Inflation, risk of global recession, growing inequality and rising debt for the global south, global warming, war – I could go on. These are the fault-lines exhibited in the world economy in 2022. What is to be done about it? It is revealing to consider the solutions offered by analysts writing for the IMF in its monthly Finance and Development (F&D) journal.

The new chief economist for the IMF, Pierre-Oliver Gourinchas kicks off in the June issue of F&D. “Like an earthquake, the war has an epicenter, located in Russia and Ukraine. The economic toll on these two countries is extremely large.” Gourinchas lists the toll. The first impact is on the price of commodities. Second, trade flows have been heavily disrupted, Third, the war caused financial conditions to tighten.

He continues: “the earthquake analogy is perhaps most apt because the war reveals a sudden shift in underlying “geopolitical tectonic plates.” The danger is that these plates will drift further apart, fragmenting the global economy into distinct economic blocs with different ideologies, political systems, technology standards, cross border payment and trade systems, and reserve currencies. “The war has made manifest deeper divergent processes. We need to focus on and understand these if we want to prevent the ultimate unraveling of our global economic order.”

He recognizes that US imperialism will remain the hegemonic power but while: “the dominance of the US dollar is absolute and organic (it is ) ultimately fragile. This is one of the fault lines in the current economic order. How this transition is implemented could have a major effect on the global economy and the future of multilateralism.”

What’s the answer? Apparently, it is the IMF! According to Gourinchas, “this is a world that needs the IMF more, not less. As an institution, we must find ways to deliver on our mission to provide financial assistance and expertise when needed and to maintain and represent all our members, even if the political environment makes it more challenging. If geopolitical tectonic plates start drifting apart, we’ll need more bridges, not fewer.”

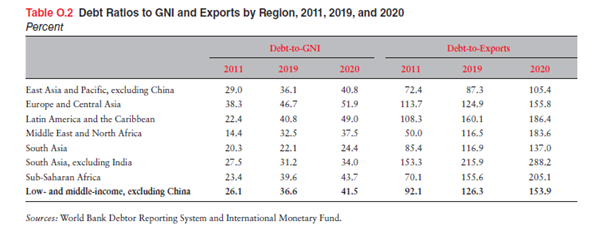

This is an ironic conclusion given the record of the IMF in squeezing down growth and public spending and living standards in so any countries over the last 40 years in the interests of ‘reducing debt and fiscal probity’. The IMF failed to alleviate the rise in poverty for millions from the COVID slump and still offers no effective program to relieve billions of people living in countries with huge debts. Not a word from Gourinchas about cancelling those debts. The IMF is less a bridge over the global fault-lines and more a contributor to more fissures.

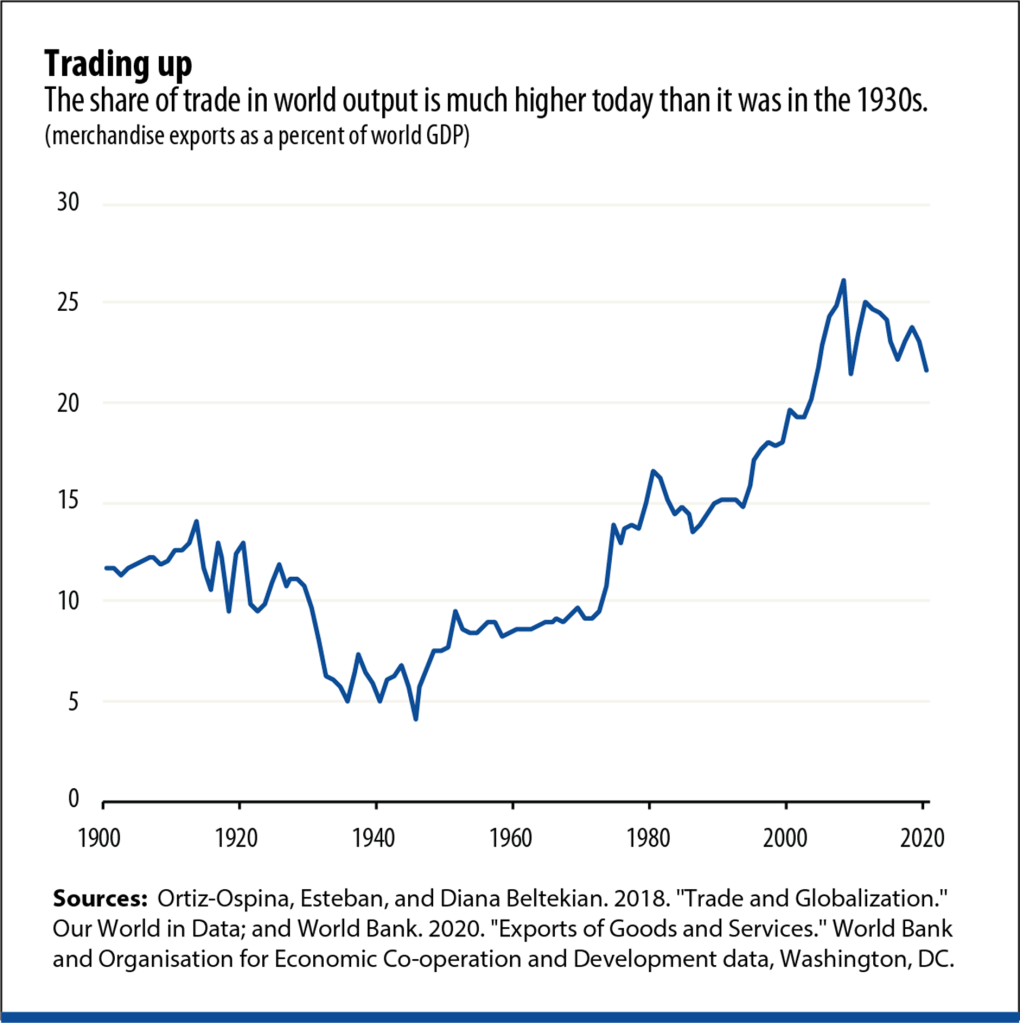

In another piece, Nicholas Mulder, the author of The Economic Weapon: The Rise of Sanctions as a Tool of Modern War, explains how the sanctions being imposed by ‘the West’ on Russia and also those already on China have serious consequences globally particularly for poor countries: “sanctions have global economic effects far greater than anything seen before. Their magnitude should prompt reconsideration of sanctions as a powerful policy instrument with major global economic implications.” Sweeping sanctions against Russia have combined with the worldwide supply chain crisis and the wartime disruption of Ukrainian trade to deliver a uniquely powerful economic shock. Additional sanctions on Russian oil and gas exports would magnify these effects further.

Again, what’s the answer?. Well, of course, ending the Russia-Ukraine conflict is the first that springs to mind. But that alone will not stop the spread of sanctions (trade, technology and finance) as weapons of war are now being used by the imperialist bloc against any nations who resist the interests of that bloc.

Mulder says that it is in the interest of the well-being of the world population and the stability of the world economy to take concerted action to counteract the spillovers of sanctions on Russia. A number of policy adjustments could help. First, advanced economies should focus on long-term infrastructure investment to ease supply chain pressures, while emerging market and developing economies should make income support a priority. Is any of that happening?

Second, advanced economy central banks should avoid rapidly tightening monetary policy to prevent capital flight from emerging markets. This solution flies in the face of the interest rate hikes being pursued with vigour by nearly all the major central banks in order to ‘control inflation’.

Third, looming debt and balance of payments problems in developing economies can be tackled through debt restructuring and increases in their allotments of the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights, a type of international reserve currency. Debt restructuring, let alone cancellation, is being ignored by the IMF, which still demands its pound of flesh.

Fourth, humanitarian relief should be extended to distressed economies, especially in the form of food and medicine. Tell that to poor countries lacking vaccines during COVID and now facing food faines.

Fifth, the world’s major economic blocs should do more to organize their demand for food and energy to reduce price pressures caused by hoarding and competitive overbidding. How is that to be achieved when food distribution globally is controlled by a handful of monopoly trading companies?

Mulder’s solutions are in the interests of the well-being of the global population, but not in the interests of big capital, finance, fossil fuels and corporate profits. He concludes: “Unless such policies are put in place in the next few months, grave concerns about the world economic outlook for 2022 and beyond will be justified.” But there is fat chance of any of these measures being agreed globally, let alone ‘put in place’.

Then there is global warming and climate change: Tharman Shanmugaratnam is senior minister in Singapore and chair of the Group of Thirty (the new international banking forum). In his article in F&D, he is concerned that cutting off Russian gas supply to Europe and elsewhere may be very costly to millions, but he reckons that it also offers an opportunity to move towards the reduction of fossil fuel emissions to reach net zero by 2050. But even that seems unlikely given the sharp increase in coal production to compensate for gas supply reductions and the expansion of degrading shale oil production in the US.

To convert the world economy from its current path to one that achieves net-zero carbon emissions by mid-century would cost $25trn in infrastructure investment. Shanmugaratnam says: “Measured from a societal perspective (my emphasis), these investments pay for themselves many times over, given that fossil energy use costs more in external damages than it adds value to GDP.” So Shanmugaratnam wants to invest in what he calls ‘public goods’: “we have to invest at significantly higher levels, over a sustained period, in the public goods needed to address the world’s most pressing problems. We must make up for many years of underinvestment in a wide range of critical areas—from clean water and trained teachers in developing economies to upgrades of an aging logistics infrastructure in some of the most advanced economies. But we also have the opportunity now to spur a new wave of innovations to tackle the challenges of the global commons, from low-carbon construction materials, to advanced batteries and hydrogen electrolyzers, to combination vaccines aimed at protecting simultaneously against a range of pathogens.”

Yes, sounds great. But two things spring to mind here. Why has there been so much ‘underinvestment’ in such ‘critical areas’ up to now? Shanmugaratnam offers no explanation, but the evidence (expounded many times on this blog) shows that it is the failure of the capitalist sectors of the world economy to invest because profitability in ‘productive investment’ has been in long-term decline, particularly in the 21st century. Capital has instead gone into financial and property speculation, driven by low or near zero interest borrowing rates.

Time for a change says Shanmugaratnam: “We must now reorient public finance, in partnership with philanthropic capital where possible (! – MR), toward mobilizing private investment to meet the needs of the global commons (my emphasis). So the answer is to rely on private capital backed by public money to get the capitalist sector to invest. That approach has been tried over and over again and clearly failed. Yet Shanmugaratnam persists with this solution (as he must): “almost half the technologies needed to reach net zero by mid-century are still being prototyped. Governments must put skin in the game to leverage private sector R&D (my emphasis again), and promote demonstration projects, to accelerate the development of these technologies and bring them to market. Besides getting to net zero on time, they should aim to spur major new industries and job opportunities.”

He recognises correctly that: “the social returns to protecting the global commons will typically be far in excess of the private returns” and “Developing and producing vaccines at scale for the next pandemic is a strong illustration of the point. A project to immunize the world’s population even six months earlier will save trillions of dollars and countless lives.” In which case, why not turn to the public investment? Well, no, instead this “makes a strong case for the public sector to share risks with private investors.” God help the public sector then.

Shanmugaratnam calls for global coordination: “the additional international investment required to plug major global gaps in preparedness, with contributions fairly distributed across countries, will not only be affordable for all but also enable us to avoid costs that would be several hundred times larger if we fail to act together to prevent another pandemic. The longstanding aversion to collective investment in pandemic preparedness reflects political myopia and financial imprudence, which we must overcome urgently.”

Indeed! But what is Shanmugaratnam’s answer? The usual one: the World Bank “must pivot more boldly toward mobilizing private capital, using risk guarantees and other credit-enhancement tools rather than direct lending on its own balance sheet.” Exactly what the World Bank has been up to for decades, using public money to fund private capital schemes.

As for global coordination to achieve these social tasks, Shanmugaratnam says that “a more effective multilateral system will require fresh strategic understanding between major nations, most important, between the United States and China, as the world shifts irreversibly toward multipolarity.” Given the latest NATO summit, which aims to surround and ‘contain’ China as an enemy of the West, global coordination is clearly off the agenda.

Shanmugaratnam is clear: “We can be under no illusion that an integrated global order, with its deep economic interconnections between nations, will on its own assure us of peace. But economic interdependence between the major powers, save for sectors impinging on national security (! MR), will make conflict far less likely than in a world of increasingly decoupled markets, technologies, payment systems, or data.” But how can there be ‘economic interdependence’ in a world dominated by an imperialist bloc, led by the US, aiming to work against those major economies that resist its interests (China, Russia and even India)?

Private capital has failed to reduce poverty and inequality – on the contrary. It has failed to invest in the infrastructure and technology to raise living standards globally and reduce carbon emissions – on the contrary, fossil fuel production and profits continue to rise. It’s clear, even if the IMF experts do not admit it, that public investment for common good should replace capitalist investment for profit to meet the needs of the many and to introduce the technology to reduce emissions and expand vaccines And fossil fuel companies need to be brought under public ownership and control and phased out. Global coordination is impossible while imperialist powers dictate the terms. Peace and imperialism is an oxymoron.

All I can say to this is; Ay-men bruthah!

“And fossil fuel companies need to be brought under public ownership and control and phased out. “-

Exactly…yet you still refuse to authorize the public sector to create – ex nihilo – its own debt-free money, thereby playing into the hands of the Instant Misery Fund….

Neil,

It is said by some that the universe was created ex nihilo. Looking around this seems to have worked reasonably well on any scale.

However, to expect governments to have the same creative power to materialize resources which can be deployed to desirable ends is not so secure.

Creating money ex nihilo is one thing, creating useable real resources, either privately or publicly, is another.

Henry,

assuming enough resources exist to build solar/wind + grid + storage for a green economy, the only cost is an opportunity cost – in resources – not money which is created ex nihilo.

Hence the public sector – which unlike the private sector, can create *debt-free money* ex nihilo – should manage the transition because the electorate will reject the high carbon price demanded by the profit-seeking private sector while it closes down its profitable fossil sector.

4th Para:

He recognizes that US imperialism will the hegemonic power but while:

thanks corrected

The IMF cannot forgive its debts for two reasons:

1) every decent historian knows the IMF is actually a branch of the US Department of the Treasury. It is the US Treasury Secretary – not the IMF Managing Director – who is the true IMF President;

2) even if we ignore fact #1 (say, a huge reform of the IMF takes it off American hands), it wouldn’t change the fact that the IMF, albeit not a State, is a Leviathan. A Leviathan will always act to preserve itself, which means to preserve all of its powers. If the IMF forgave the debt it owes, it would lose its leviathanic properties, therefore lose its reason-to-be (ditto for the World Bank).

On the main subject, it is interesting that, from the point of view of the Western Civilization (i.e. the First World), the rise of multipolarity remembers a lot of the Bronze Age Collapse – an age which its dominant and middle classes remembered fondly as a cosmopolitan paradise, only to be brutally defiled by the brute Sea Peoples. Maybe not by chance the term “neofeudalism” was coined precisely in 2008 by an American capitalist.

Maybe it’s time for Putin and Xi to discard their slick bankers’ suits for Castro fatigues or Mao jackets…?

Xi certainly wears Mao jackets for PR purposes, more recently during the centenary of the creation of the CPC.

No, it’s time for the members of the UNGA to demand that the members of the UNSC relinquish their power of veto.

In 1946, the great powers refused to sign the UN charter unless they were granted power of veto — making a mockery of “international law” which is why most wars since 1946 have been proxies between the US and USSR (now Russia).

Then we can reform the US stooge IMF – Instant Misery Fund; and reform the WTO to oversee fair trade not “free” trade.

The dichotomy between public and private is a false one because that wouldn’t change the mode of production, which would still be capitalist.

It’s the revival of the old social-democratic mantra, whose doctrine stated that, by reforming the capitalist state piece by piece, through consecutive election victories by the social-democratic party, capitalism would sleepwalk to socialism. This thesis not only is false, but has the polar opposite effect of what was intended: it makes capitalism stronger, not weaker. This is because the social-democrats’ reforms subvert the State but strengthen the nature of the Leviathan, which not only remains capitalist, but gains extra powers, in the form of the Welfare State. The Leviathan thus not only continues to exist, but becomes the custodian of socialism also, that is, it becomes the limit of imagination of the social-democratic movement. In fact, we can ultimately describe social-democracy as the self-preservation instinct of the unions as a Leviathan; or, alternatively, the unions become integral part of the State, therefore an institution, that is, a state formation with leviathanic powers.

In the socialist mode of production, the Leviathan must necessarily be much weaker than in the capitalist mode of production – not only that, but it must get progressively weaker as its development of the productive forces advance historically. That’s an absolute limit to socialism, beyond which no possible variation of it can exist. Social-democracy (the Welfare State), therefore, is not a form of socialism and is not even a transition of the transition, i.e. a transition to socialism. In fact, the social-democracy transitioned to something, it transitioned to some form of fascism (nazism in Germany; exceptionalism in the USA; many forms of racial-cultural supremacism in Europe post-2011), political-ideological formations which the Bolsheviks originally called “social-fascism”.

China’s Market Socialism with Chinese Characteristics is a form of socialism (if only a “transition of the transition”) because, in China, the Leviathan is weaker even though the State appears to be stronger. Of course, that doesn’t mean victory: the capitalist world is still strong enough to destroy China. But that would be an exogenous factor, the same factor that dissolved the USSR (which was successfully besieged and destroyed, after 73 years).

Just to clarify, with “leviathan” here you mean essentially bureaucracy, or undemocratic centralized power?

Otherwise, excellent analysis re:social democracy, its prospects (fascism), and its relationship to sovialism; also re:USSR’s controlled demolition at the hands of American imperialists

“State” is simply the specific, juridical-military form of the Leviathan – what we colloquially call “the government” in the USA. It’s the Leviathan in a historically specific state (e.g. monarchy/kingdom, parliament, republic, military dictatorship, etc. etc.).

Leviathan is the State in the philosophical sense.

This differentiation looks silly at first glance, but it is crucial to understand Marx. For example, many Marxists condemn the Bolsheviks for their dekulakization policy, which started at the end of the 1920s, for being anti-proletarian (therefore, antimarxist) because those kulaks were not actually kulaks but just a little bit better off peasants. They use as evidence the endless hair-splitting debates of the Supreme Soviet on what constitutes a kulak or not (e.g. if he has one horse, he is a kulak, etc. etc.), which they interpret as ideological degeneration and a symptom of bureaucratization (i.e. the Leviathan becoming stronger).

However, that’s not the case: the Bolsheviks were correctly applying Marxist theory when discussing the details of what constituted a kulak. Marx delineated a theory of History, not a theory of public administration: his model is only absolutely true when you take History as a whole, not in parts. The USSR was not the whole History, but just a historically specific Westphalian nation-state, in a historically specific stage of the capitalist development of the productive forces, occupying a very limited and historically specific piece of planet Earth (even though a huge piece, by the standards of the epoch). The Bolsheviks quickly realized they weren’t the end of History after the second attempt of a communist revolution in Germany failed spectacularly in 1923, and, after the spirit of Locarno (1926), they knew WWII was coming (the only difference was that, initially, they imagined the aggressor would be the UK, not the yet-to-be-born Nazi Germany), they knew they had little time to industrialize and modernize their army.

Imagine if the Bolsheviks kept feeding themselves the illusion of a world revolution after 1926 (we know, from declassified documents from the imperialist powers, that no attempt of the Comintern to generate communist revolutions in their respective countries ever had any chance of being successful and were not taken very seriously). They would squander their squalid resources for a decade before being crushed, partitioned and colonized by the Germans (as what survived of the Generalplanost suggests). Sometimes, you have to admit you’re weak in order to get strong.

Another interesting fact that can only be perceived by differentiating the State from the Leviathan is Nazi Germany itself: Hitler didn’t change one line of the Constitution of the Weimar Republic. Nazi Germany was, juridically speaking, literally the Weimar Republic. This can only be explained scientifically if we can extract the substance of the State (the Leviathan) from the State as an institution (the Government).

So, Leviathon is an ideological construct, aka Hobbes that stands ‘outside’ government or the state? It’s what powers capitalism (and the capitlist), is that what you’re saying?

@ barovsky

In order to not confuse the State specifically and the State as a long-term History entity (substance), I use the term “State” to designate the former and the term “Leviathan” (in homage to Thomas Hobbes’ magna opus, titled “Leviathan or The Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil”) to designate the latter. It’s just a matter of clarification.

But one could call both “State” without being incorrect.

Thomas Hobbes wasn’t the first to develop a theory of the State (not even close). Theories of the State exist since at least the Ancient Greek philosophers (Plato, Aristotle).

The general definition of the State (Leviathan), as synthesized by István Mészáros, is the “command structure [superimposed] on societal decision-making.”

Earth-shaking news! Regardless of the government, the states serves the interests of property, the mode of production, and the needs of the ruling class. Strip my gears and call me shiftless……

Excellent. But you make nothing of the inherent contradictions within the capitalist mode of production that have led up to the present (really century-long) insoluable crisis, the solution of which has been global capitalism’s production of endless wars of capital, human, and ecological destruction….Which, I think, is Robert’s point.

correction: “Which, I think, is Robert’s conclusion” is not correct. It’s really the conclusion I derive from Robert’s piece.

They all continue to valid and in operation. The analysis of the State doesn’t preclude the analysis of the Economy.

vk,

“The dichotomy between public and private is a false one because that wouldn’t change the mode of production, which would still be capitalist”.

That statement ignores productivity which is enabled by the public sector. eg education; and even if steel is produced by the capitalist private sector, the steel can be utilized by the public sector to build public infrastructure.

That debate pertains to the mode of production, not to the analysis of the State.

The wage system seems to operate like a transmission belt from labour to capital. Who’d a thunk?

In any case, if the bourgeois quoted in this piece are the best the ruling class can come up for advice on how to run the economy as the greenhouse gas chamber fills, I vote no confidence and await the motion of the working class to emancipate itself from the bondage of Capital. Of course, labour can’t do that unless it knows that the “wage system seems to operate like a transmission belt from labour to capital” and inscribes on its banners, “Abolition of the wage system”.

(Quick google}

“What Marx most likely would have asserted is that the existence of bureaucracy in government is a second-order factor, and that the main event is the existence and use of political power through the tools of state action”.

In MMT, the consolidated government sector – treasury and reserve bank – is a first order factor, allowing, for example, nationalization of the fossil industry at no cost the the public sector.(apart from ‘opportunity’ resource cost to the nation.

“In MMT, the consolidated government sector – treasury and reserve bank – is a first order factor, allowing, for example, nationalization of the fossil industry at no cost the the public sector.(apart from ‘opportunity’ resource cost to the nation.”

In other words, the state is to seize the fossil fuel industry and “reimburse” the owners by “printing money” (crediting the owners in newly created fiat money.) This scheme can’t work because it is based on an incorrect theory of money: money is not whatever the government declares it to be but what is accepted as money in the market. The state can influence this “choice” but only so long as it remains powerful enough to, say, collect taxes, for instance. The US state’s power comes in large part from the cooperation/collusion of the dominant US based transnational corporate capitalist class, particularly the monopoly intellectual property rentier class who in turn depend on the US state and its satellites for the enforcement of patent/copyright laws. If the state starts to print money like crazy, not to enrich capitalists as they have been doing but for the benefit of the people the capitalists will “lose confidence” in the state’s money and the state itself: the result would inevitably come to a civil war.

Gabe, governments have nationalized industries in the past (though I take your point: when Mosaddegh tried to nationalize Iran’s oil industry in 1953, the CIA instigated a coup against him – evil capitalists indeed).

Note: fiat money is accepted by the citizens because they need it to pay taxes levied by the government.

But your claim that (the value of) money is determined solely in the market is not the whole story; rather the value of a nation’s currency is determined by a nation’s productivity, to which both the public and private sectors contribute.

(For example, a nation could be entirely non-market or “planned” (at least in theory); and money would still certainly have value