In my recent post on the US economy (https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2014/05/02/it-was-the-bad-winter/), I poured some cool water on the consensus view that the US economy was set to accelerate its expansion this year. The US GDP figures for the first quarter of 2014 were very weak (although they will probably be revised upwards) and the stronger headline jobs figures released on Friday hid the continued high number of Americans who want a job but have given up looking, as well as those taking low-wage work as better than nothing.

But if we turn to the UK, the current talk is how things are looking way better. Most mainstream economists reckon that it’s all over and Britain is now on a sustainable path of growth. Indeed, the IMF reckons that of the top seven capitalist economies, the UK will grow the fastest this year. Last week, the UK manufacturing activity index was released for April and it showed activity in this key sector growing at its fastest pace for five months, reaching 57.3 from 55.8 in March. This followed the GDP figures where the UK economy expanded by 0.8% in the first quarter, with the manufacturing sector rising 1.3%, while profit margins rose again. Sterling rose to a five-year high and is the best performing major currency in the world over the past 12 months.

So this all looks good and the Conservative-led government continues to crow that its policies of austerity have worked. Even the Keynesians now seem convinced that the economy is turning around for good. Arch-Keynesian Simon Wren-Lewis from Oxford University attacked those who continued to doubt the economic recovery (29 April): “What about the counter argument that the recovery is not real, or not sustainable. In some ways this rhetoric is worse than the ‘austerity works’ line: it is also wrong, but it is much less likely to succeed as rhetoric. The rhetoric will not work because, despite the unequal and uneven nature of the recovery, many people do feel more optimistic now than two years ago.”

Well, feeling good is not the same as being good. The activity indexes may be strong. But, although manufacturing output is growing at its fastest for five years, it is still shy of its peak in 2008 before the Great Recession hit the UK economy. Despite a large devaluation of sterling as a response to the financial crash, exports have not made much progress and the UK’s deficit on trade with the rest of the world remains very high. The UK’s government budget deficit is still the highest among the G7 economies. The real joker in the pack for the message that the UK economy is heading for 3%-plus real growth this year and next is that, just as in the US, the capitalist sector is not investing. In the activity indexes, it was notable that investment goods orders slowed.

Wren-Lewis goes on that “It is much better for critics of the government to focus on the ‘wasted years’ of 2010-2012, and on the fall in median incomes (http://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/cp422.pdf) over the last five years. If they want economic issues for today and tomorrow, focus on inequality.” Yes, they are key issues: the failure of the British capitalist economy over not just 2010-12 but during the Great Recession and the unprecedented (since the 1930s) reduction in the real incomes of the British people over the last five years. But that does not mean we have to accept the view that all is now fine and dandy with the British economy.

The Bank of England published a very interesting paper that showed just how far behind the UK economy is in this ‘recovery’ phase (and see comments on the super blog by Rick, http://flipchartfairytales.wordpress.com/2014/04/29/britain-is-coming-back-well-yes-but/). The figures that follow are in that BoE paper (http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171766_360847.pdf). The UK’s real GDP has still not quite got back to its pre-slump peak in 2007. Yet all the other G7 economies (except Italy) have passed that benchmark. Of course, as I pointed out in a recent post (https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2014/04/11/5-trillion-gone-forever/), none of the G7 can recoup the losses in output, employment, investment and income that the Great Recession caused. That’s gone forever.

And if you look at GDP per head of population, the UK record is even worse, with the UK lagging behind the Eurozone average and still nowhere near restoring the pre-recession position. What that tells you is that the UK economy has only expanded because of a big influx of immigrants into the country. It’s population not productivity that is growing.

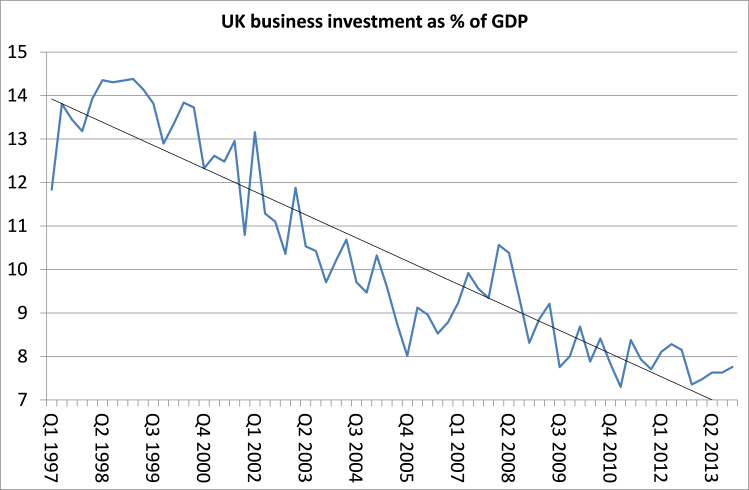

Wren-Lewis does not like this argument: “The fact that growth in output per person (GDP per capita) is less impressive that GDP growth alone does not detract from the recovery because, in a demand led recession, population growth does not automatically cause GDP growth. Recoveries are often led by consumers, but as long as investment follows on and average incomes begin to rise then a recovery will become sustainable.” The trouble is that investment is not ‘following on’. It remains some 20% below its peak in 2008.

Including all investment (in property, business and government), the UK’s investment ratio remains the lowest of all major capitalist economies.

Before the global financial crash broke in 2007-8, I wrote in my book, The Great Recession, that, because the UK was essentially a ‘rentier’ economy i.e. relying increasingly on earnings from rent (property), interest (often from abroad) and foreign capital flows, it would suffer the most from any global crash and take the longest to recover. So it has proved. The BoE shows that the financial services sector, which contributed up to nearly 10% of UK GDP in 2009, much more than even the US financial sector, has dropped 30% to under 7% of GDP.

With the finance sector in the doldrums, the UK economy needed a boost from somewhere else. The answer from the government has been to fuel a new property boom with cheap and subsidised mortgages. Property prices exploded in central London and have slowly filtered to the rest of the country, now rising in double-digit rates. But there has been no corresponding rise in business investment which remained a drag on growth in the UK economy in 2013.

One of the features of the employment market in the UK in this ‘boom’ has been the huge rise in self-employed workers. The number of firms with fewer than ten employees has swelled by 550,000 since 2008. While in mid-2013, there were 5.7m people working in the public sector, only 18.8% of total employment, the lowest since records began in 1999. Indeed, the self-employed will outnumber those working in the public sector in four years, once the government has completed its slashing of public sectors jobs and services.

The right-wing City of London mouthpiece, City AM editor, Allistair Heath tells us that this is really good news for the economy. “This is clearly a golden age for entrepreneurship, especially in London, but there is more to it than that. Self-employment surged 17 per cent over the past five years and is still rising; while at first the increase was made up of people who preferred to work as consultants rather than being forced to sign on to the dole, many of the more recent entrants appear happy with the choice. In the past, recoveries in the labour market were driven by increased demand for workers; today, it is just as much a case of a better, more flexible and more entrepreneurial supply creating its own demand.” Heath goes on to tell us that ‘zero hours contracts’ and choice between self-employment, working on call and part-time work shows how ‘flexible’ the UK labour market has become, thanks to deregulation and the weakening of the unions under Thatcher and Blair. “We need to build on this flexibility.”

Really? Actually, the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor statistics show that the proportion of new entrepreneurs in the UK driven by valuable opportunities has fallen – from a high of 61 per cent in 2006 to 43 per cent in 2012. And ONS figures show that a falling number of self-employed people employ other workers, suggesting that the rise in self-employment is not translating into new, thriving businesses. Researchers at the University of Warwick found that, in less prosperous areas of the UK, policies to increase firm formation had a negative impact on long-term employment, as those who started new companies had low skills, few other options, and poor market prospects.

What is really behind the increase in self-employed is not ‘entrepreneurial spirit’ but the loss of benefits and the ability of self-employed to claim tax credits under the government ‘welfare reforms’. As Richard Murphy at Tax Research has pointed out, the self-employed now account for 14 percent of the employed workforce but 19 percent of working tax credit claimants. In other words, those working for themselves are more likely to be claiming tax credits than those in employment. Actually the self-employed, like the employed are earning less than they did before the slump. In 2007-08, 4.9 million self-employed earned £88.4bn, but in 2011-12, 5.5 million self-employed earned £80.6bn. Indeed, the Resolution Foundation found that that self-employed weekly earnings are 20% lower than they were in 2006-07, while employee earnings have fallen by just 6%. As a result, the typical self-employed person now earns 40% less than the typical employed person. (http://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/2014/05/06/its-not-just-inequality-that-is-rising-rapidly-insecurity-is-too/#sthash.xf5ecfiB.dpuf)

The UK economy is growing faster in GDP terms, but average real incomes are not rising because those in employment and self-employment are, on average, still unable to increase their incomes sufficiently to cover inflation and taxes. Investment by the capitalist sector is not recovering and British businesses are failing to raise their share in world export markets (graph below).

So the expansion of UK economic activity is driven by a credit-fuelled and government-sponsored property boom. That cannot be sustainable. But it may be long enough until next May’s general election.

Michael,

Very impressive data collection as usual, and I agree with your conclusion.

I was struck by the very first chart on manufacturing PMI’s. It illustrates a point I have been making for some time about the three year cycle. A look at that chart shows a clear cycle in which a slow down (not necessarily, a recession) occurs every three years. It can be seen in the chart starting from 2002, and occurring again in 2005, 2008 and 2011. Its due to hit again in the third quarter of 2014, and sure enough, the chart is starting to show that already.

My guess is that this cycle is closely tied to the technology upgrade cycle. But, whatever the cause, then if as I think you are right about the UK growth being largely fuelled by a resumption of government induced private debt, that is likely to quickly dissipate once that slow down begins. In fact, combined by any private debt crisis that may spark – and given the vast number of people reliant on Pay Day Loans, Credit Card debt, plus the millions already in arrears on mortgages despite all the government intervention such a debt crisis is probably, and likely to be much bigger than any problem with public debt – or just the deleveraging effect of people trying to repair their balance sheets, that is likely to cause a sharp reduction in aggregate demand towards the end of this year. Other than the government physically giving money to people to buy houses, its hard to see how this does not cause a property market crash, which will expose the banks as insolvent.

You mention about the depreciation of the Pound. That was true originally, but, of course, more recently both the Pound and Euro have risen strongly against the dollar. That is why the Eurozone is seeing disinflation, and the UK has at last started to reach its inflation target, after it being almost double the target, as a falling pound pushed up dollar denominated imports. A large part of the rise in the Euro, and fall in Eurozone bond rates (including the periphery) appears to be the flip side of the sell off in emerging markets, as even Spain, Portugal and Greece look like safe havens compared to Turkey, Russia and so on, especially as some of these latter economies have benefited from US QE, which is now being tapered.

But, that is likely to reverse at some point, and hot money flow back towards those EM economies, as their much lower currencies, and much higher interest rates (ratcheted up in many cases to around 12%) make them tempting prospects for people who have been suffering from financial repression and are searching for yield. Yellen in testament to Congress yesterday already warned about the danger of the rise in Junk Bond prices due to such a search for yield.

Even, the UK Governments decision on annuities could have unforeseen consequences in that regard. If insurance companies want to attract people back to their annuities business, they will have to start offering higher yields on those annuities, which pushes market rates generally higher.

In short, the recent falls in western bond yields look like a temporary phenomena, resulting from a renewed search for safe havens, but which stick out like sore thumb in a global environment of rising interest rates, and which could spike sharply higher as the search for yield works its way through. Even things like the rash of M&A and IPO activity could affect this. Jim Cramer on CNBC yesterday was saying that the forthcoming Alibaba IPO could crash the market because it is so huge, and will mean that owners of Amazon, Google, and other massively over priced stocks would have to sell them in order to buy Alibababa shares. The reality is that stock markets have been bloated by money printing, and by a relative reduction in available stock as CEO’s have used money hoards, and cheap money to buy back company stock, and boost their share options.

The likelihood is that the dollar will rise, especially as concern is beginning to be heard in the US about the return of inflation, which may cause monetary policy to be tightened faster, or else for it to be done by the Bond Vigilantes for them. A falling pound once more, will push up UK inflation again.

In short, at a time when the economy is slowing at the end of this year, due to the global three year cycle, the UK could be hit by rising inflation, and rising interest rates. Bad news for all those people buried under a mountain of debt, bad news for the British government whose economic policy depends on shovelling more debt on top of that mountain!

Boffy,

Well spoken, yes the QE money is flowing back from the BRIC countries to the US and UK and as Michael explains used to create an other property bubble as if nothing has changed since the Great Recession and trying to go back to “business as usual”, but a bubble must burst sooner or later….

Just to be clear, however, I think for the reasons Marx sets out in Theories of Surplus Value, the bursting of such bubbles is actually positive for Capital. It is in fact, a necessary requirement for sclerotic economies like the UK, and in part the US to begin to recover properly.

In Capital III, Marx and particularly Engels describe the financial crisis that arose in 1847, as a result of the credit crunch caused by the 1844 Bank Act. Preceding it, high rates and masses of profits had been invested in productive-capital – much as the same conditions have led to large-scale investment in such productive-capital in Asia, Latin America, Africa, Eastern Europe over the last 10 years or so – but, then as now, the increase in the annual rate of profit, in the capital released by that process, and in the mass of potential capital available, was so great that not all of it could be physically invested immediately. It led then as now to speculation. Then it was Railway shares, and Engels points out that this speculation was so great that despite high rates of profit from productive-investment, capital began to starve its productive activity of funds in order to feed the speculation. We see the same thing today.

When the financial crisis hit in 1847, despite the fact that the crisis itself was quickly ended by the suspension of the bank Act, and thereby injection of liquidity as happened in 2008/9, the immediate effect on the economy was to reduce economic activity by 37%. But, Marx and Engels point out that this economic consequence of the financial crisis was the prelude to a continuation of the boom, which in fact lasted to around 1865.

Then as now bursting the bubble was a precondition for resources going into productive investment and away from speculation. If you are a CEO, and at the moment have the choice of investing the firm’s capital in the shares of other companies etc., which under current stock market conditions could easily rise by 30%, or to invest in productive-capital which might not provide any returns at all for several years, which would you choose?

Part of the problem, is that even “investing” in financial assets, is no longer about investing for yield, but about speculation for quick capital gains. Even the Asian speculators buying London property are happy to leave it empty, because they are not interested in what rent they may obtain, but only on the expectation that the price of the apartment block will soar.

Until such time as the psychology that underpins that changes there will be a strong incentive to divert resources to such short term speculation rather than long-term investment in productive-capital. A precondition is the bursting of the bubbles.

Boffy,

Interesting, bringing in a most forgotten part of Marx’s Crisis Theory, it reminds me of the Crisisbook of Simon Clarke. My problem with directly drawing parallels between these crises over more than a century is that we have what Carchedi called international oligopoly capitalism with huge banks and corporations, for them restructuring/devaluation as is nor- mally done during a crisis, is not as simple as during Marx’s times, I consider this crisis also as an overinvestment crisis in which capacity utilization rates are not easily restored, to me than the mass of profits (QE) are coming in, with a burst of a bubble the underlying structural problems are coming to the fore. To me bubbles do have a relationship with rising profit rates in the real sector (Asia, ICT revolution) during the 90s. Michael shows that the real conditions in many countries are not healthy after the Great Recession. The UK financial authorities are playing with the FIRE (finance, insurance, real estate) sector once again…..

Henry,

I think its precisely because of the domination of economies by oligopolies that crises of overproduction due to over-accumulation are less likely to form explanations of crises!

If you think about the Marxist critique of market capitalism, it is that such crises arise because production is unplanned and driven by market prices and profits. But, the nature of oligopoly is precisely that production is planned, and that investment decisions are based on long-term plans determined by detailed analysis of where demand is likely to be, and what effect any new supply will have on market prices. In other words, in order to maximise their profits, such oligopolies are forced to borrow the methods of the future society and base their decisions on meeting consumer needs, whilst not expanding their output to such an extent as to damage future profits.

Andrew Kliman is quite right then when he writes,

“Companies’ decisions about how much output to produce are based on projections of demand for the output. Since technical progress does not affect demand – buyers care about the characteristics of products, not the processes used to produce them – it will not cause companies to increase their levels of output, all else being equal.” (Note 4, Page 16, The Failure Of Capitalist Production)

This is quite right. These oligopolies spend large amounts on research and development not so as to expand production without concern for potential demand, which was the basis of crises of overproduction in the 19th century, but in order to reduce their existing production costs, and thereby boost profits, to develop new products so as to maintain and extend market share. Its why, as Marx says, quoting Richard Jones, often when the economy is slowing companies will spend more money to try to maintain their market share. And, as Marx says, its precisely because these socialised capitals in the form of Joint Stock companies, now run by professional managers, with ownership in the hands of share owning capitalists paid a small amount of interest as dividends, rather than receiving profits, that the dynamic of these large companies (and this applies even more to oligopolies) is different to, and no longer determined by changes in the rate of profit, to the kind of small capitals he analyses for most of Capital.

As Engels puts it in his Critique of the Erfurt Programme,

“I am familiar with capitalist production as a social form, or an economic phase; capitalist private production being a phenomenon which in one form or another is encountered in that phase. What is capitalist private production? Production by separate entrepreneurs, which is increasingly becoming an exception. Capitalist production by joint-stock companies is no longer private production but production on behalf of many associated people. And when we pass on from joint-stock companies to trusts, which dominate and monopolise whole branches of industry, this puts an end not only to private production but also to planlessness.”

This change had already occurred by the end of Marx’s lifetime, and he was well aware of it, he just didn’t live long enough to have theorised separately from his analysis of the basic laws of Capitalism derived from the development of the earlier forms of capitalism as they evolved from simple commodity production and exchange under previous modes of production.

It doesn’t mean you don’t get periods of over and under production, but they are driven by the continued existence of a plethora of small capitals that affect the longer-term plans of the larger capitals, and the larger capitals also face barriers to exit, which slows down the reallocation of capital, and you also get the normal market cycles including the kind of temporary gluts and shortages that Kaldor theorised in the Cobweb Theorem.

But, its important to distinguish between stagnation and overproduction. Crises of overproduction as analysed by Marx arise generally in periods of rapid growth and exuberance, and are driven by high rates and volumes of profit. They are sharp crises that resolve the contradiction and allow the boom to continue, as capital gets reallocated, market prices are adjusted and so on. Stagnation, however, arises when there are no potential areas for released capital to enter. That is why they are associated with the Innovation Cycle. In a period after a series of new base technologies have been developed, usually to address some problem in production, a whole series of new industries arise, producing a range of new commodities.

These are the “new lines of production” that Marx describes in Capital III, Chapter 14. They absorb the released capital and soak up the concomitant relative surplus population. They have low organic compositions of capital, and very high rates of profit, and form the basis of the boom, and also validate the capital in the existing industries, by providing a market for its output. But, its when these industries do not potentially exist that capital cannot be reallocated to them, and so capital accumulation slows down, there is stagnation rather than over production. That is why the cycle Marx describes begins with stagnation, moves on to prosperity, through to boom, and then to crisis. These are basically the phases of the Long Wave cycle.

The point is this, is there any lack of potential new commodities, new lines of production into which capital, capital currently can be invested? The answer is absolutely not! We have gone through an unprecedented innovation cycle, which it could be argued is still continuing. We have more inventions being patented than ever in history, there is an explosion of potential new commodities to be produced, for which there are new markets. They all offer the potential for very high rates of profit. In addition we have had, but continue to have a fairly unprecedented expansion of markets globally.

Since 1980, the global working class has doubled. It increased by 30% just in the first 10 years of this century, most of it in Asia. That is a vast increase in the realm of exchange value, because these were previously direct peasant producers. That expansion is now spreading into Africa, which is industrialising in a number of countries at a faster pace in some cases than was even the case with Asia.

Of all the things Kliman has written, this:

“Companies’ decisions about how much output to produce are based on projections of demand for the output. Since technical progress does not affect demand – buyers care about the characteristics of products, not the processes used to produce them – it will not cause companies to increase their levels of output, all else being equal.” (Note 4, Page 16, The Failure Of Capitalist Production)

is one of the few I disagree with: decisions about output indeed are driven by technical progress just as Marx demonstrate it does in that the application of greater quantities of machinery “demands” that the machinery be operated at maximum, or near maximum levels of efficiency in order to (a) transfer the value of the machinery to the commodities (b) to optimize the extraction of relative surplus value (c) to reduce costs of production, and prices of production to capture a greater portion of the total profit.

Technical progress has quite clearly caused companies to increase their level of output– in almost any industry you examine– as a matter of fact, companies pursue technical progress precisely to increase their levels of output– look at the history of semiconductor fabrication industry; flat screen TVs; cell phones; high traction locomotives; petroleum.

And as a consequence, crises of overproduction– which is not the same thing as underconsumption– is not driven by a dearth of demand, but the very same decline in profitability that is manifested in the tendency of the rate of profit to decline.

Again, look at, for example, the transformation of the semiconductor fabrication from a “value added” industry to what the business analysts like to call a “commodity” industry, with quite pronounced cycles of technical investment and expansion, increased “demand,” overproduction, declaring profitability, contraction.

Overproduction is quite clearly driven by the larger concentration of capitals– again look at petroleum in the 1990s, semiconductors, aircraft production, or most recently maritime transport construction.

And of all the things Engels has written, this:

“I am familiar with capitalist production as a social form, or an economic phase; capitalist private production being a phenomenon which in one form or another is encountered in that phase. What is capitalist private production? Production by separate entrepreneurs, which is increasingly becoming an exception. Capitalist production by joint-stock companies is no longer private production but production on behalf of many associated people. And when we pass on from joint-stock companies to trusts, which dominate and monopolise whole branches of industry, this puts an end not only to private production but also to planlessness.”

is just flat out wrong. Capitalist production is not defined as production of private entrepreneurs as opposed to joint stock companies. That’s a nonsense distinction so that what when BNSF was publicly traded, as are the NS, UP, CSX, CP railroads, it WASN’T capitalist production, conducted for the purposes of the accumulation of value, of private wealth? But when Buffet took it private, it became so?

Or any company that issues and IPO? Does it go from being capitalist to non-capitalist? Does it make any difference to the social relation of production, that is to say the organization of social labor, if it exists as a publicly held company or in KKR’s private equity portfolio?

The legal form of the company is not determinant of its existence as capital.

Boffy,

You paint a picture of investment going into finance/assets and away from ‘real’ production, but if you look at steel production, coal production they are at all time highs. So are you not missing from your analysis the fact that production has moved to the ‘East’ and that the ‘West’ is the finance centre of world capitalism, and must therefore be analysed in that way?

Not at all. In fact, that’s a pretty central aspect of my analysis, and why the North Atlantic crisis should be analysed as a financial crisis of the type Marx describes, rather than as an economic crisis.

As Marx and Engels point out, in the period up to the 1847 crisis, investment in the textile industry, which was by far the most important industry of the time was also at record levels.

But Engels comments,

“The new market gave a new impetus to the further expansion of an expanding industry, particularly the cotton industry… But all the newly erected factory buildings, steam-engines, and spinning and weaving machines did not suffice to absorb the surplus-value pouring in from Lancashire. With the same zeal as was shown in expanding production, people engaged in building railways. The thirst for speculation of manufacturers and merchants at first found gratification in this field.”

He goes on,

The enticingly high profits had led to far more extensive operations than justified by the available liquid resources. Yet there was credit-easy to obtain and cheap. The bank discount rate stood low: 1¾ to 2¾% in 1844, less than 3% until October 1845, rising to 5% for a while (February 1846), then dropping again to 3¼% in December 1846. The Bank of England had an unheard-of supply of gold in its vaults. All inland quotations were higher than ever before.”

http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1894-c3/ch25.htm

The comment,

“The enticingly high profits had led to far more extensive operations than justified by the available liquid resources.”

seems to contradict the following statement about the availability of cheap credit. But, in fact it illustrates an important element of Marx’s theory of a crisis of overproduction. The total social product as with any commodity itself is comprised of C + V + S. But, within the total social product, C is not purchased from revenue, it is an exchange of capital with Capital. If we consider the economy as just one single firm, it is as though this firm simply produces the constant capital it requires and uses it, without it ever going through its books, or through a process of exchange, rather like a coal mine simply uses its own coal to fuel the steam engines it uses to pump water from the mine. The coal it so uses, forms a part of the value of its end product, but it is not something it has paid money for to purchase. It is only V + S, which constitute revenue in the form of wages, profits, interest and rent (National Income), which is available to purchase the final product. However, a portion of S is used to accumulate additional productive capital, in the shape of constant capital. In a period of boom, and high profits, capitalists are encouraged to devote a greater proportion of S to this activity. But, to the extent they do so, the proportion they devote to the consumption of final production, i.e. of consumption goods falls. The consequence is that the production of capital expands, but a disproportion arises then with demand for the additional production of that capital. When Marx talks about “available liquid resources” here, he does not mean then the amount of actual money available in the system, but the amount of money in the form of revenue to form demand for final consumption.

In Theories of Surplus Value III, Marx quotes Ricardo,

“…I can only answer, that glut […] is synonymous with high profits…” (op. cit., p. 59).”

Marx comments,

“This is indeed the secret basis of glut.” (p 121)

In other words, as profits rise, capital is led to invest a greater proportion of it into additional productive-capital. The surplus value, S, besides its division into interest, profit and rent, is divided into a portion spent on consumption goods (s1), plus an amount spent on luxury goods (s2), and an amount advanced for accumulation (sa). To the extent that the latter is expanded, the other two must contract, even if only relatively as the total of s increases. But, the purpose of (sa) is only to produce additional commodities for final consumption, i.e. to produce consumption goods. The additional expenditure (sa), therefore results in an expanded volume of consumption goods, at a time when the capitalists own surplus value devoted to consumption spending is relatively diminished. If, the increase in the rate and mass of profit, is a result of a rising rate of surplus value, so that the proportion of national income accounted for by wages also falls relatively, then the volume and value of consumption goods, is being expanded, whilst the amount of revenue available to buy it (the “available liquid resources” in Marx’s words) is relatively diminished (again even if its total value is greater).

The value of each of these commodities for final consumption is likely to fall, but the total value of the mass of these use values dumped on the market will have risen. In order to clear all of them in the face of a relatively diminished quantity of revenue, the market price of each of these commodities, must, however, fall even below this level, so that the realised profit is squeezed. If the market price falls enough, it will fall below the cost of production of the commodity, so that the capital used in its production will not be reproduced. As Marx puts it,

“The entire mass of commodities, i.e. , the total product, including the portion which replaces the constant and variable capital, and that representing surplus-value, must be sold. If this is not done, or done only in part, or only at prices below the prices of production, the labourer has been indeed exploited, but his exploitation is not realised as such for the capitalist, and this can be bound up with a total or partial failure to realise the surplus-value pressed out of him, indeed even with the partial or total loss of the capital. The conditions of direct exploitation, and those of realising it, are not identical. They diverge not only in place and time, but also logically. The first are only limited by the productive power of society, the latter by the proportional relation of the various branches of production and the consumer power of society. But this last-named is not determined either by the absolute productive power, or by the absolute consumer power, but by the consumer power based on antagonistic conditions of distribution, which reduce the consumption of the bulk of society to a minimum varying within more or less narrow limits. It is furthermore restricted by the tendency to accumulate, the drive to expand capital and produce surplus-value on an extended scale.”(p 244)

This reminds me: you know where some of the highest levels of self employment and unregulated markets are found? At the bottom of third world countries. Look out world, here we come!

Robert what you think about this: “Mysticism and the Labour Theory of Value” in http://socialdemocracy21stcentury.blogspot.com/2014/05/mysticism-and-labour-theory-of-value.html

Boffy,

In response to your response at 5:28 a.m. Yor analysis on oligopolies and remarks of Marx and Engels do relate to the period 1880-1910, a highly monopolised capitalism behind tariff walls, the world Hilferding and Lenin tried to describe.

Something changed between then and now. If there is more international competition (with deregulation, privatization, flexibility) there is also an increased chance of overaccumulation between global corporations in specific sectors such as ICT and cars. For empirical information see David Mcnally, The Global Slump,

Your arguments help to explain why it is so difficult to get rid of their huge planned overcapacity, let us not forget the huge amount of money invested in this, a free market devaluation of this capacity risks an enormous crisis, also of their financial assets a lot of these huge car corporations do operate as if they were internationally operating banks, the problem of overaccumulation is real and very difficult to handle in modern time Global Capitalism.

Click to access FromFinancialCrisistoWorldSlump.pdf

I forgot to mention that the book of David Mcnally is published in 2010, his article with the same subject was published in 2009.

Henry,

Incidentally, I should point out that Engels comments cited above from his Critique of the Erfurt Programme are just a repetition of the analysis that Marx provides in Capital I and III, in relation to the “Expropriation of The Expropriators”, and the development of this socialised capital in place of the monopoly of private capital. So, Marx writes,

“The capital, which in itself rests on a social mode of production and presupposes a social concentration of means of production and labour-power, is here directly endowed with the form of social capital (capital of directly associated individuals) as distinct from private capital, and its undertakings assume the form of social undertakings as distinct from private undertakings. It is the abolition of capital as private property within the framework of capitalist production itself…

Transformation of the actually functioning capitalist into a mere manager, administrator of other people’s capital, and of the owner of capital into a mere owner, a mere money-capitalist. Even if the dividends which they receive include the interest and the profit of enterprise, i.e., the total profit (for the salary of the manager is, or should be, simply the wage of a specific type of skilled labour, whose price is regulated in the labour-market like that of any other labour), this total profit is henceforth received only in the form of interest, i.e., as mere compensation for owning capital that now is entirely divorced from the function in the actual process of reproduction, just as this function in the person of the manager is divorced from ownership of capital…

his result of the ultimate development of capitalist production is a necessary transitional phase towards the reconversion of capital into the property of producers, although no longer as the private property of the individual producers, but rather as the property of associated producers, as outright social property. On the other hand, the stock company is a transition toward the conversion of all functions in the reproduction process which still remain linked with capitalist property, into mere functions of associated producers, into social functions…

This is the abolition of the capitalist mode of production within the capitalist mode of production itself, and hence a self-dissolving contradiction, which prima facie represents a mere phase of transition to a new form of production. It manifests itself as such a contradiction in its effects. It establishes a monopoly in certain spheres and thereby requires state interference. It reproduces a new financial aristocracy, a new variety of parasites in the shape of promoters, speculators and simply nominal directors; a whole system of swindling and cheating by means of corporation promotion, stock issuance, and stock speculation. It is private production without the control of private property…

Aside from the stock-company business, which represents the abolition of capitalist private industry on the basis of the capitalist system itself and destroys private industry as it expands and invades new spheres of production, credit offers to the individual capitalist; or to one who is regarded a capitalist, absolute control within certain limits over the capital and property of others, and thereby over the labour of others…

The capitalist stock companies, as much as the co-operative factories, should be considered as transitional forms from the capitalist mode of production to the associated one, with the only distinction that the antagonism is resolved negatively in the one and positively in the other.”

A Final comment on this, because I have a lot of work to get through. In addition to Marx and Engels comments about the role of socialised capital and the way it changes the dynamic by introducing planning in place of market competition for these giant corporations. Simon Clarke summarised it succinctly in the Winter 1990 edition of Capital and Class. he wrote,

““Indeed it would be fair to say that the sphere of planning in capitalism is much more extensive than it is in the command economies of the soviet bloc. The scope and scale of planning in giant corporations like Ford, Toyota, GEC or ICI dwarfs that of most, if not all, of the Soviet Ministries. The extent of co-ordination through cartels, trade associations, national governments and international organisations makes Gosplan look like an amateur in the planning game. The scale of the information flows which underpin the stock control and ordering of a single Western retail chain are probably greater than those which support the entire Soviet planning system.”

Henry,

80% of the global car market is controlled by just 5 companies. As with many other such industries, its not just this centralisation of ownership and control that is important. Even outside it, there is widespread co-operation between corporations for the purpose of development and so on. That is not to mention the role that is played by large interventionist welfare states working in conjunction with these huge corporations.

The increased competition does not take the form of competition for market share based on price, which requires unlimited expansion of output, because competition for these huge corporations on the basis of price was found to be self-destructive. Instead competition is undertaken on the basis of continual improvement in quality, and choice.

There is a problem with barriers to exit. Back in 2010, some time before Kliman wrote, The Failure of Capitalist production, I wrote a blog – http://boffyblog.blogspot.co.uk/2010/11/momentous-change-part-1.html – referring to the work of Steindl in relation to the way the huge monopolies that existed in the 1930’s, acted to prevent capital moving to the most profitable areas. In so doing, it meant that after the period of stagnation, the rate of profit did not recover as quickly as it would have done had capital been reallocated to the more dynamic new areas.

I suggest this is true of the situation after the period of stagnation of the 1980’s and 90’s too. Its not a result of over accumulation, but of under accumulation in these new dynamic areas.

I am in the process of writing a number of books, which means my time is limited. But, one final point here that I will be covering is that, in fact, modern capitalism has found a solution to these rigidities in the transfer of physical capital. It revolves around Marx and Engels analysis of the change from private capitalism to the socialised capital of the Joint Stock Company, corporation etc. The average rate of profit theorised by Marx is calculated on the productive-capital, and relies on capital-value moving from low profit areas to high profit areas. In capital III, Marx recognises that this does not happen in respect of the large socialised capitals, which is one reason they do not participate in the calculation of average profit.

But, for capitalists, who as Marx points out are all transformed into money-capitalists, as share and bond owners, as opposed to capital, what becomes important is not the average profit that is derived from the productive-capital, but the average “profit” they can obtain from their share or bond ownership – with some adjustment for risk etc. similar to the “grounds for compensating” that Marx refers to in the determination of prices of production. For capitalists as opposed to capital, their investment is only what they advance to buy shares or bonds, and the “profit” they make is the total return, the yield plus capital gain obtained from that “investment”.

Its on this basis that their rate of profit is averaged via the continual, and almost instantaneous adjustment of capital values reflected in the market capitalisation of company shares and bonds, via the capital markets. Its no longer necessary on this basis, for capital to physically move immediately from one sphere to another to bring about such an average rate of profit, because the risk adjusted average return is effected for capitalists instead by the adjustment of capital values reflected in the share and bond prices.

Boffy,

Still a lot of quotes of Marx and so on, but no response to the article of Mcnally on Global Overacccumulation, Marx Capital lll is based on full market competition that is not the case in modern times, allthough deregulation of global financial markets increased competition, but i.e. the Chinese use capital controls to protect their markets and have a huge state owned financial sector. A kind of hierarchy of sectors and profit rates could be possible in the global economy, something Steindl mentioned but the global situation changed since the writings of Steindl, this must be empirically researched! The work of Carchedi on international oligopoly capitalism can be source of inspiration.

Well, just one question: If as some like to claim the tendency of the rate of profit is offset directly by an increase in the mass of profit, hence no critical impact is registered in its decline, and if capital because of its “cooperation” and “planning” of its largest capitals is no longer to general, systemic eruptions of overproduction, then exactly what is left of Marx’s immanent critique of capital– where capital becomes the barrier to the accumulation of capital; where the conflict between the growth in the means of and the relations of production, i.e. the social organization of labor, actually undermines the product of that social organization which is the accumulation of value?

Short answer: Nothing. All the problems are attributable to “mistakes” “short-sightedness” of (pick one) Austerians, Austrians, monetarists, or Keynesians if that’s your preference.

What we have here with this meta-theorizing is a form of cognitive dissonance, where what has actually occurred in capitalism since 2008, or between 2001 and 2008, or through its cycles since 1971– cycles that take place under a specific general decline in profitability– doesn’t matter, is ignored.

We get cargo-cult capitalism, where the planes are always flying, the goods are always delivered, to wit:

“Aside from the stock-company business, which represents the abolition of capitalist private industry on the basis of the capitalist system itself and destroys private industry as it expands and invades new spheres of production…”

Complete nonsense. This is not the “dissolving of capitalist production by capitalist production itself”– it’s the reproduction of capitalist production. Capitalist production does not dissolve itself; it undermines value accumulation, profitability, but that dissolution does not amount to a new social organization of labor. For that capital must be overthrown.

If you want to claim that Marx’s analysis of the evolution of socialised capital and his description of it as “the abolition of capitalist private industry on the basis of the capitalist system itself” is “Complete nonsense” you are free to do so.

But then why are you so bothered about the question,

“exactly what is left of Marx’s immanent critique of capital”. If you think Marx’s critique is “utter nonsense” anyway what would it matter what was left of it?

In reality, of course, you understand little of the analysis or the nuances, and are only interested in provoking argument.

No, I don’t think Marx’s critique is utter nonsense, since Marx’s analysis of capital in the Grundrisse, in Capital does not support your cherry-picking version, your disavowal of Marx’s effort to produce the immanent critique of capital, where the extraction of surplus value becomes the obstacle to the reproduction of capital, the realization of profit.

I think this notion of the abolition of capitalist private industry on the basis of capitalism is nonsense– it represents a “flight of fantasy” of Marx, or more accurately, Engels (like his notion of the law of value applying throughout history to pre-capitalist societies) and it ignores the opposing, conflicting actions that occur at precisely the same time– like those that occur in reality– LBO, private equity, privatization, asset liquidation etc… all the stuff you ignore on your (Kautskyesque) version of super-homogenized capitalism.

Look around Boffy, tell me exactly where DuPont, or General Motors, or Peugeot is different, in its appropriation of human labor than a private equity corporation like say….BNSF, RJ Reynolds etc. etc.

Cognitive dissonance indeed; you are the flying saucer cultist of capitalism.

Marx’s, and Engel’s “flights of fancy” are “excusable” in that there is a core to the Marx’s immanent critique of capital, that stands in opposition to the notions of self-dissolution of capital. Your flights of fantasy, depending on, as they do, distortion of actual economic data, and Marx’s real object, are not excusable– in that they lead nowhere but to a reconciliation with capital along this or that social-democratic model.

You’re the one who describes Marx’s analysis as “utter nonsense”. You’re the one who disavows Marx’s analysis of value as labour. You’re the one who disavows Marx’s definition of productivity.

Incidentally in the process your attempt to reconcile your failure to understand basic economic theory let alone Marxism in that regard led you to try your usual production of a load of meaningless verbiage and irrelevant quotes about the production of value. If you understood the difference between value and use value you would know that your argument was nonsense, because productivity can only ever be a measurement of the production of use values not values. The quantity of value produced in an hour by abstract labour can only ever be an hour!

You’re the one who disavows Engels analysis of the Law of Value, and his detailed account of how Marx arrives at its historical development. You’re the one who disavows Marx’s own historical development of value in Capital, and by ridiculously describing it as only being produced by wage labour undermines the whole of Marx’s theory of value and of money as the universal equivalent form of value. Given that Marx analyses the development of money as the ultimate form of the form of value, and given that he analyses the existence of money going back thousands of years, you must think his analysis of value and money is “utter nonsense too”, because that would mean that money as the universal equivalent form of value existed for thousands of years before value itself!

You are the one who disavows Marx’s comments in the Critique of the Gotha Programme, and in Capital about value continuing to be the basis of calculation and distribution under the first stage of Communism, as well as disavowing Marx’s definition of the Law of Value applying to all modes of production in his letter to Kugelmann, and his analysis of value on that basis in relation to Robinson Crusoe in Capital I.

You are the one who disavows Marx’s detailed analysis of the process of “the expropriation of the expropriators” in Capital, in his programme for the First International, and so on.

In fact, because you clearly do not understand Marx and Engels work, and merely Google for quotes to meet your immediate requirements for trolling you end up making silly mistakes that leave you at odds with basis elements of their analysis, which you then have to try to reconcile with the kind of gobbledegook you come out with that tries to sound profound, but which is just bollocks.

Its the same way you google for facts to try to support your arguments, which don’t, and the way you are forced to try to nit pick about the words others use, to try to make them seem to be saying something they are not, even when they repeatedly state that your definition of what they have said is not what they were saying.

But, of course, that is what you aim for, it is the meat and drink of a troll, endless pointless, ill tempered argument. Which is why I won’t argue you with you, but I’m happy to simply point out the ignorant, ludicrous comments you come out with.

When you quote Marx’s very clear comment,

““Aside from the stock-company business, which represents the abolition of capitalist private industry on the basis of the capitalist system itself and destroys private industry as it expands and invades new spheres of production…”

and then say,

“Complete nonsense”.

I’d say that was a pretty clear example of you disavowing Marx’s analysis, especially after that quote comes in a lengthy section of capital, in which in detail describes this process of transformation, which also links in with their analysis of that process elsewhere, and especially as it is a central aspect of the theory of historical materials of how new modes of production grow out of existing ones!

By the way the crap you write about DuPont etc. also simply shows that you do not underssand/have not bothered to read the comments made by Marx and Engels, because you would otherwise know that what you say has nothing to do with the argument that is being made!

I don’t buy into the idea that value has always existed, and more precisely certainly not value producing labour but I don’t think Engels was wrong to say that exchange value in the final analysis was always equated labour time. So I can see where Boffy is coming from.

I think the debate here is possibly mixing up capital and value and being too abstract about the historical processes (not precise enough). Money exists before money capital, Marx in the Grundrisse (consumption directed circulation):

“This motion can take place within peoples, or between peoples for whose production exchange value has by no means yet become the presupposition. The movement only seizes upon the surplus of their directly useful production, and proceeds only on its margin.”

This circulation can never realise capital:

“On the other side it is equally clear that the simple movement of exchange values, such as is present in pure circulation, can never realize capital. It can lead to the withdrawal and stockpiling of money, but as soon as money steps back into circulation, it dissolves itself in a series of exchange processes with commodities which are consumed, hence it is lost as soon as its purchasing power is exhausted.”

“For this reason the sophistry of the bourgeois economists, who embellish capital by reducing it in argument to pure exchange, has been countered by its inversion, the equally sophistical, but, in relation to them, legitimate demand that capital be really reduced to pure exchange, whereby it would disappear as a power and be destroyed, whether in the form of money or of the commodity”

As this process becomes embedded over time, then this form of exchange takes a qualitative leap, and here I think Sartesian is more correct than Boffy (who is too abstract or general in his opinions):

“This movement appears in different forms, not only historically, as leading towards value-producing labour, but also within the system of bourgeois production itself, i.e. production for exchange value. With semi-barbarian or completely barbarian peoples, there is at first interposition by trading peoples, or else tribes whose production is different by nature enter into contact and exchange their superfluous products. The former case is a more classical form. Let us therefore dwell on it. The exchange of the overflow is a traffic which posits exchange and exchange value. But it extends only to the overflow and plays an accessory role to production itself. But if the trading peoples who solicit exchange appear repeatedly (the Lombards, Normans etc. play this role towards nearly all European peoples), and if an ongoing commerce develops, although the producing people still engages only in so-calledpassive trade, since the impulse for the activity of positing exchange values comes from the outside and not from the inner structure of its production, then the surplus of production must no longer be something accidental, occasionally present, but must be constantly repeated; and in this way domestic production itself takes on a tendency towards circulation, towards the positing of exchange values. At first the effect is of a more physical kind. The sphere of needs is expanded; the aim is the satisfaction of the new needs, and hence greater regularity and an increase of production. The organization of domestic production itself is already modified by circulation and exchange value; but it has not yet been completely invaded by them, either over the surface or in depth. This is what is called the civilizing influence of external trade. The degree to which the movement towards the establishment of exchange value then attacks the whole of production depends partly on the intensity of this external influence, and partly on the degree of development attained by the elements of domestic production — division of labour etc. In England, for example, the import of Netherlands commodities in the sixteenth century and at the beginning of the seventeenth century gave to the surplus of wool which England had to provide in exchange, an essential, decisive role. In order then to produce more wool, cultivated land was transformed into sheep-walks, the system of small tenant-farmers was broken up etc., clearing of estates took place etc. Agriculture thus lost the character of labour for use value, and the exchange of its overflow lost the character of relative indifference in respect to the inner construction of production. At certain points, agriculture itself became purely determined by circulation, transformed into production for exchange value. Not only was the mode of production altered thereby, but also all the old relations of population and of production, the economic relations which corresponded to it, were dissolved. Thus, here was a circulation which presupposed a production in which only the overflow was created as exchange value; but it turned into a production which took place only in connection with circulation, a production which posited exchange values as its exclusive content.”

Boffy, half cargo-cultist half rubber-band man, makes a lot of accusations rather than answer any of the concrete questions that are posed.

Like the argument that output is determined by “demand” and technical progress is not the driver of output; or the nonsense about a joint stock company– so tell us was RJ Reynolds a non-capitalist corporation when publicly traded, morphing into a capitalist one when taken private? Tell us exactly how the relations between classes changes; how the organization of wage-labor is altered?

Boffy won’t do that because he can’t do that.

He argues about value being an eternal form, quoting exactly that letter where Marx explicitly shows that value, the production of a commodity as a value is a specific historical form.

My argument by the way is not that value doesn’t precede capitalism; but that the production of and for value, for the accumulation of value, the law of value, is a relation of classes, of labor, and cannot regulate the distribution of social labor time separate and apart from those classes.

Simple question: does wage-labor exist after the overthrow of capitalism and the expansion of socialism? Well, its’ not supposed to, and if there is no wage-labor exactly what is the basis for “value”– as opposed to use-value, as opposed to the “free association of producers.” Exactly how does “value” a product of the alienation of labor, survive the end to that alienation (I use alienation here in its “commercial” sense)?

Boffy will go on and on about how much he understand, how much better he understands Marx, what Marx means, when it has already been demonstrated how little he understands of Marx’s analysis of the fall in the rate of profit AND that that decline is not automatically, inherently, necessarily, nor even likely offset by an increase in the mass of profits; and that in the accumulation of capital, the mass of profits cannot, over the long term, compensate for the decline in the rate as threshold costs increase.

He pretends Marx argues that large capitalists will economize on constant capital costs as opposed to labor costs, in direct contradistinction to the very reason Marx shows drives capitalist to increase constant capital, and the fixed asset portion, to replace labor.

He can do all these things because Boffy is the perfect liberal– that is liberal as Hegel defined it– a philosophy of the abstract that capitulates before the world of the concrete.

All I ask is for Boffy to demonstrate, in the concrete, where the joint-stock company has amounted to a dissolution of capitalism within capitalism (sounds a lot to me like Lenin claiming socialism was state capitalism being run for the benefit of all– an oxymoron, and a disavowal of the class content of each).

I ask Boffy to demonstrate where capitalism has economized on constant capital, since 1971, without a coincident attack on “V.”

I ask him to explain, concretely, the trends in the semiconductor, or petroleum, etc. industries that demonstrate his argument that in fact technical progress does not drive output, in volume and value.

And while he’s busy demonstrating those things in the concrete, I’d ask him to demonstrate the trade surplus the EU supposedly runs with China; the “Bric-like” growth of “some countries” in the Eurozone, and of course Sweden’s use of the euro.

And I just love how Boffy loves to claim how things have changed since Marx’s critique– how the move to monopoly, joint-stock companies, whatever Boffy can find, represent new determinants of capital, somehow not susceptible to what Marx analyzed as inherent, essential, conflicts that make-up capital, BUT despite all that change– all those things Marx wrote about financial crisis, commercial crisis, the program of the 1st International still apply as if this were 1848, or 1857, or 1868.

Edgar,

Marx is quite clear that Value is Labour, in fact in Capital III, he says precisely that “Value is labour.” And likewise, Labour which produces use value, is also value. Marx makes clear that the first form of this value, of these use values is as “products”, as opposed to commodities. He then describes the historical process by which primitive communities begin to exchange these “products” usually as part of wedding ceremonies. The basis on which these exchanges take place he says is at first haphazard, because the value inherent in these products does not initially take the form of exchange value. These communities exchange products which they have in surplus because they have some specific advantage in their production.

In Capital III, he describes the way it is in fact the role of merchants that brings about the transformation of these products into commodities, and the way to use his terms in Capital I, the value becomes stamped on the face of the commodity as its exchange value. It does this, because merchants take the multiple of products produced by these various communities, and the merchant has every reason to buy low and to sell high. They buy products produced by commodities that use less labour-time for their production, and sell them to communities that require a ,lot of labour-time for the production of those commodities. In this way products become transformed into commodities, and their value assumes the form of exchange value, first as the representative form of value, then the equivalent form of value, and finally as money as the universal equivalent form of value.

This, as Marx and Engels points out arises thousands of years ago, long before the existence of wage labour!

In his letter to Kugelmann, Marx describes PRECISELY what his theory of value, and of the Law of Value amounts to. He writes,

““Every child knows that any nation that stopped working, not for a year, but let us say, just for a few weeks, would perish. And every child knows, too, that the amounts of products corresponding to the differing amounts of needs demand differing and quantitatively determined amounts of society’s aggregate labour. It is self-evident that this necessity of the distribution of social labour in specific proportions is certainly not abolished by the specific form of social production; it can only change its form of manifestation. Natural laws cannot be abolished at all. The only thing that can change, under historically differing conditions, is the form in which those laws assert themselves. And the form in which this proportional distribution of labour asserts itself in a state of society in which the interconnection of social labour expresses itself as the private exchange of the individual products of labour, is precisely the exchange value of these products.”

In Capital I, Marx uses this same definition of value to explain that other definitions of it amount to commodity fetishism. In other words, in any society value is labour, the quantity of value is the quantity of expended abstract labour, and what appear as exchanges of things – whether they be products exchanged by primitive tribes, commodities exchanged by peasant communities, and individual direct peasant and artisan producers, or commodities produced by capitalist firms or even by a communist society, are nothing more in reality but an exchange of equal amounts of abstract labour-time.

Describing Robinson Crusoe’s individual production for his own consumption, Marx concludes,

“All the relations between Robinson and the objects that form this wealth of his own creation, are here so simple and clear as to be intelligible without exertion, even to Mr. Sedley Taylor. And yet those relations contain all that is essential to the determination of value.”

In the same section he describes the production of value on the same basis by the individual peasant family and the distribution of labour-power within it.

In Capital I, Marx writes, that Philosophers had been trying to understand the concept of Value for 2000 years. Hardly possible if value only arises under wage labour!

In Capital III, in discussing the process by which exchange values are transformed into prices of production, Marx again deals with the historical evolution of value and exchange value, by looking at the classic form of exchange value under petty commodity production – in fact most of his analysis of exchange value in Capital I is undertaken on the basis of exchanges at values, which is the situation that historical and logically exists under petty commodity production prior to capitalist production.

In this section, Marx makes precisely this point that to understand this you have to assume that production is undertaken by producers who still own their own means of production. On that basis they seek to recover the value of the constant capital (means of production) expended plus the value of the labour they have expended, on the basis of a common rate of surplus value.

He makes the point that this demonstrates the point made previously that commodities develop out of products exchanged by primitive communities.

But, he also makes the point, which is what Engels is referring to, that as soon as any capitalist production begins, the “Law of Value”, i.e. here meaning the exchange of commodities on the basis of exchange value, ceases. That as Engels says is around the 15th century. The reason Marx explains is because capitalist producers engage in production in search of profits. If its possible to make higher profits in one area – say cotton spinning – than any others, then capital will continue to invade that production until that is no longer true. But, that means that the supply of cotton yarn will continue to rise, pushing down the market price of yarn below its exchange value, until only an amount of profit can be made that is no more than can be made in say wool spinning.

But, because even peasant weavers buy spun cotton from capitalist producers, their input prices are no longer determined by exchange value. They are determined by the price of production determined by capitalist producers of yarn. These prices of production then become the cost prices of the peasant weavers, so that even if they only add the value of their labour to that cost, the market price of their own output is no longer purely the exchange value of the woven cloth. So, Marx writes,

“The foregoing statements have at any rate modified the original assumption concerning the determination of the cost-price of commodities. We had originally assumed that the cost-price of a commodity equalled the value of the commodities consumed in its production. But for the buyer the price of production of a specific commodity is its cost-price, and may thus pass as cost-price into the prices of other commodities. Since the price of production may differ from the value of a commodity, it follows that the cost-price of a commodity containing this price of production of another commodity may also stand above or below that portion of its total value derived from the value of the means of production consumed by it. It is necessary to remember this modified significance of the cost-price, and to bear in mind that there is always the possibility of an error if the cost-price of a commodity in any particular sphere is identified with the value of the means of production consumed by it.”

Later Marx sets out that the consequence of this is that those commodities that previously were considered to be produced by the average composition of capital may no longer be so, because the value of the constant capital and variable capital used in their production when measured by price of production, will be different than when measured according to exchange value. And, in fact, he says that this must also affect the calculated rate of profit too, because if the value of wage goods is higher measured by price of production than by exchange value, then workers will have to work a larger proportion of the day to reproduce their labour-power, which means the rate of surplus value must fall, causing the rate of profit also then to be lower. he writes,

“It is therefore possible that even the cost-price of commodities produced by capitals of average composition may differ from the sum of the values of the elements which make up this component of their price of production. Suppose, the average composition is 80c + 20v. Now, it is possible that in the actual capitals of this composition 80c may be greater or smaller than the value of c, i.e., the constant capital, because this c may be made up of commodities whose price of production differs from their value. In the same way, 20v might diverge from its value if the consumption of the wage includes commodities whose price of production diverges from their value; in which case the labourer would work a longer, or shorter, time to buy them back (to replace them) and would thus perform more, or less, necessary labour than would be required if the price of production of such necessities of life coincided with their value.”

Its on this basis that he and Engels say that commodities do not exchange at their exchange values, but the Law of Value, as it applies to all societies continues to function as the means by which social labour-time is allocated. And marx makes clear that this applies to the first stage of Communist society too.

In Capital III, Marx writes,

““Secondly, after the abolition of the capitalist mode of production, but still retaining social production, the determination of value continues to prevail in the sense that the regulation of labour-time and the distribution of social labour among the various production groups, ultimately the book-keeping encompassing all this, become more essential than ever.”

In the Critique of the Gotha Programme he says the same thing. He writes,

“Here, obviously, the same principle prevails as that which regulates the exchange of commodities, as far as this is exchange of equal values. Content and form are changed, because under the altered circumstances no one can give anything except his labor, and because, on the other hand, nothing can pass to the ownership of individuals, except individual means of consumption. But as far as the distribution of the latter among the individual producers is concerned, the same principle prevails as in the exchange of commodity equivalents: a given amount of labor in one form is exchanged for an equal amount of labor in another form.”

Engels makes the same point in Anti-Duhring, which was essentially co-written by Marx,

“The useful effects of the various articles of consumption, compared with one another and with the quantities of labour required for their production, will in the end determine the plan.”

And,

“As long ago as 1844 I stated that the above-mentioned balancing of useful effects and expenditure of labour on making decisions concerning production was all that would be left, in a communist society, of the politico-economic concept of value. (Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher, p. 95) The scientific justification for this statement, however, as can be seen, was made possible only by Marx’s Capital.”

I think you have to jump through far too many hopes to deny that weight of evidence of actual statements in carefully thought out theoretical works by Marx and Engels, not just in one place but in several, to deny that Marx’s concept of value is one that is solely specific to commodity production, let alone wage labour!

“Like the argument that output is determined by “demand” and technical progress is not the driver of output; or the nonsense about a joint stock company– so tell us was RJ Reynolds a non-capitalist corporation when publicly traded, morphing into a capitalist one when taken private? Tell us exactly how the relations between classes changes; how the organization of wage-labor is altered?

Boffy won’t do that because he can’t do that.”

No, I won’t do it for two reasons. Firstly, there is no point simply feeding trolls appetite for pointless discussion. Secondly, if you actually read the quotes given or had any kind of understanding of what they meant you would know that they have nothing to do with what you are trying to claim they mean!

If you can’t even read Marx’s quotes and take the time to try to understand them I certainly don’t have any interest debating your faulty understanding of them. I’d suggest you spend more time reading Marx rather than engaging in pointless debates. Oh you won’t do that, of course, because your a troll!

“My argument by the way is not that value doesn’t precede capitalism; ”

That was precisely what you claimed, arguing that it was only produced by wage labour.

Correction.

In the above post (1.22) last para should read “claim” rather than “deny”.

As the actual original discussion has typically been sidetracked by Artesians usual trolling the importance of Marx and Engels comments in relation to Michael’s original comments and investment is described in these quotes from Marx.

“With the progress of capitalist production, which goes hand in hand with accelerated accumulation, a portion of capital is calculated and applied only as interest-bearing capital… in the sense that these capitals, although invested in large productive enterprises, yield only large or small amounts of interest, so-called dividends, after all costs have been deducted.”

“The law that a fall in the rate of profit due to the development of productiveness is accompanied by an increase in the mass of profit, also expresses itself in the fact that a fall in the price of commodities produced by a capital is accompanied by a relative increase of the masses of profit contained in them and realised by their sale.”

“Under competition, the increasing minimum of capital required with the increase in productivity for the successful operation of an independent industrial establishment, assumes the following aspect: As soon as the new, more expensive equipment has become universally established, smaller capitals are henceforth excluded from this industry. Smaller capitals can carry on independently in the various spheres of industry only in the infancy of mechanical inventions. Very large undertakings, such as railways, on the other hand, which have an unusually high proportion of constant capital, do not yield the average rate of profit, but only a portion of it, only an interest. Otherwise the general rate of profit would have fallen still lower. But this offers direct employment to large concentrations of capital in the form of stocks.”

“The so-called plethora of capital always applies essentially to a plethora of the capital for which the fall in the rate of profit is not compensated through the mass of profit — this is always true of newly developing fresh offshoots of capital — or to a plethora which places capitals incapable of action on their own at the disposal of the managers of large enterprises in the form of credit.”

“The rate of profit, i.e., the relative increment of capital, is above all important to all new offshoots of capital seeking to find an independent place for themselves. And as soon as formation of capital were to fall into the hands of a few established big capitals, for which the mass of profit compensates for the falling rate of profit, the vital flame of production would be altogether extinguished. It would die out.”