those commodities. The simple question to the bourgeois economists who do not understand this difference is this. The use value of capital is to produce profit, and as Marx says this profit may be £100 today and £200 next week. So tell me, what is the value of this capital, how much labour-time is required to produce this use value of being able to produce this profit that might be £100 today, and £200 next week?

As Marx sets out, in Capital II and III, capital not only has no value, but it is never bought and sold or exchanged. It is only commodities that are so exchanged. A capitalist does not buy productive-capital, Marx explains but buys say a machine, which may or may not function as capital. The capitalist does not sell commodity-capital, Marx explains but only commodities that comprise it, the capitalist metamorphoses the commodity-capital into money-capital, and thereby retains the capital, i.e. its potential to produce profit. Capital can only be sold as a commodity, Marx explains when an average rate of profit is established, and so where this use value of being able to produce the average rate of profit can be sold. But, he also explains in Capital III that precisely because capital has no value, capital as a commodity, as the ability to produce average profit, can have no price of production, around which its market price rotates, and so there is no natural rate of interest, in the way that there is a natural price for other commodities that have value.

A market price for capital, the rate of interest, only exists, Marx explains because of the existence of a class of money-capitalists. Because capital has no value, because it is not the product of labour, the market price of capital, Marx explains is solely a function of the interaction of the demand and supply for money-capital, its upper limit thereby being set by the fact that productive-capitalists will not (except during crises) pay a higher rate of interest than the average profit they can obtain from use of the capital, and a lower limit set by the fact that owners of money-capital will not sell its use value for nothing.

But, Marx sets out in Capital III, if there are no class of money-capitalists then this interaction of the demand and supply for money-capital disappears, and so the market price of capital also disappears. A state which took in all realised profits, and so controlled the supply of money-capital, would also be the same state that exercised the demand for that money-capital, and could allocate it as it considered would be most effective.

As Marx points out the category of interest can itself only exist, because of the formulation of a “rate of interest”, as a price of capital. But, this price of capital is necessarily irrational, as Marx points out (in the same way as he points out that a price or value of labour is irrational) because capital (self-expanding value) has no value, just as asking what the value of labour is is as irrational as a yellow logarithm, or asking how long length is, because as Marx says, “Value is Labour“.

Just as bourgeois economists confuse the value of labour (not a commodity, but the essence and measure of value, and consequently not itself the product of labour) with the value of labour-power, a use value in all modes of production whose own value is determined by the labour-time required for its production, and thereby able to become a commodity as wage labour under capitalism, so they confuse the value of the commodities that comprise the physical elements of capital, or money with capital itself (self-expanding value).

The rate of interest arises as Marx shows purely from the competition between two classes of capitalists industrial capitalists who demand money-capital and money-lending capitalists. But, this price of capital, the rate of interest is irrational, as Marx sets out, precisely because capital has no value. It is sold as a commodity, whose use value is to produce average profit, but it has no value or price of production to act as the equilibrium point at which demand and supply equate. The market price becomes simply a battle between these two different classes of capitals over the demand and supply of the money-capital.

“We have seen (Book II, Chap. I), and recall briefly at this point, that in the process of circulation capital serves as commodity-capital and money-capital. But in neither form does capital become a commodity as capital.

As soon as productive capital turns into commodity-capital it must be placed on the market to be sold as a commodity. There it acts simply as a commodity. The capitalist then appears only as the seller of commodities, just as the buyer is only the buyer of commodities. As a commodity the product must realise its value, must assume its transmuted form of money, in the process of circulation by its sale. It is also quite immaterial for this reason, whether this commodity is bought by a consumer as a necessity of life, or by a capitalist as means of production, i.e., as a component part of his capital. In the act of circulation commodity-capital acts only as a commodity, not as a capital.”

(Capital III, Chapter 21)

“In the same way as money-capital it really acts simply as money, i.e., as a means of buying commodities (the elements of production)…

But in so far as they actually function, i.e., actually play a role in the process, commodity-capital acts here only as a commodity and money-capital only as money. At no time during the metamorphosis, viewed by itself, does the capitalist sell his commodities as capital to the buyer, although to him they represent capital; nor does he give up money as capital to the seller. In both cases be gives up his commodities simply as commodities, and money simply as money, i.e., as a means of purchasing commodities.” (ibid)

“It is this use-value of money as capital — this faculty of producing an average profit — which the money-capitalist relinquishes to the industrial capitalist for the period, during which he places the loaned capital at the latter’s disposal.” (ibid)

“What the buyer of an ordinary commodity buys is its use-value; what he pays for is its value. What the borrower of money buys is likewise its use-value as capital; but what does he pay for? Surely not its price, or value, as in the case of ordinary commodities. No change of form occurs in the value passing between borrower and lender, as occurs between buyer and seller when it exists in one instance in the form of money, and in another in the form of a commodity.” (ibid)

“The value of money or of commodities employed as capital does not depend on their value as money or as commodities, but on the quantity of surplus-value they produce for their owner. The product of capital is profit.”

“Furthermore, capital appears as a commodity, inasmuch as the division of profit into interest and profit proper is regulated by supply and demand, that is, by competition, just as the market-prices of commodities. But the difference here is just as apparent as the analogy… As soon as supply and demand coincide, these forces cease to operate, i.e., compensate one another, and the general law determining prices then also comes to apply to individual cases. The market-price then corresponds even in its immediate form, and not only as the average of market-price movements, to the price of production, which is regulated by the immanent laws of the mode of production itself…But it is different with the interest on money-capital. Competition does not, in this case, determine the deviations from the rule. There is rather no law of division except that enforced by competition, because, as we shall later see, no such thing as a “natural” rate of interest exists. By the natural rate of interest people merely mean the rate fixed by free competition. There are no “natural” limits for the rate of interest.” (ibid)

“It is not until capital is money-capital that it becomes a commodity, whose capacity for self-expansion has a definite price quoted every time in every prevailing rate of interest.” (Chapter 24)

Its this division between the interests of these two classes of capitalists industrial capitalists and money-lending capitalists that I have described in the comments above, and which result in a price for capital, in the shape of the rate of interest that leads to the situation seen today, whereby private wealth in the form of that fictitious capital, money-lending capital seeks to maintain the inflated prices of those asset prices, and diverts huge amounts of potential money-capital, derived from profits, into speculation.

It results for example in the vast majority of bank lending in the UK going not to finance productive investment but to promote mortgages and other property associated loans, which act to inflate property bubbles further.

The answer to this is not the hope for some class “neutral” state to come along to nationalise the banks etc. as Paul Cockshott hopes, and as Fabians and Lassalleans have been suggesting for more than a century, but is for workers to insist on having control over their capital, the socialised capital of modern industry, rather than that control being appropriated by the lenders of money capital.

There is no reason why shareholders should have such control, any more than bondholders or the provider of a bank loan. Even Haldane and Clinton have pointed to the need for a reform of corporate governance, and Germany already has the Co-Determination Laws, The 1975 Bullock Report proposed that half of the board members of UK companies should be elected by the trades unions, and similar proposals are included in the EU’s, Fifth Company Law Directive.

And, of course, such democratic control over the socialised capital is already exercised in worker owned co-operatives.

Yeah, these are points of sorts.

I still don’t know how we conclude a, “similarity between the programmatic positions of Keynes and Marx”

I can imagine that Marx would have detested Keynes even above Malthus. I hope so because that is the way I feel about him.

It’s just Cockshott being Cockshott, trying to convince everyone that a Labor govt. can make capitalism work for all.

To be fair to Corbyn I don’t think you would ever hear him say,

“How can I adopt a creed which, preferring the mud to the fish, exalts the boorish proletariat above the bourgeoisie and the intelligentsia, who with all their faults, are the quality of life and surely carry the seeds of all human achievement”

Excuse me while I throw up!

My point was that Alan Freeman, a prominent marxist economist has recently written a number of papers and blog posts arguing that there was considerable ‘programatic’ similarity between Marx and Keynes in terms of the immediate measures both proposed. see for example

https://canadiandimension.com/articles/view/keynes-and-the-crisis

and here

https://www.academia.edu/22259154/Self-imposed_division_overlooked_continuity_Marx_Keynes_and_the_Rate_of_Profit

Freeman argues that there is a big difference between Keynes and the Keynesians. He is not saying that Keynes view of crisis was identical to that of Marx, but that there were similarities and that the immediate programmatic measures advocated by Keynes largely overlapped with those advocated by Marx in the Communist Manifesto, he says:

” I will argue that Marx and Keynes shared a recognition of all these facts, differing in one essential, political respect: that of agency. Marx held that a new type of state, politically free of control by the property-owning classes, was needed. Personally, I agree with him, but this is a matter of discussion and experience. They key point is the economic programme of this state, in modern terms Keynesian-Georgist: it would nationalise the banks, means of communication, land and transport; it would introduce a heavy progressive income tax, ‘extend’ state industry, introduce full employment and also a duty to work; and introduce free education and the combination of education with work. ”

Note also that the language used by Keynes ‘euthanasia of the rentier class’ comming so soon after the USSR had anounced the ‘liquidation of the Kulaks as a class’, would have had an unquestionably sinister ring to it from the viewpoint of the rentiers.

“Marx held that a new type of state, politically free of control by the property-owning classes, was needed.”

No he didn’t! Marx argued for the dissolution of the state. The idea that you can have a state that is politically free of the property owning classes is alien to everything Marx believed was inherent in the state. As he says in the Critique of the Gotha Programme,

“The German Workers’ party — at least if it adopts the program — shows that its socialist ideas are not even skin-deep; in that, instead of treating existing society (and this holds good for any future one) as the basis of the existing state (or of the future state in the case of future society), it treats the state rather as an independent entity that possesses its own intellectual, ethical, and libertarian bases.”

For once I am tempted to agree with Boffy!

The state will not dissolve on its own accord, it can only wither away while under the conditions of ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’.

So at some point in the historical development the working class must have control of the state. The question then becomes how do they use this power.

The idea that the workers will not take control of the state seems at odds with the whole dialectical method.

The Gotha quote provided by Boffy is not the argument, this assumes the workers take control of the state permanently. No one is arguing that.

So Paul Cockshott raises reasonable questions.

To talk about “the state” in abstract is not just meaningless, it is misleading and dangerous for the reasons that Marx sets out in the Critique, in the 18th Brumaire, and in the Civil War in France, and that Lenin sets out in State and Revolution.

It begs the question “Who’s state?” It leaves the door open to the Lassalleans, Fabians and reformists like the old Militant Tendency (nationalise the 200 top monopolies) or the Stalinists to present the existing capitalist state as simply some kind of empty vessel that the workers can take hold of simply by winning an electoral majority.

It cannot, as Marx and Lenin set out clearly that state must be smashed.

“ All revolutions perfected this machine instead of breaking it. The parties, which alternately contended for domination, regarded the possession of this huge state structure as the chief spoils of the victor.

But under the absolute monarchy, during the first Revolution, and under Napoleon the bureaucracy was only the means of preparing the class rule of the bourgeoisie. Under the Restoration, under Louis Philippe, under the parliamentary republic, it was the instrument of the ruling class, however much it strove for power of its own.”

Chapter 7.

Lenin’s error, however, was to believe that it was possible to create some new workers state in place of this smashed bourgeois state, and to use it as the means of transforming society, of carrying through the social revolution after the political revolution. But, for the reasons Marx sets out such a venture is idealist, utopian and doomed to failure, as indeed it failed.

The social revolution must precede the political revolution as it always has done. Every time a political revolution has been launched pre-emptively, before the social revolution has been accomplished, those political revolutions have resulted in a falling back into Bonapartism – Cromwell, Napoleon, Louis Bonaparte, Stalin, Mao. Only on the basis of the transformed material conditions, productive and social relations, and the transformation of the revolutionary class that goes with it, and its development of new revolutionary organs of class power, can a new kind of class state come into existence.

For the working class, that is the basis of creating a new semi-state, which begins to wither away as soon as it comes into existence, as the working class turns its attention to the administration of things.

Well you started using the state in abstract terms before I did, I was responding to your usage of the state in this way.

If we look at the state concretely then there is no actual fixed way in which development occurs, in fact I am struggling to think of an example of where a semi state grew side by side with a dominant state and then supplanted it. So whether the state is smashed, or whether a semi state lives side by side with an existing state or whether the new dominant class take over the existing state depends on time and circumstance.

But for you there is only one way, only one actual existing condition and ironically not only is the state abstract in your method but everything is abstract!

Lenin’s error was not an error of theory, as you insist, but was a necessary step imposed by the conditions that the Bolsheviks were confronted with. This nicely gets me back to my criticism of your position, i.e. pure abstraction.

Not at all. As Marx did, I take any discussion of the state in the abstract to mean the current capitalist state. If we are talking about the state in the abstract, i.e. the state in different forms of society, then again, I take to mean, as Marx did, a class state, the state of the ruling class. Currently, the ruling class is the capitalist class, and so when anyone talks about “the state” nationalising the 200 top monopolies, or as Cockshott does, or as Michael has done in the past, talks about nationalising the banks, as an immediate solution, I take it in the only sense that any Marxist can take it, as meaning that the current capitalist state is bing appealed to to undertake such actions in the interests of workers.

My question, as was the question of Marx, Engels, Kautsky, Lenin and Trotsky to such propositions is – “Why would the capitalist state, the concentrated power of our class enemy undertake such an action on our behalf???”

Kautsky makes that clear in “The Road to Power, Trotsky in his pamphlet on Nationalisation and Workers Control, and Marx and Engels in numerous places, as does Lenin.

I am frankly amazed that you say “in fact I am struggling to think of an example of where a semi state grew side by side with a dominant state and then supplanted it.” The concept of a “semi-state” is only applicable for the conditions of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat discussed by marx, Engels, Lenin etc. It is only applicable under such conditions precisely because it represents the conditions under which classes themselves are being dissolved, and so where the need for a class state is also thereby dissolved.

Of course, under previous revolutionary conditions the issue of such a “semi-state” does not arise, precisely because it is not a question of dissolving class society, but of one ruling class supplanting another. As Marx says, it is only the working-class whose own liberation is at the same time the liberation of all of society, because no class exists beneath it.

But, I am also amazed at your comment for another reason, which is that if we ignore this question of the “semi-state”, but instead focus on the question of the process of transition, we do not have to look very far to see it even represented in Marx’s thought let alone in actual history. This is the process that Marx describes in the Communist Manifesto, for example.

“Each step in the development of the bourgeoisie was accompanied by a corresponding political advance of that class. An oppressed class under the sway of the feudal nobility, an armed and self-governing association in the medieval commune* : here independent urban republic (as in

Italy and Germany); there taxable “third estate” of the monarchy (as in France); afterwards, in the period of manufacturing proper, serving either the semi-feudal or the absolute monarchy as a counterpoise against the nobility, and, in fact, cornerstone of the great monarchies in general, the

bourgeoisie has at last, since the establishment of Modern Industry and of the world market, conquered for itself, in the modern representative State, exclusive political sway. The executive of the modern state is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie.”

In other words, it followed precisely this format that side by side with the growth of the economic and social power of the bourgeoisie went its own political development, its own organs of class power, based within its own political redoubts and bulwards in the towns and boroughs, where it was built up against the political power of the old feudal class., and was ultimately the basis upon which it launched its bid for state power against that old ruling class, along with its extension of its influence into the other organs of state power, such as the universities, where its greater wealth increasingly bought it influence, and was able to thereby create the dominant ideas that filled the heads of the state bureaucrats and functionaries.

As Marx states, there is no single instance in history whereby, “new dominant class take over the existing state”, and that is so because the nature of the state, as a class state, is there to serve the interests of the existing ruling class, not the revolutionary class that seeks to supplant it, and so it is not at all simply some kind of accident that no such take over of the existing state by a revolutionary class has occurred.

In fact, the experience of Lenin and the Russian Revolution proves the opposite. Lenin believed that it would be a relatively simple affair to take over the administrative functions of the state, as he sets out in State and Revolution. In reality, the Bolsheviks had to bring back the old capitalist managers of factories, the old Tsarist state officials, and the old Tsarist generals to administer the state, because the working class lacked both the ability and willingness to take on those functions. Those workers that had the ability and willingness were generally the better educated, more skilled workers such as the railway workers who were mostly Mensheviks, and so were prevented from taking on that function by the Bolsheviks. For example, Trotsky brought in the Militarisation of Labour in the Railways and other areas of Transport under his ministerial control.

I agree that Lenin and the Bolsheviks were forced to undertake such positions due to the reality of the conditions they faced after the revolution. The question then arises, as Engels sets out in “The Peasant War in Germany”, whether it was justified to undertake such a revolution in the first place, or whether it was a dangerous adventure, the costs of which we have paid the price for ever since.

I think you are correct to say that workers self action is crucial and that the bourgeois have sought to suppress workers self activity, and that the left should encourage workers autonomy.

“I take any discussion of the state in the abstract to mean the current capitalist state”

Well then why didn’t you make this assumption with me, rather than saying i was speaking in the abstract?!

We should view the state as a power centre that the workers cannot afford to ignore. Will that do?

“I take it in the only sense that any Marxist can take it, as meaning that the current capitalist state is bing appealed to to undertake such actions in the interests of workers.”

No, it is the political recognition that part of the revolutionary process includes taking over the power centre that is the state, in order to not only put down the enemy but also overrule any anti working class policies delivered by the state. The idea that the state is not some empty vessel does not preclude the idea that workers can use it for its own ends, just as previous revolutionaries have used the state apparatus for their own ends.

The belief that the failures of the Soviet system means we ditch the whole idea of taking state power is throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

“Why would the capitalist state, the concentrated power of our class enemy undertake such an action on our behalf”

The reason is because they will no longer be giving the orders!

“under previous revolutionary conditions the issue of such a “semi-state” does not arise, precisely because it is not a question of dissolving class society, but of one ruling class supplanting another”

But there will be a point when the working class is the ruling class; this precisely describes the dictatorship of the proletariat. So one ruling class will supplant another.

“As Marx says, it is only the working-class whose own liberation is at the same time the liberation of all of society, because no class exists beneath it.”

Where does Marx say that the bourgeois will simply dissolve on day one? I think the lesson of the Paris commune says otherwise.

“it followed precisely this format that side by side with the growth of the economic and social power of the bourgeoisie went its own political development, its own organs of class power, based within its own political redoubts and bulwards in the towns and boroughs, where it was built up against the political power of the old feudal class”

But it is the inner contradictions within capitalism that represents the development. So this means that capitalism’s tendency for concentration creates the forms of organisation that can be used for revolutionary purposes. Bringing large scale industry under public control or into big corporations being an example. I suspect your idea goes something like this, Co-operatives and other autonomous workers organisations develop alongside bourgeois institutions, a clash occurs between 2 states running side by side, the workers structures gain dominance over the bourgeois ones and hey presto we have socialism.

I do not think this is how Marx or Engels imagined it. They were what would be called today, nationalists, in that they imagined “production organized on the basis of common ownership by the nation of all means of production” and furthermore, to quote Engels, “To begin this reorganization tomorrow, but performing it gradually, seems to me quite feasible”

“I agree that Lenin and the Bolsheviks were forced to undertake such positions due to the reality of the conditions they faced after the revolution. The question then arises, as Engels sets out in “The Peasant War in Germany”, whether it was justified to undertake such a revolution in the first place, or whether it was a dangerous adventure, the costs of which we have paid the price for ever since.”

Now that is a different question, though it falls under the category of one of those “What if” questions that is purely academic. History does not play to a conductors baton. You can advise all you like but when events take over you have to take one side or the other. Every political complexity dissolves into this binary formation in the final analysis.

Edgar,

“Well then why didn’t you make this assumption with me, rather than saying i was speaking in the abstract?!”

I did! That’s the whole point. You referred to the state in the abstract, i.e. without qualifying its class nature, and the only way of interpreting that currently is to understand it to mean the present capitalist state. So, when you talk about workers now taking over the state, it can only mean taking over the existing capitalist state.

But, that is precisely what Marx, Engels, Lenin etc. say cannot be done, because it is necessary to smash that state, not try to take it over. The idea that workers can somehow take over the existing capitalist state, as though it were some empty vessel that just gets filled with different class content is what Lassalle and his followers, the Fabians and reformists, and various left reformists ever since including the Stalinists, and even those that call themselves Trotskyists like the Militant Tendency have put forward. It seeps into the propaganda of all sections of the left with their reformist proposals for that capitalist state to come to workers assistance via reformist policies for nationalisation.

“We should view the state as a power centre that the workers cannot afford to ignore. Will that do?”

If you mean we shouldn’t ignore it because its the concentrated power of our class enemy its “Executive Committee”, and “bodies of armed men, whose sole function is to keep the existing ruling class in power, and prevent the advance of workers, then yes, we shouldn’t ignore it. We should try to weaken it, and diminish it, at every opportunity, and seek to build up our own organs of self-government, and workers power in opposition to it, such as factory committees, neighbourhood committees, workers defence squads, workers militia and so on. If there are to be standing armies, then as Engels proposed, we should demand universal military conscription, so that all workers are armed and trained to defend themselves, and as Trotsky proposed in the Proletarian Military Policy, we should demand that such conscription be under trade union control.

“But there will be a point when the working class is the ruling class; this precisely describes the dictatorship of the proletariat. So one ruling class will supplant another.”

Which is why the question of a semi-state only arises at that point and has never been relevant for any previous social revolution.

“No, it is the political recognition that part of the revolutionary process includes taking over the power centre that is the state, in order to not only put down the enemy but also overrule any anti working class policies delivered by the state. The idea that the state is not some empty vessel does not preclude the idea that workers can use it for its own ends, just as previous revolutionaries have used the state apparatus for their own ends.”

But, that is precisely what Marx, Engels, lenin, Trotsky etc. show is impossible. A Workers State is a completely different animal to the existing state. It is not at all a matter of simply taking over some “power centre”, but of creating entirely new “power centres”, in the form of soviets, direct workers democracy, workers defence squads and militia etc. They arise in opposition to the existing power centre, ready to smash it and create something new.

Moreover, previous revolutionaries DID NOT use the existing state apparatus for their own ends. That is precisely the point that Marx describes in various places, and that Lenin sets out in State and Revolution. Each revolutionary class develops its own organs of state power in opposition to the existing state organs, and the culmination is usually a civil war. Cromwell did not use the existing state apparatus he smashed it, so did Robespierre etc.

“The belief that the failures of the Soviet system means we ditch the whole idea of taking state power is throwing the baby out with the bathwater.”

But I have not suggested that workers should not take state power. I have simply followed Marx and Lenin in stating that the state power that is taken cannot be the existing capitalist state power, cannot be based upon the idea of simply taking hold of some state apparatus. The idea you are putting forward is that of Lassalle, the Fabians and so on that Lenin dismantles in State and Revolution. The existing state apparatus must be smashed, and it must be replaced by a new workers state, whose whole nature arises in contradiction and opposition to the current state, and whose organs arise on the back of workers property, workers self-government, and workers democracy.

And, it is for that very reason that such a state, as Marx sets out in The Critique cannot simply be magicked into existence separate from the economic and social foundations for such a state, but must develop alongside them. You have stood Marx on his head.

“Where does Marx say that the bourgeois will simply dissolve on day one? I think the lesson of the Paris commune says otherwise.”

I agree, which is precisely why it is not possible to simply take hold of the existing state apparatus! You say that the capitalist state will no longer be giving the orders, but the experience of the Paris Commune of the Russian 1905 and 1917 Revolutions, and every other revolution in history shows that they will try! That is why those states have to be smashed. It is why a new state has to be developed in opposition to it, and that state can only arise out of the economic and social relations that workers develop in carrying through the social revolution. That new state arises on the back of those changes, it is not the means of bringing them about.

“I do not think this is how Marx or Engels imagined it. ”

It is exactly how they imagined it. That is why Marx talks in Capital about the process of extending co-operative production on a national scale being effected by the use of credit. Why would you do that gradually if all that was necessary was for some state to simply nationalise all capital? Moreover, both Marx and Engels attacked the idea of nationalisation. Both spoke about the transfer of existing nationalised property into the hands of the workers in those industries as a progressive move. Engels states,

“And Marx and I never doubted that in the transition to the full communist economy we will have to use the cooperative system as an intermediate stage on a large scale. It must only be so organised that society, initially the state, retains the ownership of the means of production so that the private interests of the cooperative vis-a-vis society as a whole cannot establish themselves.”

And that is AFTER workers have established the Dictatorship of the Proletariat! Prior to that, their position was described by their closest ally in the British labour Movement, Ernest Jones, who wrote to a Co-operative Conference, on behalf of the First International,

““Then what is the only salutary basis for co-operative industry? A NATIONAL one. All co-operation should be founded, not on isolated efforts, absorbing, if successful, vast riches to themselves, but on a national union which should distribute the national wealth. To make these associations secure and beneficial, you must make it their interest to assist each other, instead of competing with each other—you must give them UNITY OF ACTION, AND IDENTITY OF INTEREST.

To effect this, every local association should be the branch of a national one, and all profits, beyond a certain amount, should be paid into a national fund, for the purpose of opening fresh branches, and enabling the poorest to obtain land, establish stores, and otherwise apply their labour power, not only to their own advantage, but to that of the general body.

This is the vital point: are the profits to accumulate in the hands of isolated clubs, or are they to be devoted to the elevation of the entire people? Is the wealth to gather around local centres, or is it to be diffused by a distributive agency?”

And here too can be seen the manifestation of the idea of building workers property and workers self government independent of existing state structures, and of crating new structures that can form the basis of future workers power, because here it is the Co-operative Federation, the National Union that acts as the holding company, in the same way that Engels refers above to the sole function of a future state in that regard.

“They were what would be called today, nationalists, in that they imagined “production organized on the basis of common ownership by the nation of all means of production” and furthermore, to quote Engels, “To begin this reorganization tomorrow, but performing it gradually, seems to me quite feasible””

The idea that Marx and Engels were nationalists I have to say is bizarre. They believed socialism was only possible on an international scale. The comments about ““production organized on the basis of common ownership by the nation of all means of production” were ones they put forward in the Manifesto in their youth, and which they ditched in later life. In fact, a lot of Marx’s criticism of Lassalle and the Lassalleans is based upon the fact that they failed to move on from the ideas put forward in the Manifesto.

As Hal Draper sets out in “The Two Souls of Socialism” this idea about Marx as the statist planner is a concoction of the Second International reformists, and of the Stalinists, not to mention of his bourgeois opponents.

And of course, that process of transformation can begin straight away, as Engels rightly comments. Workers already are engaged in that process by establishing co-ops, and when workers go on from their to gain political power, instead of it being simply a Co-operative Federation carrying out the function Jones sets out, this Co-operative Federation itself becomes one of the administrative vehicles of the new semi-state, for carrying that process forward.

“Now that is a different question, though it falls under the category of one of those “What if” questions that is purely academic. History does not play to a conductors baton. You can advise all you like but when events take over you have to take one side or the other. Every political complexity dissolves into this binary formation in the final analysis.”

I agree, which is why I have always said that udner the circumstances I would have been supporting Lenin, especially as Trotsky points out in his History, that had the Bolsheviks not taken power there were other issues involved, such as the likelihood that Russia would have been carved up by imperialist powers, in the same way as happened with China.

But, we do have the benefit of hindsight, just as Engels did when he wrote the Peasant War in Germany, and that gives us the responsibility to use the benefit of that hindsight, and to draw the necessary lessons so as to try to avoid such mistakes in future.

The stagnation myth repeated here fails to account for the effect of deflation of manufactured goods and its effects on GDP measures.

The problem is how to account for growth in a period of falling prices, due to rising productivity? If you take the base year you overestimate growth, if you take the given year you underestimate it. So the BEA used chain measures;

Click to access ci1-9.pdf

Chain measures take the geometric mean of prices in two different years, which is in effect a modified form of the given year. This systematically underestimates growth in a period when prices are falling. So the ever present “crisis”, is nothing of the kind, but simply a statistical glitch caused by deflation.

Yeah, but the stagnation “myth” does account for the real increases in unemployment, the real declines in labor participation rates, the real increases in poverty in the US, the reductions in capital expenditures, the declining earnings (in the US at least), the growing number of defaults.etc etc etc.

Or perhaps you have another, more concrete, more accurate explanation?

Facts are stubborn things and must be reckoned with whether you like it or not Bill.

I think you’re being a bit unfair to Keynesians in their view of falling consumption. They have indeed, correctly or incorrectly, identified a cause for this decline–it’s the stagnant wages that result from being in a labor abundant economy. The increasingly globalized nature of the economy, the rise of manufacturing all over the globe, and the ease with which firms can relocate abroad puts downward pressure on wages. They believe this leads to a lack of demand and, thus, recession.

I agree with your take on things much more than the Keynesian version, but I think this is where they’re coming from. I know you and Andrew Kliman disagree with this take on wages but I just can’t see sustained wage growth in a labor abundant economy. So they do have a point.

Of course a surefire way to raise the rate of growth is to simply redefine what growth actually means and what is actually included. If you start to include categories like sex-industry earnings, illegal drug trade monies, and go on to include asset-price inflation in both property and stock markets, then, hey presto you have increased growth.

I agree. But there is a difference in the categories you include here. For Marx, sex industry earnings are definitely earnings, for example. In Theories of Surplus Value, he uses the earnings of prostitutes frequently to demonstrate against Smith and others that the performance of such labour service is as much value producing as the production of material commodities.

If the prostitute works for a capitalist brothel keeper, then as marx shows it not only produces value, but also surplus value, i.e. it is then also productive labour. The same is true with the drug trade. As Marx sets out in Capital I, a commodity does not have to comply with any moral or other requirements of its usefulness to society to be a commodity and to possess value, or surplus value. In fact, many economists have argued that the reason the GDP growth figures are so out of alignment with the growth of employment is that the methodology for measuring output is flawed, and large areas of value creation are simply being missed in the figures.

But the inflation of asset prices is a completely different matter. As marx demonstrates, an asset price, is purely fictitious. Capital, like land and labour has no value because none of them are the product of labour. As Marx says Labour does not have value, because it is value. Land has no value, and its price is merely capitalised rent.

Similarly, capital has no value, and its market price, the rate of interest, is determined by the interaction of supply and demand for money-capital. Asset prices such as the price of land, shares, bonds are then totally fictitious, and based upon the capitalised revenues those assets produce.

But, if you include the inflation of those asset prices, then during times such as the 1980’s-2000, when the largest rise in those asset prices occurred, you will end up with a totally distorted picture of changes in wealth, growth and profits, compared to the period after 2000.

Capital has no value?

Marx says that where?

In contradistinction to what he says Chapter 2 of Volume 3:

“The general formula of capital is M-C-M’. In other words, a sum of value is thrown into circulation to extract a larger sum out of it. The process which produces this larger sum is capitalist production. The process that realises it is circulation of capital. The capitalist does not produce a commodity for its own sake, nor for the sake of its use-value, or his personal consumption. The product in which the capitalist is really interested is not the palpable product itself, but the excess value of the product over the value of the capital consumed by it.”

So how can capital have a general formula, where value is thrown into circulation to extract a larger value, if capital has no value? How can the capitalist be interested in is “but the excess value of the product over the value of the capital consumed by it” if capital has no value?

What distorted abstract baloney from Boffy.

The issue comes when comparisons need to be made. Missing those changes in how things are measured can lead to incorrect conclusions about long term trends etc.