Last week, the Bank of England’s chief economist, Huw Pill, doubled-down on the argument that the current inflationary spiral affecting the major economies was the result of excessive wage demands. He said that workers should just accept that price rises will hit their living standards. “Somehow in the UK, someone needs to accept that they’re worse off and stop trying to maintain their real spending power by bidding up prices, whether through higher wages or passing energy costs on to customers etc.” Workers asking for more wages just made inflation worse. Pill echoed the previous comments of his boss, the Bank of England governor, Andrew Bailey, who said a year ago that: “I’m not saying nobody gets a pay rise, don’t get me wrong. But what I am saying is, we do need to see restraint in pay bargaining, otherwise it will get out of control”.”

At least this time, Pill vaguely mentioned that firms hiking prices to sustain (or even increase) profitability might also be contributing to inflation. But it remains the orthodox mainstream theory that accelerating inflation is being caused by ‘excessive’ money supply growth over output growth (the monetarist theory) and/or by ‘excessive’ wage demands forcing prices up (the Keynesian theory).

In a similar message, Ben Broadbent, BoE deputy governor, said there was “no getting round the impact on real incomes of . . . jumps in import prices”, which he said had “led to second-round effects on domestic wages and prices”. But how does hiking interest rates stop import price inflation from increased energy and food prices introduced by the multi-nationals that control these necessaries?

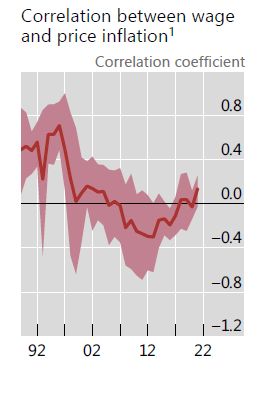

I and others have spent much ink in showing that both these theories do not explain inflation in prices, either now or in the past. And it’s not just leftists. For example, economists at the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), hardly a leftist body, found that: “by some measures, the current environment does not look conducive to such a spiral. After all, the correlation between wage growth and inflation has declined over recent decades and is currently near historical lows.”

But central bankers and mainstream economists ignore the evidence and continue to promote monetarist or wage-push inflation theories. Why is this? Gavyn Davies, former chief economist at Goldman Sachs, once explained why the theory that inflation is caused by wage rises persists even though it has been discredited theoretically and empirically. Davies: “without the Phillips Curve, the whole complicated paraphernalia that underpins central bank policy suddenly looks very shaky. For this reason, the Phillips Curve will not be abandoned lightly by policy makers”. (Davies 2017). Another reason not mentioned, of course, is that the monetary authorities and mainstream economics resolutely refuse to recognize the role of profits in capitalist economies. Profits apparently play no role in investment or in firms hiking prices in order to sustain profitability. And above all, profits must be sustained.

Pill reiterated the policy solution of central banks to get inflation rates down: “Interest rate rises in the US and UK over the past year were designed to cool spending power and the ability of companies and people to pass on the pain of inflation to others”. Exactly who was taking on pain, he did not say; but it is clear that the pain is on workers’ real incomes, not on corporate profits (so far).

In a penetrating paper by Matías Vernengo and Esteban Ramon Perez Caldentey, entitled Price and Prejudice: A Note on the Return of Inflation and Ideology, the authors pose the issues at debate: “there is an ideological divide between those that blame inflation in an incompetent government and central bank reaction to the pandemic versus those that suggest that the real culprits are greedy corporations raising their mark up above their costs.” But “this has deviated the debate from the more important question, which is related to the question of whether the inflationary acceleration originated in temporary supply side disruptions caused by the pandemic or resulted from excess demand in an economy close to full employment.”

The authors go on to say that the dominant view in the profession, and among policy makers is that inflation is caused by excess demand. The main argument against this view is that corporations have taken advantage of supply-side problems during the pandemic to obtain unjustifiable extra gains in an already unequal society.

It’s true that over the past forty years of neoliberal ascendancy, deregulation has allowed corporations to amass pricing power. And it is also the case that that profit margins have increased during the recent inflationary acceleration. And the financial sector has made significant profits during and after the pandemic. But Vernengo and Ramon counter that “it would be wrong to claim as some do on the left that current inflation is ‘greedflation’ ie caused by price-gouging; or that it is the result of monopolistic pricing.”

The empirical evidence shows that it was the sharp rise in the prices of non-labor inputs that were “the likely culprits for the acceleration in inflation”. They rose because of the shutdown of key suppliers during COVID in China and other developing countries and from the loss of electronic components supply that went into the production of consumers goods and because the supply chain system was broken with the collapse of the just in time inventory methods over the last four decades.

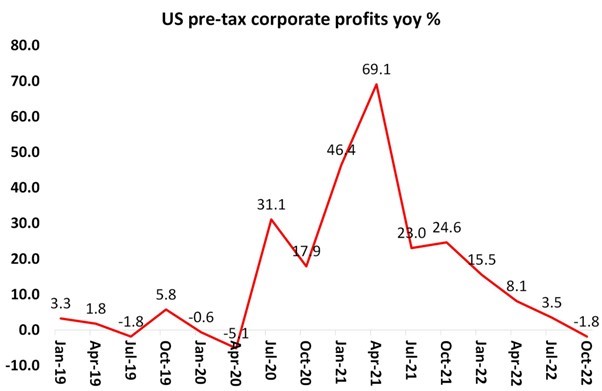

Sure, prices in oligopolistic markets are likely to be higher than in more competitive markets “but it is not the case that this can explain the continuous rise in prices; that would require a change in the competitive conditions, something that is not clearly taken place in the last two years.” Higher inflation can occur both with fairly competitive or oligopolistic market structures. In the late 19th century, the so-called Gilded Age Era was characterized by the rise of cartels, but with deflation in prices; and the 1990s, often seen as a second Gilded Age with increasing market concentration, experienced a so-called Great Moderation in price inflation ie disinflation. Indeed, in the last big inflationary spiral of the 1970s, profits actually fell. According to Sylos-Labini, wiring then: “the decline of the share of profits in several capitalist countries can be attributed primarily to the persistent increase of direct costs in labor, raw materials, and energy”. This contradicts views according to which: “Companies with enough market power can also unilaterally raise prices in a quest for greater and greater profits” as MMT economist, Stephanie Kelton has argued.

In a recently widely acclaimed paper, Isabella Weber and Evan Wasner, Sellers’ inflation, profits and conflict: why can large firms hike prices in an emergency? argue that “To link market power to the sudden increases in profits, it is necessary to examine why large firms have raised prices in the context of the pandemic but kept prices stable in the preceding decades. This implies that market power is not constant but can change dynamically in a changing supply environment.” They point out that that, before the pandemic, there was a long period of relative macroeconomic price stability, with low inflation and generally shared growth in nominal value added between wages and profits.

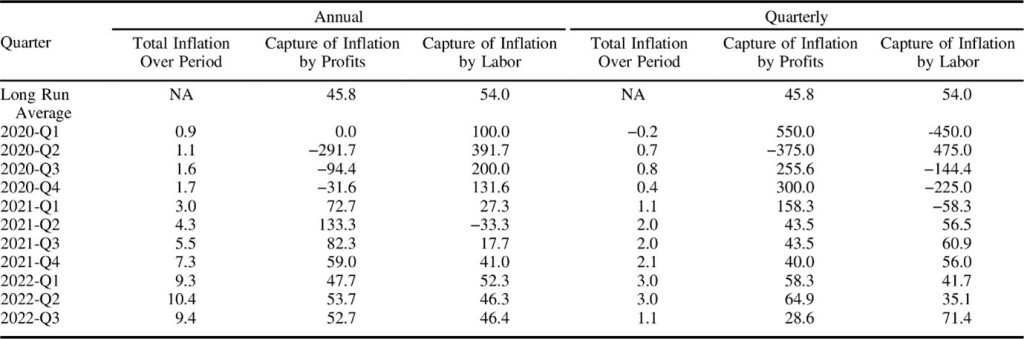

It was only in the post-pandemic period of the last two years that profits have usurped a greater share of the value in price increases per unit of output. But as their table shows, in the first part of 2020, it was wages that gained most from price rises as profits dived in the pandemic slump. Through 2021 those relative shares were gradually reversed and profits reaped the lion’s share. But in 2022, the wage-profit share in the value of price rises was pretty even. Indeed, in Q3 2022, labor’s share in price rises was greater.

So it all depends on the point in the cycle of expansion and contraction that a capitalist economy is undergoing, not on the ability of monopolies to ‘price gouge’ as such. The data suggest that, in the period of supply chain blockages and sharply rising basic commodity prices (food, energy), firms with pricing power hiked prices to sustain and even increase profits (2020-21). But as supply blockages subsided and production picked up in 2021-22, competition increased and further profit mark-ups could not be sustained.

As Vernengo and Ramon conclude: “The persistence of contractionary demand, mostly monetary, policy as the main tool to contain inflation seems to respond more to the prevailing prejudices and the ideological biases of the profession, than to the analysis of the real causes of inflation.” On the other hand,“It is not helpful that the main challenge to this consensus has been to blame corporations for increasing their profit margins, since this view also provides an incorrect explanation for the recent acceleration of inflation. The main culprit for the inflationary acceleration in the U.S. and most advanced economies is related to the supply side snags, and the shock to energy and food prices resulting from the pandemic and the war in the Ukraine.”

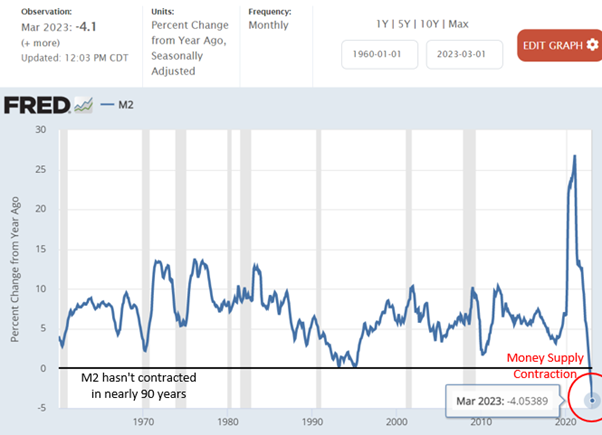

Central bankers and the mainstream ignore all this debate and continue with their claims that it is excessive money, or excessive aggregate demand and wage rises that is causing the inflationary spiral. Their policy answer is to raise interest rates and reduce money supply to restrict demand and, as unemployment rises, weaken wage bargaining power.

What should be the policy against accelerating inflation? Weber and other leftists have argued for the introduction of price controls as the alternative to central bank policies. I have argued against price controls as an effective policy to control generalized inflation, especially as current inflation,is being driven by international energy and food prices. Controlling energy prices at the domestic consumer end would not solve price rises at the producer end, but simply drive private energy supplies into bankruptcy. That would force governments to reverse controls or take over companies. Indeed, that poses the best policy answer: public ownership of the international energy and food companies that operate throughout the global supply chain.

In the meantime, price controls or not, the reality is that, as economies go into 2023, headline inflation rates are falling, as energy and food prices fall back. And so are profit margins as the major economies slip into a slump.

Sure, so-called ‘core inflation’ (excluding food and energy) remains ‘sticky’, so that even in a slump, inflation rates are likely to stay above the average rates prior to the pandemic slump. But it’s the slump that will end high inflation (as it did in the early 1980s), not interest-rate hikes or price controls.

The NYT is now headlining that the main culprit of high inflation in the US right now is the services sector. During the pandemic it was the lack of services.

Meanwhile, high interest rates are slowing down the US economic growth. Low economic growth and high inflation at the same time.

Looks like the “era of abundance” (Macron) is also over for the USA, symbolized by the fall of the USD Standard. The proverbial grain dole to the proverbial citizens of Rome was cut off by the proverbial Vandals.

I think current run of inflation has many fathers. A big factor is monetary policy that drove equity prices up since alternative was no interest on bonds. Investment capital was almost free due to low interest rates. People with capital had surplus savings. Working class didn’t benefit. In US, stimulus programs which were targeted far too high up the income scale resulted in more extra cash. So when supply constraints came, those people with surplus savings could bid up prices of goods while those at the bottom mostly had to cut back on consumption. Corporations with monopoly leverage could squeeze more from those with money than they lost in volume at bottom….Enter the Fed attack on surplus demand focusing on labor costs mostly among workers. Phillips ) might have worked for a while in the 1950s when big union bargaining set the pace for wage increases — of course not now. So interest rate hikes to slow economic growth and cool wages by the higher unemployment rates is a remedy targeted at the wrong income segment. Like injecting pain killer for a tooth ache into a knee…Question: would raising taxes on the upper middle class and wealthy have a greater impact on curbing demand than interest rate hikes which most impact low income people who don’t have the capacity to increase quantity demanded. Their wage increases are barely keeping even with inflation. It is doubtful low-income people are consuming more than they were in recent past. … Hey, it makes a good story:)

https://www.msn.com/en-us/money/markets/us-money-supply-is-doing-something-truly-historic-and-it-may-foreshadow-a-big-move-for-the-stock-market/ar-AA1b2QuH

If price controls could lead to nationalization – that would be good. However, it would probably just lead, in this political context, to bankruptcies of smaller firms and them being gobbled up by bigger ones.

I agree

Central banks devalue the currency every year by a 2% goal. NAIRU is bourgeois bi-partisan policy. Meanwhile, real wages don’t garner more of the collective product of labour as measured in real GDP. That wage rises cause price rises was refuted by Marx way back in the 19th century. All a rise in real wages does is lower the rate of profit.

Exactly

New Zealand then other central banks chose 2% for a very good reason, it was equal to the average annual improvement in productivity. Thus unless workers received a wage rise ot at least 2% most of their productivity ended in their bosses pockets. Incidentally a rise in productivity plus a 2% rise in prices, implies a 4% depreciation in money not 2%. Thus any wage rise below 4% acts to slow down the fall in the rate of profit, to answer the question above.

Earlier today I looked at the Consumer Price Index, in the US, both seasonally and non-seasonally adjusted. Turns out that since June 2022 the indices have increased by 2.4%, which annualizes to 3.1%. So inflation is waning, and the year-to-year number is misleading. Then I looked at the “average weekly earnings for production and nonsupervisory workers”, 82% of all full-time workers and 83% of all 160 million workers. From February 2020 to March 2023 incomes are up 1.5%, which is slow rate of growth. Not enough to drive inflation.

Then I looked at profits for “domestic nonfinancial corporations” at the BEA.gov site, Table 6.16D, and I note that profits were up 72% over three years. And there’s a page at the Fed’s FRED graphs for the same, and it shows a 106% increase in profits from Q2 2019 to Q2 2022. And I’ve looked at the Flow of Funds report, from the Fed, and it shows a 78% jump in nonfinancial profits in 2 years.

I’ve left a comment before at M. Roberts’ site about corporate profits, citing the study of Mike Konczal at the Roosevelt Institute. I tend to side with the greed-flation camp.

The table in this essay, by Weber and Wasmer, fails to reflect the fact that from Feb. 2020 to April 2020, 21 million workers lost their jobs, and more like 28 million when one includes the “misclassified workers”, or 24% of all workers were unemployed, and fortunately this unemployment rate came down quickly. That 24% rate comes from The Center for Budget and Policy Priorities’ article called Tracking the Recovery from the Pandemic Recession.

Josh Bivens in one of his essays says that an excess profits tax would work better than price controls. Bernie Sanders had presented this proposal, it went nowhere, of course.

How to find the 106% rise — look in the Fed’s FRED graphs. How to find the BEA numbers, see Table 6.16D, line 13.

Now to finish this off, the RealTime Inequality web page shows that in 1976 the market income, called Factor Income (pre-tax and pre-transfer income) distribution was as follows: in 1976 the

lower 50% earn 20% ———– middle 50 to 90% (a 40% group) earned — the top 10% earned 31.4%

in 2022, December

lower 50% earned 13.3% — middle 40% earned the 41.9% — top 10% earned 47.9%.

My point is the distribution shifted by 13.5% of total income, about $3 trillion, which comes to a loss of income of $23,000 per worker. — or $46,000 for a two family income. It’s a lot. The median would be around $110,000, not $70,000. It’s conjecture, but the question would be, why wasn’t inflation at 10% per year in 1976? Answer, we need price controls. Or Michael Roberts’ solution. This is Too long a comment.

See my comment in Michael’s second to last post titled WELL FOUNDED PESSIMISM where I show that half the Covid funds amounting to 18 months of non-financial corporate profits was sucked up by business which accounts for the extraordinary rise in their profits, profit margins, and rate of profit despite a pandemic which disrupted production. On my site I also provided rates of profit between 2020-2022 based on profits with and without subsidies.

Correction: the middle 50 to 90% (a 40% group) earned 48.6% in 1976 and 41.9% in 2022.

Michael, you are to be applauded for your systematic defense of the proposition that rising wages depress profits because they do not raise prices.

As the large US corporations release their earnings reports for Q1 2023, I am intrigued and perplexed. Take Procter & Gamble, whom Business Schools consider to be the best run corporation in the USA. It announced that in the quarter it had secured a price rise of 10% on its sales. This delighted Wall Street and was pounced on by pundits who applauded the ‘resilient’ US consumer. On the other side P&G’s cost of sales only increased by 4% on a volume adjusted basis. This cost of sales is a combination of the wages paid to production workers plus inputs. So clearly there was little inflation on the input side but plenty of inflation on the output or selling side. The result was that P&G’s profit margin rose by 7%. So if we use P&G as a test case the argument is settled, inflation here is purely a function of profit gouging. The perplexing point is how did P&G manage to increase its prices on this scale? Its too early to make a determination until corporations in the retail sector release their results. Its not due to a strong or tight labour market. The jobs created have been low paid while the jobs lost have been higher paid. https://pginvestor.com/financial-reporting/press-releases/news-details/2023/PG-Announces-Fiscal-Year-2023-Third-Quarter-Results/default.aspx

The other exhibit is Caterpillar. Its revenues went up 17% of which price rises accounted for 14%, yes 14%. Its production costs actually fell resulting in a rise in its cost of sales of only 5.7% Here we can understand how demand boosted prices. It’s caused by the Biden Administration’s twin Acts to reshore production in the USA. It already shows that a chunk of that will not go into actual construction, but be bled as profit. https://www.caterpillar.com/content/dam/caterpillarDotCom/releases/1q23/1q23-caterpillar-inc-financial-results.pdf

Three conclusions. The two exhibits prove conclusively there are no supply side issues feeding into higher sale prices. There is no wage push inflation. Finally doubt is cast as to the actual level of inflation. The BEA provides a GDP deflator of 5.3% but most of the corporations who have reported reveal price increases in the USA of between 7% and 10%, Caterpillar being an outlier.

What do you make of jake sullivan,NSA-USA speech at atlantic council!

Please send the link

Found the speech will report soon

His speech is significant, a clear break with neo-liberalism marking a reshaping of the relationship between the state and the private sector. Alas for Mr Sullivan a number of problems presents itself. The Federal Deficit is running at 7% currently removing any wriggle room. The lower house of Congress is likely to frustrate Mr Sullivan’s agenda. Most importantly the areas where the funding is focused is already drowning in oversupply globally. And with the global economy weakening this does not encourage new entrants particularly ones with a higher cost base as found in the USA.

The pandemic was just a catalyst. Inflation in the USA persists even after it reopened its economy.

Now, economic growth is also slowing down.

To top it off, the USD Standard is withering. Without it, the American people will not be able to use their money to import what they need at lower-than-normal prices from the rest of the world.

Now, with the fall of the USD Standard, the USA is starting to behave more like a normal country, where it will have to contain spending and rise interest rates in order to contain inflation. But that is just a symptom, not the cause.

The cause certainly is the TPRF. The data from recent times also confirms Roberts-Carchedi inflation theory: fiat currency is used as the counteracting factor of capital’s tendency to produce more and more use values at lower and lower values.

The USA is shrinking. The only question left is when it will reach the “critical mass” where this shrinking will manifest as a collapse (crisis).

what is your opinion of jake sullivan,NSA-USA ?

sorry.

jake sullivan,NSA-USA speech at atlantic council,i think

It is one more piece of evidence of the beginning of the end of the American Empire, for sure.

https://knpr.org/npr/npr/2023-04-28/the-fed-admits-some-of-the-blame-for-silicon-valley-banks-failure-in-scathing-report It turns out the Fed thinks it’s not very good at regulating banks. Maybe a better use for some of its 800 economists would be to put them in charge of US/Mexico border security policy — particularly those still influenced by Phillips curve theory. Incompetence at the border could lower wages, and thus inflation, by allowing a horde of unskilled workers into the US labor market. https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/world/us-prepares-for-more-migrant-crossings-as-border-restrictions-set-to-end/ar-AA1aocrx

Mexicans are skilled in the arts most US workers have lost in 50+ years of the deindustrialization process, during which we workers have been inductrinated to despise physical labor in a despicable, aristocratic way. Your “horde of unskilled [Mexican] workers” make up most of the skilled carpenters, plummers, electricians, etc, etc. of the US construction industry. Mexican labor, skilled and unskilled, produce all the products (good and bad) of US agriculture. In California most arborists and skilled gardeners are Mexicans. Mexican are the strongest of “unskilled” casual laborers, pound for pound, anywhere…

But, of course, there is no such thing as “unskilled” labor. Hopefully a revolutionary Mexican state will bring them back home…which, hopefully, might awaken the unemployed US aristocrats of labor…

I was talking about people from Central America and South America passing through 🙂 Mexicans are good workers and fine people. More seriously, unrestricted inflow of workers of any skill level will tend to depress wages. US could use more techies and probably construction workers — esp where there are shortages. US should increase legal immigration. My smart-ass comment had two targets: the Fed and current immigration and border policy.

Before we go any further into this nativist sinkhole, it might be helpful if some could actually produce evidence “relaxed” immigration policies correlating with a lower of wages. In the last half of the 20th century and first quarter of the 21st. Don’t think you’ll find that evidence in the countries of Western Europe or the US and Canada. On the contrary the post-war “boom era” sees large flows of immigrant workers for Turkey, Yugoslavia, North Africa, India, Pakistan, the Caribbean to the “advanced” capitalist countries simultaneous with improvements in wages, and living conditions for the already-resident workers.

The same nonsense about “lowering wages” was used to panic white workers regarding the domestic “immigration” of African-Americans to the industrial centers in the US.

The real attacks on wages were “nativist” in origin and in execution– Thatcher, Reagan and were accompanied by anti-immigration policies. Asset-stripping, the practice to the theory of neo-liberalism attacked wages, destroyed industrial concentrations, disenfranchised unions. Look for example at the history of the US meat-packing industry over the last 40 years or so. Only after the defeat of the workers, was the industry reconstituted with lower wages and poorer working conditions, and with a large portion of immigrant workers. The attack on labor precedes and is detached from the presence or non-presence of immigrants.

Simple matter of supply and demand in the labor market. Like this riff from Grapes of Wrath: https://genius.com/John-steinbeck-chapter-21-the-grapes-of-wrath-annotated#:~:text=When%20there%20was%20work%20for%20a%20man%2C%20ten,work%20for%20thirty%20cents%2C%20I%27ll%20work%20for%20twenty-five.

See Borjas reference is this piece: https://www.inequalityink.org/resources/immigration%20charades%20-%20September%202015%20-%20latest.pdf

Nonsense. Your article offers not a shred of evidence for the adverse impact of immigrants on lower wage workers. Immigrants take jobs that the “native” working class, high or low wage, has no interest in taking. Simply look at the numbers of migrants engaged in farm work, or low paying service jobs, No “native” workers are displaced,

The article cites CBO and Borjas. More natives would work on farms if the pay was higher.

Thought this is interesting…. Marx on Immigration https://monthlyreview.org/2017/02/01/marx-on-immigration/#Marx%20on%20Irish%20Immigration

I think the Latin-American illegal or legal mass immigration is more of an ideological domestic debate in the USA than anything else.

The Left (Liberals) are unconditionally pro-immigration because they associate it with what made the American Empire what it is now: the land of endless opportunities, the nation that can absorb the best of the best of the rest of the world indefinitely because it embodies the land of absolute individual freedom. Blocking such flow would mean the strangulation of America, so the argument goes. They know, deep down, that unlimited supply of cheap labor is essential to the maintenance of the American Dream, that is, of the idealized American middle class, represented by the expensive but extremely cosmopolitan New Yorker and Californian upper middle class.

The Right (Republicans; Conservatives) are unconditionally anti-immigration because, although they admit mass immigration was essential to form the American Empire a long time ago, it was only so because those immigrants were white, that is, the race of the immigrant is more important than the immigrant per se. They argue, therefore, for the whitening of America as the path to the rejuvenation of the Empire, which implies the full stoppage of Latin-American immigration (or, for that matter, all immigration of non-whites). Hence Trump’s famous speech of “we welcome immigrants to America… as long as they’re from Norway”.

KP: “More natives would work on farms if the pay was higher.”

Let’s see if I got this right:

KP claims immigrants are competition for “native” low wage workers.

DS points out that in the sectors where low wages prevail, “native” workers avoid employment

KP responds “Yeah but there would be competition if the wage wasn’t low.”

What can one say? WTF? If people in hell had ice water it wouldn’t be so hot? If my aunt had testicles she would have been my uncle? If the wages were higher, “native” workers would be interested in these no-longer low wage jobs? And this is what passes for Marxism?

I’ll leave it at WTF?

no lo contendere.

It is our common experience that price rises. It is our common experience that sometimes that there are periods when rate of rise of price is higher. At other times it is lower. Every Marxist knows that with the development of technology value of commodities become lower. So question is how can we explain permanent inflation in accordance with law of value. We must find our answer in the devaluation of money as a result of increase in supply of Money. It temporarily can hide the lowering of wages. Thus it counteracts the tendency of rate of profit to fall. I want your observation. I further want to know your contribution on economics of social media, if any. Whether you can refer any other important work on this matter that I can consult. I shall wagerly wait for your comment.

During the gold/silver standard era, the tendency was deflationary.

Should your link to the paper by Weber and Wasner be the following: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/econ_workingpaper/343/

You seem to have used a link to a paper by Blanchflower and Bryson.

Another boob!

Hi Michael. Thank you for all your posts I have read for years. Could you please write a thing on AI sometime soon? I understand that AI will lead to loss of jobs and therefore markets. I also understand that normally profits derive from surplus value out of the added value produced by the worker. AI would presumably come at greater cost to the manufacturer. But the manufacturer then goes on to produce ever more goods without having to pay the worker. If the manufacturer initially pays more for his AI machine isn’t this in due time made up by selling his products without the inconvenience of having to pay the worker? I understand that until now machines do not add value but without the worker simply sit there and rust. But AI it seems to me won’t simply sit there and slowly rust. It will actively produce goods for the market. Help!

Greetings. Terry Viney

Dear Terry. Read my posts on robots and AI on this blog. And also my recent post on CHatgpt. Just go to HOME on the blog and use search facility

Thank you Michael. Those AI documents are exactly what I needed.

Terry Viney

Sent from my iPhone

I do not know if migration depresses wages or not, but it is certainly not a simple matter of supply and demand. Potatoes do not consume, but migrants and their families do and they pay indirect and direct taxes (even ‘illegal’ migrants in some cases ), so the ‘laws’ governing potatoes and migrant workers are not the same. On the basis of some evidence I read over the years, I would say that migrants do not ‘take your jobs’ and they do not depress wages, except (probably) for the lowest paid work available. Perhaps Michael could write an article on this, it would be enlightening.

As a short aside, I have always suspected (I can’t prove it) that there is something peculiar going on in the South of rural Sweden where the SD (the extreme right, anti-immigrant) gets more votes than the national average. I suspect that at least some over there are very good at voting against immigrants while at the same time exploiting them to the maximum. Legal precariousness can be a blessing. It is certainly not bon ton to mention this.