Twilight capitalism: Karl Marx and the decay of the profit system is the best book on Marxist political economy in 2021. Authored by Murray EG Smith, Jonah Butovsky and Josh Watterton, these Canadian-based Marxist economists have delivered a comprehensive and often original analysis of global capitalism in the 21st century.

As the title of the book suggests, the authors argue that capitalism is now in its twilight phase before its demise as a functioning social system. To prove this thesis, the authors deal with all the Marxist theories of crises in capitalism, answer the critiques of the Marxist analysis by mainstream and heterodox economists and provide original empirical evidence to support the Marxist paradigm. As such, this is an ambitious book, but its ambition is successfully achieved.

As the authors start by saying, “this book is a hybrid of sorts”, namely an updated version of previous work by Murray Smith, namely Global Capitalism in Crisis: Karl Marx and the Decay of the Profit System published in 2010 and also Smith’s excellent 2018 book, Invisible Leviathan, which takes the reader deftly through the debates over the validity of Marx’s law of value.

The book begins with the ‘here and now’ – and so with COVID pandemic. Over two chapters, the authors spell out the origins and course of the pandemic, making, in my view, a key point. The COVID slump may have been triggered by a global health crisis, but even before the pandemic struck, global capitalism had been in a period of depression exhibited by low economic growth and poor productive investment and, above all, by low and falling profitability of capital – the key ingredient of ‘twilight capitalism’.

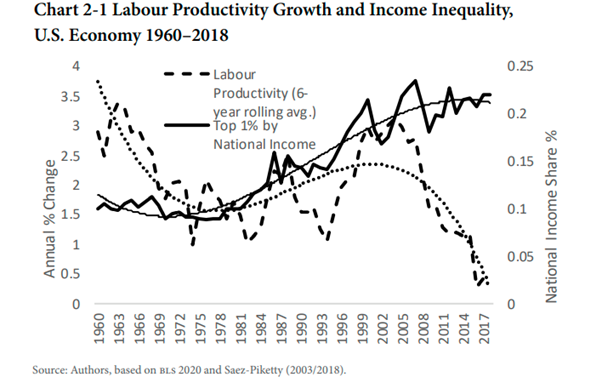

In the previous four decades before the pandemic, inequality of incomes rose as most of the gains in productivity did not ‘trickle down’ to labour.

The average annual rate of growth of labour productivity fell over the long term (largely due to a slowdown in new fixed capital formation), but the share of income earned by the top 1 percent increased dramatically, rising almost without interruption from about 12 percent in 1985 to about 22 percent in 2017. On the other hand, wages, particularly for the bottom 80 percent to 90 percent of income earners, either stagnated or declined in real terms between 1970 and 2015.

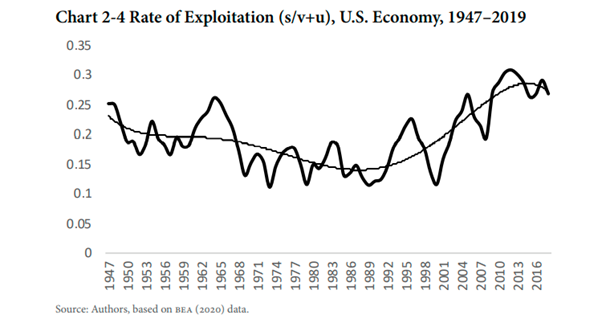

Smith et al offer a Marxist insight into this rising inequality of income and wealth since the early 1980s – namely a rising rate of exploitation of labour by capital, as measured by the surplus appropriated by capital in profits, interest and rent (s) compared to the wages of productive and unproductive (but necessary) workers (v+u).

In the next three chapters the authors get down to the nitty-gritty of Marx’s account of capitalist crises, both theoretically and empirically. The key underlying cause of periodic capitalist crises is the recurring problem of insufficient production of surplus value, a problem that has continually mutated and worsened since a new material basis for capital accumulation was established in the aftermath of World War II. The financial crisis of 2007–09 was the outcome of a decades-long effort on the part of the capitalist class, in the United States and elsewhere, to arrest and reverse the long-term decline in the average rate of profit that occurred between the 1950s and the 1970s.

The Great Recession was the cumulative and complex result of a series of responses by the capitalist class to an economic malaise that can be traced to the persistent profitability problems of productive capital — the form of capital associated with the “real economy.” The authors present the evidence of numerous empirical studies by Marxist economists, and their own work on the US and Canada, some of which has been published in World in Crisis (2018), as edited by Guglielmo Carchedi and myself.

The authors explain that the characteristic form of capitalist economic crisis is overproduction. Overproduction means that not enough commodities can be sold (or markets cleared) at prices that permit an adequate profit margin; and since profit drives capitalist production, economic growth must slow or even decline, throwing large numbers out of work, bankrupting many firms and rendering much productive plant idle.

But overproduction is only a description of a capitalist crisis, not the cause. As the authors say, “according to Marx, a variety of unique circumstances can trigger crises of overproduction; however, the most important recurrent cause is the tendency of the rate of profit to fall due to an overaccumulation of capital and inadequate production of surplus value. If overproduction involves the social capital’s inability to realize the full value of the total commodity output, this “crisis of realization” is ultimately the surface manifestation of a crisis of valorization — a crisis in the production of sufficient quantities of new value and surplus value.”

They involve Marx’s double-edge law of profit, namely that “a fall in the average rate of profit need not always precipitate a conjunctural crisis of capital accumulation, such a crisis is not always preceded by a particularly sharp fall in the average rate of profit. A fall in the mass of profits combined with other disturbances may suffice.” The fall in the mass is a product of a fall in the rate of profit.

The causes of the fall in the profitability of capital in the major economies over the long term are much debated by Marxist economists. The authors defend the view that the main determinant is a secular rising organic composition of capital (increased investment in means of production over wages of employment). As the organic composition of capital rises, the average rate of profit on capital will fall.

In promoting Marx’s law of profitability, the authors deliver a significant critique of other explanations, in particular that of Robert Brenner in his signature work of the late 1990s (Uneven Development and the Long Downturn: The Advanced Capitalist Economies from Boom to Stagnation (New Left Review 229, May–June 1998), which dominated thinking at the time. Smith et al: “Brenner’s approach is sharply at odds with our Marxian theorization of a valorization crisis and is criticized on that account. In particular, inasmuch as Brenner’s thesis rests upon a concept of “realization crisis” that has much more in common with the Keynesian tradition than with Marx’s theory, our critique of Brenner serves the larger purpose of revealing the basic incompatibility of even the most “left” versions of Keynesianism with Marxism.”

I would add that, for me, Brenner, in rejecting Marx’s law of a rising organic composition of capital as the underlying force for falling profitability, falls back on the position of Adam Smith, namely profitability falls because of increased competition between capitals. The Smithean cause opens up the response that, if only wages did not rise too much, profits can stay up and so capitalism can avoid crises.

The ‘profit squeeze’ theory of crises is the reciprocal of Brenner’s thesis. A theory of crises based on wages squeezing profits was popular among Marxists in the 1970s, but has lost its traction now as the rate of exploitation of labour by capital has risen sharply in the 40 years; and yet average profitability is near all-time lows. Only post-Keynesians, following Keynesian-Marxist Michal Kalecki, now talk about ‘wage-led’ (wages too low) or ‘profit-led’ (profits too low) explanations of crises. This neo-Ricardian explanation of crises no longer has support among most Marxist economists, given the evidence of profitability decline, particularly in the 21st century.

There is an important chapter on alternative theories of crises, where the authors critique theories from various ‘radical heterodox’ economists. Popular radical economists like Mariana Mazzucato and Stephanie Kelton are taken to task here. These economists ignore or reject Marx’s value theory and instead focus on Keynesian ‘lack of demand’ analyses, ‘market failure’ or financial ‘instability.’ But they do not offer a coherent explanation of crises or sufficient empirical evidence to support these alternatives.

The current popular alternative to Marx’s law of profitability as the underlying cause of capitalist crises is ‘financialisation’. And Smith et al agree that there has been a massive expansion of the financial and property sectors (FIRE) and FIRE profits in the last 40 years. But they show much of this is fictitious, ie it is paper profits that eventually won’t be ‘realised’ from value created in production. What happens in the value-creating sector will be decisive.

The authors comment: “in our view, the financialization phenomenon is yet another perverse expression of the profitability and valorization problems of productive capital. Financialization has not “transformed” capitalism in some fundamental way, allowing it to dispense with the exploitation of productive wage labour as a means to generating profit. On the contrary, the phenomenon testifies to the decay of the profit system and the frenzied efforts of powerful circles within the capitalist class to accumulate immense fortunes without contributing (even in indirect ways) to the production of commodities and surplus value.”

Financialisation is the consequence of the malaise of the productive sector. Capitalists now desperately search for profit from buying and selling money and credit rather than from exploitation of labour in production. The authors remind the reader of Marx’s observation in Capital Volume Two that, to the possessor of money capital, “the production process appears simply as an unavoidable middle term, a necessary evil for the purpose of money-making.” As Engels commented: “this explains why all nations characterized by the capitalist mode of production are periodically seized by fits of giddiness in which they try to accomplish the money-making without the mediation of the production process.”

It is not just in economics that a failure to use Marx’s value theory leads to a misunderstanding of the cause of crises; it also has political consequences on policy and the authors spend some ink considering the crisis in the radical left, particularly in North America. They make the point that Marx’s law of profitability is not only the basis for understanding recurring and regular crises in modern capitalist economies, but it also “provides an extremely powerful but also essentially simple argument in support of the proposition that the development of the forces of production under capitalism points with inexorable logic toward socialism.” The secular decline in profitability implies the transient nature of the capitalist mode of production as crises intensify. Indeed, the expansion of robots to replace labour in production will accelerate that.

This brings the reader to the final chapter on socialism. Albert, Gindin, Mandel and others are cited in an unfortunately rather short discussion of the key issues of democratic planning, in which the authors offer “a critical historical retrospective on what was sometimes called “actually existing socialism” in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, a consideration of some recent “blueprints” for building a socialist society and an argument in support of “proletarian-democratic central planning as a necessary element in the transition to a global socialist civilization truly worthy of the name.”

In the big debate on the nature of China, Smith, Butovsky and Watterton do not dodge the issue. I quote at length: “China is not now and never has been fully socialist. Rather, it is best understood as a transitional socio-economic formation, one that has combined elements of capitalism and socialism since the victory of the Chinese revolution in 1949. To be sure, the balance of these elements has shifted massively over time, and there is unquestionably a very real possibility that the capitalist elements may yet prevail over the socialist ones. But a convincing case has not yet been made that a “capitalist counter-revolution” has already occurred. The thesis that China has been completely reabsorbed into world capitalism, that the Chinese party-state bureaucracy is now an instrument of capitalist class rule and that the Chinese economy is subordinate to the law of value is simply not credible. What’s more, to credit China’s rapid economic development and modernization to the restoration of capitalism is to give considerable ground to those who reject the Marxist thesis that, by the twentieth century, capitalist social relations had become a brake on the development of the productive forces of humankind.”

As humanity faces impending disaster from global warming and climate change, Smith, Butovsky and Watterton pose what they call “a difficult paradox” for socialists. “In order to win a world in which we can truly realize our most authentic human capacities, we need to act in ways that are hard-headed, strategic and disciplined. Capitalism cannot be reformed, tweaked or reoriented. Rather, it must be replaced … and that, quite simply, will be no easy task. The existing capitalist ruling classes will do everything in their power to prevent the destruction of the system to which they are wed. We must be no less determined in our efforts to prevent them from having their way.”

Thank you for the notice of this book Michael, it looks interesting. Please also see a recent pamphlet on manufacturing in Britain.

Click to access Rebuild-British-Manufacturing.pdf

On Mon, 8 Nov 2021 at 16:56, Michael Roberts Blog wrote:

> michael roberts posted: ” Twilight capitalism: Karl Marx and the decay of > the profit system is the best book on Marxist political economy in 2021. > Authored by Murray EG Smith, Jonah Butovsky and Josh Watterton, these > Canadian-based Marxist economists have delivered a comprehensi” >

Doug, Next time just leave a link.

HI Michael,

Do we have equivalent graphs to those used in Twighlight campaitalism for Britain?

Cheers

Doug.

On Mon, 8 Nov 2021 at 16:56, Michael Roberts Blog wrote:

> michael roberts posted: ” Twilight capitalism: Karl Marx and the decay of > the profit system is the best book on Marxist political economy in 2021. > Authored by Murray EG Smith, Jonah Butovsky and Josh Watterton, these > Canadian-based Marxist economists have delivered a comprehensi” >

https://www.academia.edu/20037096/UK_rate_of_profit_and_British_economic_history

Thank you for this comprehensive review of a splendid defense of, and up-to-the-minute assertion of the Marxist Method. Globally the evidence is mounting to disprove the confused and confusing torrent of hostile misrepresentation by the Keynesian brigade and their bourgeois bedfellows. Keep up your great work, Michael. I will republish the review in Ireland.

As in your position and analysis, these authors believe that financial instability and crises (fictitious capital based) is just a ‘reflexion’ of crisis in productive capital, where exploitation of productive labor leads to rising organic composition of capital and in turn falling rate of profit–from production of goods with productive labor only. What you and they don’t admit is that the profits data you use–provided by capitalist government accounts–includes portfolio financial asset profits! Studies show about one-third of the profits reported by large corps today are financial (portfolio) profits. So you’re using data for fictitious capital to show a falling rate of profit. That’s un-Marx, by the way. Secondly, the data on profits you use are corporate profits, thus ignoring non-corporate profits (business income).Capitalist government accounts conveniently separate business income profits (and then underestimate the same) in order to lower the level of corporate profits. Thirdly, there’s no way you can accurately estimate corporate profits on a global scale, given the various ways capitalist governments help hide them in their national accounts. For these reasons you cannot accurate provide true data with which to argue either the organic composition or the falling rate of profit. Marxist economists must develop a more convincing analysis integrating portfolio financialized profits (fictitious) into the labor theory of value. Fictitious capital is more destabalizing of capitalist cycles than you want to admit. Abandon the ‘reflexion’ hypothesis. Explore more the possibilities of explaining crises by developing further Marx’s disproportionality thesis (adapted to how real capital and financial capital interact to shift profits from real production to financial asset profits). The key is to expand on Marx’s idea of ‘secondary exploitation’, a more important point made in Vol 11 than the falling rate of profit (from productive labor only) point.

Jack you can calculate global profits, because though profits are put through the rollers in tax havens to strip away taxes, they do end up back in the country where the corporation is headquartered. It is why I only use pre-tax profits in my calculations and never after-tax profits because of all this tax dodging.

Jack has apparently already read the book (that was fast!) and raises potentially valid points, if accurate. Having not yet read it, all I can say is that in principle: 1) Not all finance capital is ipso facto fictitious capital, and therefore any adjustment must tease this distinction out; 2) in terms of a disproportionality thesis, *Unproductive capital* extends well beyond finance, and enters in particular into the sphere of social reproduction, whose processes are today dominated by the capitalist mode of production. Ben Fine called these “systems of provision” and involve all the well known crisis sore points of contemporary capitalism: Health care, education, housing, transportation, military and security and so forth. Capital investment into these “provisioning systems” is by definition non-productive, even as they provide expanding markets for actual productive capital to sell into. That is because these are systems of “associated consumption” for the purpose of social reproduction, not to be confused with the expanded reproduction of productive capital.

Under capitalist social domination, these non-productive sectors appear as presumably productive “branches of industry” with their own profit shares, but also must be factored out of the gauge of the actual rate of profit of productive capital.

Brad and others of course, I’d appreciate your thoughts on the nature of women’s reproductive capacity and its role from an economic perspective? Would this factor not be a “productive” capital that seems often not figured into either social or fixed capital, seemingly rendered invisible? But if indeed fictitious capital and its influence creates inherent contradictions in lowering the rate of profit because of capitalist greed to reap profits rather than actual economy and thereby seeking to remove workers from the picture in the long term for the purpose of the more short term, myopic, view to increase profitability, wouldn’t this primary engine for generating both production and labor (i.e., surplus value/profit) be a threat and a contradition to the designs inherent in seeking to remove labor as a way to enhance profitability? Yes, I may be confusing a few things, not being a true economist, but I do wonder if Marxist economic theory directly includes this kind of point even as Engels in particular but Marx as well, had much to say about women’s role in the development of the capitalist mode of production.

I’ll appreciate any and all guidance here.

best regards and solidarity,

Manuel Barrera, PhD

“Fictitious capital is more destabalizing of capitalist cycles than you want to admit. Abandon the ‘reflexion’ hypothesis”

Nobody says it doesn’t. But the point is: fictitious capital does not rise “above” society on its own. It does so when the capitalist class cannot draw adequate surplus value from the productive sector and turn to non-productive and speculative sectors. A valid critique would be that some Marxists need to make clear that the current (financial) crises of capitalism are due to its terminal and irreversible decline, not because of overproduction. Not that the latter do not occur, but their intensity is not that much threatening. Plus, the capitalist class has developed a whole field of science just to cope with the so-called “anarchy in production” problem (Operations Research).

After complaining to/that Michael (and others) “you’re using data for fictitious capital to show a falling rate of profit. That’s un-Marx..” Jack Rasmus the argues that “Marxist economists must develop a more convincing analysis integrating portfolio financialized profits (fictitious) into the labor theory of value.”

This distinction between “real” and “fictitious capital” is problematic from the getgo and IMO stems from a failure to grasp that each “single” capitalist only claims or can claim the profit that he or she individually brings to market. No such individual claims exist. The commodity is not simply a carrier of a certain quantity of surplus value, but a bearer of the internal relations of capital as expressed in all exchanges. Meaning the market doesn’t realize a profit for a capitalist, but apportions, allocates the mass of profits among all capitalists. Profits garnered in exchanges, in arbitrage, in price deviations, through interest rate variations, are not fictitious but rather are the means for accomplishing this allocation.

The harping on “fictitious profits” and fictitious capital has be going on since the 50s and 60s–with various “sources” of this “evil” identified as state expenditures, defense expenditures, real estate expenditures. I first ran into the “financial” argument about fictitious capital back in the mid 1960s when I encountered representatives of the National Caucus of Labor Committees. They made all the same arguments then that I hear now. Still doesn’t make sense to me. It might be fun to note the convergence or the similarities between Ponzi schemes and IPOs, but it’s not accurate.

What matters most of all in assessing the rate of profit, as in assessing rates of investment, or any rates, are consistency of the categories over time and the establishment of the trend. It’s perfectly OK to utilize data on corporate profits, because the corporate legal formation accounts for the vast majority of sales which form the basis for GDP calculation. It’s like using any other index. It gives us a range of movement over time.

I think there’s an inconsistency in dismissing financial profits as fictitious, and then using that fictitious category to explain the ability of capital to avoid a collapse, or to buffer the impacts of impaired accumulation etc. If it’s been going on for decades it’s no longer fictitious, just like a crisis that goes on for X number of years can no longer be considered a crisis. It’s a business plan.

The off-shoring of industrial capitalist production to the “global south and the introduction of of the illusory IT/consumer society (illusory in the sense that–like fictitious capital–it pretends to have freed the world from matter itself) is what distinguishes the very brief “golden age of capitalism” from its period of decay: neoliberalism, which is a kind of socially and environmentally degenerative disease.

“As the title of the book suggests, the authors argue that capitalism is now in its twilight phase before its demise as a functioning social system.” If that is the case they are making, then it is another deterministic approach that does not do service to Marxist thought and methodology.

That looks like the best aspect of this book. The thesis that capitalism has entered a historical period of decay dates from Lenin and Trotsky. Note that in “Imperialism…”, Lenin was quick to add that (I may paraphrase here) that “this did not mean that capital would cease expanding, on the contrary it may expand more than ever”. That thesis appeared refuted in the post war “Golden Age” – only requiring a bloody barbaric world war! – but reality in turn has refuted the Golden Agers since the 1970’s.

The only other real countertendency to decay has been China, hopefully self-explanatory. That historical processes of class societies are contradictory is hardly a concept alien to Marxism.

The thesis of capitalist decay is therefore not a “deterministic” concept.

“The thesis that capitalism has entered a historical period of decay dates from Lenin and Trotsky.” A-100-year period?

What is the age of the capitalist mode of production?

What about the dynamism if the system?

What about wars that “rejuvenate” the system?

Nowhere in the article does Roberts engage with that deterministic statement!

So what distinguishes the period of decay from the period of health? What characterizes, and distinguishes one from the other?

If I accept the existence of determinations, it doesn’t mean I’m a determinist

In 1976 Michael Harrington published a book called The Twilight of Capitalism. In he resurrects the “authentic” Marx and suggests how the application of the true doctrine demonstrates that contemporary American capitalism is in its death throes.

In was in its death throes in 1976!

The counteroffensive to increase profitability which can be dated to this period involved a massive increase in unemployment in the UK and elsewhere which greatly reduced union power and allowed companies to restore profitability by reducing labour costs. This process ran out of steam and a fresh downturn was in prospect around 1991/92. This was countered by companies focusing increasing attention on securing legal/accounting approval of novel forms of intangible capital. This process ran out of steam in 2008/09 when excessive valuation of intangible assets (CDOs etc) was exposed. Government action to prop up the system since then (continuing with Covidnomics) is at the heart of the latest stock market/property boom. A crash that must in due course come (because the increase in stock market/property values has no support in actual value creation) will be shattering. But the system’s not on autopilot: brilliant people are working out how to keep the show on the road (perhaps for just one more round of profit harvesting).

Yes!The immense and complex historical processes inherent in social systemic evolution occur over vast swathes of time – relatively speaking. A human life (typically less than a century) is an unhelpful comparator when considering the eons over which, e.g., slave society came into being, exhausted its contradictions, and was finally negated into another systemic mode. The same holds true for capitalism, as any scientific assessment will quickly inform. But there are those who prefer to dream. Facing truth can be awkward and difficult!

The same scientific analytical approach will indicate how this currently hegemonic bourgeois system is now in the Autumn of its years. Many of us have known this since the true nature and significance of the 1929 cataclysm was identified when first subjected to analysis with the evidence of its convulsions properly understood by those who chose the wit and method to perceive its historic process and reality. There are of course, those still in denial about all that. Some have chosen a counter-scientific fantasy by which they try appraise their perceptions of the movement of social history rather than the material historic movement itself, often drawing on superstition, using a denial of scientific method and so on. Almost anything rather than face evidential reality.

Isn’t it all a matter of opinion? Well, not if you seek to understand reality. The often quaint imaginings of the Anti-Marxist Brigade (including those cute ones who try pass themselves off as “marxist” while opposing its essential materialist and dialectical character) can, at times be entertaining. But they do not help us deepen our understanding of the flow of capitalist contradiction through this declining moment. And this extends the tragic results for the billions of people trapped in poverty and disease, exploitation and terror.

Yes, we must discuss alternative possibilities of the immanent motion of a dying economic mode, but not just subjectively! Grasping the objective motion of a mortally wounded economic mode may help us to consciously negate its self-destructive unconscious compulsions. And rise above the political actions of its master class. But obstructing that democratic struggle for truth by disrupting the scientific search for resolution and guiding actions is at best irresponsible. Michael Roberts has been more than patient with obstructive denials than I could be, but in that perhaps, he demonstrates both patience and strength. And I thank him for that.

Really like this post and its review of what seems an important book today. I was quite interested in the authors’ (and yours’ I imagine) analysis of China’s development and role in global capitalism and society. It seems quite satisfying, theoretically, to consider China’s intermediate nature. Things rarely are black and white. Until, you know, they are!

Thank you, for this great introduction and review. I hope I can get to to the book, but it’s helpful to know that one can stay true to Marxist principles and make original necessary advancements beyond, something I would believe Marx and Engels would likely have done if they were truly as immortal as their analysis seems to be. I bet they would be the first to hope that their analyses could finally be put to rest with the development of a newer, more original world than this one, which has more than spent its time on the Earth.

Solidarity always,

Manuel Barrera, PhD

On your recommendation I have purchased this book.

Focusing on the composition of capital may I begin with an analogy. The main determinant of our weather is the sun. At its simplest, when the sun shines it warms up and when it sets it cools down, when the sun is closest (inclination) during summer it is warmest, when it is furthest during winter it is coldest. The second most important factor is the rotation of the earth which acting on the atmosphere is responsible for the winds that form our weather, following this we have the oceans that trap heat and so on and so forth. Now there can be no doubt that the sun in this case is the composition of capital. And we can even extract a general law from its increase, namely that the more elevated the composition the greater the amount of capital that needs to be destroyed for a 1% increase in the rate of profit, therefore the more vicious the attack on workers must be and the deeper the political repercussions.

But if we are to understand developments today, while we must start with the composition of capital, we must not end with it. Sure, the stagnation in living standards in the West cannot be understood without understanding the tendency for the rate of profit. And surely, no society can survive the systemic impoverishment of its workers for any length of time, at least not if it wants to rule by consent. But alongside this we have global warming, the march of the algorithms imperiling countless jobs and of course the growing struggle over economic hegemony as the US struggles to maintain its grip on the world economy. (Against the background of COP26 I find it disgusting that while Biden pledges support to reverse global warming, US imperialism continues to encircle China and repurpose its nuclear arsenal and delivery systems including now its F35s.)

I support the characterization of Twilight Capitalism because capitalism is aglow with white hot contradictions. The confluence of all the issues described together form an insoluble whole which capitalism cannot manage. Even if capitalism could survive an elevated composition of capital it cannot survive these converging and compounding issues all at once. The 2020s in my opinion is the decisive decade for humanity on all fronts. And so the outlook for the political weather after taking everything into account, is set stormy.

Retired science teacher button pushed, sorry. The Earth is closer to the sun when it is winter in the northern hemisphere. The effects of axial tilt are more important than the effect from the ellipticity of the Earth’s orbit. Yes, this also means the Earth is both closer to the sun during the summer in the southern hemisphere) *and* the southern hemisphere is tilted toward the sun, absorbing more energy. The last time I looked it was believed the larger proportion of ocean in the southern hemisphere moderated the rise in temperature.

Finally, the critique of Robert Brenner is the other aspect that intrigues me, as I have been pursuing a critique of the same from the historical materialist side with respect to “The Origin” of Brennerism. That is a play on the central historical fixation of his school, “The Origin of Capitalism”, said to be only in England, only in its agrarian sector, between 1400-1560.

The intriguing part is that the book appears to argue that Brenner’s contemporary economic analyses are “neo-Smithian”, via Keynes, apparently. But with the assistance of especially Neil Davidson in his “How Revolutionary were the Bourgeois Revolutions?”, I’d argue that Brenner’s and his follower’s historical theory is precisely a “neo-Smithian” account of the rise of modern capitalism hinged upon their concept of “market dependency”, itself derived from the displacement of Marx’s concept of social relations of production and forces of production, with “social property relations”, the replacement of relations between human actors engaged in necessary production, with the relation of actors to “things”. A classic reification, IOW.

In any case, I had always wondered on the relation of Brenner’s historical theory with his contemporary economic analyses, and regardless of other objections, this may be it. Brenner got by both ends!

““The Origin of Capitalism”, said to be only in England, only in its agrarian sector, between 1400-1560.”

That’s not Brenner’s historical thesis. Not only in England, but yes beginning in the agrarian sector given the fundamentally agrarian organization of society AND the critical, essential relationship that defines capital, the separation of the producers from the instruments of production.

Marx says that a certain level of agricultural productivity is the fundamental condition of historical development. Brenner uses that insight by Marx as a lens to examine England, and he asks the question “what conditions in the English countryside precipitated this heightened productivity that supported the urban areas, allowed Britain to embark on the Industrial Revolution before other countries and more completely than other countries.

Brenner’s historical work is, IMO, valid, valuable, and usually attacked because his audacity in locating the social relation of production that defines in capital specifically within social relations and not in “flabby” concepts like “wealth” “world systems” or misapprehensions of primitive accumulation.

Judging from my reading of Ellen Meiksins Wood, strongly influenced by Brenner, the agrarian origins thesis is far too narrowly focused. Expropriation of church lands are radically deemphasized, in favor of market relations seen mostly as cash exchanges, abstracting from ownership. Merchant capital is improperly assumed to not be capitalist at all. Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Redeker have usefully pointed out that wage labor in shipping anticipates the factory, complete with class struggle. And of course the narrow national focus obscures the structural exigencies imposed by the need to support an army and defend a frontier. The rise of English capitalism owes much to the lower cost of land forces and the greater power of the high-skill labor of sailors. Brenner/Wood are too schematic, too detached from concrete reality in my view.

Neil Davidson looks like an attempt to explain how “bourgeois revolutions” weren’t really revolutionary. This is a common ploy, as witness the earnest attempt to declare the American Revolution was actually a counterrevolution!. In the US the historical precedent is the equally earnest attempt to reduce the US Civil War, the second bourgeois revolution, into a mere rebellion, if not a counterrevolutionary crusade. In some versions the abolitionists are downright “Stalinist” in the totalitarian aspirations, but in all such the social discipline is equated with tyranny. This is more anarchist than Marxist. The basic impulse I think is to peddle illusions in bourgeois democracy *now*, when we, the enlightened people have got it right….not least because we have purged the totalitarians from our midst (the McCarthy era) and from the world (the great crusade culminating in victory when the USSR fell.) I would be interested to know if there’s really more to him than that, but that kind of book is not easily found outside an academic library (if it is there.)

The review of the book, and presumably the book itself, make the case for recurring crises in capitalism, a profit problem. What is not shown is that capitalism has arrived at its twilight. Indeed it has; it just has not been explained here.

As for China, the summary quotation is a series of conclusions. If the authors have evidence and logic for them, the review gives no indication. “The thesis that China has been completely reabsorbed into world capitalism, that the Chinese party-state bureaucracy is now an instrument of capitalist class rule and that the Chinese economy is subordinate to the law of value is simply not credible.” Anyone familiar with the mad scramble for profit in China by state-owned firms, city and provincial governments, and private corporations, and anyone familiar with China’s export of capital (number one in the world) and plentiful accounts of typical monopoly capitalist depradation, would say just the opposite is credible.

It is funny when modern “Marxists” believe the Chinese state is somehow socialist (or “socialistic”). Obviously, the state party appropriates and controls workers’ surplus and the workers are given a fraction of the surplus they create back in the form of a wage. The workers do not control their lives in any meaningful sense anymore than workers in the west do.

It seems one of three things generally occurs with these Marxists: (1) they are unable to distinguish between ideology and material reality, as the brutal Chinese state is as pro worker as Trump is a Christian, (2) they are unable to see the historical need for these nations to develop nationalistically, that is, as a nation run as one walmart, rather than subjecting themselves to the many walmarts of foreign capital, and (3) they often envision themselves as the intellectual martyrs here to liberate the working class vis a vis nationalization and concentration of power in the (capitalist) state.

“What’s more, to credit China’s rapid economic development and modernization to the restoration of capitalism is to give considerable ground to those who reject the Marxist thesis that, by the twentieth century, capitalist social relations had become a brake on the development of the productive forces of humankind.”

The authors are again confused. To say that capital had become a fetter on the productive forces in Europe during the 20th century is plainly obvious – this is what an economic crisis IS. That one way out of this crisis was for capital to absorb billions of human beings across Asia (and that this led to another wave of accumulation) is also true.

Workers in the 21st century will have to take control of their own lives and create a rational society in their own image. This requires workers in China reject the Chinese state to the same degree that American workers reject the American state: Wholesale.

Praising a nation state? Some Marxists!

” Obviously, the state party appropriates and controls the workers’ surplus and the workers receive a fraction of the surplus they create in the form of wages. Workers do not control their lives in any meaningful sense any more than workers in the West. ”

Exactly. Are we not then in front of a new ruling class (the Communist State Party both in China and in the rest of current and former socialist countries) that extracts surplus value from the workers just like the capitalist class of any country does? Chinese workers, the vast majority of workers who are not part of the 95 million of the Communist Party, do not have, among other benefits, a guaranteed job for life. State workers do. Chinese workers, and the rest of each country, suffers extraction of surplus value by their capitalist class and suffers it by their State. Obviously, it only has one solution, stated in a simple way: socialist state under command, domination and control of its workers. Socialist states in cooperative and common property. This situation of democratic socialism will be reached as the socialist mode of production is built (step by step and through revolutionary impulses) but that is another issue.

Incidentally, in current socialist studies there is a lack of those who dedicate themselves to analyzing states in depth: whether or not they obtain surplus value, how they achieve it, and, especially, whether they are companies with a decreasing rate of profit or not. I have the suspicion, unsubstantiated by any study, that modern states (socialist and capitalist) are far from having a decreasing rate of profit. In my opinion, the economic subject that produces 40/50% of the annual production worldwide deserves this analysis. That economic subject (the State) is not “outside” of Capitalism. It is inside and is its main actor. In the XIX century of Marx and Engels the States were dominant but small companies (about 5% of GDP) but today it is not like that.

A small and last addition on my question only the possible decreasing Rate of Profit of the States. The great and priceless work of M. Roberts and other authors on this rate in capitalist firms has scientifically and empirically demonstrated the decreasing (average) rate of profit of Capitalism. This decreasing rate, like other theses (cycle of class struggle, etc.), predicts and supports the decline and end of Capitalism. Well, in my opinion, the same empirical study on the States themselves remains to be done.

As far as I can see, the argument is that the falling rate of profit is the cause of crisis in capitalist economies.

If this characterization is correct, and given that the rate of profit has been almost monotonically in decline for decades (according to data herein provided regularly), should it not be the case that capitalist economies are always in crisis?

I would say capitalist economies are not always in crisis. There are periodic crises yes, but not permanent crisis.

If that is the case, then the argument central to the Marxist theory of capitalist crises cannot be valid.

Perhaps my idea of crisis, in the Marxist sense, is flawed?

What have I missed?

Marx never argues that crisis is a permanent condition of capital. Only that it is latent, immanent, within the relations of capital itself. Crisis for Marx is always a short term disruption, while the falling rate of profit is a long term tendency, and always accompanied by offsetting tendencies. Those “tendencies” form the basis for class struggle.

OK, thanks for clarifying that.

I would say that adds fuel to my fire.

What that says to me is that this tendency is not the cause of crises. The cause is more local in terms of time.

Having had a career in the equity markets, I witnessed first hand many financial market melt downs, a couple very serious. It seems to me that the sort of dynamics that applied were those described by Fisher (Debt Deflation) and Minsky where animal spirits take an exponential turn financed by crazy debt arrangements.

The Great Depression came at the end of the great technology boom of the 1920s. Over-investment (irrational exuberance) was well in evidence and then the Federal Reserve removes the party punch, to be exacerbated by the exigencies of the gold standard, the Smoot–Hawley Tariff, etc..

I can’t see that the secular tendential fall in the profit rate had anything to do with these crises.

A minor point on the care with which we need to use words: Why do even we – marxists – refer to income ‘earned’ by the top 1% or the bourgeoisie in general when we should be using the expression ‘income accruing to’ or income appropriated by’ these elements? Calling income appropriation from surplus value, in whatever form, as ‘Earning’ seems a bit contradictory! I am not being pedantic, but it is important that we see the point being made, even if it is not a terribly significant one.

Venkatesh Athreya

Michael’s book review brings up important aspects that are scientifically (that is, by analyzing facts) supported and justified. But then come the “modernizers” who spread their opinions without facts or data. That is Twilight Marxism.

“Indeed, the expansion of robots to replace labour in production will accelerate that.”

Yes, if there is anything I agree with here it is that.

Technology (robotization and AI) will take us to the point where labour will be virtually totally dispensible.

The problem will be how to distribute production if labour is not involved in its production?

Who will be able to purchase society’s produced output – not labour – and the capitalists can’t consume all of their production.

In effect, ironically, capitalists will have no incentive to produce.

Capitalists could be contracted by the state to organize production (or it could do it itself), allow the capitalists a return and distribute output according to a rule – according to one’s ability or one’s needs or a combination of both – a blended socialism/communism without tumultuous revolution.

“Technology (robotization and AI) will take us to the point where labour will be virtually totally dispensible.”

Not under capitalism it won’t be. If there is no necessary labor, then there can’t be any surplus labor, and thus no surplus value. What will occur is a persistent devaluation of labor power– we have seen that since the 1970s with increases in temp work, part time, precarious employment, low wages, reduce benefits and protections– the creation of a more disposable labor force.

Old story. After Ford was unionized, Henry took Walter Reuther on a tour of the Rouge plant in Detroit. With pride he showed Reuther an experimental production line where the work was being done by machines and only machines. Said Henry to Walter: “When this becomes a reality, Walther, who will you organize?” Walter thought a second and replied “When this becomes a reality, Henry, who are you going sell the cars to?”

That’s one way of putting it. The point being the whole basis for market relations collapse once workers are no longer compelled to use labor power as a means of exchange

A-C,

“The point being the whole basis for market relations collapse once workers are no longer compelled to use labor power as a means of exchange”

That’s exactly what I was saying – so I totally agree.

But capitalism will not suffer a death because of the decline in profitability but because of technology.

The increase in technology across the mode of production is the essential trigger for the tendency of the rate of profit to decline. This long term tendency does NOT doom capital out of hand, as there are offsetting tendencies, but those offsets require driving wages below the reproductive cost of labor power. Now that can take the form of the migration of capitals to low wage countries, the growth of “special enterprise zones, the reabsorption of pension funds into the corporations’ own financial account, the none payment of wages, and wholesale shutting of factories as happened in the Guangdong during the 2008 meltdown. These are relatively “benign” attacks designed to reduce the wage below the cost of reproduction. Other not so benign ways are slave-like conditions, extreme exploitation of migrant labor etc.

Short version: Nothing condemns the capitalist mode to a death without the actions of a class organizing itself as the executioners of that mode.

A-C,

I am sorry but I think you have totally missed the point, even having recited the Ford-Reuther story.

There is no question of seeking out low wage markets. There is no question of having to employ labour, anywhere.

Technology has advanced to the point (ironically, probably under the aegis of capital) where labour is dispensible and capitalists have no mechanism for dispensing their output.

Marxist principles are completely subverted.

“I am sorry but I think you have totally missed the point, even having recited the Ford-Reuther story.

There is no question of seeking out low wage markets. There is no question of having to employ labour, anywhere.

Technology has advanced to the point (ironically, probably under the aegis of capital) where labour is dispensible and capitalists have no mechanism for dispensing their output.

Marxist principles are completely subverted.”

Well, it wouldn’t be the first time I missed the point, but if your point is that now “labour is dispensable, and capitalists have no mechanism for dispensing their output…” ummh….that’s sort of the key to capitalist development– expelling labor power from the production process, substituting technology. That process is also associated with expanding markets, not shrinking markets, and finding and creating more “mechanisms” for dispensing output. Example? Look at the development, not just growth, of container shipping since 1960 and the “imbalance” between the technical and “living” components of that process. Now this process is not “even” or “linear.” Overproduction in container shipping has been an enduring part. But nevertheless the disruptions, expansions, contractions completely confirm Marx’s analysis rather than subvert it.

Here’s what you’re missing, and what Reuther was missing, in the parable about automation. Ford will indeed be able to claim surplus value in the markets, even if “his” contributions, his commodities contain NO surplus value. Ford will claim portions of the surplus value brought into the market by all other producers, and he will receive that allocation through the price mechanism. The production of the Ford models at below the average socially necessary labor time will be “compensated” in the market by transfers of surplus value from GM, Chrysler, etc etc.

What you think is the “death” of capital due to technology is in fact a distortion of the reason the rate of profit falls. However, there is no fall in that rate that does not compel the owners of the means of production to search for and impose offsetting tendencies, the devaluation of both the means of production and labor power to preserve the overall capital relations.

Capitalism will suffer a death only when it is executed.

A-C,

“Ford will claim portions of the surplus value brought into the market by all other producers, and he will receive that allocation through the price mechanism.”

But there is no value – there is no market for the output because no-one has the income to buy the output – there is no price mechanism.

And why would capitalists produce that output if there is no market for it?

(And I will probably end my discussion here given that the totalitarian powers that be might consider I have broken an undertaking to them even though that undertaking in my mind only related to political polemics. :-))

“Technology has advanced to the point (ironically, probably under the aegis of capital) where labour is dispensible and capitalists have no mechanism for dispensing their output.

Marxist principles are completely subverted.”

No, Marxist principles are completely vindicated. Have you ever even read Capital Volume III? I know you like to bash Marx in the comment section here but you clearly don’t know much about whom you bash. According to Marx capitalist accumulation and competition necessitates technological development that increasingly renders labor redundant the exact process that you are describing.

Darren,

“… you clearly don’t know much about whom you bash.”

Yes you are correct.

I have attempted to read Capital and Grundrisse several times but I find them too turgid and repetitive to the point it becomes confusing. Its like struggling thru a morass of intellectual treacle.

It is my understanding that Marxist principles are based on the relations of production.

If there is no labour in production there can be no “relations”.

Henry You want to learn more about marxist economics but think socialism is a waste of time. I am not sure why you are bothering with this comments section then. You find Grundrisse and Capital (of which you are an expert, it seems) turgid (the phrase that Keynes also used about Capital). Perhaps you might find Hadas Thier’s book, A People’s Guide to Capitalism, easier to digest. Why dont you read that before hitting the comments page again?

Darren,

” I know you like to bash Marx…”

I wouldn’t say that – I am interested in understanding Marxist economics.

I do like “bashing” socialists however given I think you would have to be crazy to be a socialist given the history of socialism in the 20th century but I have undertaken to desist from this “bashing”.

Michael,

Today I read the online appendix to Smith et al’s book. It was an eye opener for me to see how Marxists distinguish between Stalinist bureaucracy and worker’s soviets. I admit great ignorance about these matters. It was interesting reading.

I will purchase Thier’s book and I also intend purchasing Smith and co’s book.

And as far as Grundrisse and Capital being turgid and longwinded is concerned, I’m afraid this is how I find them. For me, they are very heavy going.

Henry,

Having recently read Capital vol. 1 and Grundrisse, I can understand your difficulties, but there may be several reasons for this, the most important of which I think could be Marx’s extraordinary method of actually tackling the problem – how to deal with an ever-changing system comprised of interacting phenomena across a range of spatial and temporal scales. His solution was dialectical materialism combined with a remarkable flexibility in abstraction. This might be the “morass of intellectual treacle” you referred to, but persevere because it’s enormously powerful. The method was utterly revolutionary at the time – kind of like applying chaos theory in the study of weather systems instead of using seasonal averages – and even today, it’s an approach that is rarely used and poorly understood, if at all. Today, unfortunately, idealism and what can broadly be called the philosophy of external relations still dominates. Anyway, as an ecologist, I was mostly dumbstruck by Marx’s Capital. Here was a 19th century bloke writing about and applying what I had come to know as systems theory or more broadly, ‘Earth System Science’. Chaos, interaction, feedback, emergence – it was all there in Capital. And rather than apply dialectical materialism to nature (as Engels later did), Marx applied it to history and society. Holy s**t! And here I thought all this stuff about tipping points, systems analyses, systems thinking only began in the 20th century. For this reason alone, Marx’s Capital is worth studying. Sure, read it through as you might any other book, but then go back and study it. It’s an effort that will pay you back many times over; far more than reading someone else’s interpretation Capital. And what you learn, for example, is that socialism – which is a process, not a thing – is inherent to capitalism. What I, you or anyone else might think about socialism is irrelevant. It’s there as soon as you have capitalism, for the simple reason that ALL processes have inherent contradictions, whether an organism, cyclone, ecosystem, economic system or society. Contradiction is neither good nor bad, but simply part of change itself. It’s the motor force of change. In capitalism, there is the contradiction between capital and labour, for instance, or value and use value. These and others lead to exploitation, inequality, racism, monopolies, economic instability, environmental destruction. The majority of people of the world don’t like these inherent attributes. We want something else, something better and we tend to call this ‘something better’ socialism. Is this ‘crazy’? Put less ideologically, capitalism WILL change into something else, for the simple reason that capitalism’s inherent contradictions will not go away. We can ignore them and perish – global warming and nuclear war are good candidates here – or rapidly dismantle this system and give ourselves a chance.

Henrik,

” ….kind of like applying chaos theory in the study of weather systems instead of using seasonal averages…”

This is very strange and interesting. I was thinking about this the other day.

It occurred to me that reading Marx was like trying to understand a weather synoptic chart.

His arguments seem to swirl around a centre and seemingly disappear into a central vortex of ideas only to appear somewhere else and as they swirl they suck in other arguments but somehow the whole body of thought seems to move along in a particular direction. Occasionally, a prominent theme (a weather front) sweeps in and adds extra impetus to the argument.

Henrik,

“Put less ideologically, capitalism WILL change into something else, for the simple reason that capitalism’s inherent contradictions will not go away. ”

I vaguely understand the argument.

However, just as capitalism is seemingly about to implode, a rabbit is pulled out of a hat.

Someone like a Keynes comes along and injects a measure of good sense, humanity and decency into the system, much to the chagrin of socialists.

It was encouraging that there were people who bought the line – however for the last few decades the counterveiling forces have been in ascendancy.

Perhaps there are only so many rabbits that can be pulled from the hat.

I’ve followed these exploratory contributions happily noting the new learning which is welcomed. But clarification is always desirable. Firstly however, contradictions do not stay the same! Well, not in the real material world, no matter that their mental reflection into ideas may remain fixed in some minds.

Those guided by a Marxist worldview will constantly and consciously interrogate and re-examine the objective external situation as it moves and changes, thus acquiring a deepening cognition through the flow of material and mental interactions. This is critical thinking, the modus operandi of human ideological development.

It seems appropriate to make the simple point that we call these reflections ideas. And to examine the nature of ideas we may study the process by which they arise and develop, and occasionally become discarded: i.e. ideology as a historical phenomenon. Thus we may develop new words to describe our deepening understanding. Hence we accept new terminology, it makes the process easier to share.

Looking at the economic history of capitalism shows a tendency to implode from time to time. This can be understood as a tendency for material contradictions to become extreme and to become violently resolved into a new set of contradictions, We name this critical process a crisis. We can also define this crisis as a process of negation. Negation can be understood as the mental reflection of the actually observed real material change.

As for pulling rabbits out of hats, this is a trick performed by members of the Magic Circle in an entertaining routine of deception and misrepresentation to amuse and amaze, in other words, to fool the audience.

I could be trite and accuse Mr Keynes et al of such a trivial pursuit, but sadly, they were deadly serious! They really believed in their own bullsh!! With deadly consequences for millions of others! Bretton Woods lasted only 25 years. Admittedly, twice as long as the crazy 1.000-year prophetic ravings of that other economic lunatic, A. Hitler.

“Humanity and decency” for real people came a very poor – and very distant – second to corporate profitability – even in the fantasy world of Keynesian and Friedmanite imagining. Fictitious profits which “seemingly” emerge out of fictitious capital “investment” do create something real, however! Out pops a new set of material contradictions which have transformed the processes we have now renamed as Neoliberal Capitalism. That, which has now been in a phase of critical decomposition for half a century.

It may help to understand these new contradictions by referring to the satirical rabbit-hole conjured up by Lewis Carrol. That great anticipatory work, like those later efforts of James Joyce and Flann O’Brien, have warned us against taking seriously, the nonsense conjured up by professional deceivers and misleaders bent on stupefaction (the “bringing into line” of millions of lazy minds).

What should be stressed is the unity of that literary opposition between the world imagined by our great trio of satirists and the sober work of scientists exploring the nature of our universe. Both can assist in our creation of a more authentic worldview, but we must learn to distinguish between these two contradictory opposites by deepening our understanding of the nature of the evidence presented as dying capitalism descends into such tragic chaos in its process of negation into …

Well, will is be C21 Socialism? And what will that be like? That will depend to a large extent on us getting real and respectfully constructing a real democracy among 7.9 Billion equal humans. But we can be quite sure that won’t be built on lies, naïve misunderstandings, and/or misrepresentations.

realdemocracyinireland

Like a good little student I am progressing with the homework assigned by the powers that be. ( And I am feeling self-satisfied given that Smith and Co admitted themselves that Marx’s writings are difficult and dense.)

I am looking forward to sorting out this notion of “contradictions” and how they resolve.

Keynes was firmly wedded to his class so he was no (social, political) revolutionary. But he was, as you know, determined to save capitalism from itself. How his new approach to macroeconomics was used/abused can hardly be put at his feet. Nor can he be lumbered with the responsibility for the development of the rapacious form of capitalism we see today.

I keep reading about how socialism is synonymous with democracy. Having been around when 20th century socialism was in its heyday, I find it impossible to reconcile with this notion.

“Given that the rate of profit has been almost monotonically in decline for decades (according to data herein provided regularly), should it not be the case that capitalist economies are always in crisis?” You expose a flaw in the chatter by some of the people who talk about the falling rate of profit: in a crisis, capital values are destroyed. Capital assets become worthless. This destruction reduces the denominator of the rate of profit, s/(C +V).

The cycle has gone on for about 200 years of capitalism. Obviously, there must be a different explanation for the historical moment when, as Marx foresaw, “From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into their fetters.” In this case, the relations are the basic capitalist relations. In the U.S. this moment began around 1973, and as many have observed, the real median wage has stagnated and declined ever since.

Similarly, new technologies have made existing one obsolete for centuries. This process by itself cannot explain the historical moment at issue.

The explanation is in the interaction between capitalist accumulation and a new kind of technological development. See The Hollow Colossus.

I was not intending to comment on China. But I have to warn comrades who refuse to identify China as a capitalist state you are on dangerous grounds. Please follow this link to the recently released Pentagon assessment of China https://media.defense.gov/2021/Nov/03/2002885874/-1/-1/0/2021-CMPR-FINAL.PDF There you will find the Pentagon artfully cutting and pasting every declaration and proclamation by the CCP and its leadership that China is socialist. In the coming conflict with China, not only will this be a war over democracy but one between socialism and capitalism, with capitalism being the good guys.

Marx taught us how to categorise societies not by investigating their superstructures but by analysing the manner in which the labour of the individual is transformed into the labour of society and how that labour is appropriated. In China the labour of the individual only becomes part of the labour of society indirectly through being exchanged first and that labour is always appropriated by the employer. It is a regular market economy driven by profit and accumulation. Once this is fixed in consciousness, there is no problem recognising that super-structurally, capitalist societies can range from ones governed by proportional representation to fascist to ones even with Chinese Characteristics.

Thus categorising China is not merely an academic exercise but a fundamental political one with the most profound implications for programme and tactics.

Many thanks to Michael Roberts for his generous assessment of Twilight Capitalism and his incisive summary of many of the book’s principal arguments. As expected, the review has elicited a good deal of interest and commentary. It would be thin-skinned of me to respond to all the negative comments, which more often than not display a good deal of confusion about how the book characterizes capitalism’s “twilight,” as well as its defence of Marx’s law of profitability and our view that China is a transitional social formation worthy of defence against world imperialism. Most of the objections raised to our analysis, theoretical positions and research methods are actually addressed in the book, so we will leave it to those who read it to cast judgment on how adequately we’ve done this.

Michael has provided a link to the publisher’s page for Twilight Capitalism at the beginning of his review, and I urge everyone to explore the contents of that page, which includes a link to an extended excerpt, as well as some important digital appendixes to the book. Here’s the link once again:

https://fernwoodpublishing.ca/book/twilight-capitalism

Murray E.G. Smith

Brock University

“China is a transitional social formation worthy of defence against world imperialism.”

Could you elaborate on the elements of such a defense? How in particular a defense of China from imperialism differs from, say, a defense of Iraq or Iran from imperialism?

In the sense that the defense of the Soviet Union before and during world war 2 would have been anti-imperalist. Iinstead the allies’ supported nazism during its rise and rearmanent and followed that with their pretend war in Europe revealed their anti-communist, imperialist nature. Similarly, non-support for the Chinese “state” reveals an idealist, imperialist bias. Lenin defined the Bolshevik state as “state capitalism”.

I should have added to the above that US/NATO’s interventions–not only their criminallly detructive ones in Yugoslavia, Iraq, Syria, Lybia, etc are almost by definition imperial, but so are the US sanction regimes and its color revolutions against “authoritan” in favor of fascist regimes.

correction: “supported” in the second sentence of my original comment should be “support”.

There’s a gross misunderstanding in this comment section about the status of China as socialist.

The cliché that states China has become capitalist after Deng Xiaoping’s reforms is a distortion of History that comes from the idealization of the Soviet Union. It only stands any logical ground if one considers the Soviet Union as the holotype of socialism.

The thing is: History does not progress in a straight line. We know with the benefit of hindsight that the Soviet Union was not the holotype of socialism because socialism, in the historical sense, socialism is the successor of capitalism, therefore concluding otherwise would lead us to the conclusion socialism cannot ever ultimately succeed. From this, either you fall into the fallacy of Western Marxism, which degenerated into a messianic cult during the post-war period, and keep stating socialism can only come in a single and sudden event, a textbook revolution that will destroy capitalism in one shot; or you go liberal and adopt some variation of “End of History” hypothesis.

We can take the example of capitalism: we know – also with the benefit of hindsight – that the original capitalist empire – Portugal and Spain – were not the holotype of capitalism. They were transitory states. The holotype of capitalism turned out to be England.

The most likely scenario is that the historical role of the Soviet Union was just as the first experiment of a proletarian government. It served the purpose to convince the working classes that it was possible. It is highly unlikely all the variables that aligned in Russia 1917 will ever align again, so socialism will have to come from another route.

We can attest this from the documentation of the 1910s and before: Lenin was not considered to be an orthodox Marxist by any stretch by those who considered themselves to be the true heirs of Marx (the German Social-Democrats). It was only after October, and only after the revolutionary attempts in the West failed spectacularly one after the other that Leninism became enshrined as the Marxist Orthodoxy applied to politics, and the October Revolution enshrined as the holotype of communist revolution.

To say the USSR is the model for socialism and communist revolution is, therefore, pure revisionism. It is objectively false.

Now, it doesn’t mean the USSR was a farce. It more than justified its existence because of what it would give birth to in Asia (and because they destroyed the Nazis – that’s the crucial point Western Marxists to this day don’t understand Stalin, but that’s another topic).

When the USSR was born, the Bolsheviks had a dual policy: for the advanced capitalist states, immediate communist revolution (i.e. immediate transition to socialism); for the backwards and colonial regions, first a bourgeois-democratic revolution, then a proletarian-socialist revolution. The key here is the development of the productive forces: the Bolsheviks never had any illusions socialism was feasible in the colonial world and Russia’s Central Asian provinces. The role of the bourgeois-democratic revolution as the developer of the productive forces was enshrined and consecrated in Comintern.

The Communist Party of China followed the instructions of Comintern to the letter (and paid a heavy price for this in the first decades of its existence). It was only after Mao’s ingenious interpretation of the Comintern line that the CPC really started to get going.

Mao’s interpretation was brilliant: he (correctly) analyzed that the long historical phase of capitalism where the bourgeoisie actively promoted the development of the productive forces was over. The imperialist phase of capitalism in which he now lived was characterized by the opposite in the colonies: the undermining of the development of the productive forces was the policy of the global bourgeoisie. The colonial world had thus a comprador bourgeoisie.

He then concluded (also correctly, as History tells us) that the role of socialism, in the colonial nations, was to do the proletarian-socialist revolution outright, and absorb to itself the historical task the bourgeois-democratic revolution had in the imperialist world.

So, the CPC not only is a true Marxist-Leninist party, it may be in fact the last bastion (alongside the Communist Party of Vietnam, which has an identical doctrine) of Comintern in our present times. China is a socialist nation, if not for the simple fact that it is the one that stands nowadays (Marxism in the West is essentially in extinction, there’s no chance of any communist revolution there), successfully inheriting the torch left by the USSR.

I hope this is not in response to what I wrote. I’m in almost perfect agreement with you. Maybe all those typos annoyed you….

Karl Marx did not analyze capitalism on the basis of government declarations or party programs, but rather by uncovering the special production of wealth, that is, the private appropriation of unpaid labor. “Wage work always consists of paid and unpaid work.” K. Marx, Grundrisse der Critique of Political Economy, 468.

Wage labor is also the basis of the Chinese production method. Some of the unpaid work is appropriated privately by capitalists, while some of the unpaid work is appropriated by the state. In no case are the workers the masters of production. I think the Chinese way of production still has historical justification. As Marxists we have the mission to eliminate wage labor. But this mission necessarily relates to one’s own country. We cannot and must not dictate to the Chinese what they have to improve in their country. We have to sweep our own front door.

Wal Buchenberg, Hannover

https://marx-forum.de/Forum/

The term holotype evokes notions about the eternal essence of species. Decades ago Robert Heilbroner disingenuously wondered why Sweden wasn’t as typical a capitalist state as the US. The answer of course was that the US is in itself a significant proportion of capitalism, hence more typical than Sweden. Thus, neither Portugal and Spain were not the first capitalist states. Even the Italian city-states were more capitalist. Further the expropriation of Church lands to be truly integrated into capital markets for land were an indispensable aspect to the rise of capitalism. Empires existed before capitalism and are not defining.

As to the alleged fallacy of “Western Marxism,” when socialism does come to the metropoles, it will be “overnight” precisely because of the highly developed productive forces permitting, even requiring it. I have no idea why anyone still expects that the mightiest citadels will fall first however. The capitalist world includes India, Brazil, South Africa, Russia, indeed most of the planet. The idea there is no chance of socialist revolution in the “West” is absurd. The obsolescence of Marxism and the supposed failure of its “predictions” is as illusory as the glorious success of capitalism. It’s true that capitalism+social democracy is a chimera, doomed to die even if it could somehow be born. If that goal is “Western Marxism,” then yes, “Western Marxism” is doomed. But this is uncomfortably like the Common Prosperity.

In practice, every single workers’ state, including those in central Europe, Cuba, Vietnam and Korea, as well as China did not slavishly ape the USSR, not even those set up by the Red Army. Notably, Poland did not collectivize agriculture (one reason it is so backwards today,) for example. The tremendous power of the Soviet lead was due to its successes, not servility, not even stupidity.

Mao’s New Democracy committed to the proposition there was a national bourgeoisie and that there would be a transitional formation. The objection of the Dengists, including so far as I can tell, Xi-ists, is that Mao didn’t keep his word. They hate him for that. The carefully limited expression of that hatred is due solely to the fact the unrestrained attack on Mao is an attack on the very independence of China. Mao himself is censored. His collected works are still too inflammable to publish! The argument Mao was a stealth Trotskyist is interesting, but not widely accepted.

It seems pretty unlikely the CPC would have gotten far if it had opposed the Guo Min Dang from the beginning. It seems equally unlikely that the CPC wouldn’t have benefited from breaking with the GMD long before Chiang Kai-Shek (Jiang Jieshie) knifed the Communists in the back. But the truth is, it is by no means certain that only the Comintern kept the CPC from victoriously overthrowing the GMD, the warlords and imperialism in 1927. The assumption that it was the CPC’s victory is like those analyses of Gettysburg that omit the role of the Yankees.

Like the bourgeois state, the workers’ state is an instrument of class rule. The achievement of bourgeois democracy, which surely includes universal manhood suffrage, including women, was not complete till the twentieth century! The transition to socialism will be extended. There is an infamous scandal about one Michel Pablo saying there might be centuries of deformed workers’ states. But it is completely idealistic to insist that the new world could be born free of defects, complete with the final form of socialism. Since it is not even known what that will be, as all the peoples of the world will have contributions to make, insisting on the ideal state is in fact substituting a quasi-messianic faith for serious analysis. The critics of socialist countries are the religious believers, projecting their own failings onto others.

PS The first definite proletarian experiment in state power was the Paris Commune.

Declining powers seek war to preserve what remains. Ascending powers tend to avoid wars unless it is forced on them. That is the general law governing the imperialist epoch. It is clear that the declining US is the aggressor today having sited 400 military bases around China . We oppose US aggression for what it is, not because China embodies transitional forms worth defending.

The moral critique of imperialism is irrelevant, because the mass of the people do not determine such policies. Even if your program of moral enlightenment swept the masses, nothing would really change. Indeed, your approach really implies there is no need for socialism at all. Obstreperous tactics like shouting “Socialism!” interfere with reforms. To engage in violence is evil too, hence the implicit need for socialists to support liberal democracy. (Yes, this includes invasions, armed subversions, assassinations, bombing, economic blockades of whole nations.)

Also, I don’t think anybody really accepts this kind of logic. The Assad government in Syria stood for a secular national government, against religious government. As near as I can tell, the program was to kill all the Alawi who were supposedly the bad people propping up Assad. Yet socialists of your kind almost universally supported this! (I don’t actually know of any exceptions but that may just be my ignorance.)