In my view, there are two great scientific discoveries made by Marx and Engels: the materialist conception of history and the law of value under capitalism; in particular, the existence of surplus value in capitalist accumulation. The materialist conception of history asserts that the material conditions of a society’s mode of production and the social classes that emerge in that mode of production ultimately determine a society’s relations and ideology. As Marx said in the preface to his 1859 book A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy: “The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness.”

That general view has been vindicated many times in studies of the economic and political history of human organisation. That is particularly the case in explaining the rise of capitalism to become the dominant mode of production. Now there is new study that adds yet more support for the materialist conception of history. Three scholars at Berkeley and Columbia Universities have published a paper, When Did Growth Begin? New Estimates of Productivity Growth in England from 1250 to 1870. https://eml.berkeley.edu/~jsteinsson/papers/malthus.pdf

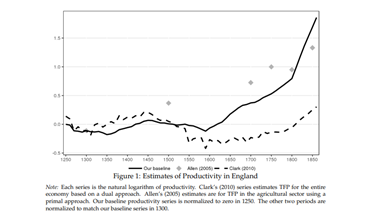

They attempt to measure when productivity growth (output per worker or worker hours) really took off in England, one of the first countries where the capitalist mode production became dominant. They find that there was hardly any growth in productivity before 1600. But productivity started to take off well before the so-called ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688 when England became a ‘constitutional monarchy’ and the political rule of the merchants and capitalist landowners was established. These scholars find that, from about 1600 to 1810, there was a modest rise of the productivity of the labour force in England of about 4% in each decade (so 0.4% a year), but after 1810 with the industrialisation of Britain, there was a rapid acceleration of productivity growth to about 18% every decade (or 1.8% a year). The move from agricultural capitalism of the 17th century to industrial capitalism transformed the productivity of labour.

The authors comment: “our evidence helps distinguish between theories of why growth began. In particular, our findings support the idea that broad-based economic change preceded the bourgeois institutional reforms of 17th century England and may have contributed to causing them.” In other words, it was the change in the mode of production and the social classes that came first; the political changes came later.

As the authors go on to say, “an important debate regarding the onset of growth is whether economic change drove political and institutional change as Marx famously argued or whether political and institutional change kick-started economic growth”. The authors don’t want to accept Marx’s conception outright and seek to argue that “reality is likely more complex than either polar view.” But they cannot escape their own results: that productivity growth began almost a century before the Glorious Revolution and well before the English Civil War. And “this supports the Marxist view that economic change contributed importantly to 17th century institutional change in England.”

The other interesting aspect of the paper is that the authors try to measure the impact of population growth on productivity and wages. In the early 19th century, Thomas Malthus argued that it was impossible for productivity growth to rise sufficiently to enable workers to increase their real incomes, because higher incomes would lead to increased births and eventually over-population, scarcity of food and famines etc, then reducing the population and incomes again.

The authors note that before 1600, there is evidence to support the Malthusian case. The period from 1300 to 1450 was a period of frequent plagues — the most famous being the Black Death of 1348. Over this period, the population of England fell by a factor of two resulting in a sharp drop in labour supply. Over this same period, real wages rose substantially. Then from 1450 to 1600, the population (and labour supply) recovered and real wages fell. In 1630, the English economy was back to almost exactly the same point it was at in 1300.

The reason that the Malthusian argument has validity before 1600 is that there was little or no productivity growth; so livelihoods were determined by labour supply and wages alone. Pre-capitalist England was a stagnant, stationary economy in terms of the productivity of labour. But so was the impact of the Malthusian over-population theory. The authors found that Malthusian population dynamics were very slow: a doubling of real incomes led to a 6 percentage point per decade (0.6% a year) increase in population growth. That implied that it took 150 years for a rise in real incomes to drive up population sufficiently to cause a reversal in income growth.

But once capitalism appears on the scene, the drive for profit by capitalist landowners and trading merchants encourages the use of new agricultural techniques and technology and the expansion of trade. Then productivity growth takes off at a rate increasingly fast enough to overcome the slow impact of Malthusian ‘overpopulation’. Indeed, with industrial capitalism after 1800, the growth in productivity is 28 times higher than the very slow negative impact of rising population on real incomes.

Thomas Malthus

This confirms the view of Engels when he wrote: “For us the matter is easy to explain. The productive power at mankind’s disposal is immeasurable. The productivity of the soil can be increased ad infinitum by the application of capital, labour and science.” Umrisse 1842

Before capitalism, feudal societies stumbled along with their economies ravaged by plagues and climate. For example, the Black Death of 1348 engulfed English society for more than a year, claiming about 25% of the population. For three centuries after the Black Death, the plague would reappear every few decades and wipe out a significant share of the population each time. So real wages in England were mainly affected by these population changes and the consequent size of the labour force (if, as argued above, at a very slow rate).

But under capitalism, productivity rose sharply and the level of real wages was no longer determined by the weather or pandemics but by the class struggle over the production and distribution of the value and surplus value created in capitalist production in agriculture and industry. One of the features of the rise of capitalism from 1600 that the authors point out is the increase in the working day and working year – another confirmation of Marx’s analysis of exploitation under capitalism.

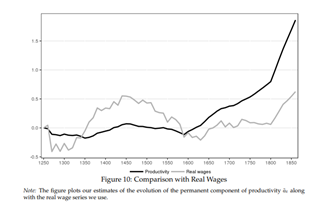

The authors note that as capitalism started to move from agricultural production to industry, in the latter half of the 18th century, real wages in England fell slightly despite substantial productivity growth. They cite one potential explanation, namely “Engel’s Pause,” i.e., the idea that the lion’s share of the gains from early industrialization went to capitalists as opposed to labourers.

The authors are reluctant to accept that Engels was right, preferring a Malthusian explanation in the late 18th century (having just rejected it). Moreover, they think real wages started to grow as early as 1810, before the period of the 1820-1840 cited by Engels as a ‘pause’. But anyway, we can see that the gap between productivity and real wages widened sharply from the beginning of industrial capitalism to now. Surplus value (the value of unpaid labour) rocketed through the early 19th century.

Most important, the study refutes the ‘Whig interpretation of history’, namely human ‘civilisation’ is one of gradual progress with changes coming from wiser ideas and political forms constructed by clever people. Instead, the evidence of productivity growth in England shows “sharp and sizable shifts in average growth” supporting the notion that “something changed.” i.e., that the transition from stagnation to growth was more than a steady process of very gradually increased growth.” On the gradual Whig interpretation, the authors conclude that “the results do not support this view of history.”

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334831075_The_Whig_interpretation_of_history

Also, the study shows that, as sustained productivity growth began in England substantially before the Glorious Revolution of 1688, it was not the change in political institutions that led to economic growth. On the contrary, it was the change in economic relations that led to productivity growth and then political change. “While the institutional changes associated with the Glorious Revolution may well have been important for growth, our results contradict the view that these events preceded the onset of growth in England.”

As Engels put it succinctly: “The materialist conception of history starts from the proposition that the production of the means to support human life and, next to production, the exchange of things produced, is the basis of all social structure; that in every society that has appeared in history, the manner in which wealth is distributed and society divided into classes or orders is dependent upon what is produced, how it is produced, and how the products are exchanged. From this point of view, the final causes of all social changes and political revolutions are to be sought, not in men’s brains, not in men’s better insights into eternal truth and justice, but in changes in the modes of production and exchange.”

The authors cannot avoid reaching a similar conclusion. As they say: “Marx stressed the transition from feudalism to capitalism. He argued that after the disappearance of serfdom in the 14th century, English peasants were expelled from their land through the enclosure movement. That spoliation inaugurated a new mode of production: one where workers did not own the means of production, and could only subsist on wage labour. This proletariat was ripe for exploitation by a new class of capitalist farmers and industrialists. In that process, political revolutions were a decisive step in securing the rise of the bourgeoisie. To triumph, capitalism needed to break the remaining shackles of feudalism…. Our findings lend some support to the Marxist view in that we estimate that the onset of growth preceded both the Glorious Revolution and the English Civil War (1642-1651). This timing of the onset of growth supports the view that economic change propelled history forward and drove political and ideological change.”

The development of capitalism in agriculture and in trade laid the basis for the introduction of industrial technology that led to the so-called industrial revolution and industrial capitalism. The Industrial Revolution occurred in Britain around 1800 because “innovation was uniquely profitable then and there”. As real wages rose, there was an incentive to exploit the raw materials necessary for labour saving technologies in textiles such as the spinning jenny, water frame, and mule, as well as coal burning technologies such as the steam engine and coke smelting furnace. Labour productivity exploded upwards. There was staggering rise in investment in means of production relative to labour. According to the authors, from 1600 to 1860, the capital stock in England grew by a factor of five, or 8% per decade.

Industrial capitalism had arrived, and along with rising productivity came increased exploitation of labour and the ideology of ‘political economy’ and bourgeois institutions of rule.

But how is this relevant today in terms of growth and the destruction of nature? “ The productivity of the soil can be increased ad infinitum by the application of capital, labour and science.”

Growth today means exhaustion of the soil and climate change, among other things. Yes, today capitalist productivity can feed all humans on Earth. However, in 60/70 years time, capitalist productivity will have to increase exponentially. That will again impact on nature and the environment.

To feed the growing population and preserve life on earth at the same time, capitalism has to make all the basic food we eat today synthetic. I don’t see how that could be done even under an alternative mode of production. Some anthropologists and socialists for a cooperative economy in harmony with nature. How that might provide for the world population is a big question.

Another alternative, which is already happening, is a decline in the global population. But that I think should be accelerated by more birth control.

Wage labour produces surplus value which is owned by capitalists. As output per hour of labour (output of surplus value) increases (productivity) so does capital. Engels was very young when he wrote that observation about soil. However, the point he was making is the same one Marx was making, that sensuous human activity produces wealth, not the abstract concepts of surplus value and capital. It’s a critique of Idealism as both Marx and Engels were surrounded by left Hegelians who were still falling into a mind/body dualist Idealism.

Do we as Marxists not need to be careful about going from one extreme (the wise political ideas of the English 17th century bourgeoisie drove economic growth) to the other opposite extreme (impersonal, inevitable improvements in economic productivity drove political change)?

Is there not a danger in interpreting Engels’s ‘succinct’ explanation of the materialist conception of history as privileging developments which are not influenced by human consciousness and action?

Is there not a dialectical process at work here, whereby people constantly and consciously strive to improve their lives through economic, political and cultural changes to their material, intellectual and spiritual environments?

It is true that the idealist ‘Whig interpretation of history’, which privileges the ruling classes’ role in human advancement, needs to be challenged and changed, but surely not at the expense of limiting the influence of human consciousness and action, which itself helps produce the economic growth which then helps produce the conditions for political change.

Mike yes we do need to be careful as both Marx and Engels pointed out at various times. It is a dialectical relationship between economic foundation and the ideas and action of humanity. I think this quote from Marx sums it up. “Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.”

Yes that’s right, Marx’s formulation of historical materialism is better than Engels’s ‘succinct’ one that you quote. This sentence in the quote…..”From this point of view, the final causes of all social changes and political revolutions are to be sought, not in men’s brains, not in men’s better insights into eternal truth and justice, but in changes in the modes of production and exchange.” – can all too easily be interpreted as locating causation outside of human imagination and action – the last thing we want!

The import of this quote is heavily influenced by where the emphasis is applied; try before or after the first comma.

But what an inheritance. Currently global renewable energy investment runs at $560 billion. So the 30 trillion cost of the pandemic pays for over 50 years of investment. The self inflicted war on terror running a bill approaching $10 trillion would have paid for the conversion of the US power system from black to green. The $1 trillion wasted on arms each year pays for all the desalination plants and their associated green power plants needed to end water shortage and begin reforestation. This is the kind of propaganda we need to make to promote socialism by showing how all this potential is being squandered and not only squandered but imperilling the planet, our home.

Agreed! And how not to fall into determinism and mechanical interpretation of the relation between the economic and the the ideological. After all, how to explain that a few capitalists, even a ruling class that is so integrated in the capitalist mode of production and the international circuit of finance capital yet it has both medieval and bourgeois thinking and morality?

Should be mentioned that even Engels was wary of such reductionism later on in his life, as seen in his letter to Bloch – I feel like he was slowly starting to see how the SPD was shaping up to be. Much to learn

https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1890/letters/90_09_21.htm

The problem here is documentation: we don’t have the peasants’ side of the story for the period. And we couldn’t, as they were illiterate.

The probably was a lot of consciousness and action before the 19th Century – we just don’t know about it (and never will, as the documentation isn’t available and will never be available).

The most we can do is to infer, .e.g the Gracchian land reforms that triggered the famous Roman Civil War; Spartacus’ slave revolt; some peasant revolts in medieval England, Italy, France, China and elsewhere. We do what we can, but we cannot fabricate narratives. You must understand that History is 99.999% forever lost – what survived to us is merely a tiny hole through time.

It doesn’t change the fact that all the evidence that survived to us points to the direction Marx’s theory is the correct one, though. History is not a hard science, but it still is a science, and we shouldn’t shy away from making scientific conclusions over the evidence.

Hello, Mr. Roberts! Long-time reader of your blog. Just chipping in that the embedding of the images from the article you’ve used appear to have been broken, as they’re much smaller, and therefore, harder to see. Cheers!

yes, the new wordpress format is ruining them i shall try and correct.

The power of the argument is irresistible. But would you agree that the shift in production away from tangible goods to intangible services constitutes a historic transformation in the mode of production? Tangible good production required centralised manufacturing, large-scale single-site employment and abundant fixed capital investment. Service creation (including health) works perfectly well when it’s decentralised and even when people work from home. And the amount of fixed capital investment can be modest (a laptop and relevant software). Your example of economic change occuring well before political change suggests that the revolution in the mode of production we’ve seen in our lifetimes will in due course be followed by political change but not now.

I’m working from home for the last year on a modest 11 years old desktop with an open source operating systen and some never paid for software. Right. But the “back office” I’m working with consists of two huge data centres with hundreds of servers and petabytes of storage and fiber cables running all around the country.

So services only serves the real economy.

But who or what is creating value? You or the data centre machinery? My answer is: you create the value sitting at home. The data centre supports your value-creation. This is completely different to the way value is created in tangible good manufacture where labour and constant capital (physical inputs and machinery) combine together in the same location.

“But would you agree that the shift in production away from tangible goods constitutes a historic transformation in the mode of production?”

This “historical transformation is the neoliberal one at the centers of the present imperial system. Industrial capitalism long ago used automation to degrade the worker into an adjunct of the machine, and the machine itself directed by technicians whose digitalizing labors are determined by capital’s law of value (not human need). But the machines themselves are quite tangible, as are the tangible wage goods you enjoy. So are the millions of alienated labor that produces them these tangible good at the peripheries of the intangible (except for weapons of war and order at center).

Most western economists (even good ones) persist in forgetting Marx’s image of a bloody birth of industrial capitalism: the blood of New World, Asian and African labor. India, for instance, was much richer than England in 1700, but its riches ended up in England, leaving Indian peasants and artisans with the famines produced by English machinery. The situation persists with the Modi comprador mode of production and the hundreds of million of peasants fighting for their lives.

correction of typo’s in the penultimate sentence of the penultimate paragaph: “So are the millions of alienated laborers who produce these itangible goods at the peripheries of the intangible (except for weapons of war and order) center.

This seems to suggest that tangible goods remain the sole value form in contemporary capitalism. Those of us creating services (intangible commodities) are therefore deemed not to create value. If that’s the case, then the 80+% of those employed in advanced economies who work in services cannot be exploited since definition they cannot be a source of value-added. The political implication is that workers in service industries have no direct interest in change: how can they when they create no value and consequently create no value.

Corrected version (this is what happens when you work from home).

“This seems to suggest that tangible goods remain the sole value form in contemporary capitalism. Those of us creating services (intangible commodities) are therefore deemed not to create value. If that’s the case, then the 80+% of those employed in advanced economies who work in services cannot be exploited since by definition they cannot be a source of value-added. The political implication is that workers in service industries have no direct interest in change: how can they when they create no value and consequently cannot be a source of surplus value.”

Eddie, i was suggessting that the “intangible” service economies at the center of present imperial system are supported by the tangible socially necessary goods produced by labor at the ex-colonial peripheries–not that servce workers produce no “value”. Any work–private prison guard, professional torturer or assassin employed by Eric Prince, Facebook ad-placement computer whiz, Google algorythmaniac, etc.–performed for some capitalist enterprise produces exchange value. Public librarians, teachers, postal workers, nurses, unpaid domestic (mainly women) workers are of no value, but use value.

Services (intangible commodities) definitely have exchange value (people create and others buy them. But do they have use value?

Marx writes in C1 Vol 1 Capital:

“The commodity is at first an exterior object, a thing, which by its properties satisfies human wants of one sort or another.”

The commodity has to be something that meets human “wants” (the word used by Marx is Beduerfnisse, which can be translated as “needs”, “essentials” etc).

Services do that.

The idea of the “exterior object” can be inferred as meaning the object must have material characteristics.

Another interpretation is that the object could also be something which is objectively perceptible at the level of the individual but lacks physical characteristics. This could include music and teaching, which are intangibles.

Marx’s ideas of wants can be more definitely interpreted as encompassing intangibles as the following sentence suggests.

“The nature of such wants, whether they arise, for instance, from the stomach of from imagination makes no difference.”

Here, Marx acknowledges that wants can be those emerging from the mind and not just those derived from physical needs such as hunger.

The logical conclusion is that use-value can be simultaneously objectively and subjectively perceptible.

The dichotomy is more clearly explored as the Chapter1 proceeds.

Marx wrote:

“Die Nuetzlichkeit eines Dings macht es zum Gebrauchswert.”

This is accurately translated as:

“The usefulness of a thing makes it a value in use (use-value).”

Marx then wrote this:

“Durch die Eigenschaften des Warenkoerpers bedingt, existiert sie nach ohne denselben.”

This sentence is conventionally translated as:

“Conditioned by the physical properties of the body of the commodity, it has no existence apart from the latter.”

But this seems to be wrong. A more accurate translation is: “Conditioned by the quality/nature of the body of the commodity, it does not exist without the same (the latter).”

This suggests Marx meant that what conditioned the commodity was something that could be intuitively perceptible.

The intangible characteristic of a use-value is further implied in the following sentence:

“A use-value or good only has value because labour is objectified or materialised in it.”

But how can labour be chemically or physically incorporated into a thing? There is no scientific explanation.

Logically, this sentence can only mean that use value has an intangible component and one that is only intuitively obvious, though it is objectively perceptible.

The logic of this statement suggests that the labour power embedded in a use value must be intangible.

Finally, the word “Nuetzlichkeit (usefulness)” implies intangibility because it begs the question: useful to whom?

For example, a flint sharpened so it can be used as a knife has no use value in today’s world (though people might keep it as a curiosity).

But the same object more than 10,000 years ago would have been deemed to be very useful.

It’s physically the same object but its use value has changed over time.

Use value therefore implies intangibility, a characteristic that can only be subjectively perceived.

Conclusion: intangibles created by capitalist enterprises have both exchange value and use value;

Services are commodities.

Workers who make them create value.

Service industry workers are exploited.

You obviously have read your Marx. Like a lot of people read Marx for the law rather than the spirit you miss the point: Capital is a critique of political economy, not an apology for the capitalist mode of production. His analysis of the commodity is just that: the analysis of the product of alienated human labor (labor power) whichi s produced for the sole purpose of profit for owner of the means of production. A commoditiy’s use value is incidental. From the capitalist point of view a loaf of bread during famine has no value if there is no effective demand for it. On the other hand, the service provided by a private police force protecting privately owned wheat silos add value to the grain inside. Capitalists usually have the means to wait out the human catastrophes they create.

Notwithstanding the obvious fact that in late capitalism many commodities are actually destructive of natural beings, including humans, your three final points in proof of the value of service work, tangible and intangible, are notionally correct.

But your home office job only makes sense in the wider context of a global industrial behemoth, larger than ever. White collar jobs are just a small and relatively unimportant tip of the entire iceberg.

What you describe is more akin to alienation of labor due to the immense specialization process on a global scale, where the First World countries keep the home office/services jobs (related to consumption) while the Third World countries keep the productive jobs (manufacturing and much of agriculture).

85% of those employed in the UK work in service industries. That’s 25+m people in the UK alone (not far short of the total who voted in the 2019 GE). At least 150m people work in service industries in the EU. The scale of service employment globally is enormous.

It’s suggested service workers cannot be the source of value.

But how can someone who doesn’t create value be exploited?

Why would a capitalist employ someone who doesn’t create value? e

But that is only possible because industrial workers are so productive. Service workers eat, dress, drive and live in similar homes to industrial workers.

My opinion is that as long as wage labour produces wealth for sale, be they goods or services, with a view to profit, the mode of production has not changed. The way Engels put it in 1877 is like this:

With the seizing of the means of production by society production of commodities is done away with, and, simultaneously, the mastery of the product over the producer. Anarchy in social production is replaced by systematic, definite organisation. The struggle for individual existence disappears. Then for the first time man, in a certain sense, is finally marked off from the rest of the animal kingdom, and emerges from mere animal conditions of existence into really human ones. The whole sphere of the conditions of life which environ man, and which have hitherto ruled man, now comes under the dominion and control of man who for the first time becomes the real, conscious lord of nature because he has now become master of his own social organisation. The laws of his own social action, hitherto standing face to face with man as laws of nature foreign to, and dominating him, will then be used with full understanding, and so mastered by him. Man’s own social organisation, hitherto confronting him as a necessity imposed by nature and history, now becomes the result of his own free action. The extraneous objective forces that have hitherto governed history pass under the control of man himself. Only from that time will man himself, with full consciousness, make his own history — only from that time will the social causes set in movement by him have, in the main and in a constantly growing measure, the results intended by him. It is the humanity’s leap from the kingdom of necessity to the kingdom of freedom.

To accomplish this act of universal emancipation is the historical mission of tt he modern proletariat. To thoroughly comprehend the historical conditions and thus the very nature of this act, to impart to the now oppressed class a full knowledge of the conditions and of the meaning of the momentous act it is called upon to accomplish, this is the task of the theoretical expression of the proletarian movement, scientific socialism.

full: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1877/anti-duhring/ch24.htm

However, I would add that we humans have learned a lot about our dependency structure with the environment since 1877, and we would have to consciously plan to live in harmony with ecosphere in order to avoid the sorts of catastrophes we now face under the rule of Capital with its prime directive of growth, growth of both variable capital and constant capital. But that can only be accomplished when the immense majority decide to abolish the social relation of Capital.

Reading Ellen Meiksins Wood currently (and recently re-read Perry Anderson.) With that influence, two things pop out.

First, the idea that capitalism is a marvel of production that breaks the Malthusian shackles with a shrug, revolutionizes daily life more or less daily, has created a whole new world of technology etc. seems to me to lead people to overlook the long, long transitional period. Capitalism, especially when it wasn’t overwhelmingly present but unevenly distributed in the late medieval social formation, simply was not the cornucopia. It isn’t just Objectivists I think who tend to think there was no capitalism rising before 1800 because, if it’s not rich, it’s not capitalism. (Sort of the same logic that leads them to think the USA or EU is capitalism but Haiti or Congo or Bolivia or Indonesia aren’t, so socialist performance in the socialist countries is only compared to the imperial metropoles.)

And this is political too. It seems to me that the absolutist ideology was a compromise between feudal survivals in land tenure. Perry Anderson emphasized the subordination of capitalism/nascent bourgeois society. But by the same token it marked an acceptance and attempted incorporation of the elements of capitalism. The tangled relationship between absolutism, early nationalism and mercantilism results in the easy pretense that the necessary ideology of capitalism is “democracy,” (despite the current counter-example of fascism and related political movements.) Or that “mercantilism” was not a part of capitalist development at all. Capitalism wasn’t wonderful to start with, the transitional epoch was agonizing. Standards for the transition from capitalism to socialism are of course much, much more stringent.

Second, a key aspect of economic change is the expropriation of church lands, aka, the Reformation. The slow growth of agricultural capitalism that laid the foundation for the takeoff (so to speak, not to sound too Rostow,) were laid decades before.

A fascinating post.

The relationship between “free will” and determinism, in regards to building socialism, is that we can only consciously make our collective futures by using a historical materialist understanding of necessity. This may sound like a burden to some, maybe. But it’s roughly like, to make technological advances you need to use the laws of physics and chemistry.

“The authors comment: “our evidence helps distinguish between theories of why growth began. In particular, our findings support the idea that broad-based economic change preceded the bourgeois institutional reforms of 17th century England and may have contributed to causing them.” In other words, it was the change in the mode of production and the social classes that came first; the political changes came later.”

That’s the problem diagnosed by Preobrazhensky in the 1920s in the USSR (“New Economy”): he stated that the greatest problem the Soviet Union had was that, contrary to the previous economic systems, socialism arose first through its political revolution, only to then work out on its economic revolution.

He then suggested the “socialist primitive accumulation” as the only way out for Soviet socialism. In one way or the other, that’s precisely what happened in the USSR during 1917-1945.

A later thought about the “Whig interpretation of history.” It is not clear who precisely the Whig interpreters of history are supposed to be. The primary opponent of the Whig interpretation of history was one Herbert Butterfield. Butterfield if I understand it correctly was a committed Christian. Whether that influenced him to imagine some perverse secular mental flaw of arrogance and ideology, i don’t know. But E.H. Carr pointed out in What Is History? that Butterfield neglected to actually name the members of the school or critique with details any of these Whiggish works. E.H. Carr is a pretty good bourgeois historian of the USSR, and therefore entirely out of fashion, where revivals of Conquest like Applebaum and Snyder are the current luminaries in the public sky.

“(Marx) argued that after the disappearance of serfdom in the 14th century, English peasants were expelled from their land through the enclosure movement. That spoliation inaugurated a new mode of production: one where workers did not own the means of production, and could only subsist on wage labour. This proletariat was ripe for exploitation by a new class of capitalist farmers and industrialists. .”

There is much truth in this analysis but to put the matter in perspective not only did enclosures continue into the late C19th, having reached their greatest intensity after 1750- the figures ion acreages enclosed are clear on that. But, and this is often forgotten, the nature of enclosing changed as the emphasis shifted from enclosing arable and pastures to enclosing common lands-wastes. At the same time successive changes to the law on poaching, gleaning, gathering fuel etc underlined the expropriations of enclosure.

And then there were successive changes in the Poor Laws undercutting the principle that labour had a claim on the harvest.

Malthus was simply jumping on an ideological bandwagon.

As to ‘wage growth’, the living standards of the rural population were based on a wide swathe of benefits of which wages were often a small part- such benefits included access to land and seed, use or ownership of livestock and a wide variety of other things including harvest feasts and bonuses and other customary considerations taken of right. It was while these benefits were being whittled away that the ideologists, including Parson Malthus, sang of the inevitability of poverty.

“The unstoppable end to the historical era of agrarian exploitation occurs when three conditions prevail.

One, the level of productiveness must develop to the point that a good number of working people are not needed in farming.

Two, some peasants must be able to keep more of their crops and other products than the subsistence minimum.

Three, social limits on inequality among the peasants must break down so that on one hand rich peasants appear and acquire more land than their family can work, and on the other hand some peasants become so short of land and even landless that they must hire themselves out at least part of the time.”

No Rich, No Poor, p. 46-7.

Of course, it is a bit more involved than this, as the rest of the chapter from which this quote comes discusses.

Michael and friends: anyone interested in productivity should have a look at this – the first fully modern metal lathe.

The 1751 Machine that Made Everything

nice video. except it abstracts from capital. it makes it external to the social relation and ascribes this to creativity of one guy

Hey there, Any chance you can speak on the state of the world economy? This Tuesday, March 30th at 7:15am EDT?

On WBAI in NYC.

I’m the host of the morning show.

Thank you,

Johanna Fernandez

__ Johanna Fernández, PhD Associate Professor Department of History Baruch College, CUNY Host, A New Day, 7-8am, M-Th WBAI 99.5 FM in NY, online @ WBAI.org Order Here.

Sent from my iPhone

>

Hi Johanna. I might be available but I have a zoominar around that time can you give me

Hi Johanna I might be available. I shall email you

Precisely because the social relation is not perceived consciously, people see the immediate form of appearance (wages, taxes, profits, and so on). Value and surplus value have to be investigated. So the role of consciousness is limited from the start. Too much emphasis on the role of conscious efforts needs to be tempered with its limitations. Otherwise, the failures of voluntarism and moralism in effecting change.

I have to wonder if Michael is familiar with the debates between Paul Sweezy and Maurice Dobbs, and then the one that came later between Robert Brenner and Immanuel Wallerstein. I only ask since this article is written as if they never took place. In fact, among historians–as opposed to econometrician–there is very little new research trying to vindicate Brenner’s diffusionist and Eurocentric mythology.

I have a dispute over the data produced in the Malthus study and the GDP in https://www.rug.nl/ggdc/historicaldevelopment/maddison/releases/maddison-database-2010 My opinion is that the two are incomparable while the other party says they are the same and this fictitious GDP is a good measure of productivity. I hope Michael can help out here.

Mr. Roberts, I do not agree that productivity is the reason salaries rose in the imperialist countries. It was more about creating an upper strata among workers via state policy in order to stop any insurgency at the home. Otherwise they would not receive more than their third world counterparts. This is also the reason why fascists want the refugees out but are quiet when it comes to the labor aristocracy who immigrates to their country legally:

https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1916/oct/x01.htm

I wonder your criticism of this.

I do not know what Michael Roberts would say but I can’t keep from interjecting…are “salaries” (wages, you mean?) higher in the capital cities of oppressed neocolonies? Everything I know says they most certainly are. I suggest that it is not necessarily the case that the workers are bribed by the superprofits of the metropolis exploiting the countryside.

Or, to be more precise, it is never the mass of the workers that are bribed but primarily the labor lieutenants of capital (a phrase coined by Daniel de Deleon.) The aristocracy of labor is not the mass of the workers but a select stratum. And moreover, as Lenin’s emphasis on the “bourgeois labor parties” says, those superprofits are devoted especially to cultivating a bourgeois labor movement integrated into bourgeois parties.

Formally speaking, the notion that capitalist superprofits means bribing the mass of people means there is a genuine objective unity of interests between capital and labor in rich countries. I think that neglects the probability that even poor people in a rich neighborhood will end up living better. But following this in a linear, moralizing way means concluding the most vicious exploiters of the people of the oppressed countries are the parasite on welfare. Even teachers, parasites on the public payrolls, do something.

Stepping back, there seems to be I think a neglect of the distinction between petty bourgeois and proletarian. Home ownership, which was indeed consciously promoted by the US government, was an effort to give families the hope that they might make capital gains from their home. By definition this would be non-proletarian income. (The disappointment of would-be petty bourgeois because of the social rot with its subsequent decline in property values is one source of petty bourgeois rage, i think, hence the rise of fascist tendencies like Trumpery.) But this implies we can quantify to a slight degree the magnitude of the “bribes” of the filthy masses of America by adding up things like the mortgage interest deduction, the subsidies from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. They are fairly sizable but I think they are not nearly so large as to prove that Americans as such are enemies of the people of other countries as such.

Their political commitments to anti-Communist crusades etc. are a different issue. But I would remind you that after WWII, tremendous effort was put into repressing the left in the US. And it was especially intent on purging the labor movement. Subversion by security forces and police, not the greed of the corrupt people, were drivers.

But why did the feudal mode of production change? I get why Marx thinks that the capitalist mode of production will change (falling rate of profit will produce its own grave diggers caused by the internal contradiction between labour producing all value and competition forcing capitalists to innovate using less and less labour). But what internal contradiction in its material mode of production caused the feudal mode of production to change? Why could it not go on and on and on? (The Black Death was an external event, not an internal contradiction.)

Good question – any views?

There is a serious problem with dialectics. Although Marx seemed to have put Hegelian dialectics “on its feet” it still is a too binary and teleological way of reasoning. IMO Marx didn’t use it much in Capital. Luhmann’s system theory (based on evolution) allows for multiple causes and developments. I think Marx analyses of capital fits within this theory.

Susceptibility to disease, starting with population density, continuing with transportation systems allowing the rapid spread of disease vectors, widespread malnutrition weakening immune systems, official indifference to sickness of the poor, a multitude of factors are very much “internal.” Yet they very much determine the effects of “external” factors like the Black Death. The inequality of the so-called Golden Age of the Good Emperors of the Roman Empire was terminated by the Antonine plagues. They were both internal and external too.

Further, although the Black Death was highly important in weakening serfdom in western Europe, it was equally important in *strengthening* serfdom in eastern Europe. The reason was “internal” factors, like the larger number of cities in the western parts and the greater number of transportation routes by sea and even river and the already greater development of mining and so forth. There were not so many Augsburgs in Poland and Russia so far as I know. The general image of the feudal mode of production being wholly backward doesn’t explain the Crusades, which are very much expansionist.

The Vikings established some of the most important medieval “states” such as in Sicily, Russia (Kievan Varangians,) Normandy–>England. Are Vikings internal or external factors?

The general notion of “external” factors gets always problematic with regard to war. Quite aside from military technology being as “internal” as all technology, the perceived need for an army plays an important role in the development of the state. Britain being an island had everything to do with the relative dispossession of armed forces from the landed nobility in England. (Ellen Meiksins Wood doesn’t seem to notice this but that seems to me to be an error on her part.)

Internal and external are not opposites, but presuppose each other in ways that can seemingly dissolve them into nothingness at certain times and places in the real world. Maybe that sounds like mysticism but I think it’s just dialectics.

Because the forces of production came into conflict with the relations of production.

Technological innovation allowed for the accumulation of labor in commodity-form. Capital is the self-expansion of accumulated labor. This expansion was thwarted by the superstructural institutions of the fuedal order – capital needs contracts to be enforced through a neutral (from capital’s perspective) arbiter – a giant legal apparatus ironed into the social fabric through a constitution. The commodity conquered Feudalism.

Excellent article,

1.-The discovery of Marx (and Engels), historical materialism. It is the economic structure of the mode of production that affects political, cultural and ideological structures and not the other way around. Marx applying a powerful spotlight to earlier secular ideological darkness. If even the non-socialist Branko Milanovic accepts it in this article – ‘’ globalinequality_ Marx for me (and hopefully for others too) ’’ it will be true.

A critic.

2.- Correlation is not causality. On the one hand, it seems clear from modern economic research that before the Glorious Revolution there were already changes in the economic structure of England. The reviewed work of the Berkeley and Columbia professors uncovers improvements in productivity and growth. And this other work ‘Structural Change and Economic Growth in the British Economy before the Industrial Revolution, 1500–1800’ by historians Patrick Wallis, Justin Colson and David Chilosi, work reviewed here www: //nadaesgratis.es/fran-beltran/ the-revolution-before-the-revolution, confirms these improvements in productivity and also discovers changes in the distribution by sectors of labor activity. And it is only the changes in the economic structure of the mode of production that are going to produce changes (reforms and revolutions) in the political structure, government and laws. But does any change in the mode of production modify the political structure? Are these exact changes in productivity, growth (growth of which no data is seen in this work, except for a sentence with 3 data) and labor distribution that cause the Glorious Revolution? The authors discover the temporal correlation but do not argue for causality. They only say ‘’ that broad-based economic change preceded the bourgeois institutional reforms of 17th century England and may have contributed to causing them ’’. ‘’ May have contributed to causing them ’’? Is that causality? No, of course, and therefore they only have a correlation. To correctly causalize, they should explain and prove why these concrete economic changes produce the concrete political changes that occurred in the Glorious Revolution. And they don’t. A simple criticism of this possibility is that if growth and income increases for the entire population, why would individuals and their social classes want to change anything in the Government and political laws? . The main political changes of this revolution (Parliament, Central Bank, expansion of joint-stock companies) were political changes that did bring growth to the social group. See graph ” British GDP per capita (in 1990 Geary-Khamis dollars), 1270-1870, with GDP increasing only after the reforms of the Glorious Revolution. Yes, it is true, everything begins with the economic structure, but for economic changes to affect the entire population, the Government and laws must be used without any escape. And what causes these political changes? In my point of view, the Glorious Revolution, like most of the relevant historical revolutions, has as its main cause another factor that changes in the economic structure: inequality. Extreme inequality (misery, etc …) is proven to be present in the situation prior to the Socialist Revolutions in the USSR and China, European Liberals of 1848, French R. and the increase in prices, unemployment and discontent is documented. general in the period prior to the 1st Civil War of 1642, a civil war that ended in the Glorious Revolution of 1688.

Apologies for the delay but actually I have been disturbed for days by this paper at least for the period of the 19th Century. The authors claim a productivity growth of 1.6% p.a. (or 18% per decade) from 1810. This has to be a serious underestimate. For example in Britain between 1815 and 1914 textile production grew by 1,500%, coal production by 2,000% and iron production by 3,000% against a population growth of 240% not adjusted for lifespan. On the other hand, because money was tied to gold there were frequent periods of deflation so that in 1784 for example, whereas 1 lb of cotton yarn cost a week’s wages, by 1832 it now only cost 3 hours labour. I use this metric because by the mid-19th century Britain produced half of the global output of textiles (not to mention half the global production of iron and two thirds the output of coal) .

So the question I am asking you is this, did the authors use physical or value metrics in calculating their productivity series (TFP). I was not able to discern this from their paper. If they used value of output, then we are looking at a serious underestimate of productivity growth which would not explain how Britain came to dominate global output by 1850. Looking forward to your reply.

Economic change predates political change – civil war and glorious revolution…a ‘break’ or discontinuous change (more like Consciousness and Identity thinking)

or

the institutional framework of feudalism can accomodate some economic liberalisation (privatisation) but once a certain point reached the framework has to change – dialectic of quantitative change becoming qualitative change – continuous change (more like history)

so

Enclosures sanctioned by feudal law

Enclosure of manorial common land was authorised by the Statute of Merton (1235) and the Statute of Westminster (1285)

Also textiles were not a product in the main of innovation and productivity gains but of Empire – the destruction of the Indian cotton industry of more than a million workers allowed lancashire mill owners and new world slavers to step in…