The semi-annual meetings of the IMF and World Bank start today where finance ministers and central bankers will meet in slimmed-down but in-person gatherings in Washington. This meeting is likely to be overshadowed by the scandal involving the IMF chief Kristalina Georgieva, who may well have been forced to resign as I write after a devastating report on the machinations of senior World Bank officials several years ago. Georgieva has been accused of manipulating data on ‘Doing Business’ to favour China, Saudi Arabia and other states while she was at the World Bank several years ago. The scandal has divided IMF members, with the US pushing for her to go and European powers wanting her to stay.

But more important than even whether we can ever rely on the scientific honesty of the World Bank and the IMF is what is happening to the world economy as these international agencies meet to review progress on the recovery from the pandemic slump in 2020.

Earlier in the year, most mainstream forecasts for growth, employment, investment and inflation were bullish, with hopes for a V-shaped recovery based on the COVID vaccination rollout, the ebbing of the virus cases and the boost to many economies from fiscal spending by governments and injections of credit by central banks. But in recent months, that unabashed optimism has begun to fade. Just before IMF-World Bank meeting, Georgieva reported that “We face a global recovery that remains “hobbled” by the pandemic and its impact. We are unable to walk forward properly—it is like walking with stones in our shoes!”

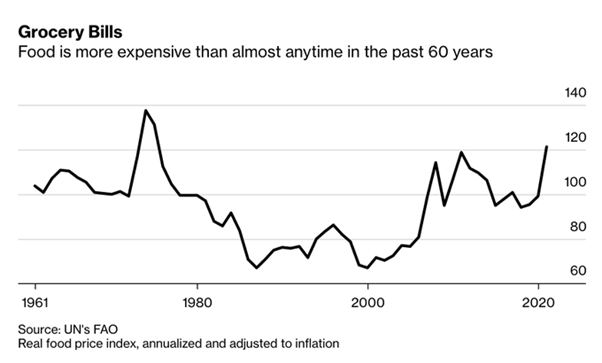

She outlined the three stones in her shoes. The first was growth. At the meeting, the IMF is set to lower its forecasts for global growth in 2021 and expects the divergence between the richer Global North and the poorer Global South to widen. The second was inflation: “One particular concern with inflation is the rise in global food prices—up by more than 30 percent over the past year.” And the third was debt: “we estimate that global public debt has increased to almost 100 percent of GDP.” (No mention of private sector debt, which is much more important and at historic highs).

Georgieva posed the risk of what is called ‘stagflation’, ie low or zero growth alongside high or rising inflation. This is the ultimate nightmare for the major capitalist economies – and of course, the worst possible scenario for working people who would bear the brunt of rising prices for households while income growth remains weak; leading a fall in real incomes.

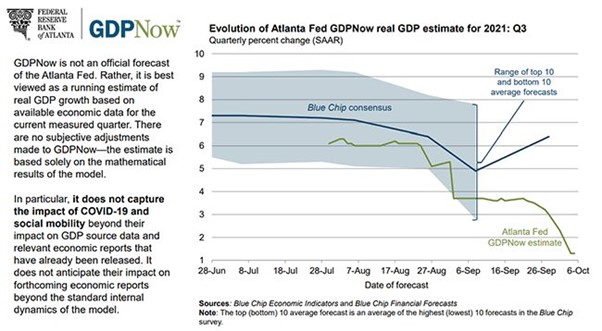

This was the story of the 1970s. So is stagflation coming back in 2022? Let’s look at the GDP growth side first. The evidence is building up that the ‘sugar rush’ recovery in the major economies after the end of the pandemic lockdowns and after the impact of fiscal spending and easy money is flagging. For example, in Q3 2021 just ended, the Atlanta Fed GDP Now! forecast for the US economy suggests a sharp slowdown (compared to consensus calls) to just 1.3% annual rate. And Q4 is likely to be worse. After the ‘sugar rush’ comes the fatigue.

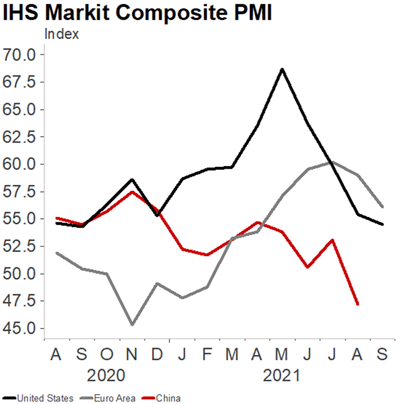

The ‘high frequency’ business activity surveys called the Purchasing Manager’s Indexes (PMIs) are also showing a distinct slowdown in most regions from the peaks of the summer.

And in the US, the latest official data showed the jobs recovery stalled for a second consecutive month in September. Coupled with lower business and consumer confidence, this suggests the ‘sugar rush’ there is also over. In China, the government is grappling with sporadic outbreaks of the Delta coronavirus variant and the risk of a property debt implosion along with an energy shortage. Strong growth over the summer appears to have slowed sharply in the eurozone and UK.

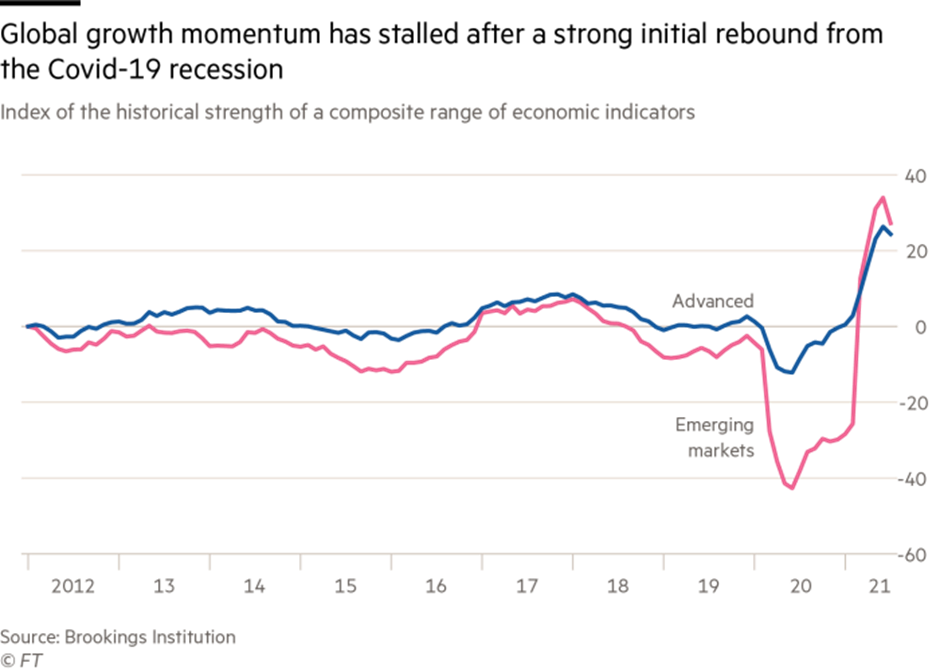

Also, there is the Brookings-FT Tracking Index for the Global Economic Recovery (Tiger) which compares indicators of real activity, financial markets and confidence with their historical averages, both for the global economy and individual countries, capturing the extent to which data in the current period is normal. The latest twice-yearly update shows a sharp snapback in growth since March across advanced and emerging economies.

On the other side of the stagflation scenario, inflation rates are rising everywhere. Back in December last year the US Fed’s median forecast for inflation in 2021 was 1.8%. In March that was nudged up to 2.4% and then in June up to 3.4%. It is now 4.2%. Over the same period their median forecast for 2022 has risen from 1.9% to 2.2%. The Bank of England’s and the ECB’s numbers have followed a similar path.

Global grocery bills are rocketing.

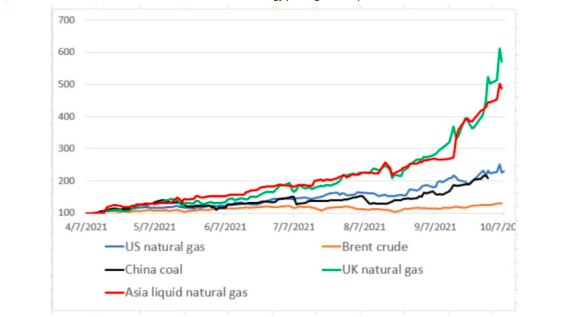

And energy prices have taken off.

What is causing this rise in inflation generally and in food and energy, in particular? The standard macroeconomics view is that there is ‘excess demand’. During COVID, consumers built up huge stashes of savings that they could not spend. But now that economies are opening up again, households are spending heavily at a time when global supply chains have been disrupted by the COVID pandemic.

This is the view of financial analysts, Jefferies: “the $2.5tn in excess household cash is an important buffer against stagflation, and we show that excess savings are distributed across the entire income distribution. To date, there has been very little evidence of demand destruction. Real spending is still close to cycle highs for most discretionary spending categories, despite significant price increases…A more rigorous analysis of price and volume changes by the San Francisco Fed shows that demand effects are the dominant driver of inflation at the moment, contributing 1.1% to y/y core PCE as of August. In contrast, supply-side effects contributed only 0.2%. This flies in the face of the prevailing narrative which attributes most of the price increases to supply chain disruptions. Yes, product shortages and supply bottlenecks are real, but they are largely a function of excess demand, rather than supply outages.”

So the Jefferies view is that this situation is just temporary or ‘transitional’, to use Fed Chair Powell’s expression. Once production, employment and investment get going and international supply chain blockages ease, then inflation pressure will also ease and things will get back to ‘normal’.

There are serious doubts about this rosy scenario. First on the demand side, is it really true that released pent up demand is the cause of rising prices? The idea that ‘excess cash’ will simply ‘sop up’ the extra costs of gas and food prices seems unlikely. After all, in the major economies this ‘excess cash’ is mostly in the pockets of the rich, who tend to save rather than spend. Higher prices are more likely to lead to reductions in spending in so-called ‘discretionary items’ as working-class households try to meet the rising costs of food and energy.

Moreover, accelerating inflation in essential goods and services is more likely to be the result of a ‘supply-side’ shock rather than excess demand. “We are not dealing with demand-push inflation. What we are really going through right now is a massive supply shock,” said Jean Boivin, a former Bank of Canada deputy governor now at the BlackRock Investment Institute. “The way to deal with this is not as straightforward as just dealing with inflation.”

On the supply side, there are those who argue that the 2020s are not like the 1970s with its stagflation, but more like the 1950s, when inflation incurred from the disruption and spending during the Korean war gave way to rising investment and profitability, so that industrial output and real GDP growth rates rose and inflation subsided. “With supply shortages set to persist for the next 6 to 12 months, the current period of “stagflation-lite” will persist a while longer. But it is likely to remain a pale imitation of the 1970s stagflation episode. Meanwhile, we do not share the pessimism of those who think that the current supply shortages are just one of a series of stagflationary shocks likely to hit the economy in the coming years.”

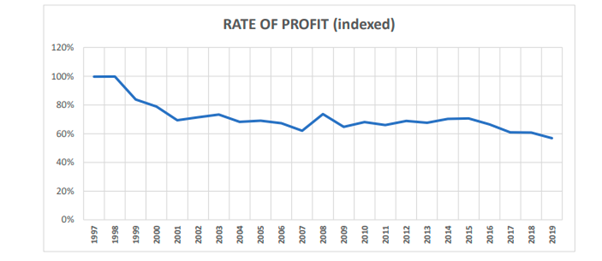

But are the 2020s going to be a new ‘golden age’ for capitalism like the 1950s with high profit rates and investment, real wage rises, full employment and low inflation? I doubt it; first, because the current supply-side ‘shock’ is really a continuation of the slowdown in industrial output, international trade, business investment and real GDP growth that was setting in in 2019 before the pandemic broke. That was happening because the profitability of capitalist investment in the major economies had dropped to near historic lows, and as readers of this blog know, it is profitability that ultimately drives investment and growth in capitalist economies.

In previous posts, I have provided the evidence of the decline in profitability in the US and elsewhere. Brian Green has a new analysis of UK business profitability which gets a similar result “before the UK entered the pandemic, the rate of profit had fallen sharply to stand 20% below the last mini peak in 2015.”

Again, you could even argue that the supply-side shock will remain not just because of low profitability and investment, but also because of the hugely increasing costs of dealing with climate change. This has led to sharp cutbacks in investment in fossil fuel energy exploration and production, putting many economies at risk of an energy supply crisis. This is the irony of market solutions to the global warming problem: driving up carbon emission prices and taxes merely causes a severe reduction in energy production because planning for the replacement of fossil fuel production with alternatives is non-existent.

If rising inflation is being driven by the weak supply-side rather than an excessively strong demand side, monetary policy won’t work. Monetary policy works by trying to raise or lower demand. If spending is growing too fast and generating inflation, higher interest rates supposedly dampen the willingness of companies and households to consume or invest by increasing the cost of borrowing. But even if this theory were correct, it does not apply when prices are rising because supply chains have broken, energy prices are increasing or there are labour shortages. As Andrew Bailey, governor of the Bank of England, has said: “Monetary policy will not increase the supply of semiconductor chips, it will not increase the amount of wind (no, really), and nor will it produce more HGV drivers.”

Indeed, as I have argued ad nauseum on this blog, pumping cash or credit into the financial system with ‘quantitative easing’ does not work to boost the economy if the ‘supply-side’ is not growing through lack of profitability. You can take a horse to water, but you cannot make it drink. That disconnection applies just as much when central banks tighten policy (ie withdraw credit and raise policy interest rates). Reducing demand will do little if supply is stagnant for other reasons.

Nevertheless, central banks are starting to tighten. Interest rates have already risen in Norway and in many emerging economies, while the US Federal Reserve and the Bank of England have made moves to tighten monetary policy. This won’t get inflation rates down, but merely increase the risk of a recession as debt servicing costs rise for companies already low on profits. That’s the dilemma for central banks and governments as they debate the issue of stagflation this week in Washington.

But let me finish this long post by reminding readers that mainstream economics has no coherent theory of inflation. As Charles Goodhart, a professor at the LSE and former member of the Bank of England’s monetary policy committee, remarked: “the world at the moment is in really a rather extraordinary state because we have no general theory of inflation”. The two main theories offered: the monetarist theory that money supply drives inflation; and the Keynesian theory that inflation is caused by tight labour markets driving up wage costs, have been debunked by the evidence.

So the mainstream has fallen back on a theory of inflation based on ‘expectations’. As Goodhart remarks, this is “a bootstrap theory of inflation”; that as long as inflation expectations remain anchored, inflation itself will remain anchored. But expectations depend on where inflation already is and so provide no predictive power. Indeed, a new paper by Jeremy Rudd at the Federal Reserve concludes; “Economists and economic policymakers believe that households’ and firms’ expectations of future inflation are a key determinant of actual inflation. A review of the relevant theoretical and empirical literature suggests that this belief rests on extremely shaky foundations, and a case is made that adhering to it uncritically could easily lead to serious policy errors.”

As regular readers of this blog may know, G Carchedi and I have been developing an alternative Marxian theory of inflation. The gist of our theory is that inflation in modern capitalist economies has a long-term tendency to fall because wages decline as a share of total value-added; and profits are squeezed by a rising organic composition of capital (ie more investment in machinery and technology relative to employees). But this tendency can be countered by the monetary authorities boosting the money supply so that money price of goods and services rise, even though there is a tendency for the growth in the value of goods and services to fall.

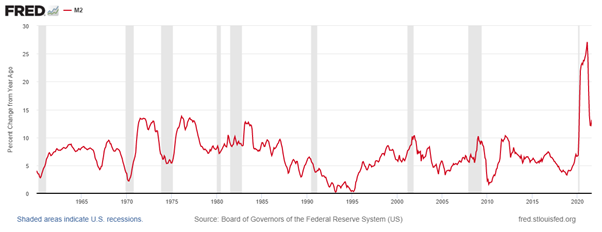

We have tested this theory during the COVID pandemic slump for US inflation. During the year of the COVID, corporate profitability and profits fell sharply. Wage bills also fell. As our theory predicted, the results were deflationary. But the Fed pumped in more money. US M2 money supply was up 40% in 2020. So US inflation, after dropping nearly to zero in the first half of 2020, moved back up to 1.5% by year end.

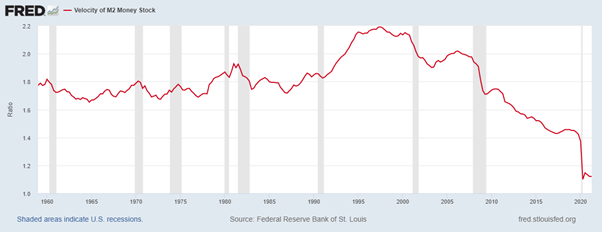

In slumps, the velocity of money, which is the pace of turnover of the existing money supply in an economy, falls. People and businesses make fewer transactions and instead tend to ‘hoard’ money. That was certainly the case in 2020, where the velocity fell to a 60-year low. Such a fall is hugely deflationary. But in 2021, the velocity of money stopped falling.

In 2021, all the factors that led to a near zero inflation rate in the US in mid-2020 began to reverse. At that time last year, we made a forecast that if profits and wages began to rise (wages, say by 5-10%; money supply by about 10%, then our model suggested that US inflation of goods and services would rise, perhaps to about 3.0-3.5% by end 2021. Actually, money supply has continued to rise faster than we forecast. And so US inflation is now over 4%, not 3.0-3.5% as we forecast.

Our theory of inflation suggests that the US economy over the next few years is more likely to suffer from stagflation ie 3%-plus inflation with less than 2% growth, than from either deflation or inflationary ‘overheating’ (4%-plus).

I appreciate your ‘general theory’ of inflation, but many economists are more interested at the moment in developing sectorally and geographically-specific accounts (e.g., weather, maintenance issues, high demand in Asia causing a spike in liquid natural gas prices and thus UK energy costs which isn’t much affecting the US for example). If we account for a few big ticket high-inflation items (energy being a huge one), where does this leave your ‘general’ model?

A quote from Richard Werner showing why the recent velocity decline is misleading.

[quote]

Solving the enigma of the ‘velocity decline’

The problems arising from the implicit assumption that nominal GDP (that

is, PY) can be used to represent total transaction values (PT) are obvious.

GDP transactions are a subset of all transactions. The mainstream quantity

equation (2) that uses income or GDP to represent transactions will thus

only be reliable in time periods when the value of non-GDP transactions,

such as asset transactions, remains constant (thus dropping out when con-

sidering flows). However, when their value rises, this will cause GDP to be

an unreliable proxy for the value of all transactions. In those time periods

we must expect the traditional quantity equation, MV = PY, to give the

appearance of a fall in the velocity V, as money is used for transactions other

than nominal GDP (PY). This explains why in many countries with asset

price booms economists puzzled over an apparent ‘velocity decline’, a

‘breakdown of the money demand function’ or a ‘mystery of missing

money’ — issues that severely hampered the monetarist approach to mone-

tarv nolicv implementation…

[end quote]

Recall the equation of exchange:

MV = PQ = GDP

V = GDP/M

Historically low interest rates have led to an increase in financial engineering. When money is borrowed for non-GDP transactions, then V falls as it must by arithmetical necessity. As such, velocity can not be looked at in isolation.

Stagflation 1: the end product of US military keynesianism’s brief, smilly-faced program to countervail the Great Depression, beginning in 1941 and ending in stagflation in 1973.

Stagflation 2: the end product of neoliberalism/neo-imperialistm’s militarized austerity/recolonization program to countervail military Keynesianism’s stagflation, beginning with Nixon’s trip to China and ending in our present state of stagflation…and, we can add, the depression (in small letters) that set in after 2008.

Biden’s seriously dead-pan militarist Keynsian gestures, coupled with the Republican’s farcical fascistic ones, eerily mirror politcal conditions in most of the independent Western “democracies” during the 1930’s (as they mirror now political conditions among most of the EU’s neo-imperial satrapies). The target of both the farcical military Keynesian Democrats and clownish Republican fascists is China, and for the same false reasons.

Can there be such a thing as history repeating itself farcically, but as tragedy? Your prediction of an indefinite period of global stagflation is tragedy enough, but hopefully right.

History doesn’t repeat itself… but I does rhyme!

“But are the 2020s going to be a new ‘golden age’ for capitalism like the 1950s with high profit rates and investment, real wage rises, full employment and low inflation?” -> Not at all, in the 20’s and 50’s the world was flooded with cheap oil, now?: “Global conventional crude oil production peaked in 2008 at 69.5 mb/d and has since fallen by around 2.5 mb/d.” Page 45 of the World Energy Outlook 2018 by the International Energy Agency. Download from https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/energy/world-energy-outlook-2018_weo-2018-en

Thank you for the citation. You have a penchant for having your finger on the pulse of discussions going on in the world of economics, which is the central strength of this website.

The elephant in the room is of course the fictitious capital bubble. If it bursts then within months we will have deflation. At the moment stock markets are holding their breath. And they are doing so for the reasons you outline in the article. They are caught in the twin beams of the car headlights, the one inflation the other decelerating production. Truly blinding.

My own estimation is that we will not have stagflation. Already the scamming of supply chains is reversing. JP Morgan has just told its clients to sell their shares in chip companies as inventory is beginning to pile up. DRAM prices have already fallen by over 20%. I think the 3rd quarter was one in which the rise in input prices began to overtake output prices as final sales started to decelerate. The 4th quarter will see an inevitable reversal in input prices and thus a receding in annual inflation. I suspect food prices maybe the exception.

As I have said repeatedly, +-92% of M2 is unspent revenue from previous periods of production. That is the ballast keeping prices upright and stable. The balance of 8% comprises credit money and state money generated by deficit spending. This was the case up to the pandemic and was partially true even for QE because much of that money tended to be trapped in speculation. Of course if the element of revenue falls as a percentage of M2 then stability can be lost and money as a standard of price will be compromised. But if we look at the latest CBO monthly bulletin which includes the US deficit for September, annualized the deficit has reverted back to $600 billion or the level found before the pandemic. So if my theory is right, which differs from yours because I have pointed out the double counting that goes into your equation, prices will straighten out during the course of this quarter.

Just a quick point about Ahmed Fares comment. GDP was constructed by two Russian emigres versed in Volume 2 of Das Kapital. It seeks to measure value produced (hence Domestic PRODUCT). It deliberately excludes capital gains which are not produced. The velocity of money is M2 divided by GDP. This is done to exclude factors outside production which Ahmed has pointed to. But the effect can be counter-intuitive. One could assume money exiting the real economy for the casino will lead to a slow down in velocity but the opposite effect would be case if as a result of this GDP contracts. If on the other hand money leaves the casino to be spent on main street then that could boost nominal GDP making it appear that the velocity of money has not risen. The strange world of capitalism.

Seems real wages are being cut by the fact that the money people get paid in is worth less (has a lower price in the market) even while the constricted supply of actual material goods and services is causing their prices to increase. I’ve heard that real wages have gone down 2% over the course of the pandemic.

“As regular readers of this blog may know, G Carchedi and I have been developing an alternative Marxian theory of inflation. The gist of our theory is that inflation in modern capitalist economies has a long-term tendency to fall because wages decline as a share of total value-added; and profits are squeezed by a rising organic composition of capital (ie more investment in machinery and technology relative to employees). But this tendency can be countered by the monetary authorities boosting money supply so that money price of goods and services rise, even though there is a tendency for the growth in the value of goods and services to fall.”

Pretty straightforward. Looks correct and definitive to me. I don’t see any logical flaw in it.

—

“This is the view of financial analysts, Jefferies: “the $2.5tn in excess household cash is an important buffer against stagflation, and we show that excess savings are distributed across the entire income distribution. To date, there has been very little evidence of demand destruction. Real spending is still close to cycle highs for most discretionary spending categories, despite significant price increases…A more rigorous analysis of price and volume changes by the San Francisco Fed shows that demand effects are the dominant driver of inflation at the moment, contributing 1.1% to y/y core PCE as of August. In contrast, supply-side effects contributed only 0.2%. This flies in the face of the prevailing narrative which attributes most of the price increases to supply chain disruptions. Yes, product shortages and supply bottlenecks are real, but they are largely a function of excess demand, rather than supply outages.””

This hypothesis doesn’t make sense, mainly for two reasons:

1) why would people all around the world and from all classes suddenly start to hoard money? Either way, that doesn’t explain inflation of essential goods, which cannot be suppressed from demand unless by force – people can’t just stop eating or drinking;

2) no matter how much one abuses the ceteris paribus fairy, the hypothesis still presupposes a natural exchange rate for the USD – which is a fiat currency. Why would one consider as a God-given right for the average American to always be able to purchase the same amount of goods, any time, anywhere? What if the USA is simply declining, the goods simply being redirected to somewhere else?

Sure there is a factor of “collapse of toyotism” and some space for modernization left (more people buying online, specially in the First World), but there’s a limit to this boon. It is very counter-intuitive to deduce the pandemic is actually good – and not bad – for capitalism, no matter how much Big Pharma profits from it.

“But this tendency can be countered by the monetary authorities boosting money supply so that money price of goods and services rise, even though there is a tendency for the growth in the value of goods and services to fall.”

So how is this different from the monetarist theory?

The counter-tendency does look very similar, though I’d have to think about it more.

The monetarists won’t have the tendency of the growth in the value of goods and services to fall, as that’s a Marxist economist claim.

Ross and Rech, matter matters in Marx’s method.

mandm,

Please explain.

For example, mmt is a function of, and occludes, the (social relation) matter at hand: neolberal capitalism’s re-colonization project (violently secured super-exploitation of ex-colonial living labor)–on which its austerity project at home depends: dolling out (otherwise worthless) paper/digital pittance wage goods dollars to permanently precarious, but relatively privilieged, living beings.

mandm,

OK. The “matter” is “social relations” and “social relations” was key for Marx.

I know it’s pointless raising the following in these quarters but I am going to anyway.

When I was doing my economics degree (almost 50 bloody tears ago!) I took a third year semester unit called “Comparative Economic Systems” – essentially the study of the various forms of the then contemporary socialist economies – there were a few around in those days – but not much if anything about Marxist theory per se.

In one tutorial, we digressed and talked some about Marx. When the tutor explained the pure state of communism it was apparent that what was required was a fundamental change in human nature for it to succeed. Even our very much left leaning tutor agreed. Changes in social relations just does not cut it. Marx had no idea. When I was 16 I was a communist (so I thought) but by the time I had my driving licence, after the reality of the history of socialism in the 20th century had begun to dawn on me, I had the good sense to jettison the lot.

The reason the socialist experiments of the 20th century failed, essentially was because human nature was what it is. The social relations had changed in these polities/economies but nothing else had.

In the real world, the lust for power and wealth is as potent in socialist systems as it is in capitalist systems. The common element in both these systems is the human being.

So as far as I am concerned, the “matter” is a bunch of bullshit. But I am interested in learning about Marxist economics, otherwise I wouldn’t waste my time here.

Please make allowance for my self indulgence.

Cheers.

Henry, I’m old too.Nevertheless, I get your point. You are no communist nor socialist nor Marxist.

Hi Michael, I’m a follower of your blogs and thought I might ask a question that is at a tangent to your more recent articles. Would you say if there is anything in the following observation? “The media seems awash with articles relating to supply side shocks, whether they be generated by domestic issues like Brexit and the pandemic or EU/global issues like energy/chip component/Air traffic. Now also with the hyping up of the anti China rhetoric; although this may be more related to Aukus and “security” sensitive trade like Huawei and 5G as the City of London is keen for business in the East. So there seems to be a coherence growing between trade issues and Johnson style populous appeal or at least a political shelter for this government but not without potential complications relating to greater reliance on regional hubs just as Britain exits the EU. Of course this might present problems for Starmer’s Blairism, even with a Blue Labour tinge and don’t mention Brexit. Not to mention the future value of the the £ when post pandemic spending and inflation picks up.” many thanks Stephen Harper

On Mon, 11 Oct 2021 at 15:38, Michael Roberts Blog wrote:

> michael roberts posted: ” The semi-annual meetings of the IMF and World > Bank start today where finance ministers and central bankers will meet in a > slimmed-down but in-person gatherings in Washington. This meeting is > likely to be overshadowed by the scandal involving the IMF chi” >

Hey, Michael! János Kornai just died. His Economics of Shortage was a very influential work and played a role in regime changes of socialist countries.

Think you could write a post about him?

Cheers