Last weekend, I delivered a keynote lecture to economics students at Britain’s Open University on their Economics Day. This is a transcript of my presentation.

Today I have been asked to speak on the topic of: Why ‘real world economics’ matters? That title begs a few questions: What is real world economics? And this implies that there is economics that is not about the real world. And if there is real world economics, what can it contribute to making a better world for us all?

Real world economics should be about understanding what is happening in the world around us: what causes inflation, unemployment, poverty, inequality, climate change etc. And what are the economic policy answers. But there is a problem. What I call mainstream economics does not discuss or deal with these real world issues very well.

One example directly involving this very building springs to mind. Back in the depth of what came to be called the Great Recession of 2008-9 when all the major economies were suffering a sharp and deep fall in national output, employment and average incomes, after a humungous collapse in the banking and financial systems, Queen Elizabeth visited the London School of Economics.

As she stepped into this very building, she asked the gathering of eminent economists who met her: “Why did no one see it coming?” In other words, she asked why no one had predicted the financial collapse and the ensuing slump, the worst since the 1930s depression years. The eminent economists were nonplussed by the Queen’s question about the real world. It took them three months before they responded – in a published three-page letter to the Queen.

I quote: “Everyone seemed to be doing their own job properly on its own merit. And according to standard measures of success, they were often doing it well. The failure was to see how collectively this added up to a series of interconnected imbalances over which no single authority had jurisdiction.” I think the economists were saying that their theories seemed to be fine but then lots of different things that they knew about somehow all came together in a perfect storm to create the crash and they could not have foreseen that.

Six months later the Queen visited the Bank of England and one of the Bank’s top financial policy experts stopped the Queen to say he would like to answer the question she first posed to those economists at the LSE. He told the Queen that financial crises were a bit like earthquakes and flu pandemics in being rare and difficult to predict and reassured her that the staff at the Bank were there to help prevent another one. Prince Philip did not miss his opportunity: “so is there another one coming?” No answer.

But here is my point. It’s not just that the economists didn’t notice it coming ‘out of the blue’ like an asteroid hitting the earth, a shock to a perfectly working economic system. Their theories assumed away the possibility entirely.

Robert Lucas is an eminent mainstream economist, indeed a Nobel prize winner for economics. In 2003, some five years before the global financial crash he pronounced that “macroeconomics has succeeded: Its central problem of depression prevention has been solved, for all practical purposes, and has in fact been solved for many decades.”

Eugene Fama is another Nobel prize winner in economics. His prize is for showing that markets work efficiently and, as long as you and me and everybody has enough information about what is going on, then the market will ensure full employment, steady growth and rising incomes for all. This is called the Efficient Markets Hypothesis (EMH). After the Great Recession, Fama was asked what went wrong. He replied, “We don’t know what causes recessions. We’ve never known. Debates go on to this day about what caused the Great Depression. Economics is not very good at explaining swings in economic activity”.

Up to now I have talked about one economics event and one strand of explanation: what I have called mainstream economics and its failure to forecast or deal with that event, i.e. global financial collapse of banks and a deep contraction in employment and incomes globally. A real problem but with no answer from the mainstream. But that poses the question that if mainstream market economics cannot explain the real world very well, then we need new theories to guide our policy decisions.

And there are other theories. Indeed, we can categorise economics into various schools, with the main division between ‘mainstream’ and ‘heterodox’. In the mainstream, we have two great sub-divisions. The first is called the neoclassical school. This school starts from a basic assumption that a ‘free market’ ie. without interference or imperfections caused by monopolies or trade unions or the government, will deliver harmonious economic improvement in what is called a ‘general equilibrium’. As one neoclassical economist once put it: ‘the market economy is like a calm lake or pool. Sometimes a rock or stone can disturb it, a shock to the calm environment, but eventually if those interferences stop, the ripples in the pool will subside and the pool will be calm again’.

Within the mainstream, there is also the Keynesian school, named after the theories of John Maynard Keynes, the great British 20th century economist. Keynesian theory rejects the equilibrium idea of the calm pool of the neoclassical school. The Keynesians think the neoclassical model is not ‘real world’ economics. The Keynesians argue that market economies sometimes get into ‘disequilibrium’ leading to depressions and unemployment, which economies do not get out of unless governments intervene with measures including printing more money or increasing government spending to restore equilibrium.

But both the neoclassical and Keynesian schools agree on one thing: that a market-based system is the only viable form of economy. It’s just that one school thinks that ‘harmonious’ growth can be achieved by a free market without interference and the other thinks government and central banks must intervene to correct any disequilibrium.

But mainstream economics starts from an assumption that it has not proved – namely that a market economy where companies employ people like us to produce goods and services to sell on a market for money – and more importantly for profits for the owners and shareholders of those companies – is the only way to organize the production and distribution of things that we humans need.

But the market economy has not always existed – indeed it has been around for only about 250 years. Before that there were feudal economies where peasants or serfs worked the land for their masters who consumed the produce. That system was around for over 1000 years. Before that there were slave economies where people captured in wars were forced to work for their slave owners – that system was around for thousands of years.

I make this point because we should be aware that how economies are run now has not always been here and may not last as the best way to meet the needs of humanity. Indeed, in my view, the market economy shows significant signs of failing to do so. So there may be other ways of economic organization.

As such, there are economists who have serious criticisms of mainstream market economics. There is what we can call the heterodox schools of economics – the term meaning what it says, outside the orthodox mainstream. Within this broad strand, these economists highlight the irrational behaviour of markets and the inherent instability of the market economy. They include the Marxist school which argues the market economy will always have crises that cannot be resolved by the market and so the market economy (called capitalism by Marxists) needs to be replaced by a planned economy based on common ownership of all producers.

The heterodox school is very critical of the mainstream. Indeed, almost exactly six years ago, leading heterodox economists held a seminar right here at the LSE on the state of mainstream economics, as taught in the universities. They kicked this off by nailing a poster with 33 theses critiquing mainstream economics to the door of this building. (You can google it). It was the 500th anniversary of when Martin Luther nailed his 95 theses to the Castle Church, Wittenberg which provoked the beginning of the Protestant reformation against the ‘one true religion’ of Catholicism.

The heterodox economists were telling us that mainstream economics was like Catholicism and must be protested against as Luther did back in 1517. As they put it, “Economics is broken. From climate change to inequality, mainstream (neoclassical) economics has not provided the solutions to the problems we face and yet it is still dominant in government, academia and other economic institutions. It is time for a new economics.”

What should that new economics be? Recently, Benoît Cœuré, a leading French member of the Executive Board of the European Central Bank, delivered an address just like I am doing now to you, to economics students at the Paris School of Economics, if you like, the sister university to the LSE. Cœuré told his student audience that “economics is a social science. Models will not take away the burden and responsibility of making judgements. Economics involves much trial and error – you have to take decisions in the fog when you can barely see your hand in front of your face. This makes our profession exciting!”

For me, economics is a science – if a social science dealing with humans, not a physical science. As a science, it requires scientific method. For me, that means you start with a hypothesis that has realistic assumptions that have been ‘abstracted’ from reality and then construct a model or set of laws that can be tested against evidence. The model can use mathematics to refine its precision, but eventually the evidence decides. In my view, like physicists and astronomers, economists too must be able to develop theories about the economies in the real world and test them empirically so that we can make predictions and hopefully avoid the economic crises that modern economies have on a regular basis.

Up to now, I have discussed the big events like the Great Recession and the contribution or failure of mainstream economics to forecast or explain them or provide effective economic policies to remedy them and avoid more in the future. But much of mainstream economics is not about these big events. Benoit Cœuré in his Paris lecture dismissed the criticism that economists failed to predict the outbreak of the financial crisis. “This criticism is nonsense. Do we expect physicians to predict illnesses? We don’t, of course. But we expect them to help us cure illnesses. Economists should do the same.” So it’s not the job of economics to forecast or predict but to develop policies to cure any messes that emerge.

This is a common theme among economists. Another recent Nobel prize winner, Esther Duflo, reckoned economists should give up on the big ideas and instead just solve problems like plumbers “lay the pipes and fix the leaks”. Economists were more like engineers than physicists. Keynes made a similar point: that economists should be like dentists – sorting out troublesome teething problems so that capitalism can then run smoothly.

Duflo reckons the analogy of plumbers means that pure scientific method of analysing cause and effect was less important than practical fixes. So economists should be more like doctors than medical researchers. Plumbers, dentists, engineers, doctors – but not, it seems, social scientists.

But are doctors all that matter in human health? Actually, improved doctoral skills in treating patients once they have become ill comes from scientific discovery about diseases, biology and the environment. Successful drugs and medical practices are the result of learning what the cause of the illness is.

In medieval times, doctors applied all sorts of useless and dangerous treatments (leeches etc) because they did not know that about ‘germs’ (bacteria or viruses). Cholera was eventually abated by a geographical study in London showing it was prevalent near bad drinking wells. Malaria and smallpox were resolved by discovering the carriers of the bacteria in various animals. Treatments by doctors then followed.

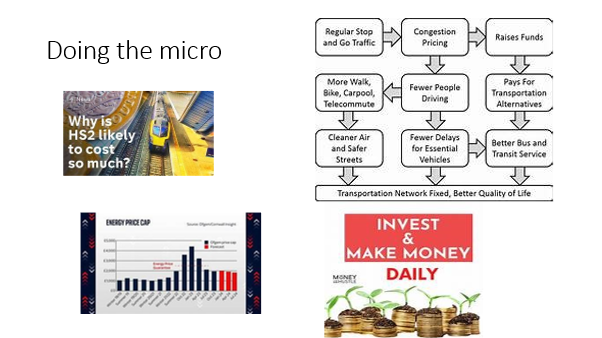

Of course, that does not mean economics is not about understanding an economy at micro or small levels and coming up with policies to change things for the better – the right taxes to raise funds for government programmes and achieve better equality; suitable price caps to curb energy prices; the right congestion charges to reduce fossil fuel traffic, clear cost benefit analysis to gauge whether the HS2 rail should be built or not. This is also part of economics.

Indeed, this is the sort of economics and policy making that most economists do and probably how you would make a living if and when you graduate and stay in economics. And you could do well. Couere explained to his Paris students that becoming an economist was a great thing to do and paid well. “For many, a master’s degree is a natural step towards a PhD. And a PhD is essentially a promise of employment. In the United States, for example, the unemployment rate for PhD economists is about 0.8%, the lowest among all sciences. Not a bad place to start from.” But said Couere, the money was less important because “your PhD should be fuelled by your passion and your love for research rather than by hopes of earning more money.”

I am sure that is the case for all of you too. However, I must be blunt here. Cœuré’s experience in the public sector may be different from those of us who have worked in the private sector. Having worked in the private sector, in banks and other financial institutions in my ‘career’, economic policy advice and making things better for all is not the target, but instead it is ‘how to make money’. Economics there is geared to either corporate strategy for profits in production and trade or to investment strategy for profits in financial speculation.

In my view, real world economics must look at the ‘big picture’. Economists should not be just doctors but social scientists, or more accurately they should develop an economics that recognises the wider social forces that drive economic models. That is called political economy, mostly not taught in universities. Let me remind you of some of the big picture economic issues that will affect us all much more than anything like whether the HS2 rail line is built or income taxes should be raised or reduced.

First, there is global warming and climate change. The international Cop28 is meeting in Dubai right now on how to reduce greenhouse gas emissions – what is needed is a 43% reduction in emissions by the end of this decade if the world is to avoid an average increase in global temperature more than 2C above pre-industrial levels.

What are the economic theories and policies that can achieve that reduction? It is worrying to know as the LSE’s own Nicholas Stern, the world’s leading climate economist, has noted: “Economics has contributed disturbingly little to discussions about climate change. As one example, the most prestigious mainstream Quarterly Journal of Economics, currently the most-cited journal in the field of economics, has never published an article on climate change!”

Then there is the issue of global poverty and rising inequality of wealth and income between nations around the world and within nations. According to the World Bank, there are around 3.65bn people living on less than $6.85 a day. There are over 700m people facing daily hunger. There are over 3bn people not eating a healthy diet and so getting ill, obese, or even wasted. Is it morally right or even good economics that the top 1% of the world’s adults own nearly 50% of all the personal wealth in the world while the bottom 50% have only 1%? What can we do about this?

Angus Deaton is a British Nobel prize winner in economics and an expert on poverty economics, working in America. In a recent book, Deaton angrily said that “mainstream economists deliberately ignore rising levels of inequality and the horrendous impact of poverty, claiming that this is not the business of economics. …. “there is this very strong libertarian belief that inequality is not a proper area of study for economists. Even if you were to worry about inequality, it would be best if you just kept quiet and lived with it.”

Then there is the technology of the 21st century: robots, automation, artificial intelligence, in particular the emergence of super-intelligent language learning models (LLMs). Have you used LLMs like ChatGPT yet for leisure – but hopefully not for writing automatic dissertations for your professors? Apparently, four out of five British teenagers are using it for school work, according to Ofcom, the technology regulator. What does all this mean for your future jobs when you graduate – will AI have replaced you before you graduate? Some economists estimate that 300m jobs will go globally. Here is another vital area for real world economics.

I finish by saying to you all: remember that there is a world out there beyond supply and demand curves and mathematical formulae.

Economics and economists should not be sucked into just being like dentists fixing teeth, but also use their skills and the scientific method to understand the big picture and so help to make a better world for all. Then perhaps we can avoid being visited by King Charles at some time in future and have him repeat what Queen Elizabeth said: “why did you not see that coming?”

Well said. I am reminded of an eminent radical economist of technology who nevertheless stuck to deterministic equilibrium models and when I asked him why, he replied it was the only way to be published.

Science or not, all the evidence points to the direction that Economics is in intellectual decline. The turning point was 2008. If we analyze the historic of Riksbank “Nobel” Prize winners, we can see that, up to 2008-2010, the committee tended to award “big theory” economists, i.e. theorists. After the 2008 crisis, we can see a pattern of awarding the so-called experimentalists or empiricists, i.e. economists who dedicated their careers to seemingly objective, empirically demonstrable hypotheses, with no ambition whatsoever to understand the observable universe (of which Duflo and her husband are only the stereotype).

Intellectual declines are inevitable in History, and Economics is not the first case and will not be the last. Some sciences become extinct simply because they achieved their ultimate objective: Philosophy essentially ceased to exist after Marx for the simple fact he depleted all of its possibilities. Nowadays, what we call “philosophers” are essentially specialists in metaphysics (which often degenerate into Theology) and in Ethics or Aesthetics. As Marx has also become the East’s (the Chinese branch) main philosopher, that also means Philosophy there is essentially extinct.

Economics started to decline because capitalism started to decline. Since the postwar, capitalism has to live side by side with a new, superior, mode of production: socialism. This reality led to what Edward Carr called “the political era of capitalism”, in opposition to the “economic era” (Carr was a liberal, not a communist). This is why the brilliant political (classical) economists (from Ferguson to Ricardo) gave way to the imbecilic, vulgar economists (future neoclassical or orthodox). And, since rock bottom has a basement, it declined once more after 2008.

From a historical point of view, there is little doubt capitalism is in decline. It is hard to underestimate the ideological fervor and euphoria of the End of History Era (1992-2008). John Lewis Gaddis, the American historian of the Cold War, published an article in 1990 (!!), stating that the only challenge humanity had now that the USSR was clearly collapsing, was to mop up the remaining barbarians of the Middle East or any other remains of religious extremism; Time Magazine published a huge article in 1992 predicting how humanity would look like in the 21st Century, and it basically stated that the only big tectonic change would be the rise of the European Union, which would form a huge North Atlantic civilization that would forever rule humanity. Historical revisionism in the West was rampant: what was a historical inevitability — the USSR — suddenly became an abortion of History; Sheila Fitzpatrick, in her 1990s book about the Russian Revolution, stated so, and went further, stating that all the revolution in History were abortions.

The intellectual decline in the West was not circumscribed to the Humanities. Physics started to decline after 1979, a decline that was confirmed and turned inexorable by the rise of String Theory — a decline that continues unstopped nowadays. Medicine stopped progressing many decades ago, nowadays only progressing at a vegetative pace, and in just a few areas. Pharmaceutics has degenerated into pure abstract statistics. Contrary to Humanities, the hard sciences are mainly a victim of their own success: the discoveries possible by particle accelerators have already been done, so experimental physics could not keep up with theoretical physics, and the limits of human body have done the same with medicine/biological sciences. The limits of steel, titanium, aluminum, lithium, silicon, gold, petroleum etc. and the failure to develop nuclear fusion and room temperature superconductors have more or less done the same with engineering.

If capitalism in the West is not able to ignite a new Kondratiev Cycle, expect the process of its intellectual decline to continue unabated and at an accelerated pace.

Speaking of current “real world economics,” another area that mainstream economists tragically ignore is the question of war. Yes, 1st-year textbooks in university will include in their introductions a few paragraphs about the “guns-or-butter” dilemma, but discussion will certainly not progress much beyond that. Where is the analysis of the “economic efficiency” of the military in academia? For example, how many jobs does investment in new fighter jets produce as compared to the NHS? [hint: many, many fewer…] And that is just one narrow, limited question. There are many more, “big” questions to examine, but economists seem not to be interested in them, even when a government publishes its annual budget: rarely does anyone report on the size of the military budget, for example. [exception: the US media do address this in their reporting of almost $1 bn spent annually, but it’s NEVER a topic of debate or discussion by either political party; it’s presented as just a fact.]

With that in mind, perhaps an examination of a current war might be instructive. Namely (you guessed it) the Israel-Gaza war. Below is an interview (starting at minute 3:15 to minute 10:30) with Ayal Winter, an economics professor at Lancaster University in the UK and at the Hebrew University in Israel, on Al-Jazeera about a week ago.

He seems to be saying that despite the fact that this war will be “very costly” (about 200 bn Shekels, or $50 bn USD), it’s not a big part of Israel’s GDP. He will admit that the tech sector, however, is hard hit b/c many employees in that sector are reservists who have been called up for service. And in the agriculture sector, many foreign workers have left Israel, but there is a well-developed volunteer programme in place. Moreover, he says that the reconstruction will spur the economy (Keynsianism) after the war… Overall, he says that the negative war economy prognosis is not so “grim.” He of course doesn’t mention HOW Israel is able to sustain what I would call a permanent war economy [i.e. US subsidies], but these are interesting claims to examine, all in line with this blog posting about “real world economics.” Where are the other discussions about these questions?

Also – the 2nd half of the report discusses the oil reserves off the coast of Gaza, which of course, raises other interesting questions about the role of imperialism and the economy, and which, of course, mainstream economists are silent on…

Any thoughts?

Sean

“… OIL RESERVES off the coast of Gaza …” -> Are you worried about oil? YOU DO WELL: “Global conventional crude oil production peaked in 2008 at 69.5 mb/d and has since fallen by around 2.5 mb/d.” (Page 45 of the World Energy Outlook 2018 by the International Energy Agency.) And speaking about the profession there was a hell of an economist once in England: “The Coal Question; An Inquiry Concerning the Progress of the Nation, and the Probable Exhaustion of Our Coal Mines” by William Stanley Jevons was written in 1865 to explore the implications of Britain’s reliance on coal. Had he been invited to “lecture” young future colleagues I bet he wouldn’t have missed the opportunity to remark the real source of nowadays CIVILIZATION, FOSSIL FUELS, and the mortal danger implied in their depletion. What are we going to do? Time is running out. The end is nigh! The end is nigh!

Of course I agree with the general notion that economics needs to deal with the real world and that demands understanding how society works.

The prevailing idea that economics can be like plumbing or dentistry or engineering is a two-fold error I think. First, in those skills the basic science is settled. In social science, the apologetic function of the academy means no questions can be deemed settled. (Hence the inclusion of seminaries in higher “education.”)

Second, there is the very notion that economics is a physical science, a kind of direct confrontation with the scarcity imposed by nature and the natural chaos and unpredictability of nature is doubly untrue. Economics so rarely engages with nature that as so correctly highlighted above, that it doesn’t address climate change. Very little of the actual technology of production and distribution is concretely studies. In one sense, this is proper, as “economics,” if it is to be anything should be a social science, just as the original was “political economy.” Except of course economics doesn’t do that either. It doesn’t even engage with economic geography and history consistently, much less systematically. Economics pretends that its version of society really is the expression of necessity, as in, natural law, not social arrangements that will inevitably change (and in principle amenable to human efforts.)

Few would be so crude as to say so plainly, but effectively the purported laws of economics are the laws of nature and human nature *and therefore the will of God.* The corollary is simple enough: Acts of God cannot be predicted. Hence the airy dismissal by the likes of Coeure of the many glaring failures of economics passes for sense instead of nonsense. Such an essential question of what genuine equilibrium looks like in the physical world, whether its possible and what social arrangements are incompatible with it or even what kind must be required can’t even be asked.

Being compulsive though, there are quibbles. It seems to me that Keynes held that real world national economies could get into a false equilibrium. Both neoclassical and Keynesian theories assume there really is a true equilibrium. So far as I know, it is only the Marxian critique of political economy which holds that economic crisis is a necessary phase in the workings of the capitalist system. In this view capitalist political economies are not equilibrium systems. And the demonstration that for instance a proportionality between production good and consumption good sectors is necessary to a crisis-free expanded reproduction is an impossible condition given the systemic need to accumulate capital, a systemic requirement not an individual whim. (Later developments seem to suggest that another way of phrasing this is, all spheres of production must have the same organic composition of labor, which really does seem like a physical impossibility to me, unlike von Hayek’s notion of “scarcity.”)

So I’m not sure how different other sets of heterodox economists are fundamentally different. Sometimes it seems is economics’ Hegel, his philosophy died with him and nobody since can agree. Nor am I sure how many people are ready to entertain the idea at all. It’s true I suppose the geologic time scale powerfully suggests this. But as I say, genuinely confronting nature is *not* a part of economics.

“But the market economy has not always existed – indeed it has been around for only about 250 years. Before that there were feudal economies where peasants or serfs worked the land for their masters who consumed the produce. That system was around for over 1000 years. Before that there were slave economies where people captured in wars were forced to work for their slave owners – that system was around for thousands of years.”

If market economy means that transfer of products is conducted by exchange for “money” or other commodities, rather than by direct compulsion or by prices set by custom or some authority like a producers’ guild or monarch, then market economy has been around much, much longer. The dominance of world trade by this kind of pricing may be closer to 250 years old, but serfdom existed in the world till 150 years ago and so did slavery. One of the funniest things, in a gallows humor sort of way, is the notion that government is the problem because it distorts the market. World economy has never been dominated by a single government in the sense meant. Thus according to that principle the world economy has never been distorted by the state. Yet, the world economy has always been one of recurrent crises! But, while Lucy may have some ‘splainin’ to do, economists apparently do not.

“So far as I know, it is only the Marxian critique of political economy which holds that economic crisis is a necessary phase in the workings of the capitalist system. In this view capitalist political economies are not equilibrium systems. And the demonstration that for instance a proportionality between production good and consumption good sectors is necessary to a crisis-free expanded reproduction is an impossible condition given the systemic need to accumulate capital, a systemic requirement not an individual whim.”

That is correct. Capitalism is a mode of continuous disequilibrium where equilibrium, like the coincidence between value and price, can occur, but occurs randomly. Marx himself in Vol 2 when producing his numerous iterations on the circuits of reproduction uses the term “equilibrium” as if that is something capital seeks, or must seek, when in fact all the processes of the development of capitalism manifest disequilibrium: concentration and centralization of production, the establishment of a general rate of profit, the migration of capitals as both product and producer of that general rate– and all of these originate in the “primal disequilibrium,” between production and consumption in that workers must not be compensated and cannot “buy back” the value produced for surplus value to exist and for capital to accumulate.

Double-checking for my error, I must add, to clarify, in the process of circulation of commodities and the attendant movement of capitals, the socially necessary abstract labor time is worked out in practice, approximated in the test of exchange. In circulation conceived as a moment, the laws of motion or dynamics of capital tend to move around a kind of center of mass, where competition drives all profit rates to zero, and expanded reproduction ends as accumulation of capital ceases. The pursuit of realized surplus value in the forms of differential rents, profits of various types and interest is the motor. (Individual capitalists have this motive in different degrees but those who deviate too far from the norm lose their capital and their relevance to the workings of the system. Individual motives are imposed responses to the real position in the system of production/expanded reproduction.) Since however the system is in disequilibrium and only one moment is moving toward equilibrium, until this impossible Nirvana of capital (where surplus value and profit and capital and wages are as nothing as the Buddha) the process of circulation shows how profits can be realized in one phase of the whole process of production, reproduction and expanded reproduction. Speaking of equilibrium when addressing one moment of the total process is appropriate, likely enough practically necessary. So I do not agree that Marx is wrong to do so. In particular, so far as I can tell, most forms of underconsumption are ruled out by this analysis. So I do not think Marx was wrong in his terminology in volume two.

But, again, volume one addresses the moment of production showing the origin of profit in surplus value and the accumulation of capital, which is intrinsically a disequilibrium process, where capital is not and cannot be static. Capital’s law of motion or dynamic is toward increase and in the end, only increase. That’s why there was a whole historical epoch of progressive capitalism (1517 to 1917?) Volume two addresses the moment of realization of profits through exchange of commodities at their value despite this exploitation of labor power, how their can be profit et al. at all. But, production and circulation are a unity, hence the third volume addresses the totality of the process….which I think is when the necessity of crisis to re-set the value of capital, within the ever narrowing limits imposed by the development of the productive forces to a point increasingly incompatible with the anarchy of capitals is demonstrated. So I do not agree that Marx was wrong in seeing no contradiction between volume one and two, much less volume three. Engels was a brilliant man and it doesn’t seem likely to me he managed to edit the manuscripts into nonsense. either.

It was of course Keynes who was compared to Hegel. Again, my proofreader is so skilled as to see what I meant rather than what I wrote.

What do you think about Asiatic Mode of Production?

the economy of the really existing world cannot deal with real life because if so it would stand as an indictment against capitalism. The American National Bureau of Economic Research has collected 33 of them since 1854 alone, an average of 2 per decade, there having never been a period without a crisis for more than 11 years. Someone who was not an economist – as Marx would say – should deduce that capitalism contains some intrinsic characteristic that leads to it, which is why economists cannot study real life because they would reach the conclusion that capitalism is useless and must be replaced. , and that cannot be allowed.

Your Host Nicholas Stern: “Economics has contributed disturbingly little to discussions about climate change. As one example, the most prestigious mainstream Quarterly Journal of Economics, currently the most-cited journal in the field of economics, has never published an article on climate change!” –> As It Should.

Just like health, climate cannot be entrusted to economists, those sophists, never! The corresponding ailments, disease in the former and climate change in the latter are competencies of *doctors and climate scientists respectively, the less we put up with pedantry of the intruders/marauders.

The best position to allocate like we’d to any human or layman on this planet is stakeholding and on this, everyone has to take responsibility in diverse dimensions.

Sorry Nicholas Stern.

Karl Marx, I think remains the most illuminating economist (social scientist & philosopher) that has ever been in all of human history. To show so succinctly that human labour power (performed by those who do not own the means of production) is the one and only source of all profit, and that all capital in existence today derives form expropriated profit, was a revelation akin to Issac Newton’s law on gravitational theory. It baffles me as to why so many mainstream economists actively choose to ignore or at best gloss over something that is so fundamental.