So Greeks have voted NO by a significant majority in the referendum on the Troika conditions for bailout funds to repay Greek government debt. Given the scare tactics of the EU Commission and the German politicians, the might of Greek pro-capitalist media noise and the closure of the banks making it difficult, if not impossible, to conduct daily business, the majority ‘no vote’ is a huge defeat for the Troika and big capital in Europe; and a victory for the Greek people and European labour.

But, in a way, the result of the Greek referendum does not make any difference to dealing with the problems ahead. Tsipras and Varoufakis say that the vote will now enable them to negotiate a better deal with the Troika for a new bailout package that will, they hope, include some ‘debt relief’.

But that assumes the Troika will be prepared to negotiate at all with Syriza. Look at this comment from German economy minister Sigmar Gabriel (a social democrat!) who told the Tagesspiegel newspaper that this no vote makes it hard to imagine talks on a new bailout programme with Greece. And he accused Alexis Tsipras of having “torn down the last bridges” which could have led to a compromise: “With the rejection of the rules of the euro zone …negotiations about a programme worth billions are barely conceivable,….Tsipras and his government are leading the Greek people on a path of bitter abandonment and hopelessness.”

Even if they do, they may not offer any better conditions. Remember, Syriza had already agreed to raising social security contributions and VAT, to reducing pensions over time and to privatisations across the board (see my post https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2015/04/28/greece-crossing-the-red-lines/).

To quote Larry Elliot in the Guardian: “Greece’s membership of the euro hangs by a gossamer thread after the victory for the no side in the country’s referendum. The cash machines are running out of money and the economy is in freefall. The fate of the home of democracy is not in its own hands. If it chooses to do so, the European Central Bank could force Athens to default on its debts and issue its own currency on Monday morning by withdrawing emergency support for the Greek banking system.”

And “Whether they will do so remains to be seen. Indeed, the relentless mishandling of Greece ever since the crisis first flared up in 2010 suggests that blunder will follow blunder. It doesn’t help that relations between Greece and the other 18 members of the euro zone are now so sour. The chances of Greece leaving the euro by mistake, just as Lehman Brothers went bust by mistake in 2008, are reasonably high.”

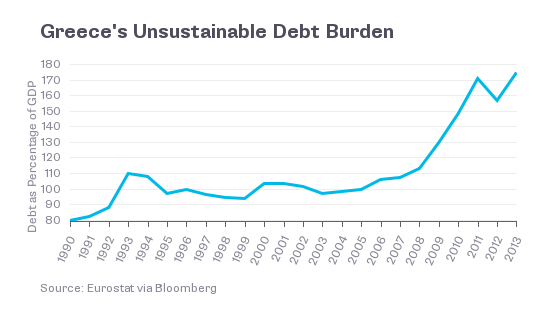

But longer term, the real issue is that Greece’s public and private debt burden is just too large for the Greek capitalist economy to service, despite already squeezing Greek labour to the death – literally. The Greek public debt burden arose for two main reasons. Greek capitalism was so weak in the 1990s and the profitability of productive investment was so low, that Greek capitalists needed the Greek state to subsidise them through low taxes and exemptions and handouts to favoured Greek oligarchs. In return, Greek politicians got all the perks and tips that made them wealthy too.

This weak and corrupt Greek economy then joined the euro and the gravy train of EU funding was made available and German and French came along to buy up Greek companies and allow the government to borrow and spend. The annual budget deficits and public debt rocketed under successive conservative and social democratic governments. These were financed by bond markets because German and French capital invested in Greek businesses and bought Greek government bonds that delivered a much better interest than their own. So Greek capitalism lived off the credit-fuelled boom of the 2000s that hid its real weaknesss.

But then came the global financial crash and the Great Recession. The Eurozone headed into slump and Eurozone banks and companies got into deep trouble. Suddenly a government with 120% of GDP debt and running a 15% of GDP annual deficit was no longer able to finance itself from the market and needed a ‘bailout’ from the rest of Europe.

But the bailout was not to help Greeks maintain the living standards and preserve public services during the slump. On the contrary, living standards and public services had to be cut to ensure that German and French banks got their bond money back and foreign investment in Greek industry was protected.

When it was suggested that German and French banks should take the hit, the ECB president at the time of the first bailout, Trichet responded that this would cause a banking meltdown as Lehman’s had done in the US in 2008. He “blew up,” according to one attendee. “Trichet said, ‘We are an economic and monetary union, and there must be no debt restructuring!’” this person recalled. “He was shouting.” By this, he meant no losses for the banks as ‘reckless creditors’, instead the Greeks must take the full burden as the ‘reckless borrowers’.

So through the bailout programmes, foreign capital was more or less repaid in full, with the debt burden shifted onto the books of the Greek government, the Euro institutions and the IMF – in other words, taxpayers. Greece was ultimately committed to meeting the costs of the reckless failure of Greek and Eurozone capital.

The Troika’s plan was to make the Greeks pay at the expense of a 25% fall in GDP, a 40% drop in real incomes and pensions and 27% unemployment rate. The government deficit was turned into a ‘primary surplus’ within the shortest period of time by any modern government. Greece has reduced its fiscal deficit from 15.6 percent of GDP in 2009 to 2.5 percent in 2014, a scale of deficit reduction not seen anywhere else in the world. Total public sector employment declined from 907,351 in 2009 to 651,717 in 2014, a decline of over 255,000. That is a drop of over 25%. Greece has gone from one of the lowest average retirement ages to one of the highest. In this sense, Greece had undertaken the most significant pension reform in Europe even before the latest demands of the Troika. This was austerity at its finest.

But the horrible irony is that this policy failed. Far from recovering, the Greek capitalist economy went into a deep depression. The supposed export-led economic recovery did not materialise. Instead the austerity measures have only made things worse.

So whatever the vote in the referendum, Greece cannot pay back the public sector debt, 75% of which is owed to the Troika of the Eurozone loan institution (EFSF) , the IMF and the ECB. And with the banks closed and credit withdrwan by the EB and the rest of European capital, the economy is in meltdown.

That the debt cannot be repaid is now openly admitted by the IMF in its latest debt sustainability report on Greece (here). The IMF now recognises that it got its forecasts of recovery hopelessly wrong.

Now, in its new report, the IMF reckons that the creditors must write off debt equivalent to at least 30% of Greek GDP to even begin to be able to sustain its debt servicing without default. As it puts it, “It is unlikely that Greece will be able to close its financing gaps from the markets on terms consistent with debt sustainability. The central issue is that public debt cannot migrate back onto the balance sheet of the private sector at rates consistent with debt sustainability, until debt-to-GDP is much lower with correspondingly lower risk premia”. Of course, any write-off must be on loans already made by the Euro Group. The IMF and ECB still expect to paid back in full!

Why cannot the debt on the Greek government books be serviced and repaid in full? It’s very simple. The Greek capitalist economy is just too weak, too inefficient and too unproductive to grow fast enough. Greek wages have been slashed, public sector spending has been cut savagely, pensions have been reduced sharply. Plans to improve tax collection and end avoidance and evasion are being put in place. But by IMF estimates, tax revenues will still not be enough to deliver a sufficiently large surplus before interest payments on existing debt for Greece to pay down its debt. Indeed, the IMF estimates are probably way too optimistic and the level of debt haircuts on the Euro institutions should be much higher than the IMF estimates.

So if the Syriza government or any other Greek combination government is forced into a new ‘bailout’ package in order to try and get the government to service its debt, the Alice in Wonderland scenario of more loans to pay for previous ones will continue – a true Ponzi scheme The more austerity and cuts in living standards are applied, the more difficult it will be for Greek capitalism to grow.

Whether there is now a deal with the Troika or alternatively, Grexit, the Greek economy needs to grow. Onlty this can make any public or private debt burden disappear. Take the US. The US public sector debt is huge at nearly 100% of GDP. But the US can service that debt easily because it has nominal GDP growth of just 4% a year. And the interest costs on its debt are very low at just 3% a year. As growth is higher than the interest cost on the debt, the US government can run a deficit of taxes versus spending (before interest) of 1% of GDP a year, and its debt ratio will still stay stable (but not fall).

Greece, on the other hand, in 2011, had interest costs of over 4% on its debt and nominal GDP of -5% a year, so it needed a government surplus of 9% of GDP just to keep the debt from rising. The government was applying austerity but still a deficit. Even the small debt restructuring of 2012 in the second bailout program did not stop the rise in the debt ratio. It is still rising.

In the 2012 bailout package, the Euro group agreed to put off repayment of its loans until 2022 and reduce the interest payments on them to just 2%. So, to stabilise the debt, the Greek economy now needs to grow by only 2% a year in nominal terms and balance its budget. But it cannot even do that yet. And even if it could, that would mean the debt ratio would just remain at 180% of a still contracting Greek GDP. So everything depends on restoring growth, much faster growth. That means more investment, new jobs, rising incomes and tax revenues and the ability to pay debt.

How can the Greek economy be made to grow? There are three possible economic policy solutions. There is the neoliberal solution currently being demanded and imposed by the Troika. This is to keep cutting back the public sector and its costs, to keep labour incomes down and to make pensioners and others pay more. This is aimed at raising the profitability of Greek capital and with extra foreign investment, restore the economy. At the same time, it is hoped that the Eurozone economy will start to grow strongly and so help Greece, as a rising tide raises all boats. So far, this policy solution has been a signal failure. Profitability has only improved marginally and Eurozone economic growth remains dismal.

The next solution is the Keynesian one. This means boosting public spending to increase demand, introducing a cancellation of part of the government debt and leaving the euro to introduce a new currency (drachma) that is devalued by as much as is necessary to make Greek industry competitive in world markets. This solution has been rejected by Troika, of course, although we now know that the IMF wants ‘debt relief’ at the expense of the Euro group (ie Eurozone taxpayers).

The trouble with this solution is that it assumes Greek capital can revive with a lower currency rate and that more public spending will increase ‘demand’ without further lowering profitability. But the profitability of capital is key to recovery under a capitalist economy. Moreover, while Greek exporters may benefit from a devalued currency, many Greek companies that earn money at home in drachma will still be faced with paying debts in euros. Many will be bankrupted. Already over 40% of Greek banks loans to industry are not being serviced. Rapidly rising inflation that will follow devaluation would only raise profitability precisely because it will eat into the real incomes of the majority as wages failed to match inflation. There would also be the loss of EU social funding and other subsidies if Greece is also ejected from the EU and its funding institutions.

Eventually, perhaps in five or ten years, if there is not another global slump, either the first or second solution can restore the profitability of Greek capital somewhat, on the back of a Eurozone economic recovery. But it will be mainly at the expense of Greek labour, its rights and living standards and a whole generation of Greeks will have lost their well-being (and their country as they go elsewhere in the world to make a living). Both these solutions mean that Greek labour will still be poorer on average in 2022 than it was in 2008.

The third option is a socialist one. This recognises that Greek capitalism cannot recover to restore living standards for the majority, whether inside the euro in a Troika programme or outside with its own currency and no Eurozone support. The socialist solution is to replace Greek capitalism with a planned economy where the Greek banks and major companies are publicly owned and controlled and the drive for profit is replaced with the drive for efficiency, investment and growth.

The Greek economy is small but it is not without an educated people and many skills and some resources beyond tourism. Using its human capital in a planned and innovative way, it can grow. But being small, it will need like all small economies, the help and cooperation of the rest of Europe.

The no vote at least tells the rest of European labour that the Greeks will resist the demands of European capital. That could encourage others in Europe to throw out governments in Spain, Italy and Portugal that continue to impose austerity at the dictate of the Troika. That, in turn, could bring to a head the future of the Eurozone as a Franco-German project for capital.

1. “Whether there is now a deal with the Troika or alternatively, Grexit, the Greek economy needs to grow. Onlty this can make any public or private debt burden disappear. ”

No, growth cannot and will not make the debt burden disappear. The “economy” does not exist as an abstraction. It exists as social relations of production; growth of capitalist relations of production will invariable increase the debt burden.

“Socialist growth” within one country will not ease the debt burden. Socialist growth that doesn’t aim at the revolutionary abolition of the debt a)isn’t socialist growth b) will collapse. See the history of the former Soviet Union.

There is a way to make the debt burden disappear– repudiate the debt in its entirety. Why are you so afraid to state that explicitly, Michael? Abolish the debt.

___________

2. “The third option is a socialist one. This recognises that Greek capitalism cannot recover to restore living standards for the majority, whether inside the euro in a Troika programme or outside with its own currency and no Eurozone support. The socialist solution is to replace Greek capitalism with a planned economy where the Greek banks and major companies are publicly owned and controlled and the drive for profit is replaced with the drive for efficiency, investment and growth.”

Nonsense. The so-called socialist option notes that Greek capitalism cannot restore living standards period. Not before, and maybe not even after a massive incineration of the components of capitalist production. The socialist option states that no matter what level of European capitalist support capitalism must attempt to drive the price of labor below its costs of reproduction.

As for “efficiency, investment, and growth…” exactly what do you think is going to be invested in your “socialist option”? What are we investing? You’re proposing “investing” as a way to avoid talking about the nasty bits of the road ahead, like a strategy to mobilize the development of organs of a dual power, which will take concrete actions towards seizing the means of production, expropriating the banks, liquidating the bourgeoisie, breaking up the military. Do you honestly think that there can be any “socialist investment” program that makes a bit of difference absent those prerequisites?

I like your characterisation of the three options, but isn’t option 2 a necessary precondition of option 3? You’re not stating it explicitly, perhaps because of the bad image of “socialism in one country”, but I don’t see how a socialist recovery (as well as a Keynesian one) can work without – in the short term – debt repudiation, monetary sovereignty and devaluation, capital and import controls and and a suspension or repudiation of the acquis communautaire… (this is of course what makes both options so difficult, because it exposes the country to immediate reprisals by foreign and domestic capitalists)

If I am not mistaken, Michael considers China a socialist state. I think this is what he has in mind when he talks about “socialist growth”, to somewhat emulate the Chinese management of economy.

Socialist growth? How about Dengs 4 reforms, the low-wage policy, and $1 trillion in FDI by capitalist countries?

Do not argue with me! I am just stating something I saw somewhere else!

“Do not argue with me! I am just stating something I saw somewhere else!”

Untwist your knickers. Those are questions. Where did you see it?

The whole text here is important, but I think this paragraph shows it a bit better:

“So there is nothing really in the aims and policy proposals agreed by the Chinese political elite that changes the nature of Chinese economic, social and political model. The majority in the leadership will continue with an economic model that is dominated by state corporations, but directed at all levels by the communist cadres. Markets will not rule and the law of value will not dominate prices, labour incomes or domestic trade. Of course, the law of value does operate in China, but mainly through foreign trade, capital flows (investment) and currency movements, but even here it is under strict limits, with only gradual moves to relax those limits.”

http://socialistnetwork.org/is-there-a-economic-bubble-in-china-about-to-burst/

Thanks for that.

Yeah, social ownership and democratic control over the collective product of labour while repudiating odious debt imposed by finance capitalists in other capitalist States would be the ultimate solution. Still, a socialist Greece would face massive pressure from the capitalist States and, in turn, the capitalist States would face massive pressure from their own wealth producers for more control and ownership over the collective product of their labour.

The question, as always, is what the level of class consciousness is and will be amongst the workers of the world as history is being made.

Will they fall for right-wing authoritarian calls for discipline and bondage enforced by a ‘great’ man on a white horse?

We shall see.

Neo liberal policies are no solution, even on the capitalists’ terms, as Michael Roberts points out. Despite that, this is what they are all pushing. They aren’t stupid, so what is their real goal? In my opinion, the goal is to use Greece to drive down the living standards – especially the “social wage” – of workers throughout the EU. In other words, more of the “race to the bottom”. The Wall St. Journal spelled this out very clearly in an article a few weeks ago, where they analyzed the (slight) economic recovery in Spain and also Portugal. Here’s a review of that article: http://oaklandsocialist.com/2015/06/03/spain-greece-and-the-race-to-the-bottom/

As a northern European in the Nordics (outside of the eurozone!) I suspect these comings days will be decisive. Samaras also had a deal he could not implement. He called new elections. Syriza seems to have incurred the wrath of most of the eurozone social democrats (been reading foreign newspapers one-line this morning). I champion for a socialist solution but am uncertain as to what the next steps will be.

I’ve not been able to shake the idea that Samaras and New Democracy brought down their government intentionally, knowing that the austerity they agreed to impose would be coming to a head this summer.

ND weren’t unhappy to be out of office. And Syriza is finished as any kind of new political force. They are more of the same.

Question: What are the options as far as the banking crisis? Obviously, one would be to repudiate the debt, leave the eurozone and start printing drachmas. Outside of that, what else is there (other than the Tsipras course of accepting what was unacceptable just a couple of days ago)?

Well, that’s a start– repudiating the debt. Let the EU worry about whether you’re in or out. But you have to seize the banks, immediately. And all “hard assets”– like ships, and private estates.

All of this, however, is impossible without a social class movement that is organizing itself outside the boundaries of parliament.

The banks should be seized in every country and converted into public utilities.

The other point is this: Michael Roberts is perfectly right that neither more austerity nor what amounts to a keynesian strategy can solve the problem and that the only other alternative is socialism. But the real question is what are the immediate next steps. In my opinion, these include building committees of struggle, maybe Committees of “No” to:

*Occupy the banks and take them over

*Occupy the Port of Pireus if necessary to stop privatization

*Link up with workers in any major work place that is under threat of closure to take them over under workers’ control and management.

In addition, given that there is a bit of a strike wave in Germany, wouldn’t it make sense to send delegations of workers to Germany to make direct links there to explain that they’re engaged in the same struggle? See: http://oaklandsocialist.com/2015/07/05/greece-votes-no/

I see that Varougakis has resigned. From his statement and from some analyses of his resignation, it seems that there is a danger that the “no” vote may be used simply to wring slightly less draconian measures from the “partners” instead of to institute a counter offensive.

“I see that Varougakis has resigned. From his statement and from some analyses of his resignation, it seems that there is a danger that the “no” vote may be used simply to wring slightly less draconian measures from the “partners” instead of to institute a counter offensive.”

That, “slightly less draconian measure” was what the referendum was all about from the getgo. Tsipras had basically agreed to the Troika’s final program, sending his agreement after leaving the negotiations and announcing the referendum and after the 2012 program had expired.

He campaigned for the “no” vote, claiming that the bigger the “no” vote, the better the deal he could get when negotiations resumed.

Varoufakis’ resignation is simply one of those pre-planned, cosmetic, and empty gestures, designed to show the Troika how “reasonable”,” and what a “good cop” Tsipras is by sacrificing the obnoxious “bad cop,” Varoufakis.

Reblogged this on Alejandro Valle Baeza.

The problem with Greece from a Marxian socialist perspective is that Greece generally lacks, with two partial and key exceptions, an indigenous proletariat, and of particular political importance here, a strong urban industrial manufacturing proletariat. The exceptions are mining and agriculture. (Quick ref to mining: http://www.un.org/esa/dsd/dsd_aofw_ni/ni_pdfs/NationalReports/greece/Greece-CSD18-19_Chapter_II-Mining.pdf)

The latter has a largely Roma agricultural proletariat, and the former, of unknown ethnic composition, is a traditional stronghold of the KKE (old and new), as I could see with my own eyes on a bus trip I took from Athens to almost the Albanian border, near the divide between the regions Epirus and (Greek) Macadonia, through the bauxite mining districts of Sterea Ellada, the roadsides covered with the graffiti of the KKE, and on through Thessaly, where one Roma “encampment” after another could be observed nestled in the farmlands – some the size of small towns. Otherwise the other important productive industry, shipping, undoubtedly employs mostly foreign workers.

Any program for “socialist development”, whether within “one country” or many, or within the capitalist world system or without, requires indigenous sources of production, and therefore an indigenous producer class, a proletariat, whether that production is for use or exchange. In Greece though, one important part is comprised of an oppressed ethnic minority held outside the political structure, and both are dispersed in the countryside in any case.

That tends to support my hunch that the social bases of Syriza lie in what Nicos Poulantzas (appropriately enough here) called the “new petite bourgeoisie” – with which he was theoretically obsessed with in Classes in Contemporary Capitalism – especially in the hard hit state sector, leading an alliance with another non-productive sector, service workers in the consumer sector (which outside tourism would also be hard hit). (Aside: Kinda like state workers under attack + $15/hr service worker movement in the U.S. now). If true, Syriza cannot possibly be headed in the direction of a short-term sustainable “socialst development”.

Instead, if the rumors I am seeing are true, Syriza could be going towards building a “national unity movement” with the traditional bourgeois parties on the basis of the resounding “OXI” vote. This latter does indicate that the “anti-austerity movement”, formerly restricted to the Left, has now assumed the dimensions of a genuine national revolt, a new development that we do need to now take into consideration. The Syriza concept might be a popular front hegemonized by Syriza as basically the (albeit non-productive) “worker” component. Its “Left” face would present itself as the working class hegemonic over the Greek bourgeoisie in a national popular front. But it would be a non-productive working class fraction exclusive of the above two productive sectors, because of the relation to the Roma, and to the KKE! And likewise the exclusion of their corresponding bourgeois/”old petite bourgeois” sectors, in agriculture the rural townie petite bourgeoisie, small farmers, and larger capitalist farmers Greek or foreign owned; in mining, one suspects multinational companies.

Perhaps this is the real significance of the Syriza logo, see http://www.syriza.gr/page/who-we-are.html#.VZv1DWNMLjY for a description. This claims the logo is an expression of the ideological unity of the labor (red), ecology (green) and “feminist and other new social movements” (purple) – I guess women get thrown into a residual category…but all I care about is that it include the Roma. Somehow I doubt it. What the gold star above represents is left unexplained. In any case though, it could just as well stand for a cross-class unity: “the working class (red), the middle classes (green), and the Greek bourgeoisie (the imperial purple :-)”, with the red flag in front symbolizing the “hegemony” of the working class. We shall see.

If so, the KKE would have for the moment stumbled into a “correct” position by sectarian means in not supporting such a popular front. But there is no way the dispersed and ethnically divided proletariat in Greece can come to power independently of the main urban centers (Athens, Thessaloniki), but no way the non-productive working classes in those centers could hold power for long without the inclusion of that proletariat. But that will be barred by the popular front.

That bus trip was the last week of this May.

I have just spent a week in the Greek Island of Crete (wonderful place) and couldn’t help noticing the small army of waiters, bar staff etc scurrying around attending to our every need.

Are these:

Productive working class

Non Productive Working class

Middle Class

Petite Bourgeois

????

I put these in the same category as retail trade in general. Whether the (generally low wage) workers in this sector are a kind of “transport worker” – as in the waiter has to transport the stuff to the table – or whether the cooks are a kind of artisan labor, or pre-industrial manufacturing labor, I am honestly agnostic on right now. I’m leaning not, because at best these are “marginally productive” (in a marginal theory of productive labor? This is what I am undecided on), but in any case 1) they are at the low end of the marginal scale, and 2) your consumption is non-productive (sorry 😉 so “qualitatively” these are non-productive.

BTW I did not mention the land-based non-passenger transport (air, truck, train) sector. Definitely productive, but in a small country like Greece, neither significant nor, perhaps, particularly Greek, as truckers may be foreigners.

“your consumption is non-productive”

If a capitalist employs 3 barbers to cut hair and they each cut 10 peoples hair a day but the capitalist pays them for, say, 7 cuts per day, is that productive? Even if when sitting in the barbers chair I am consuming unproductively?

Waiters like those you describe are producing a service which is sold by the owner of the business to gain a profit. They are productive working class in all senses, I believe.

The second and third options (the Keynesian and Marxist ones) are bound to fail. Greece is a small country that is highly integrated into the EU economy. It cannot survive on its own. Any attempt to stand up to capital will be met with a very swift reaction aimed at damaging the Greek economy in any way possible (and there’s quite a lot they can do). They will not allow the existence of a successful alternative that could strengthen parties like Podemos; rather, they’ll do everything they can to make Greece a failed state and convince voters across Europe that rejecting the euro will result in catastrophe. And it won’t be that difficult–the technical and logistical difficulties of switching to a new currency in a state of ‘normalcy,’ with ample foreign exchange reserves, would be daunting. Under the current circumstances, such a transition would lead to widespread chaos, with the prospect of economic recovery years away.

What now? Are bank occupations possible there?

http://oaklandsocialist.com/2015/07/08/greece-is-this-possible/

“2) your consumption is non-productive (sorry 😉 so “qualitatively” these are non-productive.”

Really? I disagree. I have to eat. I don’t own the means of/for my own subsistence. I exchange my labor time for money to purchase the means of subsistence. Sometimes I go to the grocery or the hypermarket. Sometimes, when conditions warrant, I go to a restaurant.

I spend my wages on food, returning “V” to the circuit of capital and in all ways– i.e. not just my wages in the circulation of commodities, but also my reproducing myself as a being with only labor time to exchange, as a carrier, a “mule” of surplus value.

I think that’s “productive consumption,” as opposed to the bourgeoisie spending their revenues on BMWs.

Service workers do yield a surplus value, just as transport and communication workers yield surplus value.

(P. Tapia & sartesian): The criterion of productive / non-productive is meant to be the traditional Marxist one, pertaining *only* to the capitalist mode of production, as opposed to “material production processes in general”. In another social world, the latter would certainly deserve to be regarded as productive; under capitalism it pertains only to labor power directly productive of *surplus value*.

Just because a capital realizes a profit, the money form of surplus value, doesn’t mean they directly produced the surplus value they realized as profit. Instead they have positioned themselves as an element only in the distribution of the surplus value, which is one of the functions of profit, and any wage labor employed in realizing that distribution is non-productive. Classic examples are the state, landlord property, speculative finance. As mentioned, I am “agnostic” on retail trade as this appears at the “end point” of the circulation of commodity capital, but the “final sale” transaction between the retail store and the consumer doesn’t appear as a circuit of commodity *capital*, just a simple commodity circuit. And there are plenty of sectoral examples of “mixed modes”: the transport sector, (passenger, non-productive, commodity capital freight, productive); the bulk warehousing operations of a Walmart or Amazon, so that even individual capitals are vertically “mixed mode”; the banking sector itself, for credit advanced to productive capital.

The reproduction of labor power itself, though certainly a process of material production, is not a *capitalist* production process – it is not directly governed by the law of value. It is indirectly influenced by it, of course, through the commodities consumed and the labor power exploited. But v(in) != v(out), not really, because the worker “owns and operates” the process of their own reproduction, not the capitalist (or else they would really be slaves!). This means this is purely a process of the transformation of use values, and not a “transmission” of exchange value via the laborers’ themselves. The commodities consumed by the worker are qualitatively different in both use and exchange value, reflected in that “variable” (or “constant”) capital has no objective existence in the *commodity capital* that remains at the end of production. The laborers’ own reproduction is not an integrated value component of the total value circuit of capital. This allowed Marx to put aside the worker’s own consumption/reproduction as a purely simplifying assumption in the analysis of capital. Consider it a “hot wire” or “short circuit” analysis.

Rather – in good news for the class struggle! – labor power reproduction marks a radical break in the circuitry, a real value non-identity between both endpoints of the reproduction of labor power process. It is a irreducibly *non-capitalist* process, for which the only solutions for the capitalist is to replace it with “dead labor” – machines – and sell use value garbage as commodities to the wage laborer (fast food, automobiles, “entertainment”, alcohol) in an effort to degrade the use value of their labor power. Both work together in relative surplus value production/extraction.

The issue was “productive consumption.” To the extent that such a thing exists then it has to exist as all other productive activities exist for capital– that is reproducing the relation that is capital. Value to expand value. I buy a car to get to my job on the railroad. Am I consuming productively? Of course I am. I consume commodities of food to reproduce my ability to provide labor power. Am I consuming productively? Of course.

As for retail– agnosticism is one thing, but it makes little sense to me to argue that railroad workers are “productive” in hauling container loads of televisions to the intermodal facilities, truck drivers are productive hauling the containers to warehouses; warehouse workers are productive stacking the TVs in the warehouses and distributing the TVs to the retail outlets, BUT retail workers are “not productive,” not generating a surplus value in “delivering” the ’embedded surplus value’ to the consumer.

And this: ” The laborers’ own reproduction is not an integrated value component of the total value circuit of capital.” is simply not accurate, IMO. Marx certainly does include the value of the reproduction of the labor power in the total value circuit of capital. Without that internal circuit, there is no surplus value to be expropriated. As a matter of fact, I think Marx’s discussions in Volume 2, and the incredible effort he takes with the schemas of reproduction between Dept 1 and Dept 2 are based precisely on this internal value circuit of the reproduction of labor power.

matt,

You have completely lost me I am afraid. i understand that for Marx productive labour is labour that produces surplus value, I also know that Marx said a actor could be productive labour if employed in a certain way. So why are waiters, bar staff and cooks who are employed by a capitalist concern NOT productive labourers? What does the consumption have to do with this?

When I buy a car or a mars bar am I consuming productively? Or are only capital goods productive? In which case how can a actor ever be productive?

Anyway I hope Michael has something to say about what I thought was the extraordinary intervention by the IMF (of all institutions!) into Janet Yellen’s Fed Funds policy: Hold off on any Sept. rate increase!

Are the bourgeoisie that nervous? Or did I imagine I saw it float by on my TV screen?

The US is using the IMF to pressure Germany, who wants the EZ to be their personal fiefdom. Capitalist bickering.

The IMF from 2008 on has been issuing advisories and cautions etc. I don’t think it’s that unusual. Tweedledum says don’t raise rates, while Tweedledee as represented by the BIS is warning about the long term damage to the EM countries and the commodity markets that extraordinarily low interest rates/”easy money” is having.

We have an answer to the “What Now?” question:

http://www.theguardian.com/business/2015/jul/09/greece-debt-crisis-athens-accepts-harsh-austerity-as-bailout-deal-nears

No means yes. Not exactly a huge surprise is it?

Re productive labour, very briefly. Labour power is a commodity. Its production is therefore part of the system. For a very long time bourgeois society let the workers themselves do most of the heavy lifting involved in raising new generations of labour power – and part of a worker’s wages went to reproducing and raising new labour power.

Nowadays the raising of new labour power is being brought into the system explicitly. The demand for a literate labour force prompted the bourgeois state to start universal schooling, but this was mainly state or ngo (obscurantist ie religious) funded. With the drive to privatize everything and generate surplus value directly in every sphere of the economy (even prisons and the military god help us), state involvement in reproduction is becoming private. This also goes for the sectors involved in maintaining the value of labour power over time as well as raising it – ie health care and social security.

So it’s ludicrous to automatically exclude any labour power that isn’t involved in industry or the transport of goods from the productive category.

Agricultural labour power is also productive if it’s exploited to create surplus value, goes without saying, but we’ll ignore it and count agriculture as just another branch of industry to keep things brief.

The character of consumption has nothing to do with this question at all. In Theories of Surplus Value Marx makes it clear that whores and opera singers and hack writers are all productive if they’re employed by a capitalist and paid wages ie generate surplus value. The end consumers throw money into the circuit of capital, and nobody gives a toss where they get it from, or how productive their consumption of the trick or the aria or the chick lit might be.

Rather than comment on the nature of both productive & unproductive labour, for information here’s the 4-page statement from the euro finance ministers’ meeting today, Sunday, 12 July, 3pm Brussels time:

(Sky journo)

In a tweet re-posted by the Guardian today at 6.56pm there’s an important error. A Dublin economics prof, Karl Whelan, says, “No haircuts inside euro but a ‘possible restructuring’ if Grexit is a huge sweetener designed to boost support for Grexit in Greece”. But the statement says explicitly that altering repayment terms may occur independent of Greece being in “the euro area” – as I’ll now show.

Debt restructuring appears on the final page of the statement. It’s in square brackets (assumed by observers as lacking unanimity), & says it could occur “in the context of a possible future ESM programme, and in line with the spirit of the Eurogroup statement of November 2012”. This could be “longer grace and repayment periods” – but no reduction of the principal: “The Eurogroup stresses that [nominal] haircuts on the debt cannot be undertaken” (original sq. brackets).

‘Temporary Grexit’ – the statement uses a term from popular US sports – appears only once, and it’s the topic of the one-sentence final paragraph: “[In case no agreement could be reached, Greece should be offered swift negotiations on a time-out from the euro area, with possible debt restructuring.]”

Whelan has inexplicably missed the other scenario for debt restructuring.

Not that anyone is reading this post (it’s wrapping yesterday’s virtual fish-n-chips?), but for completeness this is the official text of today’s agreement, Monday, 13 July:

http://t.co/dfwTY1uCxr (PDF)

Its achievement has been variously described as this:

“Der Katalog der Grausamkeiten” (the list of cruelties, atrocities)

“Germany refuses to accept Greece’s surrender”

“merkel/holland session with tsipras said to resemble ‘extensive mental waterboarding’ – top official”

“’They crucified Tsipras in there,’ a senior eurozone official who had attended the summit remarked. ‘Crucified.’”

“Two officials who observed Tsipras independently described him as a ‘beaten dog'”

(Der Spiegel front cover; Paul Harris tweet; Ian Traynor tweet, Guardian; FT; Bloomberg).

Drakon laid down the law in Athens. Merkelon laid down the law in Athens.

Just like Chile 1973 the limits of a certain kind of politics has been demonstrated for the world to see. But will anything be learnt?

Snippets of the updated IMF Debt Sustainability Analysis of Greece was leaked by journos today (Tu14Jul), but not the document itself. Reuters, who broke it, say, “[a]n EU source said the new debt sustainability figures were given to euro zone finance ministers on Saturday” – so they knew about it during the ‘negotiations’.

Peter Spiegel (FT) says what’s most salient is the tone of the document: “sends signal they want out of Greece completely” (tweet, teatime, today).

Guardian said, “the Fund cannot lend to a country if it doesn’t believe it would be sustainable. So unless Europe swallows the reality that Greece needs major debt relief, the IMF won’t provide any more bailout funds.”

No-one gave the rules but this is suggestive: table 7, “Debt Burden Benchmarks”, page 32, of the IMF staff guidance document of 9 May 2013:

http://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2013/050913.pdf

Greece is categorised as a “emerging market”, not an “advanced economy”, so its state is judged solvent if its debt is no more than 70% of its GDP, & liquid if its gross financing needs is no more than 15% of its GDP (cf. 85% & 20% for the “advanced” ones amongst us). Can’t find the rule about when lending is permissible, but unless the values were radically different in 2010 (which they wouldn’t have been), the IMF shouldn’t have lent money to Greece in the 2010 (when public debt was c. 150%) & 2012 bail-outs – nor the third one which has turned Tsipras into a “beaten dog”.

So corresponding to the ECB violating its duties by an act of omission, here we have the IMF violating its duties by acts of commission. It must be nice being in a strong enough position to break the rules whenever you want.

Jara Handala writes perceptively but a bit enigmatically: “Just like Chile 1973 the limits of a certain kind of politics has been demonstrated for the world to see. But will anything be learnt?”

The thing is to be specific about the kind of politics – popular front left opportunism à la Allende and Tsipras – and the reasons for its failure. It failed because these leaderships refused to mobilize the working class and its allies for the inevitable bloody confrontation with the class interests they were threatening. So they were left high and dry as isolated targets when the tanks rolled in. Literally in Chile, with Allende committing real suicide in his last stand, as he was blown to pieces by Nixon-Pinochet air power, and metaphorically in Greece, with Tsipras being crushed under the German-EU-IMF panzer attack.

In Chile the working class and its allies had mobilized despite Allende, and were transforming life in the country for poor and working people, and this made the coup and subsequent dictatorship necessary. This hasn’t happened in Greece, making the crushing of working class conditions so much easier.

So “will anything be learnt?” That depends on us – no one else will do the “teaching” for us, will they?