Australia has a general election on Saturday. The opposition Labor Party has been leading in the polls and given a redistribution of the seats in parliament that favours Labour, it is expected to gain office and defeat the incumbent coalition of the National and Liberal parties.

The usual thing said about Australia’s economy is that it is the ‘lucky country’. It was the only OECD economy to avoid a slump during the Great Recession and has enjoyed 28 consecutive years of real GDP growth.

But there have been quarters of downturn and when the sharp increase in population (mainly through immigration) is taken into account (up from 15m in 1980 to 25m now), per capital growth is not so stellar – about 1.7% a year compared to average annual real GDP growth of 3.1%.

Even so, Australians have experienced a much faster improvement in national output and real incomes than just about any other advanced capitalist economy in the last 30-40 years.

However, growth has been slowing significantly in the last few years, down to 2.3% yoy on the latest data. Indeed stripping out population growth, real GDP per capita has been no more than 1% a year since the start of the global Long Depression ten years ago.

Apart from immigration, Australia has been ‘lucky’ because of its close proximity to the fastest growing giant economy of China over the last 25 years. “Australia was uniquely placed to benefit from China and Asia’s long-term growth by exporting resources, agricultural produce and services to the region”. Also the economy benefited from an influx of skilled labour through immigration from all parts but also immigrants who came with wealth of their own to invest.” (Hockey)

The relative success of Australian capitalism has been expressed in the profitability of its capital. I collated three measures of Australia’s profitability as a capitalist economy since the early 1980s and profitability has risen by 40-60% – with only some signs of flattening out since the Great Recession.

But Australia is heavily dependent on its exports to China and world growth in general.

China is now the largest source of foreign investment in Australia, leapfrogging the US. Total investment in real estate was $74.6bn, up from $51.9bn a year earlier. And it’s mainly in real estate. This has led to a massive house price boom. Household debt has rocketed to 165% of personal disposable income.

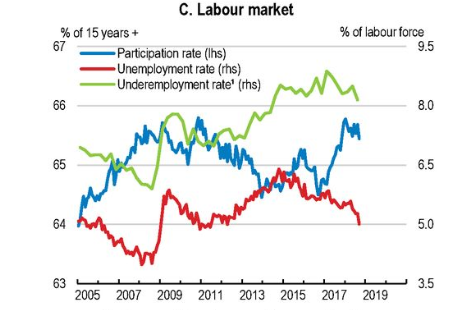

And although unemployment rates are relatively low, much of the new employment has been in temporary contracts and part-time. As a result, while the employment participation rate has been rising and the official unemployment rate has been falling during the housing boom, the ‘underemployment’ rate is near all-time highs.

Wage growth is also slowing.

You can get a job in Australia, but don’t expect it to be on a permanent contract or full-time. As a result, productivity growth has fallen from near 2.5% a year in the 1990s to under 1% a year now as capital investment is stagnating.

Australia may be a ‘lucky country’ but luck can change. The economy relies on raw material exports and so is vulnerable to any plunge in commodity prices and if China were to slow down or the trade war with the US really spike, then Australia is vulnerable. The OECD put it this way “a negative external shock cold prompt a sharp cut to incomes, a rise in unemployment and downturn in consumption. This would increase mortgage stress and further escalate a fall in house prices. A currency depreciation would also be likely.”

Ratings agency Moody’s has just forecast that Sydney house prices will drop by 9.3% this year, revised from its January prediction of 3.3%. It’s a similar story in Melbourne, with Moody’s original January forecast of a 6% decline updated most recently to an 11.4% fall this year. The Reserve Bank of Australia warned that more than 3% of Australian homes are in negative equity.

There is little to choose between the current government and the opposition on economic policy. Both are pledged to cut back on government spending, cut taxes and yet run tight fiscal budgets. It seems that government services and employees are the fall guys here.

And then there is climate change. Of all the major advanced capitalist economies, global warming is likely to damage Australia more than any other. Climate change in Australia has been a critical issue since the beginning of the 21st century. Australia is becoming hotter and will experience more extreme heat and longer fire seasons. In 2014, the Bureau of Meteorology released a report on the state of Australia’s climate that highlighted several key points, including the significant increase in Australia’s temperatures (particularly night-time temperatures) and the increasing frequency of bush fires, droughts and floods, which have all been linked to climate change.

Yet the economy depends very much on its fossil fuel exports and developing the mining industry. Non-renewable fossil fuels still account for about 85 percent of Australia‘s electricity generation. Australia is one of the world’s largest per capita emitters – producing some 1.3 percent of global carbon emissions in 2017 with only 0.3 of the world’s population.

While the centre-right government insists it is on track to meet Australia’s commitments under the 2020 Kyoto targets, it also seeks to placate the country’s powerful extractive industries and energy sector. A week prior to the election, incumbent prime minister Morrison announced $20.7m for a new school of mines and manufacturing at Central Queensland University.

Problems for Australian capital are hotting up in many ways.

It’s an off-topic, apologies, but, I think, it may be of interest to you. About the cycles in Capitalism I read your articles about and reached these conclusions: a) they are very good, deep and complete articles. You know what you are talking about and b) I think you should consider studying, if you have not already done so, the existence in capitalism and in previous modes of production, of one more cycle. A cycle of more power in its effects and longer duration. Name of the Cycle? Choose one: revolutionary struggle cycle, class struggle cycle, capital ownership cycle, production mode construction cycle, etc … Some authors who have studied it are Rosa Luxemburg, Enrst Mandel, Peter Sockt, etc. In the neo-Keynesian mainstrem economy this cycle is explained and coincides with the current impulse-propagation paradigm of Ragnar Frisk. I have debated, just a little, this cycle with current Marxist authors such as Rolando Astarita and Xavier Arrizabalo.

The last cycle was begun in 1917 and a synthesis of its argument is this: all economic models-modes of production generate, until today, inequality among economic agents. Why? Because capital (and its property) tend to be concentrated (Anwar Shaikh) into a single monopolistic agent because of its greater productivity and profitability generated by economies of scale. That economic inequality and that concentration of capital always generates the social collapse of the economic agents (individuals and companies) harmed. Harmed agents who are not able to integrate ” on time ” into monopoly. What are these harmed agents ?: small and medium-sized companies and salaried individuals, basically. The only historical, scientific and objective solution to this inequality (inequality that is extreme and that has no limit) is a shock, a disruptive event, … a socio-political revolution. An external shock, exogenous to the markets. A political shock Schok provoked and driven by losing agents in the concentration of capital. That revolution (1688-England, 1789 France, 1917 Russia and China, etc ..) is what level the previous extreme inequality (Walter Scheidel, The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century) How does the revolution achieve that leveling? It does so by expanding the owners of the productive capital, the capital of the means of production-companies. And so, the modes of production are an evolution from individual owners (Slavery, Feudalism) to productive capitals owned by many individuals (Capitalism) and, since 1.917 in Socialism, to social property (the property of all citizens).

Economic evidence in the last cycle: from 1.917, the upward phase of the cycle up to 1.980 generated: State GDP from 10% to 70% (Nordic Countries) // GDP annual growth to 5.5% in OECD (Golden Capitalism) and countries socialists // Almost full employment // Salaries on the rise // Education and quality public health // Demographic boom // etc .. In the phase of decline of the cycle, since the 1980s, productive capital returns to its previous owners. More than 600 public companies are privatized in Europe and now the Welfare State is privatized. Productive capital returns to the capitalist owners. The economy contracts and in all its economic variables the opposite happens to the bullish phase.

Labour has just lost the Australian elections. Shorten has resigned.

This just gives more evidence to my hypothesis, that is:

an imperialist country’s working class will always tend to, in times of crises and secular decline, to fascism instead of socialism.

This is just a logic deduction from Marx’s famous analysis, where he states humanity only abandons the existing social order when every possibilities of said order are exhausted.

In the case of the imperialist countries, we have that social-democracy/post-war boom incubated the germ of fascism in their respective working classes, because it gave them fond memories of capitalism. Therefore, their initial instinct in moments of decline will be to try to go back in time — to the “good times”.

Always? Well if the election in Australia proves that, what will the reelection of Modi “prove” about the working class in “non-imperialist” countries? Fascist because it “anticipates” “good times.”

“Logic(al) deduction” from Marx’s analysis? There’s no logic, nor a deduction in your argument. A post war boom created a “fond memory” of capitalism for the working class– that’s certainly subject to debate, since the fond memory is held by petit-bourgeois elements rather than workers. And “fond memories” have absolutely nothing to do with Marx’s material analysis that revolutions just don’t occur out of thin air, but occur when the relations of production have become a fetter on social labor, a social labor that is embodied in the means of production.

It’s official. Modi won with a “larger mandate” than before. Gives more evidence to my hypothesis that the bourgeoisie in “less developed” capitalisms will play the religious/national card as a path to “development” and petit-bourgeois “nationalist” elements will eagerly support such moves.

Just another logical deduction from the demands of capitalist accumulation.

“You can get a job in Australia, but don’t expect it to be on a permanent contract or full-time. As a result, productivity growth has fallen from near 2.5% a year in the 1990s to under 1% a year now as capital investment is stagnating.”

I don’t see how one follows from the other.

Employment of more people but on poor contracts with no training instead of investing in new labour-saving equipment that generates high productivity leads to low productivity growth. Of course, labour saving investment also threatens unemployment. Such is the contradiction.

Just a little factoid from someone ‘down under’.

The phrase “the lucky country” comes from a book by Donald Horne and is oft quoted on nationalist lines about how lucky we are to live in such a great country as Australia. But its almost the opposite of what he meant. The full quote is:

“Australia is a lucky country run mainly by second rate people who share its luck. It lives on other people’s ideas, and, although its ordinary people are adaptable, most of its leaders (in all fields) so lack curiosity about the events that surround them that they are often taken by surprise.”

“There is little to choose between the current government and the opposition on economic policy. Both are pledged to cut back on government spending, cut taxes and yet run tight fiscal budgets.” I don’t think that can be said of the policies of the Labor Party in this election. They risked a strongly redistributive that would have taken away many of the perks of the better-off middle class and raised taxes on those on high incomes to fund an expanded social welfare agenda. They also proposed to take climate change seriously and to curtail the worst of the gig economy. That made them a target for a negative scare campaign and outright lies that had all the hallmarks of the new right approach that delivered Trump, Brexit and the rise of Euro-fascism. The roots of Australian conservatism go back a long way but particularly since the conservative government from 1951 to 1972 which promoted home ownership as a point of civic self respect. This was abetted by the Hawke-Keating Labor government that opened up the Australian economy paving the way for the neo-liberal agenda that has persisted since. They also had to contend with a media landscape where the Murdoch press owns almost two-thirds of the press.

Peter interesting points. What do you make of this review of the election? https://www.jacobinmag.com/2019/05/australia-labor-party-bill-shorten-third-way

Thanks Robert. I agree with much of Daniel Lopez’s excellent article except that while we may be at the end of the neo-liberal period, we are also having to come to terms with new media technology which allows those with access to the enormous data now available to target crafted campaigns at the uninformed and fearful. During the election period it was hard to view a YouTube video without a right-wing ad aimed at undermining Labor’s message with outright lies. With much of the electorate disengaged and with fragmented members of our atomised workforce unable to organise through once powerful unions it is doubly hard to form the kind of army Daniel suggests is required. Also, with a disproportion of resources available to the right it also will be difficult (but not impossible) to fight a propaganda war on an equal footing. But of course, quitting is not an option.

Michael, sorry about the name blip. Writing late at night is not my forte.