Back in 2002, current Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke made a speech in honour of monetarist economist, Milton Friedman on the occasion of his 90th birthday. Bernanke praised the work of Friedman and his colleague Anna Schwartz. Their seminal work (A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960) argued that the Great Depression of 1929-33 was caused by the bad decisions of the Federal Reserve. The Fed had let a credit bubble build up by allowing money supply to outstrip GDP growth and then the Fed cut money supply and raised interest rates too soon and engendered a banking crash and thus a deep depression. Bernanke ended his speech with the words: “What I take from their work is the idea that monetary forces, particularly if unleashed in a destabilizing direction, can be extremely powerful. The best thing that central bankers can do for the world is to avoid such crises by providing the economy with, in Milton Friedman’s words, a “stable monetary background”–for example as reflected in low and stable inflation. Let me end my talk by abusing slightly my status as an official representative of the Federal Reserve. I would like to say to Milton and Anna: Regarding the Great Depression. You’re right, we did it. We’re very sorry. But thanks to you, we won’t do it again.” http://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/speeches/2002/20021108/default.htm

Bernanke had famously argued in 1983 that bank failures in effect caused the Great Depression and this explains why he pushed for sufficient funding of bank bailouts, quantitative easing and other ‘unconventional’ monetary measures to avoid another depression arising from the Great Recession. The question is: is it right to claim that the Fed’s management of the money supply is crucial to causing or avoiding slumps as Friedman claimed and so plentiful supplies of credit or money can avoid banking collapses that engender slumps in the economy?

In a new paper (Bank failures and output during the Great Depression, http://www.nber.org/papers/w19418), Jeffrey Miron and Natalia Rigol do not think so. They found “little indication that bank failures exerted a substantial or sustained impact on output during this period.” They conclude that “At the broad-brush level, an impact of bank failures on output does not leap from the graphs. Industrial production fluctuated significantly during parts of the interwar period that experienced few bank failures. In particular, industrial production declined 28.8 percent over a span of fifteen months, from the cyclical peak in July, 1929 to the first wave of bank failures in November,1930. That magnitude decline – almost half the overall drop – makes it plausible that bank failures were partly a response to adverse economic conditions, whether or not failures contributed to output losses.” In other words, the Great Depression kicked off with a fall in industrial output which then led to bank failures that exacerbated the crisis, but not vice versa.

What this suggests is that bailing out the banks would also do nothing to end a capitalist slump but simply preserve the interests of the financial sector. And also that pumping money into the banks through measures like QE would have little effect on restoring investment and industrial output. After all, the strategy has proved pretty abysmal at doing anything other than expanding the narrowest measures of money supply, or for that matter propping up banks and asset markets. That is because bank lending is demand-driven and when the demand for investment is not there, there is no demand for bank lending. It is not really a supply issue (see http://www.clevelandfed.org/research/commentary/2013/2013-10.cfm). That means bank failures are more a symptom rather than a cause of crises.

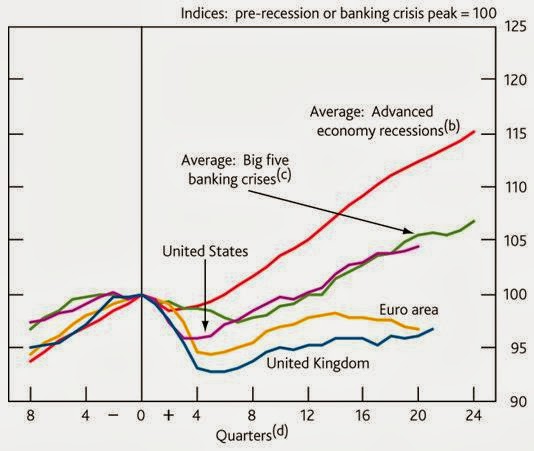

That is also suggested by a comparison of the recovery from the Great Recession by the major capitalist economies. In the graph below (produced by the Bank of England), we can see that recovery from recessions on average is achieved within four quarters (red line). If a banking crisis is also involved, then it takes up to 12 quarters (green line). But the Great Recession has been much worse, with only the US getting anywhere near an average recovery (purple line), while the Eurozone and the UK in particular are still way behind.

Tony Norfield, at his excellent blog (http://economicsofimperialism.blogspot.co.uk/) and in a recent paper (Tony Norfield on derivatives and the crisis), explains well why banking crises and, in particular, the global financial crash, made the Great Recession worse than others, but is not the main cause for the slump. “The rôle of derivatives in the latest crisis was to help extend the speculative boom. In that sense, they made the crisis worse than it might otherwise have been, especially since the deals spread far beyond the US, overcoming any more local barriers. However, derivatives did not cause the crisis, they merely gave it a peculiar intensity and financial form. Low growth and low profitability were the reasons for the boom in derivatives-trading and ‘financial innovation’. Alongside other aspects of the credit-system, derivatives can help promote capital-accumulation by saving companies transaction-costs, by giving the impression that risks are lower than in reality, by appearing to represent wealth that can be used as collateral for loans and by generating recorded profits based on speculation-driven prices. A blip in the system, a loan that does not get repaid as expected, can then trigger a financial collapse as it calls into question the assumptions behind a myriad of other deals. This is what is really meant by a ‘lack of confidence’ in financial markets: a fear that the expected values are illusory. The financial collapse impacts upon the ‘real’ economy, as credit is withdrawn and the funds lent by banks dry up, even to previously viable companies. The end-result is a worse crisis, when it finally occurs.”

A banking crisis can make a recession worse but also make a recovery weaker. There is a lot of evidence that the root of Japan’s lacklustre performance after its credit crunch and banking crisis in 1989 was the failure to ‘cleanse’ the banks of an overhang of debt. The bad debt problem was finally dealt with by two government-backed agencies which were established to dispose of soured loans and restructure troubled corporate borrowers, but not until the late 1990s.

In a previous post (13/02/14/japans-lost-decades-unpacked-and-repacked/), I showed how Japan’s rate of profit was raised during the 1980s by a massive credit and property boom. But that could not last. After the great credit bubble burst in 1989, the average rate of profit in the Japanese economy fell nearly 20% during the 1990s. But from 1998 to 2007, it rose nearly 30%. During the 1990s, the corporate sector deleveraged by 15%, laying the basis for profitability to recover. Average real GDP growth eventually came back (relatively) because Japanese corporates had written off old capital enough and Japanese banks were finally in better shape to lend again – of course only after a lost decade of income and jobs for its population in the 1990s, culminating in the dire deflationary slump of 1998.

Capitalist economic recovery will only take place if capital (both tangible and fictitious) is written down and profitability is sufficiently restored. Pumping in more money Bernanke-style merely delays that process and thus produces a weak and slow recovery at best. But Bernanke persists in order to try and avoid a deflationary slump as in the 1930s.

Bernanke’s mistake, as I set out here is that he fails to distinguish between different conjunctures, and thereby believes that a policy prescription that can work in once situation will work in another.

1929 was not the start of the crisis. The Long Wave Boom had ended around 1914, and Europe was in a period of downturn from 1921 onwards. The US did well during that period for specific reasons, but 1929, and the Depression of the next 4 years meant they were simply catching up with Europe.

Easy money could not have resolved that situation, because as you say demand for Capital during this period was demand led, and without the potential for sharply rising demand there was no basis for large scale investment in most industries.

However, its notable that by the mid to late 30’s, in Britain, the Long Wave cycle was turning, and new industries such as car production, in the Midlands, consumer electronics production in the South-East etc. was already starting to be developed, with relatively high wages for the workers employed in it. Along with that development went the development of new building techniques that started to make houses, in suburban estates, affordable for the first-time, for these more highly paid workers, and all of the peripheral activity that goes with it.

Neither Keynesian nor Monetarist solutions could have acted in the 1920’s and 30’s to provide any sustainable solution, until all of these new industries were developed to provide a basis for profitable investment. It was there development in the post war Long Wave Boom tht meant Keynesian fiscal stimulus could act to cut short recessions.

But, as Marx and Engels set out in Volume III in relation to the financial crises of 1847 and 1857, resulting from the 1844 Bank Act, not all crises are economic. Financial crises can be caused by bad legislation, and by an inadequate supply of money in circulation, which in turn prevents the circulation of commodities. As Engels describes both those crises were quickly ended, and rapid economic development resumed, simply by putting the necessary additional liquidity into circulation.

That was the situation in 2007-8, as banks withdrew liquidity during the credit crunch. Resolving it with liquidity was the right thing to do, but the continuation of that liquidity has made matters worse. It has fuelled asset price bubbles that undermine economic recovery, because they raise the value of labour-power, create uncertainty, and encourage monetised surplus value, to be used for speculation, where high capital gains can be made, rather than in productive investment.

Where has the value of labor power been raised?

And..where has it been raised by excess liquidity? Indeed, if the thrust of austerity is to drive the total wage bill below the cost of reproduction of the class as a whole (and obviously I think that is the point) how exactly do the long-term refinancing operations of the ECB, Fed, drive up the value of labor power?

“Capitalist economic recovery will only take place if capital (both tangible and fictitious) is written down and profitability is sufficiently restored. Pumping in more money Bernanke-style merely delays that process and thus produces a weak and slow recovery at best”.

And yet as you demonstrate very clearly, it is the USA of all the Western powers that has recovered fastest. Hardly a critique of QE then.

If QE is measured by the increase in central bank assets since the beginning of 2008, then the Fed’s balance sheet has risen 15.4% pts of GDP, the BoJ by 20.9% pts, the BoE by 18.9% pts and the ECB by 10% pts. In percentage increase since 2008, the UK’s BoE had the largest rise by far and the UK economy the weakest recovery. The Fed’s much publicised QE policy has been less than the BoE and the BoJ, so the relative outperformance of the US economy cannot be explained by QE. Hardly a vindication of QE then.

Well indeed, as you demonstrate QE has very significantly offset the costs of the recession for these economies. It nonetheless, remains a stretch to assert that it is the *reason* for the sluggish recovery. QE mainly works by lowering taxes – it means that the state does not have to raise the revenue garnered from QE through taxation – and so increases real profits and lowers wage costs, it also marginally reduces interest rates by lowering government demand for capital.

The recovery has not been sluggish for the capitalists, who have seen profits double over the last five years.

The relatively slow growth in national income since the crisis, is in large part due to a savage retrenchment in social expenditure, that is, it is a result of a political decision by the capitalists to take advantage of the weakness of the labour movement, to reduce the size of the state.

Bill– I think it was you who explained the recovery in the US very well and very succinctly:

“With a supine labour movement, and profits rising due to falling wages, why invest?”

That’s exactly correct, QE, interest rates, liquidity supplies have have not been the source of the recovery.

Some tangible assets have been written off (not enough, IMO, to reverse what is a recurring trend) and in the US the asset-backed securities have been devalued much more effectively than in the EU. EU financial institutions still carries a trillion or so euros of non-performing “assets” on its dance card, the dance being the zombie jamboree of course.

Re Japan, I think the failure in it’s recovery since 1989 has been its inability or unwillingness to accomplish what say Germany did after 2002 with the “Agenda 2010” and what the US has made an art-form of since 1974– “low-balling” the working class.

That’s right and some of us have been saying it for ages. Most agree but then feel the need to look for other reasons why investment is low. Cutting real wages is relative, not absolute surplus value (in my view!), and hence ‘closer’ to the classic way of increasing relative surplus value through investment/productivity. A perfectly legitimate method for capitalists.

An article by Martin Wolf in the FT a while back looked at the reasons behind low – or falling – productivity in the UK. One was substituting labour for capital as wages are fall!

You mean Tony *Norfield* not Northfield.

Phil

Phil

Whoops – it is a sign of senility! How could I do that to Tony? Thanks.