Last week the US Federal Reserve raised its growth forecasts for the US economy for this year and next. Fed officials now reckon the US economy with expand in real terms by 6.5%, the fastest pace since 1984, a few years after the slump of 1980-2. This is a significant rise from the Fed’s previous forecast. Also, the unemployment rate is expected to drop to just 4.5% by year-end, while the inflation rate ticks up to 2.2%, above the official target rate set by the Fed.

Driving this new optimism on growth is the fast roll-out of vaccines to protect Americans from COVID-19 plus the huge fiscal stimulus package put through Congress that most mainstream forecasters expect to add at least 1% point to economic growth and bring down unemployment.

But Fed chair Jay Powell made it clear that the Fed had no intention of raising its target interest rate until 2023 at the earliest even if inflation accelerates. He wants to see the unemployment rate drop to 3.5% and inflation averaging 2% or so. He would tolerate the economy “running hot” until that happens because he reckons that any rise in inflation would be transitory.

The implication of Powell’s view was that the US economy was going to have a ‘sugar rush’ from the fiscal stimulus and from the ‘pent-up’ demand of consumers with cash savings ready to spend on restaurants, leisure, travel etc once the pandemic restrictions were relaxed. But as every parent knows, giving a child too much sugar leads to a rush of energy. And then comes the letdown and sleep. That is what Powell worries about, namely that after this burst of energy on the ‘sugar high’ of government paychecks and restaurants meals, the US economy will slip back into the low growth trajectory that applied before the pandemic slump.

Powell is also concerned about a potential relapse in the fight against the virus and expects fiscal support from the stimulus starting to fade next year and worries that the labour market will continue to struggle. So he expects ‘core inflation’ (excluding food and energy prices) will fall back to 2 per cent next year and 2.1 per cent in 2023. So no inflationary spiral.

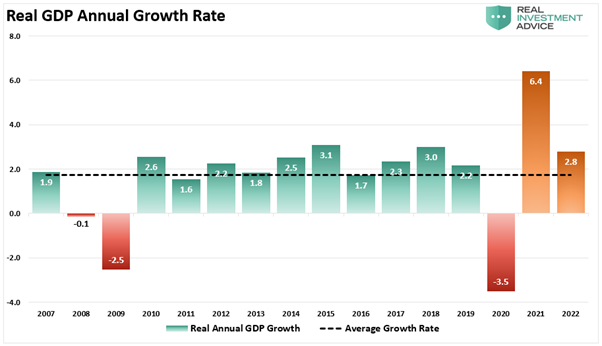

It is significant that the long-term growth forecast by the Fed is just 1.8% a year, which is hardly any higher than average real GDP growth of 1.7% since the end of the Great Recession and before the pandemic.

This implies that the Fed reckons the US economy is going to drop back to the rate of growth experienced in the Long Depression since 2009, and the ‘sugar rush’ is just that.

What this also implies is that contrary to the views of the Keynesians, the multiplier effect of the fiscal stimulus will soon dissipate and then the US economy will depend, not on consumers’ pent-up demand but on the willingness and ability of the capitalist sector to invest. It’s investment not consumer demand that will matter in sustaining any significant recovery; not sugar treats but on new energy in the form of new surplus value (to use Marx’s term for profits).

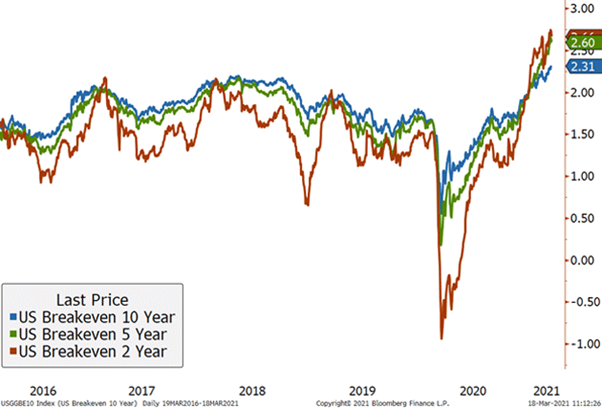

Financial investors are less convinced that Powell is right. After all, getting the US economy to achieve a 3.5% unemployment rate and 2% inflation has been achieved only twice since 1960! So ‘inflation expectations’ among investors have been rising, suggesting an inflation rate of 2.6% on a five-year view. As a result, US government bond yields have also risen significantly, as bond yields suffer in real terms if inflation rises.

The view that the US economy may ‘overheat’ has been argued by Larry Summers, the arch-Keynesian of several administrations. He fears that the fiscal and monetary stimulus will lead to ‘excess demand’ and so drive up prices across the board, eventually forcing the Fed to raise interest rates. Summers argues this, because this time last year, he was telling the world that the COVID pandemic would have little long-lasting impact and the economy would bounce back once it was over, just like seaside towns go to sleep in the winter and then wake up when the tourist season starts. He seems to think that the US economy will revive of its own accord and fiscal stimulus is unnecessary. But the experience of the last year has been much longer and more damaging than a ‘winter break’.

At the other end of the argument, Summers has been scathingly attacked by post-Keynesians and leftists who reckon there is no danger of ‘overheating’ and rising inflation, because there is plenty of ‘slack’ in the economy ie workers needing jobs and businesses needing to start up. But what this view ignores is the ‘hysteresis’ effect on the economy from the pandemic slump; namely that many workers have been forced to leave the workforce for good over the last year and many small to medium businesses will never return. The Long Depression has seen a steady reduction in estimates of US productive capacity.

That means the room for economic recovery is reduced unless investment in new means of production and employment rises significantly. So there could be ‘overheating’ and higher inflation, not because of pent-up consumer demand but because of weak productive capacity – not ‘too much demand’ but ‘not enough supply’.

What the last ten years has shown is that business investment growth has slowed as the profitability of productive capital has fallen in the US. Cash-rich companies and investors, borrowing at record-low interest rates, have preferred to speculate in financial assets. The huge tally of bailouts by central banks and cuts in corporate taxation have been spent on driving the stock and bond markets to all-time highs while the ‘real economy’ has stagnated. The bottom 80% of American households, who drive the bulk of personal consumption expenditures (PCE), continue to struggle to make ends meet.

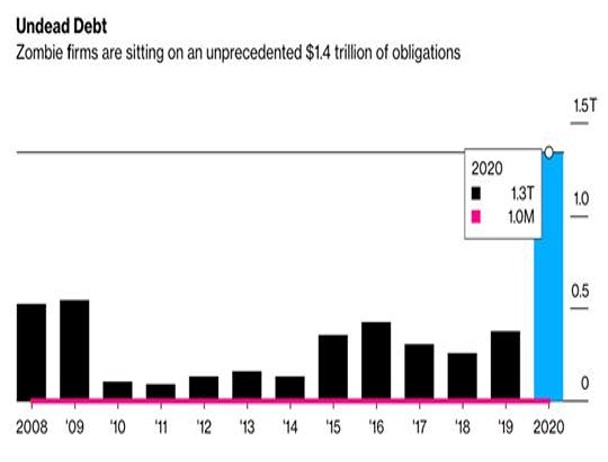

And down the road, rising debt cannot be ignored. And it is not so much public sector debt, which in the US is now well above 100% of GDP; more important is corporate debt. If interest rates for firms do start to rise because of increased inflation, then debt servicing costs for a whole swathe of so-called ‘zombie’ companies will become an excessive burden and bankruptcies will ensue.

According to Bloomberg, In the US, almost 200 big corporations have joined the ranks of so-called zombie firms since the onset of the pandemic and now account for 20% of top 3000 largest publicly-traded companies. With debts of $1.36 trillion. That’s 527 of the 3000 companies didn’t earn enough to meet their interest payments!

As before, the Fed is caught. If it does not end the monetary largesse at some point, then inflation could rise which will eat into real incomes and drive up corporate debt costs. But if it acts to curb inflation, it could provoke a stock market crash and corporate bankruptcies. That is what happens when an economy is in ‘stagflation’: namely rising inflation and low growth.

A stock market crash caused by rising interest rates does not always lead to an economic recession. Mainstream economist Paul Samuelson used to joke that the stock market has predicted 12 out of the last 9 recessions. Indeed, as Marx argued, financial crashes have a law of their own and do not always coincide with ‘commercial crises’.

For example, the very sharp fall in stock prices in 1987 did not lead to economic recession and prices recovered quickly. The reason then was that the profitability of capital in the major economies had been rising for over five years and was at a relatively high level in 1987 and profitability continued to rise for another decade. But that is not the situation now. The profitability of capital is near all-time lows and even a recovery in 2021 and 2022 will not put levels back to that before 1997 or 2006. And corporate debt has never been higher historically.

These underlying forces suggest that the ‘sugar rush’ will be just that – a short burst followed by slumber at best.

“If it does not end the monetary largesse at some point…”

There’s the rub. Moral hazard is in full effect. Too big to fail has essentially been codified by the politicians the capitalists have purchased. So, theoretically, how long can it all go on, assuming the power elite all agree to keep the game up? I’m surprised they’ve been able to do it this long…

Doesn’t the role of government debt in maintaining the nominal values of fictitious capital, either directly or by preserving nominal value of the currency, mean that many of the winners in the depression (those that have capital reserves always win distressed properties in a depression, no?) will find an excessive debt an unbearable burden long before they find the gigantic flow into the banks, the stock market and corporate bonds a threat. Given the perception that the rest of the world will always bear the brunt of US government contraction, isn’t there likely to be a major political demand for austerity?

If the US weren’t the financial nerve center, I would expect a monetary crisis in exports, but there is no reserve currency to compete. Making a basket of currencies work or switching to Special Drawing Rights to replace the Fed have the problem of opposing the US government while coordinating in a kind of monetary union with other states, which is not what good bourgeois democracies do. Gold and oil, the commodities most likely to be sought to preserve value are either too scarce or their markets too manipulated by a handful of players. Although an inflationary crisis/dollar collapse seems unlikely (and fears of hyperinflation wildly inflated, barring a military defeat of the US,) It’s clear to me that a stagflation scenario is probable.

I think it is Powell who is having the sugar high. If we examine Retail Sales for the combined months January and February a strange combination is seen. In terms of adjusted data, the two months were up by 5.1% on the previous year, but if we examine unadjusted figures sales were flat. Thus it appears it is all in the adjustment, with the fall in February effectively wiping out the rise in January. https://www.census.gov/retail/index.html

Thus a $900 billion injection was effective for only one month. Yes there will be a short term boost from the $1,900 billion ARP Bill, but that has to be set against so many negative potential events. First and foremost, the issue of interest rates. The 10 year rate is above, what I called the red line at 1.6%, and markets, while not sneezing have certainly got itchy noses. I would caution against using 1987 to substantiate the view that market crashes do not cause recessions. Conditions now are very different and the economy, because of inequality, is much more dependent on capital gains. Thus a market crash will wipe out any gains from these relief packages. I have been trying to look up losses in the global bond market, which amounted to $3 trillion when the rate hit 1.4%. It is likely now to be in the vicinity of $5 trillion.

Anyway we will know more this Thursday when corporate profits are released. Once again I will prepare a post which looks at the rate of profit both with and without subsidies.

Hi Michael, love the blog- I just had a quick question about the US stimulus package I was hoping you could help with.

It’s about the stimulus cheques- if I remember right they’re about $1,400 each. This helicopter money sounds good, but am I not right in thinking that a lot of this will just go into the pockets of private landlords or other rentiers and will thus have a limited effect in terms of boosting consumer spending?

I think you are right. The sugar rush is more for the higher income earners, not the bottom 50% of consumers. Another reason why it won’t last.

Thanks Michael for this much-needed post. There seems to be an excitement with the Biden stimulus package, not only in (post) keynesian circles but among leftists as well. I guess that’s understandable, due to the ever-growing desire for a break with neoliberalism. That said, it’s always preferable to be on the realist side and avoid an over-iflation of expectations.

However, I was wondering wether that ‘hysteresis’ effect you refer to, will eventually result in a rise in the profitability of capital, based on both constant and variable capital being ‘destroyed’ or ‘dissipated’ (in mechanical terms). Any thoughts on that? Thanks!

Your question is right to the point! I think this is a possibility but so far the survival of zombies suggests otherwise. Watch the level fo bankruptcies and profitability of capital data.

There is no goddamn way within the next 6 quarters there won’t be a massive crash. Fictitious capital has exploded in size, consumer debt is out of control, and millions are out of work, meaning there is no surplus value to be captured.

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/minimum-wage-2019-almost-half-of-all-americans-work-in-low-wage-jobs/

Even before the pandemic, the lowest 44% of all Americans were already in dire straits on a median income of $18K/year.

Anybody who thinks a $1400 check is gonna somehow save the economy, let alone boost it, needs a reality check.

Your analysis regarding “zombie companies” taking down the economy echos many of my own thoughts on how our amazing stock market bubble is most likely to end. I’m not so sanguine about the real economy escaping the fallout from that crash, however, and I also fear that rising bond interest rates could have a significant impact on the government’s ability to respond via fiscal policy. Two future possibilities, not mentioned in your blog, will probably have a big role in how it all plays out. First, will Congress enact Biden’s proposed $3T infrastructure package? My guess is they will, if not before the crash, then very likely after. Second, will the Fed, once the crash forces it to drop interest rates back to zero again, effectively retire enough government debt via QE to keep the government’s debt payments under control? While it does not enter the real economy in such a direct way, that kind of helicopter money potentially dwarfs that of our ongoing little $1400 “Easter egg hunt” (as I call it in my lighter moments). Time will tell!

I don’t get it. Why will inflation kill zombie’s companies?

Why not keep interest rate low and pump more money into system? Where is the limit to this strategy?

Maybe you could recommend me some post about negative impact of inflation