Martin Wolf, the Keynesian economic journalist in an article in the UK’s Financial Times, has highlighted a paper by two economists at the US Federal Reserve, Joseph Gruber and Steven Kamin that showed a widening gap between corporate savings (or profits) and corporate investment in most of the major economies (Gruber corporate profits and saving).

This gap, technically called ‘net lending’ by corporations, Wolf describes as a global ‘savings glut’. The notion of a “savings glut” was first mooted by former Federal Reserve chief, Ben Bernanke, back in 2005. He argued that economies like China, Japan and the oil producers had built up big surpluses on their trade accounts and these ‘excess savings’ flooded into the US to buy US government bonds, so keeping interest rates low.

Martin Wolf and other Keynesians have liked this notion because it suggests that what is wrong with the world economy is that there is too much saving going on, causing a ‘lack of demand’. This is the proposition that Wolf recently pushed in his latest book.

In his book, Wolf concludes that the cause of the Great Recession “was a savings glut (or rather investment dearth); global imbalances; rising inequality and correspondingly weak growth of consumption; low real interest rates on safe assets; a search for yield; and fabrication of notionally safe, but relatively high-yielding, financial assets.”

And yet it was not falling consumption or rising savings that provoked the Great Recession, but falling investment (as even Wolf partially recognises in the quote). Investment is by far the most important part of the dynamics of a capitalist economy. As Wolf says: “companies generate a huge proportion of investment. In the six largest high-income economies (the US, Japan, Germany, France, the UK and Italy), corporations accounted for between half and just over two-thirds of gross investment in 2013 (the lowest share being in Italy and the highest in Japan).”

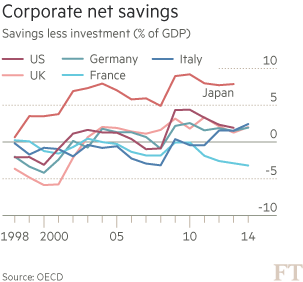

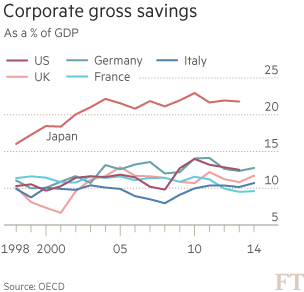

So is the gap between corporate savings and investment caused by a ‘glut of savings’? Well, look at the graph provided by Wolf, taken from the OECD.

With the exception of Japan, since 1998, corporate savings to GDP have been broadly flat. And for Japan, the ratio has been flat since 2004. So the gap between savings and investment cannot have been caused by rising savings. The second graph shows what has happened.

We can see that there has been a fall in the investment to GDP ratio in the major economies, with the exception of Japan, where it has been broadly flat.

So the conclusion is clear: there has NOT been a global corporate savings (or profits) ‘glut’ but a dearth of investment. There is not too much profit but too little investment. The capitalist sector has reduced its investment relative to GDP since the late 1990s and particularly after the end of the Great Recession. And when you read closely the Fed paper cited by Wolf, this is also the conclusion. Gruber and Kamin demonstrate that rates of corporate investment “had fallen below levels that would have been predicted by models estimated in earlier years”.

Joseph Gruber and Steven Kamin conclude their paper with a puzzle: “what is causing this paucity of investment opportunities, and what are its implications for future investment and growth?” Wolf cites various reasons for weak corporate investment: the ageing of societies thus slowing potential growth; globalisation motivating relocation of investment from the high-income countries; technological innovation reducing the need for capital; or management not being rewarded for investing but instead for maintaining the share price.

Many of these causes have been cited before and I have discussed them in previous posts. But most interestingly, after citing the Federal Reserve paper, Wolf fails to mention the conclusion of the Fed authors on the cause of weak investment in the last 15 years. I quote: “We interpret these results as suggesting that investment in the major advanced economies has indeed weakened relative to what standard determinants would suggest, but that this process started well in advance of the GFC itself. Finally, we find that the counterpart of declines in resources devoted to investment has been rises in payouts to investors in the form of dividends and equity buybacks (often to a greater extent than predicted by models estimated through earlier periods), and, to a lesser extent, heightened net accumulation of financial assets. The strength of investor payouts suggests that increased risk aversion and a precautionary demand for financial buffers has not been the primary reason firms have cut back investment. Rather, our results are consistent with views that, for any number of reasons, there has been a decline in what firms perceive to be the availability of profitable investment opportunities”.

So the cause of weak investment in productive assets and a switch to share buybacks and dividend payments and some cash hoarding was primarily due to a perceived lack of profitability in investing in productive assets. This confirms the conclusions reached by other studies that I have cited in previous posts dealing with the fallacious argument that corporates are ‘awash with cash’.

I would suggest that we already have an answer to the question of why ‘profitable investment opportunities’ are scarce. Overall profitability in the major capitalist economies peaked in the late 1990s and has not recovered to that level since. I have discussed this in a recent paper on the world rate of profit (Revisiting a world rate of profit June 2015). But here is a graph based on the work of Esteban Maito cited in that paper. Global profitability peaked in the later 1990s and has not recovered.

As a result, companies have used their ‘savings’ to invest not in productive assets like factories, equipment or new technology that could boost productivity growth (which has slowed to a trickle), but instead paid out more dividends to shareholders, boosted top executive pay and bought back shares to boost their prices. And much of this has been done by multinationals borrowing more at near zero rates, while shifting cash into offshore tax havens to avoid tax.

In my view, this clearly lends support to Marx’s law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall as an explanation of weak investment in the major capitalist economies since 1998. Marx’s law would suggest that any fall in the rate of profit should be accompanied by a rise in the organic composition of capital (the ratio of the value of capital equipment to the wages of the labour force) faster than any rise in the rate of surplus value (the profit extracted from the labour force). In my recent paper, I show that in the current ‘depression’ period since 2000, the organic composition of capital rose 41%, well ahead of the rise in the rate of surplus value at 7%. So the rate of profit has fallen 20%. ‘Profitable investment opportunities’ have shrunk.

We are told by the likes of Ben Bernanke and echoed by Martin Wolf that today’s problem of ‘secular stagnation’ is being caused by a ‘global savings glut’ in surplus countries and even in G7 countries. In other words, there was too much surplus (value) to ‘absorb’. But this is a fallacy. There was not a ‘savings glut’ but an ‘investment dearth’. As profitability fell, investment declined and growth had to be boosted by an expansion of fictitious capital (credit or debt) to drive consumption and unproductive financial and property speculation. The reason for the Great Recession and the subsequent weak recovery was not a lack of consumption (consumption as a share of GDP in the US has stayed up near 70%) but a collapse in investment.

Excellent entry Michael I’ll repost elsewhere.

Formulating the problem this way (weak demand vs. weak investment) seems metaphysical to me. Weak demand and weak investment are not two mutually exclusive outcomes. Moreover Marx’s analysis of realization shows that the circulation between constant capital and constant capital is definitely limited by personal consumption. And of course Marx doesn’t stop there. He also shows the true character of this “limitedness”, shows that, compared with means of production, articles of consumption play a minor role in the formation and development of the market etc. But what I mean is “lack of demand” (both in the articles of consumption and means of production) should not be underestimated and its existence should not be totally neglected just to attack Mr. Keynes.

I think his “sin” lies in his view that “flaws” of bourgeois society arise not from the nature of capitalism but from the psychology of individuals, that the inadequacy of consumer demand is caused by the inherent tendency which people have to save part of their income (and not by the impoverishment of the working people).

Memet, I’m not clear what point you’re making; I take Michael’s to be precisely that lack of *investment* demand is the proximate problem, but the reason for this is the low perceived profitability of possible investments

Julian, I did not understand your point either.

In the previous post I should have said “variable capital” instead of “constant capital”.

“In my view, this clearly lends support to Marx’s law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall as an explanation of weak investment in the major capitalist economies since 1998. Marx’s law would suggest that any fall in the rate of profit should be accompanied by a rise in the organic composition of capital (the ratio of the value of capital equipment to the wages of the labour force) faster than any rise in the rate of surplus value (the profit extracted from the labour force).”

But, that is not what Marx’s Law of The Tendency For The rate of Profit To Fall Says. What the law says is that the organic composition of capital rises because of rising social productivity, of labour, which results in a given quantity of labour processing much more material. It is not at all an increase in either the mass or value of fixed capital to variable capital that represents the rise in the organic composition of capital, but this rise in the mass and value of the circulating constant capital, the material processed to variable capital that lies behind it!

In fact, Marx makes clear that its not just the proportion of the value of output attributable to labour that falls in this process, but also the proportion attributable to fixed capital, precisely because the technological changes which bring it about mean that proportionately less fixed capital is required (one new machine replaces several older machines) and because that process results in the fixed capital having a lower value due to increased productivity in their own production.

So, in Chapter 6 of Volume III, Marx writes,

“In those branches of industry, therefore, which do consume raw materials, i. e., in which the subject of labour is itself a product of previous labour, the growing productivity of labour is expressed precisely in the proportion in which a larger quantity of raw material absorbs a definite quantity of labour, hence in the increasing amount of raw material converted in, say, one hour into products, or processed into commodities. The value of raw material, therefore, forms an ever-growing component of the value of the commodity-product in proportion to the development of the productivity of labour, not only because it passes wholly into this latter value, but also because in every aliquot part of the aggregate product the portion representing depreciation of machinery and the portion formed by the newly added labour — both continually decrease. Owing to this falling tendency, the other portion of the value representing raw material increases proportionally, unless this increase is counterbalanced by a proportionate decrease in the value of the raw material arising from the growing productivity of the labour employed in its own production.”

In which case, if there has been any falling rate of profit on the basis of this tendency, it would have to have been accompanied by rapidly rising levels of productivity, and much greater levels of capital accumulation in relation to the circulating constant capital. Given that there has been significant increases in the level of employment across the globe, alongside any such rise in productivity, that would also thereby have entailed not only a technological change in the fixed capital employed, but a significant increase in the mass of that fixed capital employed.

Given that your argument is that there has been no such increase in investment in fixed capital, its difficult to see how any lower rate of profit can be the result of the law of the tendency for it to do so, which requires precisely that relation to exist.

Instead, we would have to conclude that any falling profit margins is due not to the “Law”, but due to the same processes, Marx sets out in Chapter 6, of a profits squeeze, due to rising wages etc.

The point about capitalism is that you just can’t claim, “The problem is a lack of investment. ” The problem is just as much an abundance of investment.

No one can say that the problems bedeviling Rio Tinto, BHP Billiton, Caterpillar,– whole sectors like maritime shipping, ship building, steel. petroleum– are the results of a dearth of investment. On the contrary there’s a bit too much of that investment. Overproduction is always the overproduction of the machinery of production as capital.

And that’s where the fixed asset proportion is so pivotal, as Marx clearly notes — as fixed capital participates wholly in the labor process, but only incrementally in the valuation process.

Forgot to add– just look at the graph Michael provides– it’s not falling investment that creates the Great Recession; it’s the fact that investment rises in 2006, 2007, 2008.

We cannot simply point to the reduced rate of profit since the 1970s as the cause for conjuncture between cyclical and structural downturns– that would lead us to conclude that capitalism has been in some sort of “permanent crisis” since 1970.

Hey– if it’s been going on for 45 years, it’s not a crisis. It’s a business plan.

“permanent crisis” sums up capitalism pretty well

Really? So 1992-2000 is a “moment” of permanent crisis? And is the same as 2008-2015?

“We cannot simply point to the reduced rate of profit since the 1970s as the cause for conjuncture between cyclical and structural downturns – that would lead us to conclude that capitalism has been in some sort of ‘permanent crisis’ since 1970.”

No need to call it a permanent crisis; capitalism has been fundamentally different since around 1973. That’s when U.S. workers’ real median earnings peaked. That’s when significant reforms – on the order of Medicare, for example – were last obtained. Before then, big chunks of the working class won important improvements in wages, benefits, and social guarantees. Since then, workers’ class struggle has been almost entirely defensive, whether the profit cycle is currently up or down. Capitalism has entered a new historical phase.

Indeed, with the peak in the rate of profit in the US in 1970, capitalism certainly has been different, structurally. Still neither US capitalism, nor capitalism in general has been in a sustained crisis, as Marx described capitalist crisis, since then. Markets have not been permanently “frozen” illiquid or in decline. Industrial production has not been permanently crippled. The rate of profit did recover, although it did not exceed the 1969-70 measure.

Overall rates of growth, and overall rates of capital investment, have been lower post 1970 in the US, than in the period leading up to 1970. But that is not the same as claiming that the the period to date has been marked by a “permanent” dearth of investment.

It has been going on for 45 years, its one long depressionary wave. External factors are necessary to bring about a new major upturn, notice how they always talk about the post-war boom? Neither Iraq, Afghanistan, Yemen and so on have lead to a new Bretton Woods. Of course maybe it might be possible without a war creating a new hegemonic power, I think it would take the nationalization of finance in all the major countries though.

There is also the consequence that a rise in fixed capital, relative to labour, in terms of the actual realised mass and rate of profit, compared to the theoretically produced mass and rate of profit. Marx sets this out in Capital I and in Theories of Surplus Value I.

“If it be said that 100 millions of people would be required in England to spin with the old spinning-wheel the cotton that is now spun with mules by 500,000 people, this does not mean that the mules took the place of those millions who never existed. It means only this, that many millions of workpeople would be required to replace the spinning machinery. If, on the other hand, we say, that in England the power-loom threw 800,000 weavers on the streets, we do not refer to existing machinery, that would have to be replaced by a definite number of workpeople, but to a number of weavers in existence who were actually replaced or displaced by the looms.”

(Capital I, Chapter 15)

Marx goes on, there and in Theories of Surplus Value, to demonstrate that, in practice, the consequence of this rise in productivity leads to more not less labour being employed, and consequently a greater mass of surplus value being produced and realised than was previously the case. That is because, a higher rate of surplus value, means that more of it can be accumulated, and so more labour is employed. But, as indicated above, the introduction of new more productive fixed capital, which acts to reduce the value of output also means, that demand can rise, particularly for all of those commodities, whose price is currently too high to make their production profitable.

“This first period, during which machinery conquers its field of action, is of decisive importance owing to the extraordinary profits that it helps to produce. These profits not only form a source of accelerated accumulation, but also attract into the favoured sphere of production a large part of the additional social capital that is being constantly created, and is ever on the look-out for new investments. The special advantages of this first period of fast and furious activity are felt in every branch of production that machinery invades.”

(ibid)

Suppose to build a canal it would require 1 million workers, using picks, shovels and barrows. We might then have, assuming that the fixed capital and circulating capital turn over just once.

Fixed Capital £1 million

Variable Capital £1

Surplus Value £1 million.

The price for the canal would then be £3 million. The theoretical mass of surplus value, and rate of profit is £1 million, and 50%. But, it is only theoretical, because, if at this price no one will pay for the construction of the canal, the capital is never mobilised, and so the actual realised mass of surplus value is zero, and so is the rate of profit.

If instead a steam driven excavator is invented, with a price of say £0.5 million, this machine may replace 80% of the labour that would be required to manually dig the canal, and also replaces the majority of picks and shovels.

We would then have:

Fixed Capital £0.5 million

Variable Capital £0.2 million

Surplus Value £0.2 million.

The price of the canal is then £0.9 million, and at this price becomes a profitable proposition for capitalists who seek a cheaper form of transport to shift their commodities.

The theoretical mass of surplus value has fallen from £1 million to £0.2 million, and the theoretical rate of profit from 50% to 28.6%. But, the actual mass of profit before was zero, and is now £0.2 million, and the actual rate of profit on the canal was previously also zero, an is now 28.6%.

The organic composition theoretically to build the canal was originally 100%, or 50%, if as Marx says elsewhere, we calculate it against the total new value produced, i.e. s + v, rather than just v, so as to take into consideration any changes in the rate of surplus value, caused by the same rise in productivity. It is now, respectively 150%, and 125%. So, the organic composition of capital has definitely risen, and the theoretical mass and rate of profit has fallen, but the actual mass and rate of profit has risen.

Moreover, as Marx describes in the above referenced Chapter, and in Theories of Surplus Value, the consequence here is an actual increase in labour employed not just in this sphere, with a consequent rise in the mass of surplus value, and consequent effect on the rate of profit. The fact, that the canal now becomes a viable proposition, not only means that labour is used in its production and so creates surplus value, where previously none would have been produced, and workers would have remained unemployed, other workers are also employed producing the steam excavator, and auxiliary materials, other workers are employed constructing canal boats to use the canal, who would not have been employed and so on. As Marx sets out, in Capital I, this process led to large numbers of workers and capital being employed to produce railway stations, ports and so on.

I’ve set this out here, including a correction of some of the mistakes that Marx made in his explication.

“But, the actual mass of profit before was zero, and is now £0.2 million, and the actual rate of profit on the canal was previously also zero, an is now 28.6%.”

You can’t say this because we need to know where that capital was deployed previously. If the capital has been moved from one sphere to another we need to know the differences.

Many projects such as canal building are done by government agencies from revenue because such projects require so much capital and do not benefit any one individual capitalist. So a capitalist would be advancing capital to help his competitors as well as himself. A more real life example was called for.

“the consequence of this rise in productivity leads to more not less labour being employed, and consequently a greater mass of surplus value being produced and realised”

This has other dependencies and is contingent on other things so is a purely theoretical and abstracted statement. Readers should not take it as a statement of fact.

For example, realisation of profit is not simply down to labour employed.

Except the chart doesn’t show falling investment in the run up to 2008.

Gross corporate savings are flat or slightly rising, corporate investment is falling, and add to that stagnant wages and falling commodity prices. But somehow the rate of profit is in secular decline.

The chart shows, as other analytics show, an actual increase in investment in 2006, 2007 (and hanging over a bit into 2008).

The chart from Maito on a world rate of profit has the onset of crisis in 1963 and a postwar ‘golden age’ of 10 years at most.

Quite right Graham, and as this world rate of profit has been we are told, in this continual decline, punctuated by periodic rises, which do not take it up to previous highs, it makes you wonder how on Earth, all of the vast accumulations of capital over the 20th century, compared to the 19th century, let alone in more recent decades over previous decades has been possible!

The “Golden Age” of the 1960’s, must surely have been a much worse time to have been living than the even greater golden age of the 1930’s, or 1910’s, when the rate of profit was much higher, according to the theory.

“it makes you wonder how on Earth, all of the vast accumulations of capital over the 20th century, compared to the 19th century, let alone in more recent decades over previous decades has been possible!”

That’s an easy one to answer. First, it’s the law of the TENDENCY of the rate of profit to fall. Secondly, the fall produces offsetting actions. So capital accumulates in and by the actions of the bourgeoisie to offset the tendency of the rate of profit to fall–ALL those actions including attacks on the living standards of the workers, to layoffs, to improvements and increases in technology (leading to an increased tendency of the rate to fall), to asset liquidations and downsizing, to “offshoring” or runaway shops, to consolidations and mergers– to name just a few.

It’s not so much the graph as it is the categorizing of periods– 1964-1980 “crisis”? A sixteen year crisis? Resolved how in a period where the rate of profit is pretty consistently below the average for the crisis period itself? And then “depression” from 2000 on? 2003-2007 was a depression? Before millions of workers were sacked? When trade was expanding in both value and volume? When investments in the world maritime fleet would lead to a doubling of its tonnage? That’s a depression?

Well Graham looking at that chart the rop went down but not to the neo-liberal doldrums. So the 60’s was a Golden Age compared to our times.

But the chart says the postwar golden age or long boom ended in 1963. Periodisation is very important and I’ve never seen anyone claim that before. If the mid-60s were crisis times for capitalism, I don’t know where that leaves analysis.

I’ve seen it before. The Stalinist economists in the USSR and their supporters claimed that capitalism was in crisis after WWII, and went in to all sorts of acrobatics to show that living standards were actually falling in the West during the 1950’s, let alone 60’s, even though it was as obvious as the nose on your face that they were rising.

Its what comes from a dogmatic clinging to mantras such as the Law of The Tendency For The Rate of Profit To Fall, and the notion that capitalism is in catastrophic decline.

Looking at the paper “The downward trend in the rate of profit since XIX century”, we only need to wait another 50 years and capitalism will be dead.

Engels said that one of the greatest achievements of Marx was that he was the first economist to demonstrate that profit and the rate of profit is objectively determined. As he says, no previous economist was able to give a reason for the amount of profit being £10, rather than £20, or for the rate of profit being 10%, rather than 20%.

On the basis of any subjective approach, there is indeed no basis for determining those quantities. They become purely determined by subjective factors, such as the ability of workers to negotiate pay rises and so on, rather than, as Marx and Engels demonstrated, that ability to negotiate, itself being determined by the objective laws of value, which set the value of labour-power, and which underlie the demand and supply for labour-power.

The objective determination of the mass of profit, Marx sets out in Theories of Surplus Value, is the Value of commodities. That is the value of the commodities which comprise constant capital is objectively determined, and the value of the commodities that go into the production of labour-power, and so the value of labour-power itself, is objectively determined.

The value produced by labour is also likewise objectively determined, Marx demonstrates, because it is equal to the amount of labour performed by the collective labourer, during an also objectively determined normal working day. It is because all of these things are objectively determined that Engels was able to correctly state that Marx was the first to demonstrate that the mass and rate of profit is not some arbitrary and subjective quantum, but is itself objectively determined, because the mass of profit, is the difference between the objectively determined value created by labour, during the objectively determined normal working day, and the equally objectively determined value of the labour-power consumed in its production.

By the same token the rate of profit is objectively determined, because it is this objectively determined mass of profit, as a percentage of the objectively determined value of the advanced constant and variable capital.

But, there is also another objective feature of Marx’s analysis, which rejects subjectivism, in relation to the rate of profit and investment. In Capital III, Chapter 15, Marx answers those who argued that if there was insufficient demand for commodities at prices that did not reproduce the consumed capital, then they could simply consume the surplus value itself, in unproductive consumption. That would be to misunderstand entirely the basis of capitalism, Marx says, which is not to produce profits, for the sake of producing profits, so that the capitalist can then live better, but is to produce profits only in order to be able to accumulate in such a way as to defeat the competition, to gain market share, and so on.

The idea that, just because a capitalist cannot make some arbitrary amount or rate of profit, they will then not invest, or will invest less, is to completely negate the objective nature of Marx’s theory, and to make the determination of the accumulation of capital into a subjectivist theory, which relies upon the whims and preferences of the capitalist, and arbitrary decisions on what is an adequate or indequate rate of profit to encourage or discourage investment. It negates Marx’s argument that capital is FORCED to invest, whatever the rate of profit, whether it is rising or falling, by its very nature, and the nature of competition between capitals.

It is of course, quite possible that a lower rate of profit objectively makes a higher level of accumulation possible, because at one level the rate of profit sets the limit on such accumulation. But it only sets a limit, it does not determine mechanically what it will be, because a part of the total profit is also appropriated in the form of rent and interest, which are also determined by objective laws.

And as Marx sets out, if indeed the rate of profit is being squeezed because the accumulation of capital has reached such a level that the employment of labour has risen so much that wages have risen to such an extent that any additional employment of labour causes the rate of surplus value to fall, causing crises of overproduction, then its answer to such situations is not to stop investing, but to invest differently, to invest in labour saving technology, to overcome that problem, and thereby to reduce wages, and to cause a moral depreciation of existing capital stock, which of itself raises the rate of profit.

It is also not to suggest that even where the rate of profit is high, capital will not invest, or use the produced profits in other ways. As he states, it only requires that an even higher rate of return can be obtained from the use of those funds elsewhere. So, if a higher realised rate of profit can be obtained by investing in a foreign country, capital will tend to do so. The same thing applies to investment in some other line of production.

It can also be the case that if a higher rate of return, or what appears to be the same thing, as a large quick capital gain, can be obtained from speculation, then as Marx and Engels analysed as being the situation in 1847, capitalists may use their profits to speculate in Railway or other shares rather than productive investment.

What Marx’s theory cannot be compatible with is the idea that it is the rate of profit, which determines the rate of investment, other than in the sense above of setting a limit upon it, because that reduces his theory to subjectivism, to a subjective preference by capitalists of some arbitrary rate of profit below which they will not invest, rather than the objectively determined requirement to invest so as to compete. And as Marx says, even the limit set by the rate of profit to accumulation is elastic for modern capitalism, both because of the ability to use credit, and hoards of money-capital, and because of its ability to expand existing production, even within the bounds of the existing means of production.

“Owing to the immense elasticity of the reproduction process, which may always be pushed beyond any given bounds, it does not encounter any obstacle in production itself, or at best a very elastic one.” (p 304)

Boffy, can you provide a reference for the remarks you cite from Engels?

Julian,

Engels’ comments are in Capital Volume III, but I would have to spend time looking for the exact place that currently I can’t afford.

However, the actual analysis analysis by Marx that surplus value value/profit is an objectively determined quantum and Marx uses the words, that it is determined by the value of commodities, is contained both in his analysis in the final Chapters in Volume III, and in more detail in Part 1 of Theories of Surplus Value, where he analyses it in relation to the process of social reproduction, and the Tableau Economique.

He refers there in several places to it being the difference between the value of labour-power, and the value created by labour, and also refers to the rate of profit, in the same terms as the proportion of this profit to the value of the advanced constant and variable capital.

Just illustrating the consequences of the above for the rate of profit, and capacity for increased or reduced accumulation, and why Marx defines the rate of profit on the basis of the current reproduction cost of capital, and not on the historic money prices paid for it, he says the following, in examining the process of social reproduction, having stated that the constant capital itself must be replaced “in kind”.

“If the productiveness of labour remains the same, then this replacement in kind implies replacing the same value which the constant capital had in its old form. But should the productiveness of labour increase, so that the same material elements may be reproduced with less labour, then a smaller portion of the value of the product can completely replace the constant part in kind.” (p 849)

If we are considering this situation from the standpoint of the total social capital, and gross output, then,

“The excess may then be employed to form new additional capital or a larger portion of the product may be given the form of articles of consumption, or the surplus-labour may be reduced. On the other hand, should the productiveness of labour decrease, then a larger portion of the product must be used for the replacement of the former capital, and the surplus-product decreases.” (Capital III, Chapter 49, p 849)

A detailed refutation of the use of historic prices for analysing the rate of profit and social reproduction, is also given in Chapter 50, where Marx also sets out the point made above about the value of profit and rate of profit being objectively determined by the value of commodities, not their historic prices. He writes,

““The given number 100 always remains the same, whether it is divided into 50 + 50, or into 20 + 70 + 10, or into 40 + 30 + 30. The portion of the value of the product which is resolved into these revenues is determined, just like the constant portion of the value of capital, by the value of the commodities, i.e., by the quantity of labour incorporated in them in each case. Given first, then, is the quantity of value of commodities to be divided among wages, profit and rent; in other words, the absolute limit of the sum of the portions of value of these commodities. Secondly, as concerns the individual categories themselves, their average and regulating limits are likewise given. Wages form the basis in this limitation. They are regulated on the one hand by a natural law; their lower limit is determined by the physical minimum of means of subsistence required by the labourer for the conservation of his labour-power and for its reproduction; i.e., by a definite quantity of commodities. The value of these commodities is determined by the labour-time required for their reproduction; and thus by the portion of new labour added to the means of production, or by the portion of each working-day required by the labourer for the production and reproduction of an equivalent for the value of these necessary means of subsistence.” (p 858-9)

“The value of all other revenue thus has its limit. It is always equal to the value in which the total working-day (which coincides in the present case with the average working-day, since it comprises the total quantity of labour set in motion by the total social capital) is incorporated minus the portion of the working-day incorporated in wages. Its limit is therefore determined by the limit of the value in which the unpaid labour is expressed, that is, by the quantity of this unpaid labour.” (p 859)

The latter is determined by the maximum working day that the worker can perform and still be able to reproduce their labour-power.

“Since we are here concerned with the distribution of the value which represents the total labour newly added per year, the working-day may be regarded here as a constant magnitude, and is assumed as such, no matter how much or how little it may deviate from its physical maximum. The absolute limit of the portion of value which forms surplus-value, and which resolves itself into profit and ground-rent, is thus given. It is determined by the excess of the unpaid portion of the working-day over its paid portion, i.e., by the portion of the value of the total product in which this surplus-labour exists. If we call the surplus-value thus limited and calculated on the advanced total capital — the profit, as I have done, then this profit, so far as its absolute magnitude is concerned, is equal to the surplus-value and, therefore, its limits are just as much determined by law as the latter.” (p 859-60)

This point, that it is the value, and so the current reproduction cost, that is determinate, not the historic cost of capital, is again emphasised by Marx. And this also impacts the rate of profit.

“… the level of the rate of profit is likewise a magnitude held within certain specific limits determined by the value of commodities. It is the ratio of the total surplus-value to the total social capital advanced in production. If this capital = 500 (say millions) and the surplus-value = 100, then 20% constitutes the absolute limit of the rate of profit.” (p 860)

“What Marx’s theory cannot be compatible with is the idea that it is the rate of profit, which determines the rate of investment, other than in the sense above of setting a limit upon it”

But of course that’s exactly WHY Marx calls the law of the tendency of the rate of profit to decline the “most important law;” because it defines a limit to capital accumulation– where capital runs up the inside of a cage of its own making. Somehow Boffy manages to ignore this salient aspect of Marx’s critique.

I disagree with the argument that the “real problem” with capitalism, either in the short or long term, is a dearth of investment, but I don’t think Michael argues that there is a direct, linear correspondence between rates of profit and rates of investment.

Clearly, the rate of profit is a determinant of investment, in the sense that Marx takes the meaning of the term determinant over from Hegel– that is it is the organizing principle (in this case of capital investment) which in its fullest expression, becomes the negation– like, for example, wage-labor is the determination of capital. Some guy, German I think, said back in the day something like “All determinants are negations.”

I think MR does sail too close to the rate of profit being the singular, or at least overwhelmingly dominant, determinant of investment. It mirrors the reverse error of Keynesian.

Well it goes from 32 percent down to 27, but then in our times it goes as low as 17 percent or so. You’re right the periodization is iffy, yes the 60’s were definitely a golden age when the drop was more or less half of what we’ve seen since then.

So Maito is compared to the Stalinists of Post-WW2 by Boffy. This coming from the same guy who attacked anti-capitalism by saying ‘ISIS is anti-capitalist’. Well no ISIS is not anti-capitalist actually they’re raking in the dough atm and secondly here we have Boffy every time someone disagrees with him they become like a Stalinist or a Physiocrat or a Malthusian or heck ISIS! Facts are stubborn things Boffy and they have to be reckoned with whether you like it or not.

Hi Michael et al

here’s a comment I posted to the FT article discussed in Michael’s blog above…

The long-term decline in capital investment is hugely important, and it is clear from Martin Wolf’s comments and in the sources linked to in his article that mainstream economics has little idea why it is happening.

Two points.

First, the problem may be a good deal more severe than Mr Wolf’s article admits. Since changes to the UN System of National Accounts in 2008, corporate expenditure on R&D, software and also on branding and other forms of so-called “intangible capital” are now counted as investment rather than as expenditure on intermediate inputs. As Robin Harding reports (“Corporate Investment: A Mysterious Divergence,” Financial Times, July 24, 2013), tangible investments in plant and machinery by U.S. private industry have steadily declined from 14 percent of their output in 1980 to around 7 percent by 2011, whereas intangible investments have gone in the opposite direction and now make up more than two-thirds of total investments by U.S. industrial firms.

Second, Mr Wolf asks “Why is corporate investment structurally weak?” and mentions as one reason “Globalisation [which] motivates relocation of investment from the high-income countries.” This refers to the shift of production to low-wage countries, driven by global labour arbitrage, i.e. the substitution of relatively high-paid domestic labour with low-wage workers in China, Bangladesh etc. During the past three neoliberal decades, production outsourcing has become an increasingly-favoured alternative way to cut production costs and boost profits than investment in new technologies and expansion of production at home. The shift of manufacturing to low-wage countries is the most important underlying cause of the USA’s current account deficit which, as Martin Wolf explains in his book “Shifts and Shocks”, is the clearest expression of the “global imbalances” that were the proximate cause of the global financial crisis – yet this particular shift is not considered in his book and is glossed over in the article above. The US current account deficit declined from its high point of 5.8% of GDP in 2006 to 3.1% of GDP in 2013, but this largely reflects a big growth in its surplus on trade in services. The USA’s manufacturing trade deficit with developing economies, as a % of US GDP, actually increased over this period, from 2.4% of GDP in 2006 to 2.7% of GDP in 2013. In other words, some 85% of the USA’s current account deficit now represents the excess of manufactured imports from China and other low-wage countries over its manufactured exports to them.

Why have non-financial corporations favoured outsourcing over domestic capital investment? This is the most important question that needs to be asked, but neither Mr Wolf nor any other FT correspondent has dared to ask it. Yet the answer seems obvious: apart from being more profitable and much less risky, it frees up funds for capital concentration in the form of M&A and share buy-backs, and for speculative investments in financial markets, allowing companies from Boeing to Volkswagen to become more like financial corporations themselves.

The implications of this are profound. One is that profits, prosperity and social peace in western nations has become ever-more dependent on the extraction of value from super-exploited workers in low-wage countries. Perhaps the biggest of all is that the so-called financial crisis must be understood as the surface expression of a crisis whose roots are not in finance, but in capitalist production. No wonder that capitalism’s apologists don’t wish to go there.