Crude oil prices have dropped to five-year lows in just a few months. And the reason is clear: it’s supply and demand! On the supply-side, the most significant development has been the accelerating expansion of shale oil and gas production in North America, mainly in the US.

Oil and gas reserves are trapped in layers of shale rock and can be released by a process of hydraulic water pressure called fracking. By sinking hundreds of rigs in quick succession, shale rock can produce significant supplies of tight oil and natural gas – and this process in North Dakota, Texas and other areas has turned US oil production round. US oil output up to now had been based in traditional deep oil reserves in Texas, Louisiana and the Gulf of Mexico. US production was in decline from the mid-1970s to around 4mbd and falling. But with shale, annual output has rocketed back to 9mbd, near previous peaks. Fracking for tight oil and gas is now spreading across the globe as those countries with large shale reserves look to exploit it in Poland, China, Europe and even the UK.

The other side of the price equation is demand. Global demand for energy, particularly oil, has slowed. That’s mainly because global economic growth has slowed since the Great Recession ended. China has led the way with slowing growth, along with the other large emerging economies, like Brazil and India; and the major advanced capitalist economies remain in ‘low gear’ (see my post, https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2014/11/08/the-world-economy-in-low-gear/). Industries are increasing their use of fossil fuels at a slower pace than expected, while transport demand is in decline (Americans are driving less). Energy conservation has been stepped up and energy intensity (energy per unit of output) is falling everywhere. All the international energy agencies now expect oil and gas prices to stay at these new lows for some years ahead.

The biggest losers are those countries that rely on energy exports to make their money: Saudi Arabia, the rest of the Arab oil states, super-rich Norway, super-poor Venezuela, Mexico and, above all, Russia. The Saudis have launched a counter-offensive. With more than five times the reserves of American shale, they are taking on the shale producers by increasing production in order to drive down the price to the point where shale producers start losing money (their production costs are way higher than the Saudis: about $50/b to $25/b). So far this has not worked and shale production continues to rise. But the Saudi policy is destroying the revenues of other OPEC producers like Venezuela – and Russia.

Putin may have faced up to ‘the West’ over Ukraine and refused to budge but, as I argued in a previous post (https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2014/11/10/from-poroshenko-to-putin-its-all-downhill/), the West has been winning the economic battle and the oil price has been the major weapon. The collapse in the oil price has exposed the weakness of the Russian economy.

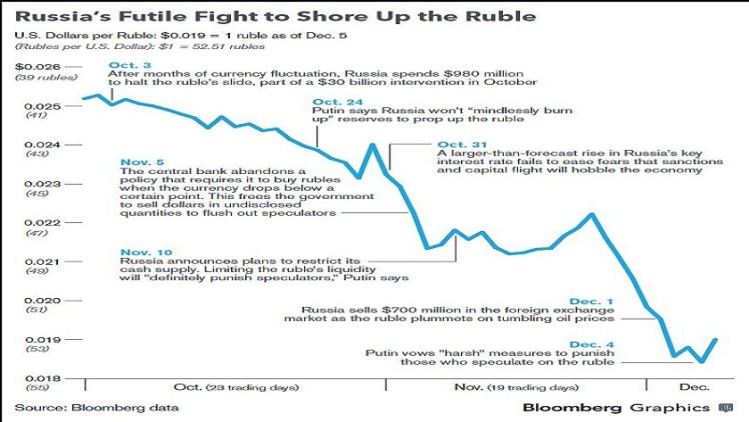

Just a year ago, Russia’s stockpile of dollars from energy exports stood at more than $515bn. Now as oil revenues have dissipated and sanctions on Russia imposed by the West over Ukraine have been applied, Russia’s trade surplus has diminished and the flight of capital by oligarchs and others out of Russia and the rouble has rocketed to $120bn a year. As a result, FX reserves have dropped below $400bn and the rouble has plunged in value to the dollar by 40% this year, invoking a sharp rise in the inflation of prices in Russian shops and shortages of imported goods.

$400bn is still a large reserve and the Russian central bank has tried to prop up the rouble by selling its dollars and buying the Russian currency in FX markets. But it did not work. Then the central bank just let the ruble go to save dollars. And the rouble plunged further. Now it has started buying roubles again with its reserves to stop the fall, again to no avail.

Central bank policy is all over the place. And this is worrying Putin who has begun to criticise his own bank appointees. The problem is that much of these reserves cannot be used to prop up the currency because enough must be kept to cover payments for essential imports (the IMF recommends at least three months worth of imports). If reserves drop below that level, the rouble will go into even more meltdown as foreign lenders (mainly European banks) pull out their money. Also the fall in the ruble means that all those Russian companies with big dollar debts and loans, particularly Russian banks, face huge dollar bills that they cannot meet.

According to the Russian Central Bank, the country has to repay $30bn of debt this month and another $138 bn in the next 18 months. Only 2% of this debt is owed by the government, while non-financial enterprises accounted for more than 60%, the rest mostly belong to the banking debt, including Russia’s largest bank – the state-owned bank Sberbank.

So they are asking for (and getting money) from the government to bail them out. State oil giant Rosneft, for example, has asked for $44bn, equalling more than half the remaining balance in the so-called Wellbeing Fund that’s earmarked to support the pension system. VTB Bank and Gazprombank have already gotten more than $7 bn from the Wellbeing Fund and are asking for billions more. If FX reserves and wealth funds are used up to bail out the banks, then planned infrastructure projects will be dropped and pensions will come under threat. And the three-month import limit will get closer. At current rates of decline in FX reserves, that limit could be reached by summer 2015.

Putin‘s annual address to the Russian parliament last week showed he was getting worried. He even offered a complete amnesty to oligarchs who have been spiriting their money out of Russia like a waterfall in the last few months. “I propose a full amnesty for capital returning to Russia,” Putin said. “I stress, full amnesty.” “It means,” he continued, “that if a person legalizes his holdings and property in Russia, he will receive firm legal guarantees that he will not be summoned to various agencies, including law enforcement agencies, that they will not ‘put the squeeze’ on him, that he will not be asked about the sources of his capital and methods of its acquisition, that he will not be prosecuted or face administrative liability, and that he will not be questioned by the tax service or law enforcement agencies.”

In Russia, two of the major classes of people who have large amounts of capital overseas are organized criminal groups and the so-called oligarchs. In stressing that there would be no prosecution, Putin appeared to explicitly leave the door open to money obtained illegally. “He’s talking to people who have engaged in corporate raiding,” said Professor Louise Shelley, founder and director of the Terrorism, Transnational Crime and Corruption Center at George Mason University in Fairfax, VA. “There are thousands of cases where people who have used criminal processes and false documents to acquire assets. He’s talking to organized crime figures who have taken over businesses.” She added, “There are no large fortunes that are entirely clean money in Russia.”

Assuming the oil price stabilises at around $60/b next year, Putin can avoid a debt crisis next summer, if he can squeeze Russian corporations to buy roubles with their dollar export revenues (a form of capital controls) and to bail out the banks with government reserves. Putin is doing just that. But that does not save the domestic economy. The sanctions plus the collapse in oil prices have pushed the Russian economy into recession. The government admitted that the economy would contract by about 1% next year, with investment falling 3.5% and average household incomes down nearly 3% in a year! Indeed, for the first time in 15 years, living standards for the average Russian will fall in 2015. A freeze on inflation-linked pay has been imposed and inflation is rising at nearly 10% a year now.

Putin may be very popular because of his foreign policy over Ukraine and ‘standing up’ to the West, but his popularity will now suffer because of his domestic policy. Russian-style austerity is coming. Whereas government spending has risen an average 10% a year in the past decade, it will now be cut. Cutting military and police spending is politically impossible because Putin needs the support of the security establishment so he can rely on them in case of social unrest. This means the government will have to target investments, benefits and salaries. Last week, Putin announced a 5% cut in real terms from 2015-2017 by reducing “ineffective spending,” except for defence and security. Putin used to promise Russians that their country would overtake Germany as the world’s fifth-largest economy by 2020. In May 2012, he signed a decree pledging to increase real wages by half by 2018. Those promises are now dead in the water.

Putin continues to rely on his Ukraine policy for popularity and Ukraine’s economy is in an even worse state. Ukraine’s central bank reserves have dipped below the $10bn mark for the first time since 2005 after making a gas payment to Russia’s Gazprom (see my posts on Ukraine). The IMF will probably hand over another $2.7bn in funding to tide the Kiev government over. But it is clear that Ukraine needs another $20bn over the next two years to handle the war in the east and fund debt repayments. An IMF mission arrives tomorrow to plan a massive austerity plan for the Ukrainian people in return for funding.

But probably the most important aspect of the collapse in the oil price is the spectre of global deflation. World inflation has been very low since the Great Recession, another indicator of the Long Depression that the world economy has been locked into. But what inflation of prices there has been has mainly been due to the sharp rise in energy prices. Non-energy price rises have been minimal. Now, with the sharp fall in energy and other commodity prices (metals, food etc), deflation is the spectre haunting the globe.

Oxford Economics finds that if oil prices were to fall to as low as $40/b, then 41 out of 45 countries it follows would experience deflation.

Some argue that this is good news. This is the line of some neoclassical economists and the Austrian school. Falling prices, particularly in energy and food, will raise consumer purchasing power, and help boost demand and thus economic growth.

But for profitability, it is bad news. Inflation of corporate producer prices is another temporary counteracting tendency to falling profitability. If it disappears, then the downward pressure on profitability from any new technology investment will be greater as falling prices squeeze profit margins. In that sense, deflation is not good news for the capitalist sector, especially if it is burdened with heavy debts (small businesses in particular). So the crisis brewing for Russian businesses may be followed by others. It could be another factor leading to a new global slump, this time based in the non-financial productive sector of capitalism.

The Oxford table is highly suspect: neither Russian nor the US experiences deflation at any price point.

And this: “She added, ‘There are no large fortunes that are entirely clean money in Russia.’ ” is priceless– as if there are large fortunes anywhere that are “entirely clean.”

Falling oil prices reduce constant circulating capital lower the occ and increase profits. How is that had for capitalism?

In the US and Canada, what little recovery there has been is almost purely down to the shale oil/ tar sands oil boom. With the now collapsed prices of crude oil, it is not only Russia that is hurting, but it is also the especially marginal and costly unconventional oil extraction boom of North America. This is precisely why the western sanctions on Russia focused on the financing and sales of drilling equipment to Russian oil companies.

Absolutely correct Bill, as Marx sets out in Capital III, Chapter 6, where he also sets out the opposite case that it was rapidly rising input prices that caused a fall in the rate of profit, as well as causing output prices to rise choking off demand, and thereby preventing the full input price from being recovered, thereby squeezing profit margins and causing a crisis of overproduction.

Lower oil prices cause a problem for capitalists involved in oil production, but there only those whose individual value is higher than the social value for oil. They will go bust, their assets will be significantly depreciated, and be bought up by bigger capitalists who will thereby increase their own profits.

There is, however, a bigger problem as I’ve set out in the blog post Could The Slide In Oil Kill The Bond Market, because energy now accounts for 16% of the US junk bond market, comapred with just 4% a few years ago. According to Deutsche Bank, about a third of these bonds are already distressed, and ready to spark another round of defaults.

Given the highly illiquid nature of the junk bond market, any such big sell off could be dramatic, and would undoubtedly roll across into the rest of the financial markets, because oil and oil derivatives are used widely within financial markets as derivatives.

Correction: should say “used widely as collateral.”

The “bigger problem” is that the oil industry, being so technically intensive, has a “dominant” weighting in establishing the general rate of profit. And no, this isn’t a case, of “other” capitalists will benefit as oil faces a depression.

All profits will be, or more precisely, become depressed, and the short term benefit to the auto industry, the airlines, etc. will be wiped out by the generalization of the decline in profit through the mechanisms of the market which will dictate a severe contraction of the entire economy.

This will become evident, first and foremost, as petrodollar flows, recycling oil profits through all of capitalism wither.

“Falling oil prices reduce constant circulating capital lower the occ and increase profits. How is that had for capitalism?”

Precisely to the extent that it represents an overall devaluation of capital. Those who think 2008 was “a blip,” as I recall Bill writing, might as well ask, how can deflation, devaluation of capital be bad for capitalism? How can destruction of capital be bad for capitalism?

Sure thing. No this is not the glass half empty or is it half full question. And no, it doesn’t depend on if you’re pouring or drinking. It depends on how thirsty you are, and why you’re even pouring to begin with. If your reason for both pouring and drinking is to accumulate, to enhance profitability, well you have a problem because the glass is obviously broken, and the stuff your selling isn’t worth drinking.

Our “blipologists” might as well ask, ” how can the catastrophic decline in maritime shipping rates; the collapse in charges per TEU on containerships; the decline of iron ore prices; decline in aluminum production in Europe; or office space rental collapses; hurt capitalism?

Simple answer: because they are part and parcel of overproduction, of a decline in the rate of profitability, and are both examples of the destruction of values, and a harbinger of the further destruction to come.

Bill,

There is another point, which is that its not just the value of the circulating constant capital that is reduced, thereby reducing the OCC and raising the rate of profit. Its the value of circulating capital as a whole that is reduced, because oil and oil based products form a part of the value of the wage fund. As a consequence of the fall in oil prices, the cost of fuel used by workers for transport and heating, as well as in plastics and so on falls, not to mention causing a fall in the prices of all other commodities bought by workers, in which oil and oil based products form an input. In other words, it constitutes a fall in the value of labour-power, and so potentially a rise in relative surplus value, thereby contributing directly to a rise in the rate of profit.

But, there is also another aspect to this. In their theories of crisis, Marx and Engels point to the fundamental contradiction faced by capital, between the production of surplus value and the realisation of surplus value as profits. On the one hand a fall in wages increases the production of surplus value, but because workers form an increasing majority of consumer, a fall in wages also reduces potential demand, and thereby makes the realisation of that surplus value, as profits more difficult. On the other hand, a rise in wages, that increases aggregate demand makes it easier to realise a greater proportion of surplus value as profits, but at the same time reduces the amount of produced surplus value.

The shift to the extraction of relative surplus value from absolute surplus value, is a means of reconciling this contradiction, and formed the basis of Fordism. So, a fall in the value of labour-power, which does not result in a corresponding fall in nominal wages, increases real wages – hence aggregate demand – without reducing the amount of produced surplus value. Although, the rate of surplus value does not change, therefore, and so has no effect on the potential rate of profit, by facilitating the realisation of that produced surplus value, it increases the actual rate of realised profit.

Alternatively, depending upon the actual relations of supply and demand in the labour and commodity markets, the fall in the value of labour-power may not result in any reduction, in nominal wages – in fact because as Marx, Keynes and others pointed out wages are sticky downwards in such conditions they usually will not fall – but may result in a real terms fall, as capital raises nominal prices for commodities, or does not reduce prices in line with the reduction in commodity values. That is facilitated by reducing the value of money tokens by increasing their supply.

Workers may, thereby obtain an increase in real wages, but not to the full extent of the decline in the value of wage goods. The consequence then is that real wages rise, but so does relative surplus value. In that case, both produced surplus value and the rate of surplus value rises, but because workers real wages also rise, the potential for realising that surplus value as profit also increases.

That was how Fordism worked. So, a fall in oil prices reduces the value of labour-power, which not only reduces the OCC and raises the rate of profit by reducing the value of constant capital (it also reduces the value of fixed capital, because oil and oil based products are used in its production too) it also reduces the OCC and raises the rate of profit by reducing the value of variable capital.

In addition, the fall in the value of labour-power, either increases the rate of surplus value, or increases the rate of realised profit, by facilitating the realisation of produced surplus value, or usually it achieves both these functions, simultaneously.

Putin made those promises of improvements in living standards when there was peace in Russia’s near abroad (aka lost lands) and no uber-hostility from the West. Do you think that the Russian people are so stupid as to not have noticed that the West is doing everything in its power to undermine not only Russia’s president, but Russia herself?

I’m not familiar with “Russia herself” as a Marxist category. What is “herself”? Is Russia capitalist? If so, the undermining is part of the mechanism for distributing profit and the interest of the workers is not in the distribution of profit, but in the abolition of the system for extracting profits.

And what abaut Slovenia?

The Banks will be next.

sartesian is likely right that high OCC petro production plays a key role in setting the prevailing general ROP, and hence its own impending fall will be the next ratchet down in its (re)equalization. Thus any temporary benefit to capitals from the fall in the price of this element of their constant circulating capital will be purely conjunctural, and will not provide the space for a structural expansion.

Further, those “branches of industry” not well-regulated by the law of value, because they sell their commodity capital (or their pseudo-commodites) into the “consumer” market, that is, largely to the “middle” and working class with little market leverage, will themselves capture the rent-equivalent surplus profits surrendered by the oil industry, reminding ourselves that oil price embodies a significant differential rent component. So we will see a further intensification of the “scissors” divergence in prices between actual manufactured commodities and those of the pseudo-commodities sold by the cartelized health, education, transportation, communications, government and finance “industries”, capturing surplus profits by means of rent or commercial arbitrage, or both.

Matthew,

The process you describe is wrong for several reasons. Firstly, for a fall in the rate of profit in oil production to bring about a fall in the overall rate of profit would require that the capital involved in oil production represented an overwhelming proportion of the total social capital. It just doesn’t, and never has.

Capital involved in Manufacturing in total in the US, including oil production amounts to less than 20% of GDP, whereas capital involved in service industries accounts for 80%! The same is true in most other developed economies. Even in Saudi Arabia, manufacturing in total, including oil production, only accounts for 62% of GDP, with services accounting 35%, whilst in terms of employment the situation is reversed with manufacturing industry accounting for only 21.4%, and services 72%.

Secondly, the test is to look at what happened in the past. In the 1970’s, when oil production did constitute a much larger component of the total social capital, what happened when oil prices and profits rose sharply? Did this rise in oil capital profits cause a rise in the general rate of profit, promoting a boom? No, exactly the opposite.

The rise in oil prices was not the cause of the onset of the long wave downturn that started around 1974, but it was the spark of the economic crisis that arose after the oil price shock. Rather than it causing a rise in the general rate of profit, it led to the exact opposite, as it sharply increased the price of an important input cost. It was exactly the same effect as Marx describes in Capital III in relation to the sharp rise in the price of cotton due to the US Civil War, which significantly increased the cost of constant capital for Britain’s most important industry, textiles. The price rise could not be passed on in to final textile prices, squeezing profits, rising prices choked off demand, causing a retrenchment of capital.

Thirdly, the process you describe misunderstands the means by which a rise in the rate of profit in one sphere leads to a rise in the general rate of profit as set out by Marx. The means by which a rise in the rate of profit in one sphere brings about a rise in the general rate of profit, is via competition, movements in prices of production, and a reallocation of capital. That is if the rate of profit in oil production rises sharply, this means that its current market prices must be above its price of production, because only at the price of production is this capital making average profits.

The consequence is that capital from other spheres, which are not making these high profits available in oil production migrate towards it. This has two effects. Production and supply of oil rises, the market price of oil falls, until it reaches the price of production for oil, and thereby capital involved in oil production once more obtains the average rate of profit. But, the process itself requires that capital thereby leaves those other areas, where the rate of profit was lower. In other words, it necessarily requires a contraction of these other industries. By this means the supply of commodities by these other industries contracts, the market price of those commodities thereby rise until they reach the average rate of profit.

Rather than a rise in the price of oil, which leads to a rise in oil profits thereby causing a rise in general profits that sparks an increase in investment, that causes a general accumulation of capital and economic growth, therefore, it causes the opposite, which was seen in the 1970’s, and 1990. In the same way a fall in oil prices has the opposite effect, as can be seen from the effect of the reduction in US energy prices over the last few years.

Reblogged this on Alejandro Valle Baeza.

I will look forward to an imminent drastic reduction in petrol prices and utility bills then. And instead of borrowing the money to purchase the stuff I want I shall now pay for it out of my real wage increase. And this is all good for capitalists.

Am I reading this correctly?

Petrol prices in the US already have fallen significantly, (gas prices had already fallen by around 75% in previous years due to the huge rise in gas production from fracking) and are seen as a basis for increased consumer spending, as workers have more money left in their pocket to buy other commodities, i.e. an increase in real wages. Petrol prices in the UK have not fallen by as much, because the largest element of the pump price is tax, and a fall in oil prices does not directly affect the level of duty.

That the costs of fuel and energy falls for capitalists is good news for them is correct. It means they have to advance less capital to produce a given amount of profit, so their rate of profit rises. That its good for most capitalists, because a fall in the costs to workers of travel and heating falls, so they have more to spend on other commodities, or have to borrow less to buy those commodities (thereby enabling the productive-capitalists to realise a greater profit, rather than a portion of it being siphoned off by money-lending, fictitious capital) is good news for the majority of capitalists is correct.

That provides a basis for further economic growth. That is no doubt one reason that the US has had GDP growth of over 3% in four of the last five quarters. The last Philly Fed Index doubled from its previous level, which is pretty much unheard of, and if it is a correct reading implies Q4 growth of 6.5%, which is probably unlikely, but gives an indication of the direction of travel of the US economy despite the effects of the three year cycle.

Its perhaps also why the US created 320,000 new jobs last month, and the figure for job creation in the previous two months was revised up sharply too.

Black Friday sales were 11% down on this time last year. And have lack of sales been the problem during the last 6 or 7 years? Won’t workers simply be borrowing less, thus impacting on rentiers?

“Petrol prices in the US already have fallen significantly, (gas prices had already fallen by around 75% in previous years due to the huge rise in gas production from fracking) and are seen as a basis for increased consumer spending, as workers have more money left in their pocket to buy other commodities, i.e. an increase in real wages. Petrol prices in the UK have not fallen by as much, because the largest element of the pump price is tax, and a fall in oil prices does not directly affect the level of duty.”

Priceless, or a sign of dementia, or both. Increased US consumer spending? Since 2009 median annual household income in the US had declined to the 1996 level. Despite rising in the 2Q 2014, the first rise in SIX YEARS, median household income is 8% below the 2007 level. Since 2009 that income has risen for only the top 5% of households. So exactly how has the decline in natural gas prices increased disposable income or consumer spending in the US? It has not. It will not.

The rate of increase for personal consumptions expenditures during this so-called natural gas boon to real wages IS LESS THAN HALF the rate of increase achieved in the 1990-2000 period

If it weren’t for the persistence of reality, Boffy would have a great theory of capital accumulation.

Henry,

The point is that if oil and gas prices are falling that creates the potential for rising real wages, as what was previously spent on oil and gas products, can now be spent on other commodities, i.e. rising real wages.

What was the situation of wages and consumption in the last 6 or 7 years is irrelevant to that discussion, because its about what the effect of the current fall in oil and gas prices will have on future consumption!

What sales were on Black Friday, i.e. one day is a bit irrelevant too, especially given the switch to online shopping.

If consumers use the rise in real wages resulting from lower oil and gas prices to reduce existing debts, this has no effect on the rate of profit. If money lending capitalists lose out on potential interest, as debt is paid down that has nothing to do with profits. Profits and interest are two completely different things, as Marx sets out in Capital III.

In fact, as workers reduce their debts by this means, they also reduce their future interest payments, which means that they thereby increase their future real wages further, because having less interest to pay, they have a greater proportion of disposable income to use to buy commodities.

As Marx sets out, interest is a deduction from surplus value. If the fall in oil and gas enables workers to reduce their borrowing, and so their interest payments then this feeds through into higher profits for industrial capital, and thereby into a higher rate of profit.

That is in addition to all those other factors, by which the fall in oil and gas prices reduce the capital-value that must be advanced by industrial capital (as Marx makes clear the average rate of profit is calculated on the capital advanced by all industrial capital, which includes merchant capital and money-dealing capital {which of course is different to interest bearing-capital, as Marx sets out, the latter being only fictitious capital} so any reduction in the capital that must be advanced by any of these forms of actual capital, not only raises the rate of profit, but also releases advanced capital, which is then available for accumulation.

The main danger for capital, as I’ve set out on my blog is its effect on the financial sector, by killing the Bond market, but as I believe that such a financial crash would ultimately be cathartic for capital, in the way that Marx describes, and lead to an increase in productive-investment, it is only a danger for a section of capital, or more specifically for fictitious capital.

So are we now likely to see retailers ending their sales offers and selling things at their value? But then wouldn’t this offset the oil price reduction?

What blithering nonsense from Boffy: “The point is that if oil and gas prices are falling that creates the potential for rising real wages, as what was previously spent on oil and gas products, can now be spent on other commodities, i.e. rising real wages.”

Oh right, except for this minor detail called Depression, or recession, or contraction, or devaluation where workers lose their jobs; where real wages decline, as they have declined in actuality in the past, both recent and beyond. Except for this thing called capitalism.

Like I said, persistence of reality vs. Boffy’s pollyanna dementia. You make the call.

Sometimes I can’t quite process all of Boffy’s misinformation on the first go round… or even the second. For example, I missed this beaut, where Bobby attributes the strengthening of the US economy to the recent decline in oil prices:

“That provides a basis for further economic growth. That is no doubt one reason that the US has had GDP growth of over 3% in four of the last five quarters. The last Philly Fed Index doubled from its previous level, which is pretty much unheard of, and if it is a correct reading implies Q4 growth of 6.5%, which is probably unlikely, but gives an indication of the direction of travel of the US economy despite the effects of the three year cycle.”

Well, look the 40% decline in oil price has been over the past 5 months– for that decline to have such rapid to the point of immediate impact is in fact impossible in that US industry has over the years steadily reduced the proportion of production costs attributable to energy consumption per UNIT of OUTPUT.

But that’s just a technical detail, I’m sure.

Henry,

“So are we now likely to see retailers ending their sales offers and selling things at their value? But then wouldn’t this offset the oil price reduction?”

I don’t see how your premise here follows from anything I said. In fact, I would say that the “sales” by retailers, in so far as they are not just marketing gimmicks, are an indication of an excess build up of commercial capital, built up since the 1980’s. It is another aspect of low interest rates during that period caused by the massive rise in the mass and rate of profit globally since the late 1980’s, and the relaxation of credit regulations, and promotion of consumer debt particularly in the US and UK. As interest rates rise, much of that commercial capital will get shaken out, and the capital will move to productive purposes.

Retailers no more than productive-capitalists sell commodities “at their value”, but only at market prices that revolve around the price of production for the commodity. A fall in energy prices which reduces the cost of constant capital, and reduces the value of labour-power, thereby causes both the rate of surplus value and the rate and mass of profit to rise. As Merchant Capital claims its share of this general rate of profit, as opposed to interest bearing capital, which only obtains interest as a price for capital sold as a commodity, then the rise in the rate of profit, would facilitate merchant capital, selling commodities at lower prices without that squeezing profit margins by such an extent as previously.

In other words, a reduction in energy prices reduces cost prices. Consequently, if selling prices remain constant, the realised profit, and the rate of realised profit rises, because profit is the difference between cost price and selling price. The realised profit rises, but the capital advanced to produce it has fallen, so the rate of profit must rise. Alternatively, if selling prices fall in consequence of the reduction in cost prices, the mass of realised profit may then remain the same, but the rate of profit would still have risen, because this constant mass of profit was produced with less capital.

In reality, competition, and the price of production will determine whether the reduction in cost prices caused by the fall in energy prices causes final selling prices to fall, or remain constant. In one case the mass of profit rises, in the other it remains constant. In both cases, the rate of profit rises, and an amount of capital is released for additional accumulation.

No doubt many sales promotions are indeed gimmicks, but they are gimmicks that have seen a noticeable increase since the economic crash. These sales promotions are linked to the decline of real wages, people tightening their belts, so if these retailers perceive that the oil price reduction increases real wages and peoples disposable income won’t that mean they reduce the sales promotions? So couldn’t a fall in oil prices increase prices elsewhere?

Also, if workers now have more disposable income will we see discount stores replaced by more up market ones, will the trend to cut price stores be reversed because of falling oil process? And if not, why not?

Boffy gives us this: “Secondly, the test is to look at what happened in the past.”

Then he gives us this: ” (gas prices had already fallen by around 75% in previous years due to the huge rise in gas production from fracking) and {similar declines in petrol prices–SA note}are seen as a basis for increased consumer spending, as workers have more money left in their pocket to buy other commodities, i.e. an increase in real wages.”

Of course when it’s pointed out that the fall in (natural) gas prices does not correspond to increased real wages (nor does it correspond with any uptick in capital), Boffy gives us this: “What was the situation of wages and consumption in the last 6 or 7 years is irrelevant to that discussion, because its about what the effect of the current fall in oil and gas prices will have on future consumption!”

Well, which is it? Is the test what happened in the past, or is the past irrelevant because it’s not the future? Or is it both? Or neither? Or sometimes something else entirely? If we’re down Boffy’s rabbit hole on planet Boffy in the Boffy galaxy bet on all of the above. Sometimes it is, sometimes it isn’t.

it’s quantum mechanics, and Boffy gets to play dice with his alternate universe. Roll them bones, baby needs a new pair of shoes.

Those of us still attached to planet capital might want to examine the actual data. Like for instance….

US wellhead price, natural gas, $/1000 cubic feet:

2008– 7.97; 2012– 2.66

US residential price, natural gas, $/1000 cubic feet.

2008–13.89; 2012–10.65;

US industrial price, natural gas $/1000 cubic feet

2008–9.65; 2012–4.64.

Only a spoil sport would point out that the 66% decline in the wellhead price translated into a 52% decline for industrial consumers, but only led to a meager 23% decline in the residential price.

Only a killjoy would point out that this occurred during the most severe post WW2 downturn and weakest recovery for US capitalism.

And I don’t know what you would call the person who would be so heartless to point out that real wages did not increase for US workers during this period; consumer spending did not increase; and the general economic condition is, shall we say, precarious? Marxist? How about we try “Marxist”?

As for the current “boom” attributed to, and anticipated to continue, due to declining oil prices, what sort of sadist would point out that Japan, highly dependent upon petroleum imports has managed to tank into recession despite the benefit of reduced prices; that Europe’s industrial production has not benefited from the reduced prices; that auto production in Europe is still and will continue to be, choking on overproduction, overcapacity?

A year or three ago, we heard about how strong commodity prices– particularly for copper, iron ore, etc. were part of a “super-cycle” and “long wave.” Then, the price inflation was a “good” sign, and all the arguments about reduced input costs increasing real profits and real wages were tucked away, sleeping. Now the deflation is supposed to be a good sign. Everything’s a good sign for this optimists club. For the workers, not so much.

“Secondly, the test is to look at what happened in the past. In the 1970’s, when oil production did constitute a much larger component of the total social capital, what happened when oil prices and profits rose sharply? Did this rise in oil capital profits cause a rise in the general rate of profit, promoting a boom? No, exactly the opposite.”

Actually, after the recession in 1974-1975, the high price of oil did contribute to a recovery– as petrodollars were recycled through the US economy– through banks and into, in the US, particularly agriculture and into the then “emerging markets” of Latin America.

This recovery was then brought to an end and with an exclamation point by the “OPEC 2” spike in oil prices in 1979, the double dip recession of the 1980s, leading to the “lost decade” in Latin America, etc. etc. etc.

The decline of oil prices around 1985-1986 hardly precipitated an economic boon and led to the subsequent collapse in real estate, and the S&L debacle.

The spiking of oil prices to $40 barrel neither put the economy based on the first invasion of Iraq followed, and then we had the recovery of 1992-1998 when the rate of profit did in fact recover, but not to previous highs, a recovery based on real advances, and expansion, of the technical components in industrial production, advances prefigured in the oil industries application of seismic imaging, and computer based identification of deposits which brought actual lifting costs to their previous lows achieved in….1949.

Of course the oil prices collapsed as overproduction overtook profit rate equalization and gave us OPEC 3 in 1999, the recession of 2000/01 to 2003.

The recovery from that recession had several interesting features, not the least of which included , besides the draconian limits on further capital spending in US industry until 2006, steadily increasing oil prices, culminating in the spectacular blowouts of 2007-2008. IIRC, energy company profits at their peak in that recovery accounted for about 35% of all the profits of the non-financial S&P profits (so much for Boffy’s assertion that oil companies are too small a portion of US industry to affect the equalization of profit).

Word: portions of GDP are not relevant to profit equalization process. Value production is. What portion of profits are generated by the service sector? What portion of value is generated in the largest portion of that largest portion service sector– the finance, insurance, real estate (FIRE) sector? Answer for the FIRE sector– ZERO, they only aggrandize the already existing profits. That’s so basic to Marx, it precedes his Economic Manuscripts. He alludes to it in his Eighteenth Brumaire where he rights of getting rich, not by producing wealth, but by pocketing the already produced wealth of others.

Boffy’s and Bill’s argument, that deflation or the general decline in oil prices will be “balanced” or counteracted by, or will lead to, increased profits in other sectors doesn’t hold much oil, for the very mechanisms that B&B claim will perform this “trick” are the very mechanisms that turn the “trick” into its opposite. There are real losses, real losses of value that cannot be conjured away, or balanced .

Capital is contradiction in motion, said Marx. The truth is the whole according to Hegel, and that whole is the contradiction in motion.

Or… we can just wait and watch for any empirical confirmation of the B&B pollyanna theory of capitalism. Boffy of course thinks that 1999 marked the beginning of a “long wave upturn,” (that’s from his blog), so I can’t wait to see how this iteration of another predicted upturn develops.

Right now, it doesn’t look so good, does it? I mean oil is part of a generalized slowing, with dramatic consequences; like the catastrophic decline in freight rates for maritime shipping between Asia and Europe; the collapse of iron ore prices, nickel prices, With upturns like these, who needs depression?

“But for profitability, it is bad news. Inflation of corporate producer prices is another temporary counteracting tendency to falling profitability. If it disappears, then the downward pressure on profitability from any new technology investment will be greater as falling prices squeeze profit margins.”

Can anyone point me to a good source explaining why this is the case? It seems quite counter-intuitive considering that oil is an input to new technologies.

When only one in eight jobs ‘created’ in the last eight years are full time in the UK the rest part time mickey mouse there is indeed a ‘boom’ of sorts. Masses of newcomers arriving to take on this work. Which is so profitable that it has to be subsidised by tax and council tax credits to make it profitable otherwise they couldn’t turn up to work! There is so much surplus capital left over from the minimum wage that they can live like decent human beings…not in bedsits…

http://www.stratfor.com/weekly/viewing-russia-inside#axzz3M66Vvq4k