Back in May the Chinese government set up a special zone to implement ‘common prosperity’ in Zhejiang province, which also happens to be the location of the headquarters of several prominent internet corporations– Alibaba among them. And last month, China’s President Xi Jinping announced plans to spread “common prosperity”, heralding a tough crackdown on wealthy elites – including China’s burgeoning group of technology billionaires. At its August meeting, the Central Finance and Economics Committee, chaired by Xi, confirmed that “Common Prosperity” was “an essential requirement of socialism” and should go together with high quality growth.

Over the past fortnight, the tax administration pledged to crack down on tax dodgers and fined Zheng Shuang, one of the country’s most popular actresses, $46m for tax evasion. The Supreme Court declared the 72-hour work weeks common at many private-sector companies to be illegal. And the housing ministry said on Tuesday that it would cap annual residential rent increases at five per cent. And a new layer of officials has been arrested for corruption.

Also, the government is moving to restrict domestic companies from listing on US stock exchanges, in a move threatening to restrict the growth of tech firms that had come to symbolise record Chinese economic growth rates and the emergence of rich company bosses. The years of unbridled speculation by billionaire privately owned companies in league with various local and national officials to do what they want, including usurping state control of the retail banking system, are over.

Billionaires in general, and the mega-wealthy beneficiaries of the tech industry in particular, are now scrambling to appease the party with charitable donations and messages of support. Nasdaq-listed e-commerce website Pinduoduo saiid earlier this year it would donate its second-quarter profit and all future earnings to help with China’s agricultural development until the donations reached at least 10bn yuan ($1.5bn). The move prompted its shares to jump by 22%. Hong Kong-listed Tencent, reading the same signals from Beijing, set aside 50bn yuan for welfare programmes supporting low-income communities, bringing this year’s total philanthropic pledge to $15bn.

The announcement of the ‘common prosperity’ plans was preceded by the arrest of Hangzhou’s (Capital of Zhejiang) top official Communist Party Secretary Zhou Jiangyong by anti-corruption officials. It is rumoured his relatives had been making themselves rich with investments in local internet stocks.

The crackdown on the tech giants and the attempts of the billionaires to gain control of China’s consumer retailing and banking sectors has quickly smashed the hopes of foreign investors too. The Chinese tech sector explosive stock prices have been reversed.

The professed aim of Common Prosperity is to “regulate excessively high incomes” in order to ensure “common prosperity for all”. And it is well known that China has a very high level of inequality of income. Its gini index of income inequality is high by world standards although it has fallen back in recent years.

China: gini inequality of income index (the higher the index, the greater inequality)

The gini inequality measure is used to measure overall inequality in incomes and wealth. In wealth, gini values are much higher than the corresponding values for income inequality or any other standard welfare indicator. China’s inequality of wealth is lower than in Brazil, Russia or India, but still higher than Japan or Italy.

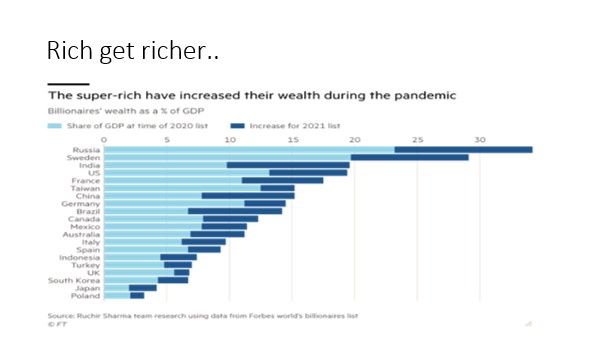

In my view, there are two reasons why Xi and his majority in the CP leadership have launched the ‘common prosperity’ project now. The first is the experience of the COVID pandemic. As in the major capitalist economies, the pandemic has exposed huge inequalities to the general public in China, not just in income but also in rising wealth for the billionaires, who have reaped huge profits during COVID while the majority of Chinese, especially middle-income groups have suffered lockdowns, loss of income and rising living costs. The share of personal wealth for China’s billionaires has doubled from 7% in 2019 to 15% of GDP now.

If this were allowed to continue, it would begin to open up schisms in the CP and the party’s support among the population. Xi wants to avoid another Tiananmen Square protest in 1989 after a huge rise in inequality and inflation under Deng’s ‘social market’ reforms. As Xi put it in a long speech in July to party members: “Realizing common prosperity is more than an economic goal. It is a major political issue that bears on our Party’s governance foundation. We cannot allow the gap between the rich and the poor to continue growing—for the poor to keep getting poorer while the rich continue growing richer. We cannot permit the wealth gap to become an unbridgeable gulf. Of course, common prosperity should be realized in a gradual way that gives full consideration to what is necessary and what is possible and adheres to the laws governing social and economic development. At the same time, however, we cannot afford to just sit around and wait. We must be proactive about narrowing the gaps between regions, between urban and rural areas, and between rich and poor people. We should promote all-around social progress and well-rounded personal development, and advocate social fairness and justice, so that our people enjoy the fruits of development in a fairer way. We should see that people have a stronger sense of fulfilment, happiness, and security and make them feel that common prosperity is not an empty slogan but a concrete fact that they can see and feel for themselves.” My emphases.

As Xi perceptively admitted in this speech about the demise of the Soviet Union: “The Soviet Union was the world’s first socialist country and once enjoyed spectacular success. Ultimately however, it collapsed, mainly because the Communist Party of the Soviet Union became detached from the people and turned into a group of privileged bureaucrats concerned only with protecting their own interests (my emphasis). Even in a modernized country, if a governing party turns its back on the people, it will imperil the fruits of modernization.”

The other reason for Xi’s policy move is that, despite the quick recovery in the Chinese economy from the global pandemic slump, COVID has not been eradicated in China or elsewhere and this has led to a slowing in growth. In August, factory output went into reverse, slumping to an 18-month low, while the main survey of the services sector showed that sector took an even greater hit and contracted for the first time since last March.

Markit business activity indicator (composite) for China – now below 50 (contraction)

Rana Mitter, a historian and director of the University of Oxford China Centre, commented “Party officials fear that the tech giants and the people who run them are out of control and need to be reined in. And then we must add Xi’s determination to be nominated next year for a third term that changes to the constitution now allow.” China’s capitalists imagined that they could act in the same way as those in the G7 economies by investing in property, fintech and consumer media and run up huge debts to do so. But COVID forced the government to try and curb the rise corporate and real estate debt. This has led to bankruptcy of several ‘shadow banking’ concerns and real estate companies. The giant property company Evergrande is struggling to repay $300bn debts and is now expected to go bust, unless the state bails it out. Evergrande claims to employ 200,000 people and indirectly generate 3.8 million jobs in China.

The government had to act to curb the unbridled expansion of unproductive and speculative investment. The latest Financial Stability Report from the People’s Bank of China (central bank) states that between 2017-2019, “the overall macro leverage ratio has stabilized at around 250%, which has won room to increase countercyclical adjustments in response to the epidemic.” In other words, the government could afford the fund the support necessary to get through the COVID slump. But the PBoC admitted that “under the impact of the epidemic in 2020, the nominal GDP growth rate will slow down, the macro hedging will be increased, and the macro leverage ratio will gradually rise. It is expected that it will gradually return to a basically stable track.” So debt is set to rise as China goes into 2022.

The PBoC report claims that it has got all the shadow banking and other risky financial operations under control: “the financial order has been comprehensively cleaned up and rectified. P2P online lending institutions in operation have all ceased operations, illegal fund-raising, cross-border gambling, and underground banks and other illegal financial activities have been effectively curbed, private equity funds, financial asset trading venues and other risk resolution have made positive progress, and the supervision of large financial technology companies has been strengthened.”

But the report is also revealed that there is a section of CP leaders who do actually want to press on with opening up China’s state-controlled financial system to capital (including foreign capital) – and these views are strong within the Western educated bankers in the PBoC. The PBoC report says that it wants to “continue to deepen reform and opening up, further promote the market-oriented reform of interest rates and exchange rates, steadily advance the reform of the capital market, and promote the high-quality development of the bond market. On the premise of effectively preventing risks, continue to expand high-level financial opening.” Apparently, the PBoC officials reckon even more relaxation of the financial regulations will reduce risk!

On the other hand, Xi and his supporters want to control the ‘wild east’ antics of the finance sectors in Shangahi and Shenhzen. Xi is now proposing setting up a new stock exchange in Beijing to lure domestic companies into listing at home instead of overseas. This is part of the strategy to reduce reliance on foreign investment.

According to China ‘experts’ in the West, this crackdown on finance, property and private tech is suicidal to China’s growth. These experts reckon that China cannot sustain its previous growth miracle based on state ownership, planning and investment and instead must let the markets dominate economic policy and investment. The World Bank has been a leader in promoting this strategy for China for decades. The then-World Bank President Robert Zoellick told a press conference in Beijing. “As China’s leaders know, the country’s current growth model is unsustainable.” The so-called middle-income trap describes how economies tend to stall and stagnate at a certain level of development, once wages have risen and productivity growth becomes harder. In early 2012, the World Bank and the Development Research Center, a think tank under China’s State Council, released a 473-page report that spelled out the reforms the country would need to undertake to avoid the “middle-income trap” and ascend to the ranks of high-income nations: ie let market forces rip.

Investment banker, George Magnus, a supposed China expert, has long argued the old chestnut that “at higher income levels, economies become too complex for command-and-control management by individuals. Systems are increasingly what matters. Rules that are transparent, predictable and fairly applied enable market forces to take over the job of directing economic activity, raising efficiency and allowing innovation to flourish.” Magnus, who devoted a chapter to the middle-income trap in his 2018 book Red Flags: Why Xi’s China is in Jeopardy, argues that in pursuing these policies and strategies, “China’s government will stifle incentives and innovation, and make it even more difficult to generate the productivity growth that all high-middle-income countries need to avoid the middle income trap.”

I have dealt with all these arguments in previous posts, so I won’t go into detail again. But the reality is that China is already on the cusp of gaining high-income status, as defined by the World Bank. Based on the World Bank’s current threshold and International Monetary Fund forecasts, the country should achieve that goal before 2025. Indeed, as Arthur Kroeber, head of research at Gavekal Dragonomics in China, has put it: “Is China fading? In a word, no. China’s economy is in good shape, and policymakers are exploiting this strength to tackle structural issues such as financial leverage, internet regulation and their desire to make technology the main driver of investment.” Kroeber echoes my view that: “On a two-year average basis, China is growing at about 5 per cent, while the US is well under 1 per cent. By the end of 2021 the US should be back around its pre-pandemic trend of 2.5 per cent annual growth. Over the next several years, China will probably keep growing at nearly twice the US rate.”

According to a recent report by Goldman Sachs, China’s digital economy is already large, accounting for almost 40% of GDP and fast growing, contributing more than 60% of GDP growth in recent years. “And there is ample room for China to further digitalize its traditional sectors”. China’s IT share of GDP climbed from 2.1% in 2011Q1 to 3.8% in 2021Q1. Although China still lags the US, Europe, Japan and South Korea in its IT share of GDP, the gap has been narrowing over time. No wonder, the US and other capitalist powers are intensifying their efforts to contain China’s technological expansion.

In a report, the New York Fed admits that if China keeps up this pace of expansion, it “is well on track to high-income status… After all, per capita income growth has averaged 6.2 percent over the last five years, implying a doubling roughly every eleven years, and per capita income is already close to 30 percent of the U.S. level.” But the NY Fed argues it won’t be able to as the working population is declining and there will be an insufficient rise in the productivity of labour to compensate. I challenged that forecast in a previous post.

The reason that the NY Fed as well as many Keynesian and other critics of the Chinese ‘miracle’ are so sceptical is that they are seeped in a different economic model for growth. They are convinced that China can only be ‘successful’ (like the economies of the G7!) if its economy depends on profitable investment by privately-owned companies in a ‘free market’. And yet the evidence of the last 40 and even 70 years is that a state-led, planning economic model that is China’s has been way more successful than its ‘market economy’ peers such as India, Brazil or Russia.

As Xi said in his speech: “China is now the world’s second largest economy, the largest industrial nation, the largest trader of goods, and the largest holder of foreign exchange reserves. China’s GDP has exceeded RMB100 trillion yuan and stands at over US$10,000 in per capita terms. Permanent urban residents account for over 60% of the population, and the middle-income group has grown to over 400 million. Particularly noteworthy are our historic achievements of building a moderately prosperous society in all respects and eliminating absolute poverty—a problem which has plagued our nation for thousands of years.”

In contrast, the lessons of the global financial crash and the Great Recession of 2009, the ensuing long depression to 2019 and the economic impact of the pandemic slump are that introducing more capitalist production for profit will not sustain economic growth and certainly not deliver ‘common prosperity’.

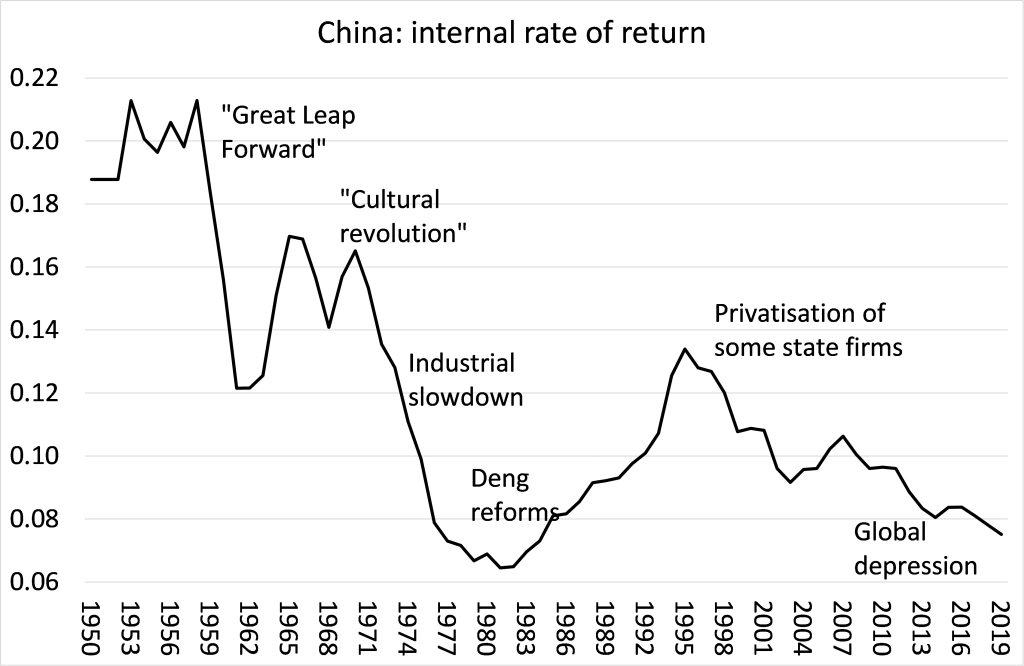

Indeed, it is the capitalist sector in China that is in trouble and threatens China’s future prosperity. China’s capitalist sector is suffering (as it is in the major capitalist economies). Profitability has fallen, reducing the ability or willingness of China’s capitalists to invest productively. That is why speculation in unproductive investment has become ‘uncontrolled’ in China too. Far from the need to reduce the role of the state, China’s future growth through a rise in productivity of labour as the total workforce shrinks in size will depend on state-led investment in technology, skilled labour and ‘common prosperity’.

Source: Penn World Tables 10.1 IRR series

Xi’s crackdown on the billionaires and his call for reduced inequality is yet another zig in the zig-zag policy direction of the Chinese bureaucratic elite: from the early years of rigid state planning to Deng’s ‘market’ reforms in the 1980s; to the privatisation of some state companies in 1990s; to the return to firmer state control of the ‘commanding heights’ of the economy after the global slump in 2009; then the loosening of speculative credit after that; and now a new crackdown on the capitalist sector to achieve ‘common prosperity”.

These zig zags are wasteful and inefficient. They happen because China’s leadership is not accountable to its working people; there are no organs of worker democracy. There is no democratic planning. Only the 100 million CP members have a say in China’s economic future, and that is really only among the top. The other reason for the zig zags is that China is surrounded by imperialism and its allies both economically and militarily. Capitalism remains the dominant mode of production outside China, if not inside. ‘Common prosperity’ cannot be achieved properly while the forces of capital remain inside and outside China.

‘common prosperity’ should be in inverted commas because they’re Xi’s words.

In the title as well.

As long as the workers don’t organise to emancipate themselves from wage labour, they will remain the wage-slaves to those who own and control the wealth produced by labour and that which lies in nature, natural resources.

Reblogged this on maldichos and commented:

Roberts analysis of the economy of China are excellent. he’s a much milder “socialist” than i am but i respect his insights greatly.

History is not linear and does not repeat itself. But it is a science, albeit not a hard one.

The only parallel in History we have to compare with what China’s going on is the USSR during the NEP up to 1929 (i.e. 1923-1929).

During the NEP, everybody outside of the USSR (and many people inside it) thought the conversion to capitalism was inevitable, in fact a done deal, and that the proletarian government experiment was over. It was because of this belief that the main pre-1929 thaw in diplomatic and trade relations between the USSR and the Western imperialist powers happened (specially the UK). The Bolshevik intellectuals were either desperate or already inconsolable for the death of the Revolution, and the white army refugees were already returning to the USSR in order to enforce the restoration of the Tsarist Empire (this is vividly reflected in literature of 1924-1926). The apex of the despair (or euphoria, depending on what side of History the person was) was the year of 1924, which was also the apex of NEP.

The NEP was marked by skyrocketing rise of inequality, the rise of the kulaks in the countryside and the nepmen in the cities. It also marked a sharp rise in poverty, specially in the countryside, and a sharp slowdown in industrialization (which came to a halt in some sectors). Unemployment exploded.

By 1933, all these problems were solved, the NEP not only reversed, but a further push to the “left” (the Bolsheviks never considered themselves to be leftists; they were dead center, everybody else being either to their right or to their left) done with forced collectivization and the reforms which many today put together under the Five-Year Plans (in reality, there were many plans of duration of many different quantities of years – the five-year one consolidated itself after trial and error, and even then there were many five-year plans done by different departments, each one with its chronology). Just to give an example of the radical character of the reforms: in 1929, there was a widespread fear unemployment would plague the USSR for decades and decades to come, due to relative overpopulation in the countryside migrating to the cities;by 1931, there was a shortage of labor power, and the problem was how to train the young faster so they could become apprentices sooner.

The USSR came out from the bottom of the well in 1924 to become one of the two world’s superpowers in 1945. What it experienced in 28 years most countries has ever experienced in their whole existence; none so far have experienced the speed it went through such transformations.

But if we slow down the pace and do some comparative history (I don’t consider comparative history science, but it’s ok for food for thought in a blog comment section), we can come to a conclusion China can revert its capitalistic trends. Sure, it may fail (the same way the USSR could have failed). But one cannot accuse the CPC of not trying. After all, “Every step of real movement is more important than a dozen programs”.

–//–

Now, about workers direct democracy that the author brought in the last paragraph: it is beautiful in theory, but completely impracticable in reality.

The Bolsheviks tried to do exactly what the author proposes on day 1 of the Revolution. Every single factory should be in workers’ control, and land taken over by the peasantry. All the power was given, ultimately, to the local soviets, which were all democratically elected on universal suffrage and participation.

Workers’ collective management was a complete disaster, and didn’t survive one year. It was simply impractical, the logic of a factory required a single manager. It was then rapidly substituted by the now famous single man management.

Local soviets were also impracticable because Russia was a very backward country. Most people were illiterate. The backward peasant social hierarchy completely warped the system. Participation was very low, even by modern Western standards. Most elections were cancelled and told to be repeated again for simple lack of minimum participation. Illiteracy made even the most basic tasks of organizing an election an herculean task, the scarce literate party members having to go travel to the other side of the globe to do it. The Revolution had simply been born in a too backward of a nation.

Land distribution was the only thing that survived, but it survived for all the wrong reasons. Soviet agriculture devolved to a primitive stage, most pieces of land being so small that a using a horse would not be profitable (it would eat more than it would produce). The cities started to starve. Forced collectivization process which lasted for one decades and dislodged 25 million peasants was necessary to solve this problem.

I think a similar problem exists in China. China still is, in essence, a backward country. No communist revolution has ever happened in an advanced capitalist economy, so we’ll never know how things would be done. One thing seems to be certain: specially in its primitive stage, socialism seems to not have a ready-made formula for a system of governance. But, if we think about it, the same happens in the capitalist nations: some nations are presidential republics, others are parliamentary republics, others are constitutional monarchies, others are absolutists monarchies, etc. etc. Capitalism doesn’t need the traditional model of Montesquieu to exist and even thrive; I think the same case will be with socialism.

No, worker councils survived and were working well after the Revolution. Council/Soviet system has beaten parliamentary bourgeois democracy, even. They had plenty of supplementary stuff, even, from the trade unions to “worker control inspections”, which were touring industries to root out corruption and lapses in working class control of the economy.

I have no clue where you’ve gotten your election participation ideas.

Soviet agriculture DEVOLVED? How so, if peasants got their hands onto unproductive land and forcefully redistributed it? As well as taken and liberated the land and labor used for export to Europe, instead sending the products to themselves and to Soviet market? There was an objective, economic need for a land reform, and bolsheviks did that reform. Why the hell would a much needed reform result in degeneration of agriculture? You are clearly reading some weird anti-communist people trying their hardest to find faults with bolshevism here.

“Cities started to starve” is mostly a misrepresentation of Soviet policies. You see, communists weren’t going to surrender to kulaks, so they’ve started taking the grain from them by force if neede, citing the possibilty of cities starving as a (real) justification. Tsarist police and army were sent during famines in Russia into villages to quell rebellions and seize grain, Bourgeois historians don’t like talking about famines in Tsarist Russia for the same reason they don’t like to talk about famines before Mao, or without vastly exaggerating death tolls.

Dislodging 25 million peasants was necessary for industrialization, to secure labor for increased industrial production, not because there wasn’t enough grain to eat. Again, get your facts straight. The tragedy of feudal countries is that massive amounts of people are being tied up in a very unproductive agricultural work. Basically, instead of using more smart way of doing thing, they threw more bodies at the problem, with diminishing returns, and letting peasants go to cities resulted in decreased agricultural production and famines. To combat that, you need to bring new technologies to the countryside, better organization of work and such. Peasants become workers in industries which need more labor, their labor is vastly more productive than when toiling the fields via ancient means. And when those new workers start producing fertilizers and tractors for the countryside, peasants start to get pushed out from the countryside because they are no longer needed there.

Trade unions survived in the USSR, but their function was peripheral. Their function was essentially to do everything Western unions do, except for the fact that they had direct access to the top of the government. So yes, even though all of those institutions continued to exist, they were not in reality all that that was on paper. Tomsky literally was removed from the main Soviet political stage through moral depreciation; as the USSR started to solve its structural problems related to industrial/city workers, unions started to decline in importance quickly and inexorably.

We should be extremely careful in studying Soviet History through its laws. The Soviet Union used a different principle from bourgeois Law, it was not a legalistic state. Even its Constitution wasn’t as sacred as they are in the Western nation-states, they were not absolute, and the rate of dead letters was much greater than in the established advanced capitalist states.

The peasants of the USSR didn’t expropriate unproductive land – the expropriated all land. They did that on their own account, without any Bolshevik interference (because the Tsarist Empire evaporated with the destruction of WWI); the Bolshevik decree determining land distribution was merely legalizing what was already happening. The numbers leave no margin of doubt: in the aftermath of the Revolution, the number of medium and large estates plummeted, and the number of small, unitary land skyrocketed. It was only with time and coercion that the Sovkhoz became the dominant form of cultivation in the USSR.

On the land issue, it’s important to highlight that the Bolsheviks – not matter the fraction – had always in mind that the ideal socialist form of cultivation was large-scale collective farms. The only reason they tolerated those extremely small piece of land cultivation was because, without the support of the peasantry, they would not be able to govern. It was a concession to the peasantry. In fact, the Bolsheviks used the term “Soviet power” instead of “socialism” to describe the actually existing system in the USSR – “Soviet” here meaning a coalition between the peasants and the proletarians. It was a worker-peasant State, not a proletarian state. The Bolsheviks also had in mind the model they should copy for their agrarian reform: the American system. The American tractor and big farms were the concrete embodiment of the socialist dream for agriculture in the USSR.

The local elections were a disaster. In the most advanced industrial regions (e.g. Eastern Ukraine), total participation barely touched 35%, but single digit participation was the rule elsewhere, and in the most remote regions (e.g. Siberia), elections didn’t happen at all. Peasant backwardness resulted in the corruption of the system; for example, it was still common for the patriarch of the family to go vote in the name of his whole household (which essentially wiped out women and non-married men participation). The fact that illiteracy was almost total made even simple tasks as organizing a small election in a local village an herculean task. Even in the VKP(B) illiteracy was widespread, and capable (“westernized”) party members were a scarce resource. Have you ever tried to work with illiterate people? I have, and I can say it is simply not doable, they can’t even do the most basic white collar tasks. Universal basic education exists even in the most aggressive free market capitalist nations for a reason.

1929 was the last year where the VKP(B) tried to revive the local soviets (it was part of the dekulakization campaign, to reverse and completely annihilate the NEP); the results were much better, but the whole thing turned out to be impractical. The system that ended up being the most efficient and practical for the Russian reality was the Presidium-Soviet system, where a presidium of fewer, but more mobile and “gatherable” members essentially governed the correspondent region while the soviet gathered once every year or more to give the philosophical/long-term/strategic direction to the presidium and/or legitimize the decisions the presidium had already taken.

Your last paragraph takes everything wrong. The USSR tried to bring foreign technology to the countryside, but it was embargoed by the imperialist powers who had said technology – that was the main problem. The second problem was that, even when they managed to import said technology, there was a strong reaction from the kulaks, who wanted to preserve the old feudal system – just to give you an example, there is documentation of campaigns in the countryside appealing to religion (orthodox Christianity) to convince the peasant to not accept the tractors. The third problem was the speed required: by the end of the 1920s, the USSR already knew the imperialist powers were planning to invade it; that it only managed to do so ten years later and not five is a mere question of destiny.

The problem of relative overpopulation was solved by 1931, as I mentioned in my original comment, so yes, it was a problem during the mid to late 1920s (diminishing labor productivity due to large supply of cheap labor power), but the Politburo of the VKP(B) quickly realized it and managed to solve it – much faster than even the most optimist imagined. By the acute years of forced collectivization (mid to to late 1930s), this was not a factor anymore.

‘’ The capitalist restoration could not undo the Revolution completely, therefore, culturally Russia is more like China than the West. It is a socialist state temporarily occupied by counterrevolutionaries; think of France after Napoleon. It will not last”.

This striking comment of yours in an article on this blog about China a month ago is absolutely correct. And he is correct in various concepts and facts that are defined by the thesis of the cycle of class struggles (revolutionary cycle). Thesis that I understand that you do not know but thesis of which you suspect and intuit some of its main elements. It is correct that Capitalism, being the majority model, pressures and produces Restorations in the countries that reached Socialism. He is correct that this restoration is, indeed, a counterrevolutionary period in the same way that Capitalism suffered in the period of the European Restoration in 1815-1848 (not only in France but throughout Europe). Restoration that made the Old Regime return to Europe, diluting the liberal reforms (basically bourgeois private property of the means of production) of Capitalism and reforms derived from the revolution of 1789 in France. And he is right, finally, that these counterrevolutions do not last. The European Restoration of 1815 was liquidated with the liberal revolutions of 1848, and according to latest calculations, calculations which include among others the decreasing rate of profit (average), the current reactionary anti-socialist period should not last beyond 2,040 -2060. At that time a new socialist impulse will arrive somewhere in the World-System, an impulse that will be able to bring the common prosperity that, falsely in my opinion, is promised today by Xi Jinpig and his Chinese Communist Party. economic-political cycles with their progressive (advance) and reactionary (regression) phase.

“These zig zags are wasteful and inefficient. They happen because China’s leadership is not accountable to its working people; there are no organs of worker democracy”.

Well I know you are a Marxist which explains your above comment; but central state-planning must always play a significant role in a huge economy like China, to achieve the noble goal of “common prosperity” – a goal entirely absent in the neoliberal “invisible hand” market economies of the West. .

More to the point, I hope China’s home-grown crop of Marxist economists can gain ascendancy over the Western trained neoliberal economists in the PBofC.

The UK is facing the same conflict over monetary orthodoxy, with the UK Treausury currently refusing to print the money to “maintain capitalism on life support” during the pandemic. They need to learn that the dogma of ‘free market efficiency’ has its limitatuions.

Good article but it overlooks one important development. Let’s call it the long march of the urbanised generations. The youth in China, second and even third generation urban workers are rebelling against the working and living conditions their parents accepted, parents who still had memories of rural conditions and hardships. The new generation is increasingly resentful of the “princelings”. Xi is reacting to events not leading them which is why the CCP is intensifying its ideological intervention in schools by remodelling the curriculum to eulogize the party. Expect Xi’ blue book soon or is it a red book.

I’d say a “red book”

You, of course, are being sacrastic. But Xi, though a “princeling” of the bureaucratic 100,000,000 member Chinese Communist Party, is also really an excellent marxist, whose recent speaches really are a kind of red book. What is says to us “marxists” living in core imperial states is,”You can help us best, comrades, by working to democratized your own deeply undemocratic, war-mongering states that threaten us on all sides. Meanwhile, don’t call us “imperialist”. This encourages war. Create a peace movement instead.”

No sarcasm intended.

I have always warned about US aggression against China. The window of opportunity for the US to prevail militarily is running out which is why this period is so fraught. On the other hand I am bouyed up by the growing dissatisfaction if not disaffection amongst workers especially young workers around the world. This includes China.

A China se abriu ao capital e está tentando controlar o mercado. Mas o capital, uma vez posto em movimento, é incontrolável. As reformas atuais parecem muito com a estado do bem estar social, mas são apenas distributivas e não socialistas, como na Europa e USA do pós-guerra. Vai dar certo por enquanto porque a China está enriquecendo como estavam Europa e USA de 1950 a 1980 e estado e marcado podem financiar. Mas todos sabemos que a tendência inevitável do capital é a concentração e a centralização, assim como crises de lucratividade. E a China, agora um país capitalista, vai voltar a concentrar capital e ter crises de superprodução em algum momento do futuro.

By the way, this is an opportunity to see if Mylène Gaulard’s hypothesis is true, as she predicts China will collapse due to a real estate market meltdown a la USA 2008 (therefore demonstrating both that China cannot possibly overcome the “middle income trap” and that it is a normal capitalist country, as she states). Let’s follow up how this Evergrande imbroglio will unravel.

Westerners have been predicting the “fall of China” for literally the past 2 decades straight, some of them are so unhinged as to be nothing but a practical joke e.g Gordon Chang.

Earn a cent for every one of those predictions and you’d put Bezos to shame.

I mean what is this nonsense not even the US properly collapsed after ’08 and arguably after 2020 but China will surely collapse on the first sign of a crisis?

Marxist or not, academic or not, to engage in China doomerism of such a low intellectual level is a shameless activity not worthy of recognition.

But hey if they spend the next 100 years repeating the same nonsense eventually they’ll be right if only because of climate change.

It’s hard not to be impressed by China’s progress, but China’s wealth was built on the back of its people. The capital concentrations they’re currently addressing (at least rhetorically) came from good ol’ exploitation of labor. The root of the problem is that nobody but the actual workers wants that exploitation to stop – and it can’t, if China wants to continue its capitalist defined growth. In tandem with the exploitation of labor comes exploitation of the earth. China continues to grow outside its borders as well, developing a massive network of resource extraction and use. How can they avoid being number one in exacerbating climate change? After all of the rhetoric about equality and socialism, the logic of capital seems to always have the last word.

Exatamente. O capital comanda de agora em diante. O problema da China não é mais ser socialista ou não, mas se tornar o novo império capitalista no lugar dos USA.

It is not capital in the abstract that controls the abstract market, but, as you point out, the very material imperial system centered in the US that controls global production and distribution of wealth and the means to destroy it. China’s problem is not whether to be socialist or not. It is as “socialist” as conditions have allowed, and its problem is to remain so until conditions improve…unfortunately that depends on the very weak and disoriented class struggle in the imperial states. China is being forced to delink or cave in the party’s right wing under very unfavorable conditons.

correction for last sentence: …”cave in to” the party’s right wing.

China does allow the exploitatin of its workers, extract resources, etc., but intentionally in decreasingly in destructively exploitative ways. But it doesn’t grow outside its borders, unless you mean trade. They lead the world in reforestation amd green technology. But it is true “that the logic of capital seems to always have the last word”…at least in your thinking.

The division within the PBoC may reflect leadership qualms over alienating US Wall Street finance in the present conjuncture, on the safe bet that under present circumstances, where Wall Street goes is where US bourgeois politics will go also. Alienation will add decisively to the forces pushing for a “new cold war”.

“And yet the evidence of the last 40 and even 70 years is that a state-led, planning economic model that is China’s has been way more successful than its ‘market economy’ peers such as India, Brazil or Russia.”

I think, although I’m not a 100% certain, that Deng’s plan to draw FDI through low wages has had something to do with this, to the tune of $1 trillion in foreign direct investment over the years.

Walter Scheidel, in his book The Great Leveler, argued that true leveling of property and incomes was “achieved” by catastrophic defeat in war, population collapse…and socialist revolution. Mildly reformist measures he judged simply do not work. If China were a capitalist country, the measures undertaken so far should be lightly regarded, if not dismissed out of hand. They would be a pretense, not a serious program.

But China I think is not a capitalist country and the impacts of these measures are I think vastly more significant precisely because the capitalists so far lack the state power to build the political infrastructure of a truly “free” market economy. Nonetheless, it is not at all clear that a better program wouldn’t be for the state to socialize Alipay, for instance, expropriate the billionaires. Alibaba strikes me as the kind of centralization and concentration of commerce that could be reformed into a superior system of planning for production for use. When Xi says “Of course, common prosperity should be realized in a gradual way that gives full consideration to what is necessary and what is possible and adheres to the laws governing social and economic development…” is greater market control of investment deemed the law governing social and economic development?

I think the mere existence of billionaires is a bad thing, not a good one, but I’m pretty sure Xi disagrees, thinking they are merely too out of control. The notion that as long as the common people are improving their lives then the rich can grow colossally just so long—but no longer—that they don’t threaten to expropriate the Party strikes me more as simple-minded piety, with a Confucian flavor rather than Christian like a US politician. But nothing more. I don’t want to excessively downgrade the wonderful achievement in raising so much of society above the World Bank poverty levels. But the World Band poverty levels are self-interest measures of poverty designed to be sure that not too much poverty is found. (It is not clear to me that if social stress rises so high that most families can’t afford enough children to reproduce the population, that we aren’t then talking about absolute immiseration of an unexpected kind…Fortunately most chatter at population decline is contaminated by bourgeois desperation for cheap labor power, so maybe this only seems to be a potential problem?)

As to the politics Xi said “Ultimately however, it collapsed, mainly because the Communist Party of the Soviet Union became detached from the people and turned into a group of privileged bureaucrats concerned only with protecting their own interests. Even in a modernized country, if a governing party turns its back on the people, it will imperil the fruits of modernization.” Oh, dear, this seems again like more Confucian twaddle. First, coming from a virulently committed partisan of CPC bureaucracy, the Party, versus those unspeakably filthy Maoists who destroyed China, it is not at all clear why Xi thinks he speaks against bureaucrats. Second, the notion that privileged bureaucrats don’t find foreign travel and foreign goods (freely available!) and “growth” from foreign direct investment and foreign guidance much easier than socialist planning is remarkable. Opening and deepening markets is the pursuit of bureaucratic privilege, I think.

I’m afriad the notion that “zig-zags” are the cause of inefficiencies, waste, is very much like the notion that Stalinist zig-zags were the cause of famine in the USSR (unlike famines in Tsarist Russia, which were plainly acts of God, hence divine justice, not crimes.) The notion that central planning forcing industrialization destroyed the economy would, I suppose, explain why the USSR was defeated by Nazi Germany, as it lacked the industrial power to maintain armies in the field. Similarly, the horrors of the Cultural Revolution, when nobodies helicoptered up to the top of the Party and state, left China a ruin that was far outpaced by India, blessed as it was by free markets. The thing about inefficiencies is that inefficiencies include things like keeping reserve stocks on hand and maintaining production capacity. That’s why the capitalist world economy succeeded so well in dealing with the pandemic, rights? And of course, efficiency also meant things like limiting ICU bed capacity so that it was efficiently used, right again? I rather hope none of the more dramatic inferences were not intended by our host. But most people approach these issues with the bedrock assumption all planning is inefficient and only markets are “efficient.”

The conclusion of the comment is correct that much depends on outside forces, as China is still a part of world economy and that’s a capitalist mess. The other about that is, capitalist world economy tends to break down, but breakdown in world economy means world war. Nonetheless, the military and foreign policy of the CPC is its to control. The CPC cooperates in the endless blockade of Korea. It is relying on armaments for defense (even though the US does not show that guns are everything and politics nothing.) It actually invaded Vietnam and though relations are apparently now correct, it is not clear there is any fundamental solidarity. There is no Chinese wall, pardon the expression, between foreign policy and domestic policy. There is no hint the CPC as of today is turning to the left.

In reading the comments, I couldn’t help wonder when India, Russia and Brazil resorted to a high-wage policy to be undercut by Deng et al.? I also had to wonder why anyone would think “democracies” don’t make war and conquer empires? Or why anyone would think peace movements by anyone other than the soldiers count?

Sorry, this is long, but it was a deeply fascinating article on a timely and vitally important subject.

I enjoyed your ironical approach in ironing out the complexities and paradoxes discussed in this post. But there are a few, let us say, “ambiguous” ironies here.

“…..I couldn’t help wonder when India, Russia and Brazil resorted to a high-wage policy to be undercut by Deng et al.”

Did you do this wondering at the time when India et all resorted (or intended to resort) to high wage policy?

Who are the “et al” after Deng? A bunch of amoral empiricists? Including Xi?

“There is no hint the CPC as of today is turning left.”

How about hinting turning left yesterday? tomorrow?

“I also had to wonder why anyone would think ‘democracies’ don’t make war and conquer empires?”

Who is “anyone”? It seems to be you, who seem ironic about “democracies”, but not ironic about these questionable “democracies” conquering empires: imperial NATO “democracies” making war on imperial China?

….Your ambiguous ironies here suggest that you support war and fictitious democracies, but not fictitious socialisms. But I do think you meant anything of the kind, nor to sow the sort of confusions you flippantly attribute to Confucius.

Questions? Then, answers.

The charge that Deng and his successors (who are the “et al.”) industrialized by a policy of low-wage labor is a bit of a joke. There are no countries that tried to industrialize in the twentieth/twenty-first centuries any other way. (You could argue that the US effectively industrialized as a high-wage country but this is no doubt an economic heresy entertained only by people who know more history than economics.)

The current foreign policy of the CPC shows no sign of turning left, in my judgment. I think this has a bearing on how to assess the anti-trust moves in China today. And “today” includes literally yesterday, as well as the whole anti-Maoist period. I make no predictions here about tomorrow.

The “anyone” who don’t seem to think democracies make war and conquer empires is of course you. The notion that democracy isn’t class collaboration to unite the nation against foreigners may offend pieties. It is nonetheless true. That’s why so many people define democracy as democratic government as the institutional restraint of the will of the majority, rather than the instrument to execute it. Or why so many see democracy as the rule of law rather than the rule of the majority. As near as I can tell, most (?) talk about undemocratic governments waging war are very much about sowing illusions in “democracy,” carefully but surreptitiously defined to exclude any reference to classes. The unpleasant truth is that bourgeois democracy most certainly can wage imperial war. The British waging Opium Wars against imperial China most certainly was a war of “democracy.” The notion that just having pure, ideal democracy will resolve such contretemps as imperial conquest is a counterposition, a rejection of the notion of the dispossession of the bourgeoisie and the destruction of imperialism. In my opinion, of course.

correction: “do” should be “don’t” in the last sentence.

Curses, “democracy” *is* the collaboration of classes against the nation’s enemies. Or against the city’s enemies, as in Athens or Sparta or Rome. The “isn’t” above is left from an alternate version first typed, then incompletely re-written. A typo, in other word.

“The charge that Deng and his successors (who are the “et al.”) industrialized by a policy of low-wage labor is a bit of a joke.”

Not a charge or an accusation, but a fact. In the 90s-00s, Japan’s industrial worker wage was approximately 40X China’s. Japan’s FDI took advantage of that in an attempt to offset declining profitability in Japan, and 2/3 of the output from Japan’s enterprises in China was exported.

That China under Deng pursued a policy of exploiting its peasantry in a way that Mao (who also saw the necessity of “opening up”) would not have tolerated, is well known. and lamented. But what is your point? And why ignore the fact that the Chinese population today has been lifted out of the kind of poverty that most of the other nations of the so-called third world still are mired in? Why not go back and blame Stalin on the Bolsheviks? Or accuse Castro, Chavez, Ho Chi Minh, Mugabe, et al for betraying “socialism”?

After all, isn’t socialism a period of contradiction, transition from capitalism, and dictatorship of the working classes…? and bourgeois democracy a period of contradiction and transition under oligarchy….to facism? That’s the choice we all now face in spades. Save your rage for the contradictions of democratic socialism, for Corbyn being cashiered as an anti-semite, for Assange who remains tortured in a dungeon?

correction: the last sentence is not a question

It is not a fact, not in the brute, irrefutable, speaks-for-itself sense you imply here. First, Deng tried this all through the Eighties, with decidedly mixed results, even though the black legend insists that the Cultural Revolution was a catastrophic regression. The rapid growth took place in the Nineties, even to some degree in the twenty-first century. The supposed path of capitalist superexploitation of labor by a totalitarian dictatorship (what is being hinted at) ran as difficult a course as true love.

Second, as was *already* explicitly pointed out, the same supposed low-wage labor sale (a kind of slave auction?) was also the path pursued by all relatively underdeveloped nations, such as India. India is always the place to compare to China when comparing real world socialism and real world capitalism.

This was a charge, and an accusation, that is of dubious relevance to analyzing the economic advances in China vis-a-vis India, etc. But it is standard as a moral indictment singling out China.

But we’re not analyzing the economic advances in China vis-a-vis India, nor more than we are analyzing the growth in output of Mexico vis-a-vis Cuba or El Salvador or Venezuela. It’s good to know that the capitalists in Japan, Taiwan, Canada, the UK, the US, South Korea, Singapore, and others, either alone, in partnership, or through companies based in Hong Kong were NOT motivated by the wage differentials between their home countries and China, as well as the preferential treatment given foreign investment enterprises vis a vis domestic ones in the 90s and 00s. Can’t wait to tell Guoqiang Long former (and perhaps still) deputy director-general of the Department of Foreign Economic Relations of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China, who cited exactly those contributing factors in his paper “China’s Policies on FDI: Review and Evaluation.”

We can go into the reasons it took Deng’s plans years to make a real dent in FDI as a percent of GDP, but suffice it to say, we’re dealing with China, and 10 years is nothing in the history of that country. I would mention China’s proximity to the expanding Southeast Asian economies, Japan’s desperate post 1989 search to offset persistent deflation and recession by investing in production facilities in China for export, but those might be immaterial factors.

Quogiang Long can explain why low wages led to development in China but not India? I don’t think so. I rather suspect Mr. Long is far too naive in accepting advanced “Western” economics, where the moon shines brighter and bigger every nght.

If the ten years (I think this is an underestimate, closer to twenty,) then the ten years (I think this is an overestimate, closer to three,) of the Cultural Revolution is nothing too. I think Mr. Long would laugh at you.

Decades of sustained growth without a crisis is not normal capitalist behavior. Trying to explain this away by talking about how China (covertly to be read as, totalitarianism worse than capitalism in the democratic West, where imperialism is gone and forgotten,) sells off slave labor just like every other poor country isn’t even an attempt at explanation. The German miracle or the Italian miracle of decades gone by, or the more recent Asian tigers, have not had the same outcome, any more than Japan. When China stagnates like Japan, talk.

As I said, we’re not talking about India, nor about Germany, nor South Korea. We are talking about whether or not China’s low wage vis a vis advanced capitalist countries contributed to attract FDI and if that FDI played a significant role in China’s growth. Nothing has been said about slave labor, except by you, or “exploiting” the peasantry except by someone else, or the cultural revolution, except again by you, or any “miracles,” except by you.

So if FDI was not attracted by low wages and the chance to achieve profitability, if FDI did not play a role in the growth, explain 1) why the advanced countries did invest $ 1 trillion? kindness? 2) why the increased exports that correlate with China’s exceptional growth in the 90s and 00s did not contribute to growth 3) what did contribute to growth? Ideology? Moral fitness? Good feelings?

I’ll be sure to tell Mr. Long, now vice-president of the DRC’s state council how naive he must be not to follow the word as delivered by Mr. Johnson.

And there have been crises, plural, in China’s recent economic ascendancy.

Missed this, seen only by accident.

My last comment started with a very simple question, which is ignored. If Anti-Capital wishes not to be read as a typical anti-Communist, Anti-Capital can make things plain, as in: Answering the actual question. Which was, many nations, including China itself since Deng came to power, attracted FDI, yet did not grow, so how the same cause have such different effects?

However, given that Anti-Capital imagines “crises, plural” in China’s recent economic ascendancy, it is highly unlikely Anti-Capital will ever give a reasonable answer. China has not undergone a national economic contraction, which practically every other country has (Australia, maybe?) Nor has it stagnated. Nor has it had a systemic failure of the financial system leading to a seemingly permanent decline where a return to trend refuses to happen, no matter what.

Althusser: “There is no such thing as a socialist mode of production; socialism is a contest between co-existing elements of the capitalist and communist modes of production.”